1. Background

Congenital microgastria (CM) is an extremely rare anomaly due to impaired foregut development, which is characterized by a hypoplastic tubular stomach with abnormal function and mega esophagus. CM can cause gastroesophageal reflux disorder (GERD), vomiting, and failure to thrive. The first case of CM was reported in 1842 and recent studies revealed approximately 60 reported cases. This anomaly is often associated with other anomalies such as asplenia and renal, cardiac, and skeletal anomalies (1-4).

2. Case Presentation

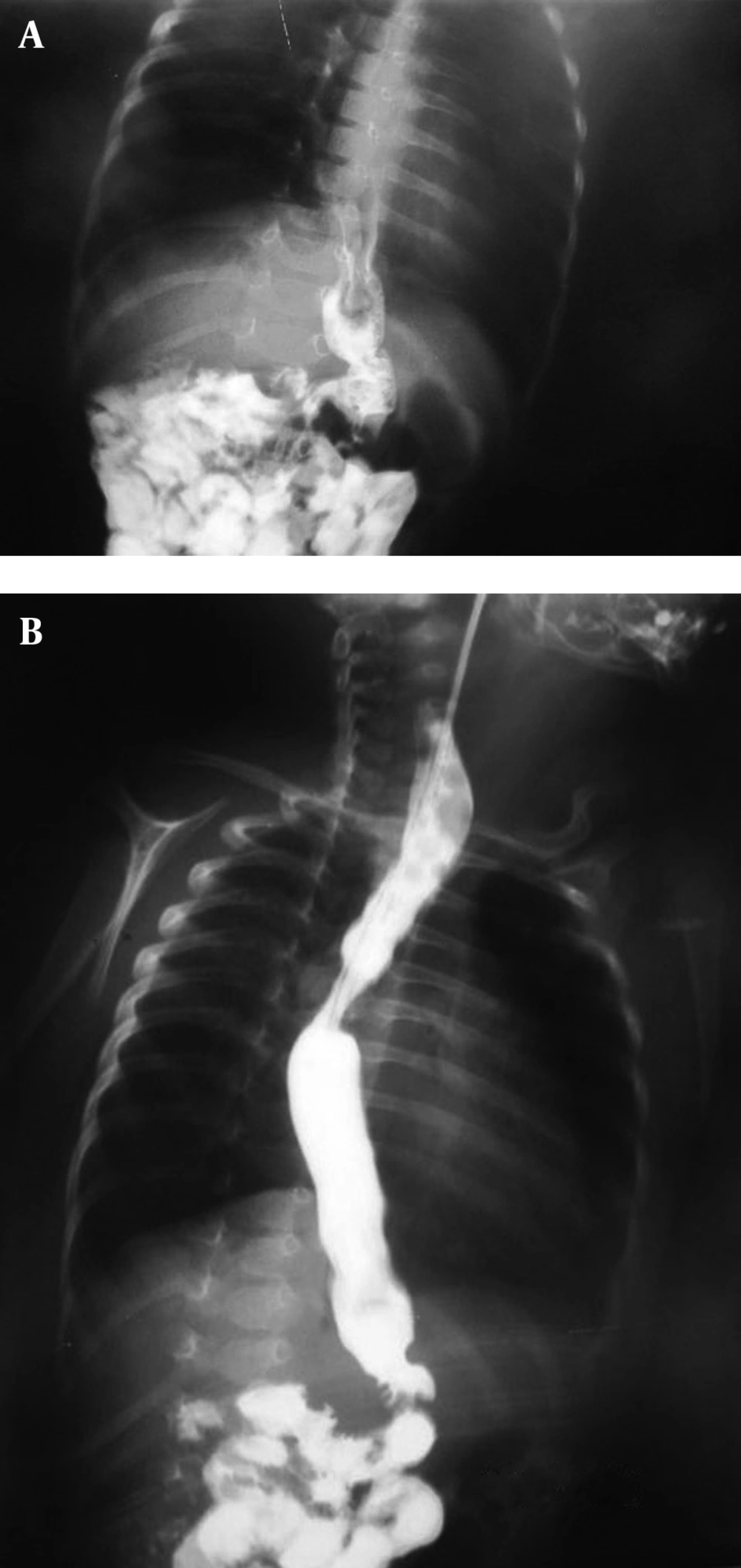

The patient was a two-month-old boy who was born from a 26-year-old primigravida mother after an uncomplicated pregnancy at term via vaginal delivery. His birth weight was 3 kg. At birth, he had meconium aspiration, cyanosis, and respiratory distress. Therefore, he was admitted to NICU for 13 days without special diagnostic evaluation. After discharge from hospital, he had projectile vomiting, cyanosis, and cough during feeding. On admission at six weeks of age, he was malnourished and dehydrated. He had tachypnea with supracostal and intercostal retraction, bilateral coarse rales, and expiratory wheezing; moreover, his skin was pale. He also had mild micrognathia, upper left limb hypoplasia (Figure 1), and flat abdomen. C-reactive protein, hematologic, and biochemical values were within normal limits. However, arterial blood gas was abnormal and indicated hypoxia and metabolic alkalosis (pH, 7.43; PCO2, 53 mm Hg; PO2, 72 mm Hg; and HCO3-, 34.8 mmol/L). Ultrasonography of the abdomen demonstrated normal findings regarding spleen, liver, and kidneys. Findings of brain computed tomographic scan were normal. An upper gastrointestinal (GI) contrast studies showed GERD, moderate dilation of esophagus with increased thickness of mucosa suggesting inflammatory changes (esophagitis), and a small-sized stomach that was vertically positioned at midline, suggesting microgastria (Figure 2).

Bronchoscopy revealed tracheomalacia. The patient was discharged on the 10th day of admission because of the parents’ unwillingness for further management. We instructed the parents to employ nasogastric feeding, small frequent meals, appropriate positioning, and prokinetic medications.

3. Discussion

CM is an extremely rare anomaly and occurs due to an arrest of gastric development from foregut during embryogenesis, which results in a small tubular or saccular stomach. This theory is supported by macroscopic developmental failure of the fundus, corpus, and antrum. A dilated poorly peristaltic esophagus and GERD are frequently evident. Dilatation of esophagus is due to compensation of microgastria and hence, it returns to normal size after surgery (5). These patients have inadequate food consumption and GERD. Therefore, nutrition is compromised and malnutrition, failure to thrive, and growth retardation are very common.

Associated GERD can cause aspiration pneumonia. CM is seldom an isolated abnormality and is usually associated with other anomalies. In a literature review, only two out of 39 microgastria cases were identified as an isolated anomaly (6).

Associated anomalies include intestinal malrotation, duodenal atresia, imperforate anus, transverse liver, asplenia, trachea esophageal anomalies, atrioventricular septal defects, renal dysplasia or aplasia, upper limb and spinal deformities, corpus callosum agenesis, micrognathia, and anophthalmia. Microgastria should be excluded in patients with midline defect and VACTERL association (vertebral, anal, cardiac, tracheal, esophageal, renal, and limb anomalies) (7-9). The diagnosis is usually made by an upper GI contrast study, with finding of a small, tubular stomach in an abnormal, usually in midline position (10, 11). Several histopathologic studies have shown normal gastric mucosa in microgastria; however the total gastric cell mass is significantly decreased, which causes reduced production of acid and intrinsic factor (12).

The treatment of microgastria must be individualized with conservative treatment for less severe forms and operation for severe forms. Conservative treatments include continuous nasoenteral or nasogastric feeds, small frequent meals, positioning precautions, and prokinetic medications. Gastrostomy and jejunostomy tubes may help in feeding; however, in conservative treatment, the stomach usually fails to enlarge and the growth of most patients is below the normal range (13-15). Because of persistent vomiting and recurrent pneumonia, which are the major problems in congenital microgastria, most patients require surgical intervention. Gastric augmentation to create a large gastric reservoir by double lumen Roux-en-Y jejunal (Hunt-Lawrence) pouch has had the best outcomes (1, 3). Given that most cases of congenital microgastria are associated with other anomalies such as VACTERL, we concluded that upper GI contrast studies should be done in patients with frequent vomiting and other accompanying anomalies.