1. Background

Owing to tiny, flimsy, and small caliber tissues associated with pediatric perineum, the management of urethral strictures needs vigilant consideration of pediatric urology surgeon, once selecting for a reconstructive procedure. Owing to a longer urethra in boys, urethral strictures are much more common than in girls. Traumatic and inflammatory strictures are rare, but it can be caused by congenital, infection, inflammation and traumatic sources’ (1-3). Acquired types of urethral strictures are basically different from the congenital strictures (4). Recent progression in pediatric reconstructive surgery has led to a few innovative aggressive procedures that are suggested as remarkable methods of treatment for urethral strictures. Primary repair that is performed transperinealy is now a generally accepted method of choice for pediatric urethral stricture repair (1). In 47% of boys with urethral strictures, dilation or urethrotomy have been reported unsuccessful with recurrence associated with new strictures on both occasions. Dilation is improper for dealing with most strictures in children and one stage urethroplasty should be considered primarily in the treatment plan since it is desirable to multiple stages.

In those with (1) short bulbar stricture of urethra (2) failed urethroplasty with stenotic annular rings, urethrotomy and dilation are acceptable choices of management. Anastomotic urethroplasty via a perineal approach could successfully repair anterior urethral strictures of the bulb if short, and buccal graft substitution urethroplasty if long. When the defect of the urethra is longer, a transpubic or partial pubectomy posterior anastomotic urethroplasty is needed in most cases. In general, the rate of success for urethroplasty was mentioned in about 83% (4-7). Irritative voiding symptoms, including dysuria, urgency, frequency, initial hematuria may be accompanied with urethral strictures (8-13).

2. Objectives

It is well-known that urethral stricture is a condition that can permanently destruct the total urinary tract if not managed properly. In children, most existed data are usually extrapolated from the adult literature. With this in view, we aimed to study the management of children with urethral strictures in two tertiary hospitals in Isfahan, Iran.

3. Methods

This investigation was conducted at the Isfahan Kidney Transplantation Research Centre (IKTRC). The Institutional Review Board approved the study by ethics code number: 396454. Patients with urethral stricture disease and admitted to the two tertiary hospitals (Alzahra and Khorshid) were recognized. In the first step, urethral strictures were defined according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) by the code (n = 35.9) from hospitals registry databases’. In the second step, all pediatric patients (aged up to 15 years) with urethral strictures were studied for over 10 years from 2008 and 2018. There were no exclusion criteria and a retrospective plan of evaluation was expected for patients regarding basic demographics and clinical management. Microsoft Excel was used to arrange raw data before being inputted into the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS® version 20; IBM Corp., Armonk NY, USA) for analysis. Age, as a continuous variable, was expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The normal distribution of age was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Variables such as gender, age, and type of management were expressed by the frequency and percentage.

4. Results

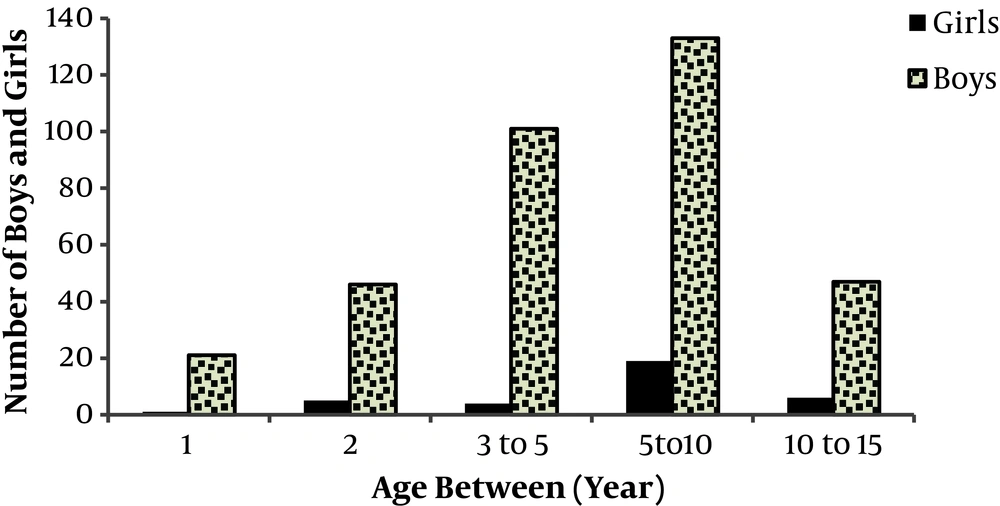

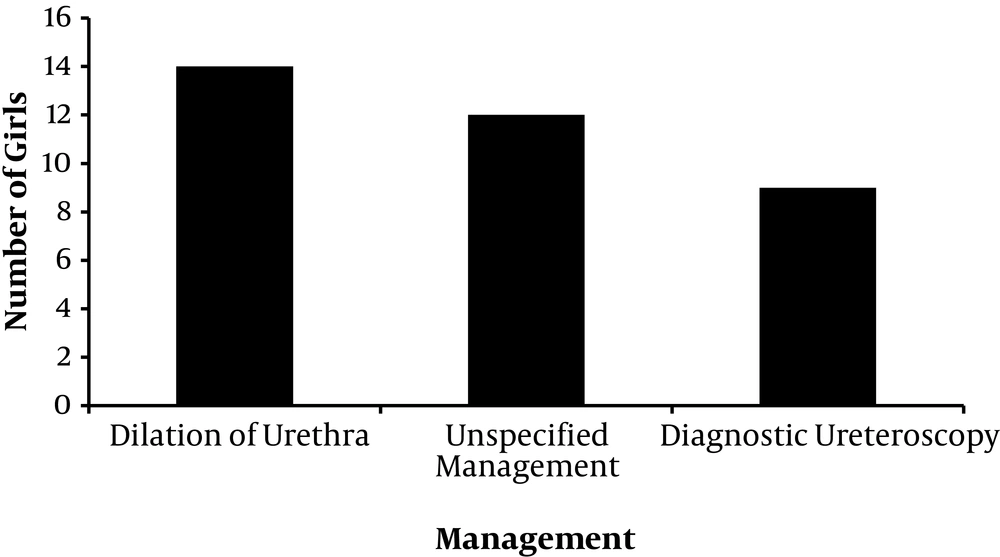

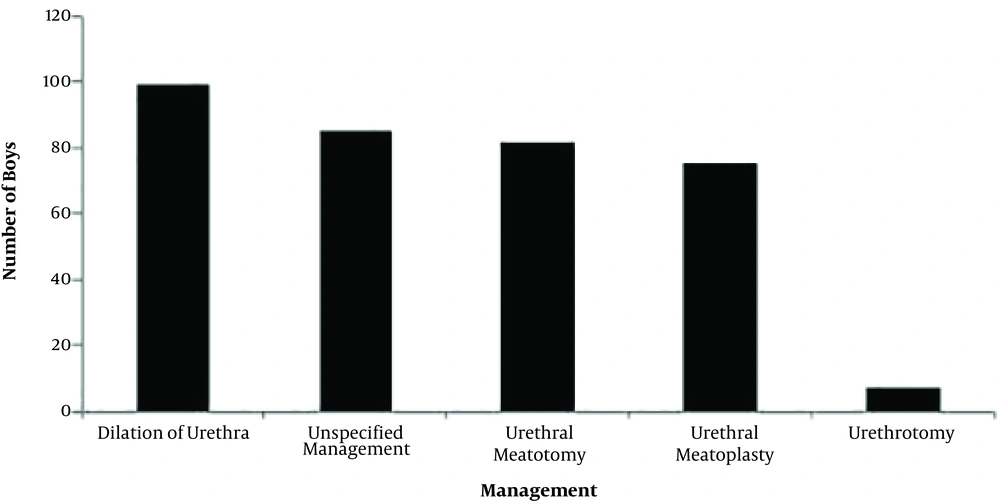

We identified 383 patients with a mean age of 5.5 years for over a period of 10 years. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics in children with urethral strictures. As shown in Figure 1, the study population was comprised of 348 boys and 35 girls. In the total population, the mean ± SD age with a minimum of 1 and a maximum of 15 years was 5.5 ± 3.4 years old. The distribution of age in boys with urethral strictures were as follows: 1 year (n = 21), 2 years (n = 46), 3 to 5 years (n = 101), 5 to 10 years (n = 133), and 10 to 15 years (n = 47). In girls, the distribution of age was categorized as follows: 1 year (n = 1), 2 years (n = 5), 3 to 5 years (n = 4), 5 to 10 years (n = 19), and 10 to 13 years (n = 6). As shown in Figure 2, available data associated with management in girls confirmed: dilation of urethra (n = 14), diagnostic ureteroscopy (n = 7), and unspecified management (n = 12). Figure 3 shows management strategy for boys with the disease of urethra ranked as: dilation of urethra (n = 99), urethral meatotomy (n = 82), urethral meatoplasty (n = 75), urethrotomy (n = 7), and unspecified management (n = 85). Management of disorders associated with the age was shown in Table 2 as there was a significant difference associated with the age at the time of surgery consideration. Statistical analysis based on the Kruskal-Wallis test showed a significant difference between variables (P < 0.0001). The minimum age for urethrotomy in the population studied was at 4 years old. The mean age (year) of 9.1 and 6.4 was associated with urethrotomy and dilation of urethra, respectively that was significantly different from the mean age at the management as meatotomy (4.9) and matoplasty (4.4).

| Number | Mean Age ± SD | Min - Max | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 383 | 5.5 ± 3.3 | 1 - 15 |

| Boys | 348 | 5.4 ± 3.3 | 1 - 15 |

| Girls | 35 | 6.8 ± 3.4 | 1 - 13 |

Abbreviations: Max, maximum; Min, minimum; SD, standard deviation.

| Management in Boys Based on | Number | Min | Max | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dilation of urethra | 99 | 1 | 15 | 6.4 ± 3.6 |

| Urethral meatoplasty | 75 | 1 | 12 | 4.4 ± 2.3 |

| Urethral meatotomy | 82 | 1 | 15 | 4.9 ± 2.9 |

| Unspecified urethral stricture | 85 | 1 | 14 | 4.8 ± 3.4 |

| Urethrotomy | 7 | 4 | 15 | 9.1 ± 3.8 |

Abbreviations: Max, maximum; Min, minimum; SD, standard deviation.

5. Discussion

The challenging conditions urethral stricture in children is a common disease (12) that surgery is recommended as the basis of management in most cases (1). Data about the etiology and clinical history of urethral stricture in children are extrapolated from adult series, and practical facts about this object seem scarce (12). Urethral stricture disease can be caused by iatrogenic, congenital, traumatic, inflammatory or idiopathic etiologies. In our study, in agreement with previous studies, the number of the boys with urethral strictures was 9.9 times higher than the number of the girls (1-14). In this population study, 86.2% of surgical treatments for urethral strictures in children were at the age between 1 to 10 years old.

Previous studies confirmed that meatal stenosis occurs when there are recurrent meatitis and local irritation at the junction of the glans epithelium and urethral mucosa. Epithelium denudation and side-to-side adherence most normally starts centrally and extends toward the glans tip. This decrease in caliber leads to diminished urinary stream and strenuous voiding, which further causes cracking of the meatal edges and meatitis, resulting in dysuria and this vicious circle continues. In the pediatric population, over time, meatotomy has developed as an optimistic procedure that is often done under local anesthesia with or without penile block or under short general anesthesia (12).

In this study, the treatment of urethral strictures was based on dilatation method in most cases. Meatotomy (31%), meatoplasty (28%), and urethrotomy (7%) were the other surgical treatments of choice in children with urethral stricture. This is in agreement with previous published articles that confirmed urethral meatotomy as a type of treatment for meatal stenosis. Furthermore, there is little known data about the patient experience following meatotomy as a common pediatric urology procedure. Similarly, reconstructive meatoplasty is also suggested as a curative method that can be done under a brief anesthetic.

Moreover, previous studies confirmed that discrepancies in stricture etiology may be related to inherent regional differences and practice patterns, access to quality health care, social and environmental settings, or variation in diagnosis that could lead to variation in the manifestation and treatment. In those who are unresponsive to standard therapy (such as neurogenic bladders), dilation of the urethra can be an effective method with no demonstrated long-term effects on continence (1-16).

5.1. Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that 86.2% of surgical treatments for urethral strictures were at the age of 1 to 10 years, and the number of the boys with urethra stricture was 9.9 times higher than the girls. In most cases, the management strategy was based on dilation of the urethra, followed by meatotomy and meatoplasty. The mean age (years) for surgical treatment associated with urethrotomy, dilation of the urethra, meatotomy and matoplasty was as follows: 9.1, 6.4, 4.9, and 4.4, respectively. More extensive studies are needed to recommend the optimum pharmacotherapy guidelines, the length and diameter of stricture, hospital stay as well as overall success rate.