1. Background

Adolescence is characterized by various physical, psychological, and social changes. In this stage of life, adolescents face severe forms of stress and emotion such as anxiety-related emotions (1). Known as a normal emotion, anxiety is an indispensable aspect of life. In other words, everyone experiences anxiety on average; however, it turns into morbid anxiety when it becomes uncontrollable and loses its adjustability (2, 3). Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is among the most common types of anxiety disorder. The GAD is described as an excessive form of anxiety that occurs most days of the week for six months. Hard to control, it does not focus on a specific situation or object and does not emerge as a result of recent stressful events (4). This disorder is mainly characterized by chronic anxiety with severe uncontrollable worries about multiple events or activities in which a person experiences physical and mental symptoms such as muscular tension, irritability, difficulty in sleep, and agitation (5). Students with GAD are so worried about potential events in the future that they cannot easily live at the moment. They are unable to experience and enjoy positive and pleasant ongoing events (6, 7). The natural course of this disorder is chronic and volatile. If left uncured, it will have a weak prognosis (8). According to research studies, GAD can be correlated with excessive anxiety and self-concept clarity disorders (9, 10).

Spielberger (11) divided anxiety into two dimensions, i.e., trait anxiety and state anxiety. The trait anxiety is a personality trait that reflects the frequency and severity of emotional reactions to stress, indicating a person’s relatively stable state of readiness for anxiety. Known as a personality trait, this type of anxiety is not a situational feature that a person faces (12). However, state anxiety is an emotional reaction that differs from one situation to another. Furthermore, trait anxiety and state anxiety are the factors that play minor but active roles in the emergence of GAD (13). This phenomenon often comes to view in a new experience. Its high levels harm a person’s identity and self-confidence (14). Research has also shown that high levels of anxiety are correlated with further depression and lower quality of life (15).

Self-concept clarity can be considered the clarity, stability, and reliability of a person’s self-concept (16). In fact, a person’s self-concept (i.e., his/her all beliefs about himself/herself to describe himself/herself) is present in nearly all life experiences. Moreover, self-concept clarity includes having a distinctive, coherent, and compatible concept of a person’s characteristics (17). People with high levels of self-concept clarity have more self-compatible beliefs. They are less likely to change their self-descriptions over time or use self-descriptive traits of maladjustment such as carelessness and care (18). In addition, self-concept clarity has some benefits for psychological adjustment. Low levels of self-concept clarity are correlated with maladjustment through low self-esteem, high neuroticism, depression, and anxiety (19).

Mode deactivation therapy (MDT) is a treatment method for helping cure adolescents with anxiety. Based mainly on concepts of cognitive theory, the theoretical conceptualization of MDT was developed by correlating spontaneously negative mindsets or cognitive distortions with depression (20). The concept of subjectivism is defined as a network of cognitive, emotional, motivational, and behavioral components designed as integrated sections or subsets of personality to cope with specific problems or requests. They often emerge as instinctive responses in subconscious contexts (21, 22). In addition, Hofmann’s model of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a successful approach to the treatment of anxiety disorders. Hofmann’s model is a conceptual model that uses indirect cognitive reconstruction and situational encounters (23). In this therapy, the main means of change is the gradual encounter that refers to emancipation from an object or a person in order to alleviate distress in the long run. According to Hofmann’s model which was developed mainly to cure a social anxiety disorder, people with anxiety are anxious in social situations because they have high perceptions of social standards (i.e., expectations and social goals) (24).

2. Objectives

Accordingly, this research aims to investigate the effects of MDT and CBT on anxiety and self-concept clarity in students with GAD.

3. Methods

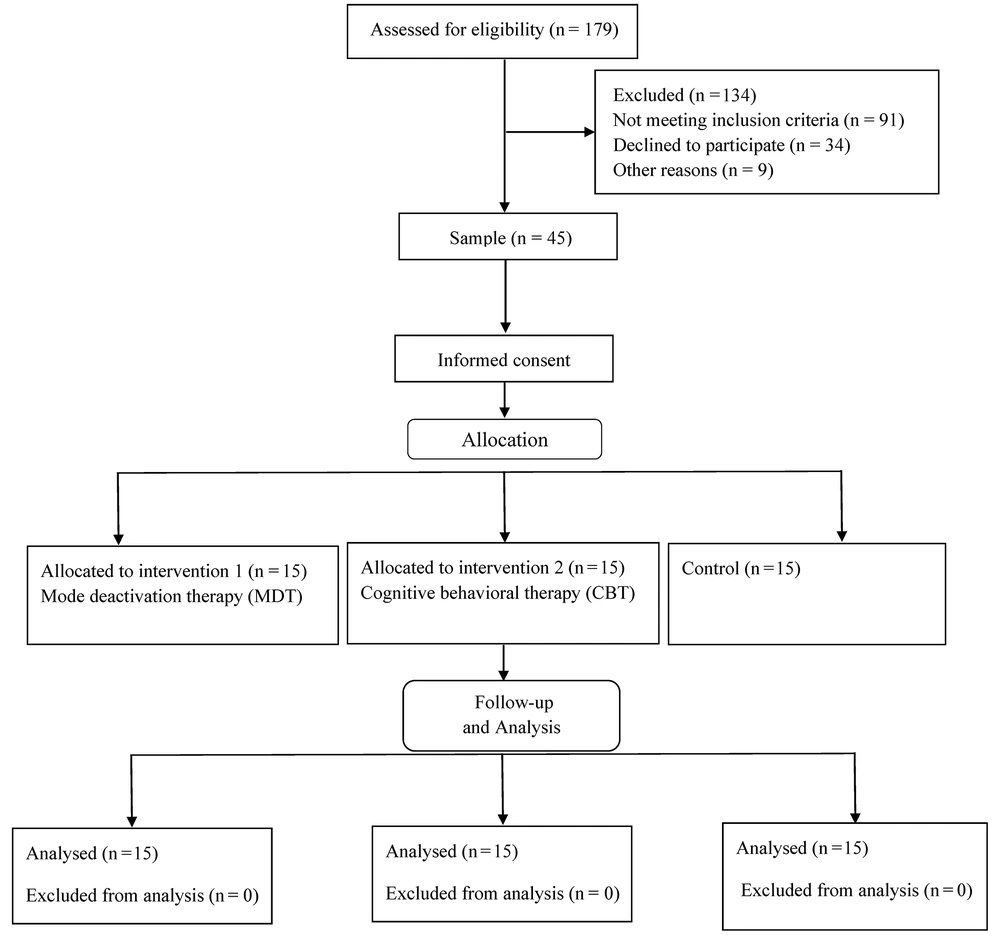

This quasi-experimental research adopted a pretest-posttest design with a control group. The statistical population included all students aged 14 - 18 years old with GAD in Bushehr county (Iran) in 2021. The convenience sampling method was employed to select 45 students as the research sample, who were then randomly assigned to two experimental groups and a control group (15 participants per group using G*Power software with an effect size of 1.10 and test power of 0.90). The inclusion criteria were as follows: Being aged 14 - 18 years old and being diagnosed with GAD based on obtaining a score over 86 on the state-trait anxiety inventory (above 43 in state anxiety and above 46 in trait anxiety). In addition, the exclusion criteria were as follows: Taking psychiatric drugs, receiving any type of psychotherapies, experiencing any psychologically traumatizing events such as the demise of a parent or a loved one in the past six months, and being absent for more than two sessions in interventions.

3.1. Tools

3.1.1. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

Developed by Spielberger (11), this inventory includes two factors (i.e., state anxiety and trait anxiety) and 40 items. The items are scored based on a 4-point Likert scale (ranging from 1: “Too low” to 4: “Too high”). The minimum and maximum scores on this inventory are 40 and 160, respectively, and higher scores indicate higher levels of anxiety. Abdoli and colleagues (25) reported that Cronbach's alpha for internal consistency was 0.88 for trait anxiety and 0.84 for state anxiety.

3.1.2. Self-concept Clarity Scale

Designed by Campbell and colleagues (26), this scale includes 12 items which are scored based on a 5-point Likert scale (i.e., 1: “Strongly disagree”; 2: “Disagree”; 3: “No comment”; 4: “Agree”; 5: “Strongly agree”). The minimum and maximum scores on this scale are 12 and 60, respectively, higher scores indicate higher levels of self-concept clarity. The reliability of this scale was confirmed by Razian and colleagues (27) (α = 0.83).

3.2. Procedure

High school students with GAD were identified among visitors in collaboration with specialized clinics of psychology and counseling in Bushehr county. After identifying a sufficient number of students, the researcher conducted a preliminary interview to explain the research objectives, present ethical principles, respond to potential participant questions, and obtain informed consent forms. The participants were asked to fill out all the measurement tools as the pretest during the preliminary interview. Then each participant was randomly assigned to one of the three study groups (i.e., MDT, CBT, and control) (Figure 1). Based on specific instructions, participants in each experimental group attended the relevant training sessions. The first experimental group received twelve weekly 120-minute sessions of the MDT intervention, an overview of which can be seen in Table 1 (28). The second experimental group received twelve weekly 120-minute sessions of CBT based on Hofmann’s model, an overview of which can be found in Table 2 (29). However, the control group received no interventions. The intervention programs were implemented by the first author as a group. The posttest was conducted when interventions were over in experimental groups.

| Session | Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Acquiring informed consent; establishing therapeutic communication and union; explaining MDT and principles |

| 2 | Emphasizing the value and importance of awareness and observation of problematic or unpleasant thoughts and feelings; explaining internalization and externalization behavior concepts |

| 3 | Explaining the importance of mindfulness and acceptance to eliminate the need to control or avoid negative experiences |

| 4 | Explaining the need to realistically perceive, realize, and evaluate emotional clues and developing emotion regulation skills |

| 5 | Training mindfulness, acceptance, and empathy for oneself and others; presenting mindfulness exercises |

| 6 | Reviewing important principles; analyzing progress; giving feedback; addressing concerns; encouraging patients to describe their experiences in therapy |

| 7 | Explaining impetuses, fears, and beliefs |

| 8 | Explaining all beliefs and behaviors |

| 9 | Introducing the validation, clarification, and redirection (VCR) process; validating a patient’s beliefs through the “seed of truth” |

| 10 | Clarifying a patient’s beliefs and outlooks |

| 11 | Redirecting a patient’s beliefs |

| 12 | Conclusion and posttest |

Abbreviation: MDT, mode deactivation therapy.

| Session | Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Training the basic principles of CBT and presenting the therapy logic; training the basic principles of anxiety symptoms; introducing and discussing the cognitive-behavioral model for anxiety disorder |

| 2 | Reviewing the therapy model; informing patients about anxiety and the role of avoidance in the persistence of anxiety; informing patients about the importance of encounter and the nature of encounter situations; preparing the hierarchy of fear and avoidance; assigning homework: Recording anxiety-inducing events on a daily basis |

| 3 | Familiarizing patients with negative spontaneous thoughts and inefficient beliefs; training patients in skills for identification and classification of negative spontaneous thoughts; challenging thoughts; assigning homework: Completing the form for challenging negative thoughts |

| 4 and 5 | Developing a hierarchy of fear and avoidance; familiarizing patients with the visual feedback technique; having the visual feedback encounters in sessions |

| 6 - 8 | Preparing patients to have encounters in a natural environment outside the therapy sessions; designing an appropriate encounter situation for patients based on the hierarchy of fear and avoidance; having encounters in an environment outside therapy sessions; giving feedback to patients after encounters; assigning homework: Patients are asked to design and implement a few encounter situations to analyze their anxiety levels before and after those encounters. |

| 9 and 10 | Training patients in self-expression tools; familiarizing patients with the courage skill and its different forms; assigning homework: Patients are asked to identify the situations which require self-expression and he used to refuse. Patients are asked to use this skill. |

| 11 and 12 | Preparing participants to confront the temporary relapse of anxiety; reviewing all therapy sessions, summarizing each patient’s progress, and providing patients with feedback |

Abbreviation: CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy.

3.3. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics (i.e., mean and standard deviation (SD)) and inferential statistics (i.e., univariate ANCOVA, multivariate ANCOVA, and post hoc Bonferroni test) were used for data analysis in SPSS-26.

4. Results

Table 3 reports the means ± SDs of state-trait anxiety and self-concept clarity for students with GAD in experimental groups and the control group on the pretest and posttest.

| Variables and Groups | Pretest | Posttest | P (Between Groups) |

|---|---|---|---|

| State anxiety | |||

| MDT | 56.13 ± 5.03 | 41.53 ± 3.33 | 0.001 |

| CBT | 57.87 ± 6.25 | 47.67 ± 5.39 | 0.001 |

| Control | 58.47 ± 7.34 | 58.67 ± 6.23 | 0.936 |

| Trait anxiety | |||

| MDT | 58.20 ± 6.29 | 43.80 ± 5.60 | 0.001 |

| CBT | 57.67 ± 5.80 | 48.47 ± 5.57 | 0.001 |

| Control | 56.80 ± 6.85 | 56.47 ± 4.04 | 0.874 |

| Self-concept clarity | |||

| MDT | 30.40 ± 3.98 | 40.73 ± 3.92 | 0.01 |

| CBT | 29.67 ± 3.05 | 32.60 ± 3.67 | 0.024 |

| Control | 29.27 ± 3.35 | 29.80 ± 3.21 | 0.662 |

Abbreviations: MDT, mode deactivation therapy; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; SD, standard deviation.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

Before data analysis, the hypotheses of ANCOVA (i.e., linearity, multi-collinearity, homogeneity of variances, homogeneity of regression slopes, and normality of distributions) were checked. The pretests of state-trait anxiety and self-concept clarity were considered auxiliary variables (i.e., covariates), whereas their posttests were regarded as dependent variables. Levene’s test results were 1.348, 0.341, and 0.449 for state anxiety, trait anxiety, and self-concept clarity, respectively. These results were not significant at the 0.05 level of significance; hence, the presumption of variance homogeneity was confirmed. Moreover, the pretest and posttest regression slopes were not significant in the experimental groups and the control group, a finding which confirmed the homogeneity of regression slopes. The significance levels of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for state anxiety (0.155), trait anxiety (0.148), and self-concept clarity (0.143) were higher than 0.05; hence, the normal distribution of variables was observed. According to the results, there was a significant difference between the control group and experimental groups in terms of dependent variables. In other words, there was a significant difference between the three groups in terms of at least one of the dependent variables (i.e., state anxiety, trait anxiety, or self-concept clarity).

Table 4 reports the F-values of ANCOVA for state anxiety (F = 105.62 and P < 0.001), trait anxiety (F = 177.77 and P < 0.001), and self-concept (F = 130.66 and P < 0.001). According to these findings, there was a significant difference between the three groups in terms of dependent variables. The Bonferroni test was then employed to determine significant differences between the groups in dependent variables.

| Variables | SS | df | MS | F | P | η2 | Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State anxiety | 1791.74 | 2 | 895.87 | 105.62 | 0.001 | 0.85 | 1.00 |

| Trait anxiety | 1306.88 | 2 | 653.44 | 177.77 | 0.001 | 0.90 | 1.00 |

| Self-concept clarity | 740.01 | 2 | 370.01 | 130.66 | 0.001 | 0.87 | 1.00 |

The Bonferroni test results demonstrated that there was a significant difference between the control group and the two experimental groups (MDT and CBT) in terms of state anxiety, trait anxiety, and self-concept clarity. Hence, MDT and CBT were effective in alleviating state-trait anxiety and improving the self-concept clarity of adolescents with GAD in Bushehr county. There were also significant differences between the MDT group and the CBT group in terms of state anxiety, trait anxiety, and self-concept clarity (Table 5).

| Variables and Groups | Mean Difference | SE | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| State anxiety | |||

| MDT - control | -15.59 | 1.10 | 0.001 |

| CBT - control | -10.63 | 1.07 | 0.001 |

| MDT - CBT | -4.96 | 1.08 | 0.001 |

| Trait anxiety | |||

| MDT - control | -13.49 | 0.72 | 0.001 |

| CBT - control | -8.51 | 0.70 | 0.001 |

| MDT - CBT | -4.96 | 0.71 | 0.001 |

| Self-concept clarity | |||

| MDT - control | 9.89 | 0.64 | 0.001 |

| CBT - control | 2.50 | 0.62 | 0.002 |

| MDT - CBT | 7.39 | 0.63 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: MDT, mode deactivation therapy; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy.

5. Discussion

This research aims to investigate the effects of MDT and CBT on anxiety and self-concept clarity in students with GAD. The results indicated that MDT alleviated state-trait anxiety and improved self-concept clarity. This finding is consistent with the results of Javadi and colleagues (30). A major technique in MDT is to conduct exclusive interviews and administer dedicated questionnaires to identify problematic beliefs, anxiety-inducing situations, scary situations, and a patient’s goals and desires (30). The results of interviews during therapies and those of the dedicated questions can help detect the destructive factors and fears that every participant faces. It will then be possible to accurately determine the causes of anxiety and replace detrimental beliefs with beneficial alternatives (22). An important strategy for this therapy is to identify interventional fears in therapy so that serious obstacles to therapy such as lack of trust, fear of judgment, and avoidance behaviors can be detected and corrected. As a result, a safe environment will be created for patients and therapists to cooperate and participate in the therapy. Firstly, this can help patients to gain self-confidence and believe that they are in control. As they continue feeling further positive self-emotions and having further constructive self-beliefs, they experience lower levels of state anxiety for worries about an inability to manage current situations. Strengthening and perpetuating beneficial alternative beliefs and encouraging patients to practice these beliefs and behaviors will consolidate and deepen them in the belief systems of patients and deactivate their mindsets of fear and incapability (28). Trait anxiety will lessen as a result of not experiencing state anxiety in situations that used to be considered stressful, dangerous, embarrassing, and anxiety-inducing. Hence, patients will experience more peace and further capability. The deactivation of previous destructive mindsets in patients and the creation of alternative functional thoughts can empower them to achieve immediate improvement during therapy sessions and become persistent over time.

The results also indicated that the CBT based on Hofmann’s model mitigated state-trait anxiety and enhanced self-concept clarity. This finding is consistent with the results of Carpenter and colleagues (31). This therapy was designed exclusively to treat anxiety disorders by providing a systematic set of opportunities for patients to help them learn that social situations are not threatening, social mistakes are not embarrassing, and defects in social performance are not as catastrophic as they predict (7). In the CBT sessions based on Hofmann’s model, a therapist should provide patients with new learning opportunities while they pay attention to different methods that they use to avoid learning these new patterns (23). As a result, patients can realize the incorrectness and destructiveness of their previous beliefs. In this regard, a key strategy is to make patients encounter stressful situations so that they let go of the avoidance experience (29). Acting as expert trainers, therapists regulate learning opportunities, guide patients to correctly interpret their current actions (by excluding stressful interpretations and beliefs and providing positive interpretations to prevent shame and anxiety), and adopt humor, motivation, encouragement, and other techniques to help patients test new interpretations and alternatives in most of the stressful and scary situations. After training patterns and theories are presented, the main method of change is a stepwise encounter. For this purpose, a therapist helps patients learn to have encountered through actions, expose themselves long enough to stressful situations, logically evaluate what is happening, and avoid illogical interpretations. Therefore, patients manage to overcome their fears and modify their false expectations (32).

There were significant differences between the MDT and the CBT based on Hofmann’s model in terms of effects on state-trait anxiety alleviation and self-concept clarity improvement. In other words, the results indicated that the MDT was significantly more effective in mitigating state-trait anxiety and enhancing self-concept clarity than the CBT based on Hofmann’s model. This finding is consistent with the results of Swart and colleagues (33). In fact, the MDT identifies the destructive core beliefs that used to cause stressful situations based on weakening faults over the past. This therapy describes such thoughts as detrimental due to not covering natural skills and not having the experiences that everyone gains naturally in the stages of development (33). In addition to confirming that such beliefs are natural in the conditions experienced by participants, the MDT changes destructive beliefs into constructive beliefs through the validation, clarification, and redirection (VCR) process. It also includes various exercises and assignments (e.g., the theoretical foundation of therapy, cognitive-behavioral sequence, and identification of life goals) to teach patients that they can properly handle stressful situations without the fear of being threatened and judged by having confidence in their abilities and beliefs in self-efficacy in the face of natural anxiety (34). The VCR process is considered an active therapeutic element in MDT. Hence, this approach differs from the suggestions made by conventional CBT techniques in which acceptance and validation are forcefully projected upon patients. Due to unconditional positive attention and mindfulness, beneficial alternatives are nurtured in patients instead of challenging and attacking detrimental core beliefs directly as illogical and unrealistic mindsets (35).

5.1. Limitations

The statistical population included only the students with GAD in Bushehr county (Bushehr province, Iran). Hence, caution should be taken into account while generalizing the research results to other age and cultural groups.

5.2. Conclusions

In general, the research results indicated that MDT was more effective than Hofmann’s model of CBT in mitigating state-trait anxiety and enhancing the self-concept clarity of students with GAD. In fact, MDT includes a combination of theoretical principles and practical CBT techniques, acceptance and commitment therapy, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, and dialectic behavioral therapy. Therefore, it is more effective. Given the therapeutic purposes of the MDT, it would be a good idea to employ this therapy method for curing adolescents with conduct disorders, especially anxiety, and depression.