1. Background

Childhood is an evolutionary stage in which the importance of the mutual emotional bond between the child and his/her career, especially the parents, is recognized for the physical, psychological and social development of the child (1). The adolescence period is also a transitional period between childhood and adulthood (2). Psychologists call it the emotional period, constructive cries, pressure period (3). Adolescence starts around the age of 12 - 13 and lasts until the age of 18 (4). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), adolescence is between the ages of 10 - 19. About one-fifth of the world’s population is made up of teenagers. The population of adolescents is reported to be 23% in less developed countries, 19% in developing countries, and 12% in the industrial countries (5). Meanwhile, this process is associated with rapid physiological changes, increased imbalance, and instability of mood. These changes can help the normal growth of the adolescent, but can also lead to behavioral, cognitive, and emotional problems (6). One of the current critical issues is the establishment of a healthy physical and social environment for children and adolescents because factors that disturb their living environment will also affect their health (7). Therefore, societies should provide the appropriate environment for care, education, and socialization of children and adolescents (8). Among the different social institutions, the family is known as the place to meet various physical, intellectual, and emotional needs (9), and it is also one of the effective factors in the upbringing of children of different ages, especially in childhood and adolescence (10).

Parental support is effective in maintaining health and improving children’s quality of life. The deprivation experienced by adolescents who have lost their parents leads to an increase in the prevalence of mental or behavioral disorders and a tendency to engage in anti-social activities (11). These children are placed in children’s homes (12). Studies show that the number of children living in residential care is increasing every year. This number has tripled since the 1980s. Current numbers show that more than 530,000 children live in residential care in the United States (13) and increased substantially to 500,000 (14). During recent years, the number of these children is increasing in Iran (15).

Life, aside from the family in the long-term, puts these children and adolescents to the lack of meaningful familial communication, personal and social problems, reduced happiness, sadness, and general loss of quality of life. Despite the provision of material facilities, these centers do not adequately meet the psychological needs of children and are shown to have a weaker performance in children’s physical and mental development than that of the family. Emotional communications within the family are more dynamic and stable (11). Considering the demographic structure of Iran and its population of young people, attention to improving the quality of life of Iranian adolescents is of particular importance because one of the variables influenced by the lack of parental care is the quality of life (16). The WHO defines the quality of life as the perception of a person from his/her present situation, with regard to the culture and value system in which he/she lives, and the relationship of these findings to the goals, expectations, standards, and priorities of each person (17).

On the other hand, Happiness, which is an essential dimension of life and related to functioning and success (18). In a study, quality of life as an approach that increases happiness (19). Happiness or psychological and mental well-being is a positive value that a person gives himself, and it expresses emotional experience, happiness, personal satisfaction, and satisfaction from different parts of life (20).

Researchers in a study showed that symptoms of anxiety in children and adolescents living in residential care are higher than those who live with their parents (21). While in a study reported the quality of life of children and adolescents in residential care was lower than those living in parental care (22). According to another study, to investigate the effectiveness of a group therapy reality approach to increasing happiness and improving the quality of life of poorly supervised adolescents. It showed that group therapy reality has been effective in improving the quality of life, increasing happiness, and satisfying the life of adolescents who were poorly supervised (23). Considering the importance of adolescence and quality of life during this period, and because quantitative factors are related to the quality of life and the happiness in individuals, the evaluation of quality of life and happiness is important in children and adolescents in residential care compared with other children and adolescents (11).

2. Objectives

Because insufficient information is found regarding this issue; therefore, the researchers aimed to compare the quality of life and happiness in children and adolescents in residential care and those in parental care.

3. Methods

This is a descriptive-analytic study conducted from April to January 2015 with the aim of comparing the quality of life and happiness in adolescents and children in residential care and those in parental care in Ahvaz. The research samples consisted of 75 children and adolescents aged 8 - 18 who had been residing in residential care for more than one year and 75 children and adolescents who are in parental care and chosen through the random multi-stage approach, among those who were admitted to secondary and high schools in Ahvaz after explaining the objectives of the study to eligible cases, the written informed consent was obtained from parental in parental care group and orphanage authorities’ in residential care group.

The inclusion criteria were living more than a year in an orphanage, orphanage authorities’ consent, living in residential care group and with both parents, parental consent in parental care group and between the ages of 8 and 18 years, the child and adolescent willingness to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were mental retardation, and chronic physical illness in children and adolescent participants unwilling to take part in or to continue in the study were excluded from the results in both groups. The data collection tool consisted of a questionnaire for demographic information based on the Kid Screen Quality of Life and the Oxford Happiness questionnaires. The Kid Screen questionnaire was used to evaluate the quality of life, which included 5 categories. These categories included a physical element to measure the levels of physical activity, energy and fitness. The psychological category to evaluate positive emotions, satisfaction of life, and balanced feelings. The social dimension to evaluate relationships with parents, autonomy, the home environment, amounts of freedom associated with age, degrees of financial resources, and satisfaction. The category of social support and peers to examine relationships with peers. Finally, the school environment category to examine the levels of adolescent perception of cognitive capacity, learning, concentration, and feelings about school. This tool shows the frequency of behavior of a particular feeling or intensity of an attitude (12). In the research of Ravens-Sieberer et al. (24), the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were ranged from 0.77 to 0.89. The Oxford Happiness questionnaire of 29 questions was developed to investigate happiness. Hills obtained an alpha coefficient of 90% (25). Najafi et al. (26) reported that the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and retest reliability coefficient were 90% and 79% in the total sample, respectively.

3.1. Statistical Analysis

Data after collection were analyzed by SPSS software (version 20). Inferential statistics, Independent t-test, Pearson correlation coefficient, Spearman, and Chi-square were used to compare the differences between the groups. P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The current study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Khorasgan Branch of Islamic Azad University (ethical code: 494011).

4. Results

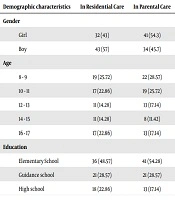

The study used information about 150 children and adolescents in two groups. Those in residential care and those in parental care (each group contained 75 individuals). The mean age of the girls in the parental care category was 11.82 ± 2.77 years and the mean age of girls in residential care was 11.97 ± 3.29. Data distribution was reported normal using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (P > 0.05). There was no significant relationship between age with happiness and quality of life (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference between girls and boys regarding their quality of life and happiness in any of the groups (P < 0.05) (Table 1). The lack of happiness was observed in (25%) 20 samples in the parental care and (37%) 28 samples in the residential care group. However, results showed a significant difference in happiness between the groups. Happiness in the parental care group was higher than the residential care group (P = 0.017). There was a statistically significant difference between the quality of life in both groups. The quality of life in the parental care group was better than the residential care group (P < 0.001). There was a significant statistical difference between the other dimensions of quality of life in both groups (P = 0.01). There was a direct and significant relationship between the quality of life and happiness in both groups (P = 0.001, P = 0.504, P = 0.001, P = 0.65) (Table 2).

| Demographic characteristics | In Residential Care | In Parental Care |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Girl | 32 (43) | 41 (54.3) |

| Boy | 43 (57) | 34 (45.7) |

| Age | ||

| 8 - 9 | 19 (25.72) | 22 (28.57) |

| 10 - 11 | 17 (22.86) | 19 (25.72) |

| 12 - 13 | 11 (14.28) | 13 (17.14) |

| 14 - 15 | 11 (14.28) | 8 (11.42) |

| 16 - 17 | 17 (22.86) | 13 (17.14) |

| Education | ||

| Elementary School | 36 (48.57) | 41 (54.28) |

| Guidance school | 21 (28.57) | 21 (28.57) |

| High school | 18 (22.86) | 13 (17.14) |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

| Quality of Life Dimensions | Numbers | Values | P Value | t-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical health | < 0.001 | 5.17b | ||

| In parental care | 75 | 21.85 ± 2.62 | ||

| In residential care | 75 | 17.51 ± 3.30 | ||

| Emotions | 0.004 | 2.97 | ||

| In parental care | 75 | 24.51 ± 2.53 | ||

| In residential care | 75 | 22.8 ± 2.28 | ||

| Family and leisure | < 0.001 | 14.76 | ||

| In parental care | 75 | 24.68 ± 4.07 | ||

| In residential care | 75 | 12.71 ± 2.53 | ||

| Friends | < 0.001 | 3.73 | ||

| In parental care | 75 | 16.08 ± 2.21 | ||

| In residential care | 75 | 13.68 ± 3.08 | ||

| School and learning | < 0.001 | 4.95 | ||

| In parental care | 75 | 17.5 ± 2.54 | ||

| In residential care | 75 | 14.08 ± 3.20 | ||

| Quality of life total | < 0.001 | 10.70 | ||

| In parental care | 75 | 104.00 ± 9.04 | ||

| In residential care | 75 | 80.80 ± 9.08 | ||

| Happiness | 0.017 | 2.43 | ||

| In parental care | 75 | 54.51 ± 16.19 | ||

| In residential care | 75 | 45.14 ± 15.99 |

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD.

bP is used for quantitative data from an independent t-test and qualitative data from chi-square.

5. Discussion

The findings of the present study show that the mean total score in the quality of life category for the residential care group is lower than the parental care group. Studies that examined academic self-effective, adaptability, and the quality of life between the girls in residential care and the girls in parental care have shown that the quality of life of ordinary students was higher than that of the orphanage’s students (27, 28). This is consistent with the results of this study.

In the present study, the mean scores of happiness in children and adolescents in residential care were lower than those in parental care. The results of a study indicated that the level of happiness in orphanage children was lower than other children (29). According to a study concluded, the home environment for children and adolescents leads to increasing the happiness of children and adolescents (23).

The physical and psychological activity dimension of children and adolescents in residential care is lower than those in parental care. This is consistent with the results of the Loman study (30). Studies show that youth in the institutional care sample reported higher scores on somatic complaints, and institutionalized children had consistently higher rates of externalizing behaviors such as conducting problems and internalizing behaviors such as emotional and peer problems compared to children from the community sample. This is consistent with the results of the present study (31). Researchers in a study reported that the prevalence of mental disorders is 13.3% among youth from age 9 - 16 years (32).

In the present study, the mean score of quality of life in the emotion and mood dimension in the group of children living in residential care was lower than the parental care group. The prevalence of problem behaviors ranged between 18.3% - 47% among those in institutional care versus 9% - 11% among the national sample (33). In this regard, a researcher showed that mental health was lower in residential care adolescents (34). A study was done in Stockholm (Sweden) reported that the prevalence of mood disorders in children at the age of 18 who were living in residential care for a long time was more than children who were either only in residential care short term or in care at younger ages (35). This is consistent with the results of the present study.

The next category of the quality of life was of the family and leisure time. This related to how the young person communicates with family, friends, colleagues, and the community. In the present study, the mean score of the quality of life in the group who lives in residential care about their families, friends, and school life is shown to be less than those living at home. Researchers in a study reported that the communication model based on the family’s conversations of high school students is predictive of their quality of life (36). This is consistent with the results of the present study.

According to a study, communication skills did not show significant differences between adolescents in residential care and adolescents in parental care. This is not consistent with the results of the present study. From the viewpoint of the researchers, this is because, despite the injuries of childhood, the orphanage’s adolescents are living in a group environment in which communication skills and abilities are considered to be very important. Additionally, in this orphanage’s environment, educational classes and workshops for children and adolescents are a regular feature (37). A researcher investigated the environmental and psychological predictors of academic success of students ages 9 - 14 years in Ankara, and reported that the youth were living away from their families were the most disadvantaged among in behavior problems, social support, and school adjustment (38).

The mean score of quality of life in the category of the school and learning for children in residential care is lower than the children in parental care. The result of a study showed that the students in parental care had more academic self-effective and talent flourishing than of the students in residential care. It can be said that various factors such as lack of family, peer pressure, and stress based on ability will likely affect the reduction of academic self-effective of the students in residential care (27).

Therefore, children who are in orphanages due to the lack of stable family life, also lack being able to express their emotions, doing subsequently lose happiness and consequently, their quality of life reduces. This remains consistent with the results of this particular study. Therefore, it may be concluded from the results of this study that children and adolescents deprived of stable family life also deny many useful experiences and learning opportunities, which often leads them to negative behavioral patterns. This study showed that the quality of life and happiness in children and adolescents in Ahvaz’s residential care was lower than for children and adolescents in parental care. Therefore, the children in residential care, as a vulnerable group, require special attention for their development and growth. Therefore, careful attention needs to be given to the quality of life and happiness as a key factor for useful and effective future planning about the lives of children and adolescents in residential care.

5.1. Research Limitations

One of the constraints of this study is the dependence of information presentation on memory and self-report in individuals. In future studies can be based on observation of behavior information obtained.

5.2. Conclusions

The results of this study showed that children and adolescents in residential care had lower quality of life and happiness than children and adolescents in parental care.