1. Background

Today, many individuals, especially female heads of households, lack the essential abilities and necessary skills to cope with life challenges. This has rendered them vulnerable in facing the challenges and difficulties of life (1). Despite the establishment of numerous institutions and organizations for the research and education of female household heads, as well as the substantial costs incurred, these women continue to face issues and problems stemming from poverty (2). As such, their quality of life has been compromised. A low quality of life leads to a situation where female heads of households are more exposed to social vulnerabilities compared to other family members (3). Given that a significant group of female heads of households face poverty, disability, and powerlessness, particularly in managing household economic affairs, their self-esteem and mental health are affected, which has paved the way for depression, anxiety, and other disorders (4, 5).

Characterized by the fear of negative evaluation by others in various social situations, social anxiety is one of the influential variables affecting the quality of life of female heads of households (5). It affects an individual's performance and can lead to hesitance in initiating relationships with others in order to avoid judgment. Social anxiety is characterized by a distinct fear or anxiety regarding one or more social situations in which individuals anticipate scrutiny and fear negative evaluation due to their behavior or the manifestation of anxiety symptoms (6). Being in social situations is almost always accompanied by anxiety for individuals with this disorder, and they try to avoid such situations or endure them while suffering severe anxiety (7, 8). Studies have shown that women with social anxiety experience significantly lower quality of life, particularly in terms of general health, vitality, social functioning, and psychological well-being (9). Dehdashti Lesani et al. (5) demonstrated that emotional suppression and emotion regulation difficulties correlated inversely with the quality of life of female heads of households, with these factors serving as predictors of variations in their quality of life.

In recent years, clinical researchers have paid more attention to studying thought patterns in emotional disorders and the role of intrusive thoughts in emotional disorders. One of these patterns is rumination, which involves a tendency to repeatedly think about the causes and consequences of negative emotional experiences. In other words, rumination is passive and repetitive thinking about stressful matters (10). Rumination primarily consists of nonverbal thought processes in which the individual analyzes potential threats and strives to find solutions to problems and ways to avoid danger (11). This thinking pattern often occurs in response to initial automatic negative thoughts. The problem with rumination is that it has long-lasting negative effects and causes anxiety (12). Moreover, it directs the individual's attention toward ideas and processes that reinforce ineffective knowledge (13). Experimental studies have shown that rumination intensifies negative affect and cognition (14). This intensification leads to negative and, in some cases, dangerous outcomes, including clinical symptoms such as depression, pessimistic thinking, and ineffective problem-solving (15).

Research indicates that there are various methods and therapeutic techniques available for changing and reducing mental health problems in women (16). One such therapeutic technique is compassion-focused therapy (CFT). Compassion-focused therapy is a multidimensional process that aims to transform individuals' self-evaluations and focuses on exercises in relaxation, self-compassion, and mindfulness, which significantly promote calmness and improve the overall quality of life (17). This therapeutic approach includes three components: Self-compassion instead of self-judgment, human connections instead of isolation, and vigilance against excessive self-criticism (18, 19). Self-compassion serves as an effective protective factor in fostering emotional flexibility (20). Recently, therapeutic methods have been developed to enhance self-compassion. Compassion-focused therapy promotes support and kindness towards oneself and is negatively associated with self-criticism, depression, anxiety, and rumination (21). Stroud and Griffiths (22) reported that compassion-focused treatment is an effective intervention for improving mental health in adults. Vidal and Soldevilla (23) reported that CFT reduces self-criticism and increases the ability to experience tranquility. Khoshvaght et al. (24) demonstrated the effectiveness of CFT in reducing anxiety and depression in mothers of children with cerebral palsy.

Female heads of households assume the responsibility of providing care, custody, and support for their children and dependents due to the absence or unhealthy presence of a male figure within the family unit. Attention to the quality of life of these women has proven to be effective in reducing their psychological and personal distress and improving their daily relationships and overall well-being. As mentioned, emotional capabilities play a significant role in successful relationships and psychological adaptation and enhance the individual's ability to organize and control social interactions. Considering the widespread prevalence of social anxiety and rumination among women, their associated problems and challenges, and the emotional and economic costs they impose on individuals and society, it is necessary to address explanatory patterns and therapeutic approaches for these disorders.

2. Objectives

Previous studies have not specifically examined the impact of CFT methods on the psychological characteristics of female heads of households. Accordingly, this study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of compassion-focused therapy on social anxiety and rumination among female heads of households.

3. Methods

This study employed a quasi-experimental design with a pretest, a posttest, and a control group. The statistical population of the research consisted of all female heads of households visiting the welfare centers in Aligudarz (Iran) in 2022. The sample included 40 participants selected through purposive sampling and based on the inclusion criteria. The participants were randomly assigned to an intervention group and a control group, with each group consisting of 20 individuals. The sample size was calculated based on G*Power software (effect size = 0.95), alpha = 0.05, and test power = 0.90. In this study, female heads of the household were placed in two control and experimental groups using a random number table. The inclusion criteria for the study included voluntary consent to participate, being a head of household, having at least a secondary education, age between 30-50 years, no drug abuse, and no concurrent participation in other treatment programs. The exclusion criteria included the use of psychiatric medications, unwillingness to cooperate with the research, and absence for more than two sessions. In order to comply with the ethical principles of the research, informed consent was obtained from all the participants selected to participate in the study and they were assured that the data would be kept confidential.

3.1. Intervention Program

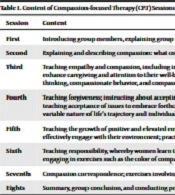

The CFT program comprised eight 90-minute sessions held weekly for the experimental group, based on Gilbert's (25) CFT model. The content of the CFT sessions is summarized in Table 1.

| Session | Content |

|---|---|

| First | Introducing group members, explaining group rules, providing information about distress tolerance and resilience, and introducing the basics of CFT. |

| Second | Explaining and describing compassion: What compassion is and how it can be applied in CFT to overcome problems. |

| Third | Teaching empathy and compassion, including instruction on developing and experiencing a wider range of emotions in relation to individuals' issues to enhance caregiving and attention to their well-being; thinking about compassion towards others; focusing on and cultivating compassion, compassionate thinking, compassionate behavior, and compassionate visualization. |

| Fourth | Teaching forgiveness; instructing about accepting mistakes and forgiving oneself to facilitate the process of making changes; increasing mindfulness; teaching acceptance of issues to embrace forthcoming changes; building the ability to endure difficult and challenging circumstances in light of the variable nature of life's trajectory and individuals' encounters with various challenges; wisdom, strength, warmth, and non-judgment. |

| Fifth | Teaching the growth of positive and elevated emotions, including instructing individuals to help them generate valuable emotions within themselves to effectively engage with their environment; practicing mindfulness and self-awareness; examining beliefs associated with unhelpful emotions. |

| Sixth | Teaching responsibility, whereby women learn to have self-critical thinking and develop new perspectives and more effective emotions within themselves; engaging in exercises such as the color of compassion, the sound and image of compassion, and correspondence based on compassion. |

| Seventh | Compassion correspondence; exercises involving anger and compassion; exercises addressing the fear of compassion. |

| Eights | Summary, group conclusion, and conducting posttests. |

3.2. Research Tools

Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN): This questionnaire was developed by Connor et al. (26) to assess social anxiety. It is a 17-item self-report scale consisting of three subscales: Avoidance (7 items), fear (6 items), and physiological discomfort (4 items). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from "not at all" to "extremely". The total score on this instrument ranges from 0 to 68. Rezaei Dogaheh (27) reported a reliability of 0.87 and confirmed the reliability of the scale.

Rumination Response Scale (RRS): Nolen-Hoeksema et al. (28) developed a self-report questionnaire that assesses four different response styles to negative moods. The RRS consists of 22 items, each rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from "never" to "always". The questionnaire includes three subscales: Reflection, brooding, and depression. Cronbach's alpha was 0.90 in Aghebati et al.'s research (29).

3.3. Data Analysis

The data in this study were analyzed at descriptive and inferential levels using SPSS version 27, with a significance level set at 0.05. Descriptive measures such as mean and standard deviation were used to describe the variables at the descriptive level. At the inferential level, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) and Bonferroni post hoc tests were employed.

4. Results

A total of 40 female heads of households, with an average age of 38.20 ± 5.73 years, were assigned to two groups of 20 participants each: The CFT intervention group and the control group. Table 2 presents the calculated mean and standard deviation of the pretest and posttest scores for social anxiety and rumination among female heads of households.

| Variables and Groups | Pretest, Mean ± SD | Posttest, Mean ± SD | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social anxiety | |||

| Intervention group | 57.65 ± 4.49 | 29.95 ± 4.26 | 0.001 |

| Control group | 58.35 ± 4.97 | 57.75 ± 5.59 | 0.722 |

| Rumination | |||

| Intervention group | 57.00 ± 5.20 | 39.70 ± 4.29 | 0.001 |

| Control group | 58.65 ± 5.67 | 57.90 ± 4.71 | 0.652 |

The assumption of data normality was examined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Based on the results, the assumption of normality for social anxiety in the pretest (Z = 0.107, P = 0.200) and posttest (Z = 0.124, P = 0.122) and rumination in the pretest (Z = 0.109, P = 0.200) and posttest (Z = 0.127, P = 0.102) among female heads of households was confirmed. Levene's test results indicated equal variances for social anxiety (F = 0.125, P = 0.725) and rumination (F = 0.279, P = 0.615) variables across different levels of the independent variable.

The results of analysis of covariance revealed that the CFT intervention significantly affected at least one of the dependent variables among female heads of households (P < 0.001). Based on Table 3, a significant difference was observed between the groups in terms of social anxiety (F = 406.05, P < 0.001) and rumination (F = 186.07, P < 0.001) among female heads of households.

| Variables | SS | df | MS | F | P-Value | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social anxiety | 7472.67 | 1 | 7472.67 | 406.05 | 0.001 | 0.92 |

| Rumination | 3011.64 | 1 | 3011.64 | 186.07 | 0.001 | 0.83 |

Table 4 presents the results of the modified Bonferroni post hoc test, comparing the effect of the intervention types on social anxiety and rumination among female heads of households. Based on Table 4, the CFT intervention improved social anxiety and rumination among female heads of households (P < 0.001). In other words, the comparison between the CFT intervention group and the control group showed a significant reduction in social anxiety and rumination among female heads of households.

| Variables | Phase | Group | Mean Difference | SE | P-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||||

| Social anxiety | Posttest | Intervention | Control | -27.41 | 1.36 | 0.001 | -30.17 | -24.66 |

| Rumination | Posttest | Intervention | Control | -17.56 | 1.29 | 0.001 | -20.17 | -14.95 |

5. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of CFT on social anxiety and rumination among female heads of households. The results indicated that CFT improved social anxiety and rumination among female heads of households. In other words, this therapeutic approach reduced social anxiety and rumination among female heads of households. These findings are consistent with the results of previous studies (22, 24). The effectiveness of CFT on social anxiety can be explained by the way it instructs individuals to cultivate traits such as kindness, self-understanding, and the avoidance of excessive self-criticism. Additionally, it encourages individuals to accept difficulties and hardships without engaging in inappropriate self-judgment (22). Therefore, increasing intimacy through CFT, enhancing social support, promoting self-esteem, facilitating positive social feedback, fostering emotional and cognitive connectedness with others, and empathizing with others' emotions reduce social anxiety among female heads of households.

Compassion-focused therapy helps female heads of households to accept their emotions as they are and to have realistic expectations of themselves. This process allows them to experience less perceived anxiety. As such, they can engage in psychological acceptance and psychological tranquility. Furthermore, they demonstrate more evolved emotional and psychological processing and acquire higher resilience (30). The primary root of compassion lies in life pressures and stressful conditions. Rather than being a negative or neutral emotional pattern, it acts as an effective emotion regulation strategy and creates a foundation for the emergence of greater positive emotions from self-compassion. It is important to note that self-compassion allows women to establish emotional security within themselves. This enables them to see themselves clearly without the fear of self-criticism (24). Additionally, self-compassion allows women to better perceive and rectify incongruous cognitive, emotional, and behavioral patterns. Therefore, self-compassion does not lead to passivity and stagnation. Instead, self-compassion becomes an influential factor in adaptive psychological functioning (21). Self-compassion is negatively related to depression, self-criticism, and rumination, while positively related to life satisfaction, fulfillment of fundamental psychological needs, social connectedness, and positive emotions (31). Consequently, it can reduce anxiety and feelings of shame and contempt.

Self-compassion requires accepting the fact that failure and imperfection are part of the human condition and that all humans, including oneself, deserve kindness and compassion. Self-compassion is distinct from self-pity, as when a person feels pity and tenderness towards themselves, they are more likely to feel disconnected from others and become more absorbed in their own problems, forgetting that others also have similar (and sometimes worse) difficulties (18). Therefore, feeling pity and tenderness exacerbates and prolongs personal suffering, as it further engulfs the individual in their own emotions and makes it difficult to distance themselves from emotional situations. Individuals who have high levels of self-compassion respond to negative events by treating themselves with kindness, concern, and gentleness (20). A high level of self-compassion leads to increased social connection and reduced self-criticism, rumination, suppression of thoughts, and anxiety.

In self-compassion-focused training sessions, in addition to teaching compassion and its principles, each session is dedicated to a specific self-compassion exercise. Examples of these exercises include rhythmic calming breathing exercises, identifying self-critical thoughts and behaviors, increasing mindfulness in tracking thoughts and emotions, practicing self-compassionate meditation and imagery, and keeping a daily journal of self-compassionate thoughts (19). In self-compassion intervention, women learn not to avoid or suppress their painful emotions. Consequently, they can first acknowledge their experience and have a sense of self-compassion towards it. Subsequently, they adopt a compassionate attitude towards themselves. In CFT, the emphasis is on experiencing unpleasant emotions without suppressing or escaping from them. In this therapeutic approach, the focus shifts from self-compassion to changing individuals' self-evaluation and transforming their relationship with self-evaluation. This therapeutic model is effective in helping individuals with high levels of shame, self-criticism, and self-blame (31).

5.1. Limitations

This study did not include factors such as socioeconomic status and other stress-inducing factors that could potentially impact the research outcomes. The research was limited to women as household heads in Aligudarz. Conducting the research on a larger scale could have resulted in more generalizable results. The data collection tools were also limited to self-report questionnaires.

5.2. Conclusions

Given the effectiveness of group-based CFT in reducing social anxiety and rumination among women as household heads, it is recommended to provide group-based CFT training to counselors and therapists in welfare centers. By implementing this educational approach, counselors and therapists can take practical steps toward improving the mental health of women as household heads. It is also recommended to conduct this study in other communities with different socio-demographic characteristics to enhance the generalizability of the results. Furthermore, it is suggested that future research include follow-up data collection after conducting posttests to examine any changes in the results over time.