1. Background

Neonatal acquired in utero, and perinatal infections are important to mortality and future growth and development of the neonates (1). Toxoplasmosis, Others, Rubella, Cytomegalovirus, Herpes (TORCH) represents a group of important pathogenic infections in the fetus. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is one of the TORCH members and has various pathologic effects on the fetus. Intrauterine CMV infection is an asymptomatic course to a congenital syndrome, and unfortunately, asymptomatic cases may progress to a handicap later (2, 3). Developing countries in Africa (Gambia, Ivory Coast), Asia (China, Korea, Taiwan, India), and Latin America (Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Panama) report the birth prevalence of congenital CMV infection ranging from 0.6 to 6.1% of pregnancies (4). This is higher than the incidence in developed countries as 0.2% - 2% (average of 0.64%) of pregnancies in the US, Canada, Australia, and Western Europe (4-8). Cytomegalovirus inclusion disease manifestations are cutaneous (petechial, purpura, Blueberry muffin baby), hematologic (thrombocytopenia), and CNS (ventriculomegaly, Microcephaly, cerebral atrophy, chorioretinitis). Intrauterine growth retardation, hepatosplenomegaly, and sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) may occur, with SNHL being the most common neurological complication (9). Various studies give relevant information on the importance of CMV in the etiology of SNHL. Today, more than 40% of deafness cases needing rehabilitation, which previously had no known etiology, are attributed to CMV (10).

Other perinatal infections, which are not TORCH group members such as Listeria, are relatively rare but can be the causes of sepsis syndrome and are preventable by health measures. The prevalence of Listeria infection in Iranian food products is high, and it was 52% and 48% in north and west abattoirs (11). Maternal infection by this organism may cause sepsis syndrome in neonates. In a study of early-onset sepsis in neonates in Kashan (2015), two (3.2%) out of 104 positive blood cultures were positive for Listeria (12). Screening of neonates with positive clinical manifestations compatible with these two infections can be an important measure in the early treatment of these infections and prevention of their later complications.

2. Objectives

Since there is not enough information on CMV and Listeria by PCR in Iran, this study aimed to investigate the prevalence of CMV and Listeria in 100 urine samples from neonates under 21-days-old who had positive risk factors for these two infections selected from Tehran referral hospitals.

3. Methods

We obtained 100 urine samples from neonates admitted to Children Medical Center (Markaz Tebbi) and ten other private centers, Tehran, Iran, from June 2013 to December 2014.

Neonates with at least two symptoms of brain calcification, meningitis, prematurity, icterus, microcephaly, convulsion, hydrocephaly, fever, anemia, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly were included in this study. Neonates with known syndromes, culture and PCR-positive infections, or confirmed perinatal infections and chromosomal abnormalities were excluded from this study.

Urine samples were gathered from each neonate by sterile Nelaton tubes directly from the vesicle, divided into six sterile 1.5 mL test tubes and stored at -20°C.

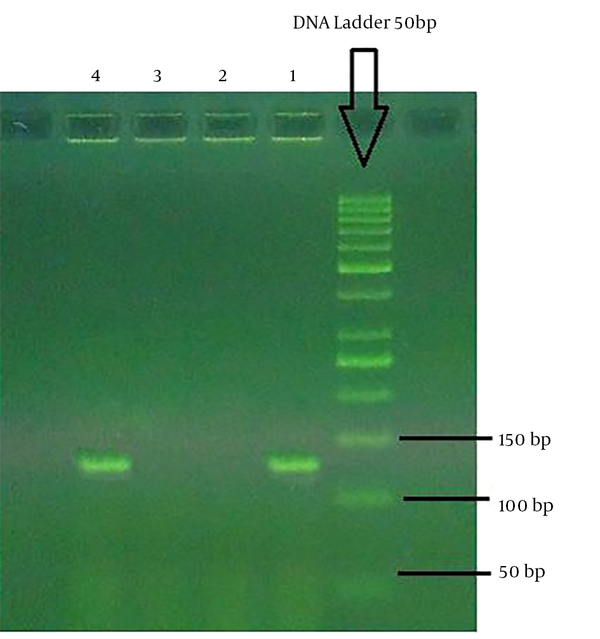

The DNA extraction was done by High pure PCR Template Purification Kit (Roche, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The DNA amplification was done using the fluorescence end-point detection method by Listeria monocytogenes PCR Kit and cytomegalovirus PCR Kit (DNA technology, Russia) according to the kits’ manuals. The kits had the CE/IVD certificates with 95% and 99.5% sensitivity and specificity, respectively. The kits contained specific and internal control primers and probes. No-template control (NTC) was used to monitor potential contamination in the master mix. The PCR assay was repeated twice to confirm the initial findings. The PCR primers are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The PCR gel electrophoresis results for CMV and Listeria are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Data were gathered by questionnaires, and data analysis was performed by SPSS, version 21, software using logistic regression, MacNemar test, and chi-square test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

| Name | Primer Name | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Cytomegalovirus | UL55-F2m | 5’-ATAGGAGGCGCCACGTATTCC-3’ |

| UL55-R2m | 5’-GTACCCCTATCGCGTGTGTTC-3’ | |

| Listeria monocytogenesis | LMF1-2 | 5’- CATCTCCGCCTGCAAGTCC-3’ |

| LMR1-2 | 5’- TTGGCGGCACATTTGTCACTG-3’ |

| Name | Probe Name | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| CMV | UL55-pr2 | (FAM)ATGGCCCAGGGTACGGATCTTATTCGCTGGCCAT(B HQ-1) |

| Listeria | LM-fp1 | AGACGCCAATCGAAAAGAAACACGCGTCT |

4. Results

We collected 100 urine samples from 100 under 21-day-old neonates. The mean age was 9 ± 5 days (2 - 20 days). Seven cases were positive in both Listeria electrophoresis and FEP PCR. Five Listeria cases were males; the mean age was 8.8 ± 4.4 days (4 - 7 days). Moreover, 58 cases were positive in CMV electrophoresis and FEP PCR, 34 of whom were males. The mean age was 11 ± 4.5 days (2 - 20 days). The CMV-positive group had a higher age than the Listeria-positive group (P = 0.000). Three cases were positive for both Listeria and CMV; one case was male, and the mean age was 11.3 ± 4.9 days (8 - 17 days).

Prematurity was the most common clinical finding in both groups, but convulsion and microcephaly were the prevalent clinical findings in the CMV group. Other problems, such as hydrocephaly, fever, anemia, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly, were positive in the CMV group (Table 3).

| Anomaly | CMV Negative | CMV Positive | Listeria Negative | Listeria Positive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcification | ||||

| Negative | 42 | 56 | 91 | 7 |

| Positive | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Microcephaly | ||||

| Negative | 35 | 43 | 72 | 6 |

| Positive | 7 | 15 | 21 | 1 |

| Prematurity | ||||

| Negative | 28 | 41 | 68 | 1 |

| Positive | 14 | 17 | 25 | 6 |

| Convulsion | ||||

| Negative | 32 | 44 | 73 | 3 |

| Positive | 10 | 14 | 20 | 4 |

| Meningitis | ||||

| Negative | 41 | 58 | 92 | 7 |

| Positive | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Icterus | ||||

| Negative | 31 | 49 | 74 | 6 |

| Positive | 11 | 9 | 19 | 1 |

| Othera | ||||

| Negative | 31 | 34 | 59 | 6 |

| Positive | 11 | 24 | 34 | 1 |

aHydrocephaly, fever, anemia, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly.

Table 4 shows the diagnostic accuracy indices along with Mc-Nemar test p values for comparing anomalies (calcification, microcephaly, prematurity, convulsion, and meningitis) based on CMV and Listeria results. The results of the Mc-Nemar test revealed a significant difference between anomaly findings based on the CMV and Listeria results, but there is an agreement between calcification and CMV positive condition; and meningitis and Listeria positive condition (P = 0.18 and 0.07, respectively). This means that brain calcification in CMV-positive and meningitis in Listeria-positive neonates are the expected findings.

| Anomaly | CMV Negative | CMV Positive | P Value | Listeria Negative | Listeria Positive | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcification | SP = 100 | SN = 3.4 | < 0.0001 | SP = 97.8 | SN = 0 | 0.18 |

| NPV = 42.9 | PPV = 100 | NPV = 92.9 | PPV = 0 | |||

| Microcephaly | SP = 83.3 | SN = 25.9 | < 0.0001 | SP = 77.4 | SN = 14.3 | 0.006 |

| NPV = 44.9 | PPV = 68.2 | NPV = 92.3 | PPV = 4.5 | |||

| Prematurity | SP = 66.7 | SN = 29.3 | < 0.0001 | SP = 73.1 | SN = 85.7 | <0.0001 |

| NPV = 40.6 | PPV = 54.8 | NPV = 98.6 | PPV = 19.4 | |||

| Convulsion | SP = 76.2 | SN = 24.1 | < 0.0001 | SP = 78.5 | SN = 57.1 | < 0.0001 |

| NPV = 42.1 | PPV = 58.3 | NPV = 96.1 | PPV = 16.7 | |||

| Meningitis | SP = 97.6 | SN = 0 | < 0.0001 | SP = 98.9 | SN = 0 | 0.070 |

| NPV = 41.4 | PPV = 0 | NPV = 92.9 | PPV = 0 | |||

| Icterus | SP = 73.8 | SN = 15.5 | < 0.0001 | SP = 79.6 | SN = 14.3 | 0.015 |

| NPV = 38.8 | PPV = 45 | NPV = 92.5 | PPV = 5.0 | |||

| Other | SP = 73.8 | SN = 41.4 | 0.001 | SP = 63.4 | SN = 14.3 | < 0.0001 |

| NPV = 47.7 | PPV = 68.6 | NPV = 90.8 | PPV = 2.9 |

Table 5 demonstrates the results of logistic regression for neonatal age and CMV findings. The odds ratio (OR) was equal to 1.17 (95%CI: 1.06 to 1.29; P = 0.001). This means that each day increase in age may increase the chance of positive CMV condition by 17%. Three cases had both infections, all of whom had prematurity, and one case had a convulsion.

| OR | 95%CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMV | 1.17 | 1.06 - 1.29 | 0.001 |

| Listeria | 0.97 | 0.82 - 1.13 | 0.67 |

5. Discussion

Congenital CMV infection is a prevalent disorder, especially in developing countries; the incidence of this infection is 0.7 - 4.5 million infections per year compared to 0.12 million per year in developed countries. The clinical features of this infection include stillbirth, IUGR, preterm birth, brain calcification, sensory neural hearing loss, visual disorders and loss, hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, jaundice, microcephaly, and seizure. However, 90% of cases are asymptomatic at birth, and neurologic handicap may occur in them (13). In a study on saliva specimens from 600 healthy Iranian neonates in the South of Tehran (2012), two cases were positive in CMV PCR, and both of them were asymptomatic. This study did not suggest the screening of congenital CMV infection in Iranian neonates (14). However, it does not rule out the need for CMV screening in children with positive risk factors. There is a time limitation for the diagnosis of congenital CMV infection and the detection of this virus at ages older than two to three weeks can reflect the acquired or breastfed infection (15); thus, our study may reflect the congenital CMV infection.

In 2010, WHO developed an international standardized procedure for quantitative CMV measurement from the National Institute of Biological Standards and Controls in the United Kingdom (16). Reference reagents are now available, and their use allows the viral load to be expressed as international units/mL (17). Our study used both gel electrophoresis and (FEP) PCR for qualitative PCR measurement of CMV in the urine of neonates younger than 21 days with physical findings of probable congenital CMV infection; both results were completely in agreement. This may increase the accuracy of our findings. In a study in South Africa on hospital records of neonates tested for CMV infection, 91% of CMV-infected neonates had low birth weight, 83% were preterm, and 29% were small for gestational age. Hepatosplenomegaly and thrombocytopenia were more likely to occur in CMV-positive neonates (18). In our study, prematurity, microcephaly, convulsion, and hepatosplenomegaly were common findings. Listeria infection in the fetus and neonate is relatively rare. This organism can survive in cold temperatures, and eating contaminated food during pregnancy may cause perinatal infection; its incidence is 2 - 13/100,000 live births. It may occur hours after birth or may be delayed for several weeks. Clinical presentation depends on the timing and route of infection. Neonatal infection with Listeria mostly occurs during and after birth. Listeria accounts for 5% of early-onset sepsis in premature neonates with amnionitis (with a characteristic brown, murky amniotic fluid). Moreover, 70% of Listeria infections occur in infants younger than 35 weeks of gestation, and the late-onset disease is accompanied by meningitis. In our study, six cases of Listeria infection had prematurity, one case had a convulsion, and one case had meningitis. We had no information about the disease in their mothers (19, 20).

In a study in summer 2011, the prevalence of L. monocytogenes was estimated to be 5% in Kerman region raw milk samples (21). In the first study on broiler flocks in the west and North of Iran, L. monocytogenes was isolated from 44 out of 490 flocks and cloaca samples with a prevalence of 8.97% (2010). The potential risk factor for increasing Listeria colonization was the litter quality (11).

From 170 clinical samples from patients with spontaneous abortions hospitalized in Shariati Hospital, Tehran, Iran (2014), using multiplex PCR, 14 cases were positive, and from 107 samples of cheese, cream, and Kashk, nine (8.4%) were positive. In a study on pregnant women with premature delivery or perinatal fever in 2013 in Shandong, China, four neonates (0.34%) were identified with listeriosis by umbilical blood culture and placental swab culture (22, 23). In our study, six neonates who were positive for listeria had prematurity. The high prevalence of Listeria contamination in food may raise the possibility of Listeria infection in neonates in our community.

5.1. Conclusions

The results of this study showed that being aware of possible CMV infection in neonates with brain calcification is important, and meningitis can be a manifestation of Listeria infection. Studies with a higher number of samples are proposed to get precise information about the epidemiology of these two important infections in Iranian neonates.