1. Background

The pandemic of COVID-19 disease has caused a lot of stress and anxiety in communities (1). People show any anxious behaviors since January 20, 2020, when China confirmed the human-to-human transmission of disease (2). COVID-19 anxiety is common and often occurs due to a lack of knowledge and scientific information, and ambiguity in people about the virus (3). Various stressors harm coping mechanisms. In an infectious disease, pregnant women and their fetuses are more vulnerable and high-risk people compared to others (4, 5) and are at risk for severe respiratory illness, stress, fear, and anxiety (5). Studies show that excessive fear during pregnancy is associated with increased cesarean section, premature birth, low Apgar score, low birth weight, cardiac dysrhythmia, and increased near-term mortality (6-8). Dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axes and the symptoms of depression in adolescence, and asthma in children, are other side effects of stress during pregnancy (9).

According to studies, spiritual health is a factor that can reduce anxiety. In times of crisis, spirituality is a powerful resource that is a serious barrier to coping with stress and anxiety. Patients whose spiritual health is enhanced can effectively adapt to their illness (10). Although enormous studies have been done since the COVID-19 pandemic, there is still a paucity to show the relationship between COVID-19 anxiety and spirituality during pregnancy.

2. Objectives

This study evaluated the association between COVID-19 anxiety and spirituality in pregnant women in a region in Iran.

3. Methods

The present descriptive-correlation study was performed on 198 pregnant women in 2021 referring to Chabahar health centers, Iran. The data were collected using the convenience sampling method after obtaining the ethics code (IR.ZBMU.REC.1400.054) from Zabol University of Medical Sciences, Iran, and the clients’ consensus. The study samples were pregnant women who were referred to health centers for prenatal care and voluntarily participated in the study. Inclusion and exclusion criteria include having no history of significant psychiatric disorders, no severe physical problems, no complications during pregnancy such as preeclampsia, eclampsia, chorioamnionitis, decolonization, and abnormal fetal heart rate, not using substances or drugs that affect stress and anxiety, and having no significant loss in six months ago.

The data were collected using three questionnaires, including (a) demographic characteristics including age, occupation status, education level, place of residence, and pregnancy history (number of live children, number of pregnancies and deliveries, type of previous delivery, preferred method of current delivery); (b) Coronavirus Anxiety Scale Questionnaire (CDAS2), which measures COVID-19 anxiety. Coronavirus Anxiety Scale Questionnaire measures physical and psychosocial symptoms of covid-19 anxiety with 18 four points Likert-type items. Higher scores indicate a higher level of anxiety. The CDAS2 Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95 (11). The Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS) measures religious and existential well-being with 20 Likert-type items from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Higher scores indicate higher spiritual well-being. The SWBS Cronbach’s alpha was greater than 0.85 (12). Data were analyzed using SPSS 23. A P-value less than 0.05 was set as statistically significant.

4. Results

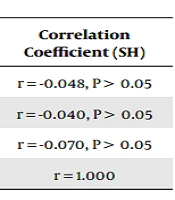

The present study was performed on 198 pregnant women in health centers. The mean age of the subjects was 26.53 ± 6.36 years, and 94.9% of the pregnant women were housewives. About 51% of women had undergraduate education, 28.3% had a diploma, and 19.7% had postgraduate education and higher. The highest level of education of pregnant women was in primary and secondary school (38.4%), 41.5% of the spouses had undergraduate education, 36.4% had a diploma, 20.3% had a postgraduate education and higher, the highest level of education of the spouses was in the diploma level (36.4%). About 97% of pregnant women lived in the city in terms of residence and half of the pregnant women studied in the previous pregnancy had given birth naturally (51.5%) and in the current delivery tended to have a normal delivery (50.5%). Only a small number of women chose cesarean section for various reasons due to obstetrics (11.6%) and 30% were still hesitant about their delivery method. About 93% of women made prenatal visits and observed social distance (96.5%). About 63% of women followed health protocols related to quarantine and 32.3% of people used to travel with their parents and relatives during the epidemic. Only 4% of women continued to travel as before the coronavirus. About 95% of women wore masks (Table 1). The pregnant women’s anxiety scores were severe, and their psychological symptoms were higher compared with their physical symptoms. The mean score of the spiritual health of pregnant women was also high. Table 2 shows that the Spearman correlation test did not show a linear relationship between spiritual health and anxiety caused by COVID-19 (P = 0.501).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Mother education | |

| Non-educated | 26 (13.1) |

| Primary and secondary | 76 (38.4) |

| Diploma | 56 (28.3) |

| Associated degree | 15 (7.6) |

| Bachelor | 17 (8.6) |

| Masters and above | 8 (4.0) |

| Spouse education | |

| Non-educated | 30 (15.2) |

| Primary and secondary | 52 (26.3) |

| Diploma | 72 (36.4) |

| Associated degree | 12 (6.1) |

| Bachelor | 17 (8.6) |

| Masters and above | 15 (7.6) |

| Job | |

| Housewife | 189 (94.9) |

| Worker | 10 (5.0) |

| Address | |

| City | 193 (97.5) |

| Village | 5 (2.5) |

| Type of previous delivery | |

| NVD | 102 (51.5) |

| C/S | 32 (16.2) |

| None* | 61 (30.8) |

| No mentioned** | 3 (1.5) |

| Current delivery | |

| NVD | 100 (50.5) |

| C/S | 23 (11.6) |

| None* | 61 (30.8) |

| No mentioned** | 14 (7.1) |

| Has your desire for a particular type of labor changed since the COVID-19 epidemic? | |

| Yes | 2 (1.0) |

| No | 196 (99.0) |

| Prenatal visit | |

| Yes | 185 (93.4) |

| No | 14 (6.6) |

| Social distance | |

| Yes | 191 (96.5) |

| No | 7 (3.5) |

| During the last few months after the COVID-19 epidemic, which of the following have you observed? | |

| Quarantine | 124 (62.6) |

| Travel relatives only | 64 (32.3) |

| Travels before the COVID 19 | 10 (5.0) |

| Using mask | |

| Yes | 189 (95.5) |

| No | 9 (4.5) |

| Variables | Mean ± SD | Correlation Coefficient (SH) |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety score | 32.05 ± 9.59 | r = -0.048, P > 0.05 |

| Psychological anxiety | 18.95 ± 6.04 | r = -0.040, P > 0.05 |

| Physical anxiety | 13.09 ± 4.70 | r = -0.070, P > 0.05 |

| Spiritual health score (SH) | 103.74 ± 11.20 | r = 1.000 |

5. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic causes catastrophic effects on societies. People in communities have experienced many physical and psychological problems. Religious beliefs act as a shield against stressors in life. This study evaluated the association between spirituality and COVID-19 anxiety COVID-19 in pregnant women. The results did not show any significant relationship between them.

A high level of anxiety declines the immune system function and acts as a backbone to help the virus overcome the health of the person (13). Women’s mental health during pregnancy is influenced by factors such as feelings about femininity, marital life, the spouse’s family, as well as feelings about agreements and conflicts, sexuality, and wanting or not wanting a child. Pregnancy and childbirth have an inevitable effect on women’s bodies and minds (14). Previous studies report a range of 12.5% to 90% anxiety in pregnant women (14, 15). The level of anxiety in pregnant women concerning COVID-19 is very high (16), which is consistent with the present study. Iranian pregnant women have a high prevalence of anxiety in the third trimester of pregnancy (17). The level of anxiety increases with bad and disappointing news about COVID-19 (15).

Moreover, spirituality is related to adaptation ability, expectancy, ability to find the meaning of life in diseases and better adaptation to stressful events (18). The previous studies indicate a statistically significant relationship between high levels of spiritual health and mental health variables (19, 20). However, a study shows no significant correlation between spiritual health and morbid anxiety (21). In the present study, although the spiritual health of pregnant women is at a high level, it did not reduce their anxiety. Religions are expected to increase the quality of life, however, some beliefs that may not emerge from religions but may be known as religious beliefs such as postponing to follow conventional treatment methods or avoiding preventive methods negatively affect people’s health (22).

This study explored pregnant women’s anxiety about COVID-19 and their spiritual health which could be a strength; however, the data were collected at some healthcare centers in a city, which limits the generalizability of findings.

To sum up, COVID-19 anxiety level is high in pregnant women and despite the high level of spirituality; there was not a linear association between the two factors. This may suggest that spirituality cannot correlate with a high level of anxiety during pregnancy. This can lead to pregnant women becoming overly concerned about the health of their fetus, fearing that the fetus will be infected with the coronavirus, and fearing losing the fetus and dying. All of this causes mental disorders in pregnant women and increases their fear and anxiety. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it is recommended to carefully consider the severe anxiety of pregnant women and to offer other measures to reduce it. Different contexts and factors help people to overcome this pandemic safely. Providing accurate and appropriate information on preventive approaches, following health recommendations and cognitive-behavioral therapies, and distance education along with spirituality might help overcome COVID-19 anxiety.