1. Background

Adolescence is an important stage in a person's social and psychological development, where he/she needs to strike an emotional balance, especially between emotion and logic, perceive self-value, achieve emotional independence from family and surroundings, establish healthy relationships with others, and acquire social skills required to make friends (1, 2). Lack of emotional autonomy, maladaptation and social anxiety, low self-esteem, failure in education and career, and depression—one of the most prevalent mental illnesses over the past 20 years—are among the main issues with which adolescents are faced nowadays (3). Despite all the previous efforts, the research literature indicates that depression remains the primary cause of disability for individuals aged 12 – 44 years (4). The rate of depression in adolescents in 2019 was reported as 15.8% (5). It is also expected to be the leading cause of disease burden by 2030 (6). Depression is the outcome of social factors, psychological processes, and biology rather than just a biological problem (7). Stress, social anxiety disorder, maladaptation, lack of emotional autonomy, depression, and anxiety can all negatively affect the abilities and, ultimately, the fate of adolescents (8). Adolescence is a sensitive stage that needs to be handled, especially for students. Depression, emotional difficulties, and social maladaptation are only some of the issues that need to be addressed in this period.

Emotional autonomy, or the ability to remain largely unaffected by extrinsic factors, is a function of sound self-esteem, self-confidence, self-efficacy, spontaneity, and responsibility (9). In other words, emotional autonomy is a state of equilibrium between emotional reliance and non-conflict (10). Autonomy is a crucial characteristic that marks the transformation from childhood to adolescence (11). A person's parental attachment contradicts many aspects of his/her developing autonomy during the transition into adulthood, which has an immediate effect on the degree and quality of actual autonomy. Not only is real autonomy a "value-cognitive plan of oneself in the future", but it is also the outcome of active metallization tools and strategies aimed at dealing with the frustrating aspects of adult life and age-related tasks (10). Failure to overcome any of these challenges can cause depression and lead adolescents to experience low levels of life satisfaction (12).

The concept of emotion regulation refers to a person’s endeavor to manage his/her own emotions as well as those of others (13). There are two categories of emotion regulation strategies: Healthy and unhealthy. This effect has a positive outcome in healthy strategies and a negative outcome in unhealthy ones (14). Emotion regulation is the ability to monitor, evaluate, comprehend, and modify emotional reactions in a way that promotes normal functioning (15). Emotion regulation refers to the process whereby individuals regulate their emotions either consciously or unconsciously by altering their experiences or changing the situation that causes those emotions (16). Accordingly, emotions are both intrinsic and extrinsic processes that regulate, assess, and modify an individual's emotional responses while they work toward their objectives. Any issues or defects in this process can lead to mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety as well as physical symptoms (17). Evidence suggests that cognitive strategies such as rumination, self-blame, and catastrophizing are positively correlated with depression and other pathological aspects. By contrast, this correlation is negative for strategies such as positive reappraisal (18, 19). Therefore, the study of interventions that promote the self-regulation of emotions can be an effective step toward helping patients with depression.

Psychotherapy and drug therapy are commonly used to treat depression. Although antidepressants are a reliable and effective treatment for this disorder, at least one-third of patients with depression do not respond well to standard antidepressants (20). As a result, they either experience treatment side effects and take longer to respond to treatment or experience a relapse of the illness after stopping the medication (21). Although a growing number of individuals take antidepressants, there are still people who refuse pharmacotherapy because they do not respond to it or are concerned about the side effects. As a result, there is a growing interest in non-pharmacological treatments (22). Emotionally focused therapy (EFT) is one of the non-pharmacological treatments that can improve depression and its symptoms (23). This treatment, which combines experimental and systemic approaches, can effectively mitigate psychological issues (24). Emotionally focused therapy consists of three overlapping stages: Connection and awareness, recall and discovery, and emotional reconstruction in eight steps (25). The therapist serves as a guide and facilitator for the client's goals, with the understanding that the client specializes in the analysis of his/her own experience throughout treatment (26).

According to EFT, a person's helplessness stems from the way they structure and interpret their emotional experiences as well as the patterns of interaction they develop and fortify (27). The two main objectives of EFT are to encourage positive interactions and help clients access latent emotions. Emotionally focused therapy generally aims to assist clients in accessing, expressing, and reprocessing the emotional responses that form the basis of their unfavorable interaction patterns (28). Amini et al. (29) showed that EFT increased the application of positive cognitive techniques for controlling emotions and lessening the intensity of emotional failure in students with symptoms of inclination towards the Internet and cyberspace.

More attention is being paid to the treatment and reduction of symptoms in affected individuals than ever before due to the severe emotional, social, and economic pressure that depression disorder sufferers, their families, and society bear, as well as the disorder's growing annual prevalence in the general population.

2. Objectives

Considering the importance of minimizing depression symptoms and their detrimental effects on students' psychological well-being and addressing issues such as poor emotional regulation and lack of emotional autonomy, this study aims to analyze the effects of EFT on emotional autonomy and emotion regulation of students with depression symptoms.

3. Methods

This quasi-experimental research adopted a pretest-posttest control group design with follow-up. The statistical population included all high school students with depression symptoms in Ahvaz, Khuzestan Province (Iran) in the academic year 2022–2023. The purposive sampling technique was employed to select 30 students with depression symptoms. Among the students who visited the psychological centers of Ahvaz, those who met the inclusion criteria (i.e., being diagnosed with depression symptoms by a psychologist according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) and Beck's Depression Inventory) were selected as the sample. The exclusion criteria were also unwillingness to continue the study, affliction with a psychotic disorder, absence in more than two therapy sessions, taking other medications for depression, and incomplete questionnaires. The participants were randomly assigned to an experimental group (n = 15) and control group (n = 15). The specified sample size was selected based on G*Power software with a test power of 0.90, an effect size of 1.59, and a significance level of 0.05. Participants in the experimental group attended ten 45-minute sessions of EFT once a week, whereas those in the control group received no intervention. In addition, all participants filled out the Emotional Autonomy Scale (EAS) and the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) at the pretest, posttest, and follow-up stages. The follow-up stage was implemented one month after the posttest. Informed consent was obtained from the students and their parents before the research.

3.1. Measurement Tools

3.1.1. Emotional Autonomy Scale

This 13-item scale was developed by Steinberg and Silverberg (30) to measure three factors: Individuation (items 1, 2, 3, 4, and 12), non-dependence (items 5, 6, and 7), and self-reliance and parental de-idealization (items 8, 9, 10, 11, and 13). The items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale (from 1: Strongly disagree to 4: Strongly agree). The range of Emotional Autonomy Scale (EAS) scores is 13 to 42, and higher scores indicate greater emotional autonomy. In our study, the reliability coefficient was 0.79 for the EAS.

3.1.2. Emotion Regulation Questionnaire

Developed by Gross and John (31), Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) has 10 items in two subscales: Reappraisal (6 items) and suppression (4 items). The items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale (from 1: Strongly disagree to 7: Strongly agree). The range of scores for the reappraisal subscale is 6 to 48. Also, the range of scores for suppression is 4 to 28. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.84 for the ERQ.

3.2. Intervention

The EFT intervention was developed and planned using the model proposed by Johnson and Greenberg (32). Emotionally focused therapy sessions were conducted in groups at the Porsina Counseling Center in Ahvaz. Moreover, the sessions were conducted by a psychotherapist who had completed specialized courses. Table 1 presents an overview of EFT sessions.

| Session | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction of group members; How parents behave when their adolescents reject them: The passive, occasionally domineering adolescent |

| 2 | Parents are briefed on the characteristics of adolescence such as privacy and independence, discussing the parents' fear of losing their adolescents and the mistakes they make in order to control them, discussing the characteristics of adolescents who use secure attachment styles |

| 3 | Key concepts in a vicious dialogue are explained; it is explained that humans respond to three lifestyles: Passive, aggressive, and daring |

| 4 | Parents navigate their challenges through a vicious cycle; adolescence-related concerns are brought up, followed by a discussion of the issues the participant faces in that area |

| 5 | Exercise 1: Establishment of emotional communication: The adolescent introduces and positively describes each parent on a piece of paper – each parent gives a one-sentence description of their adolescent on a separate piece of paper. Exercise 2: Identification of parents of adolescents based on positivity: Parents and adolescents each write down what they enjoy doing and make assumptions about one another. Exercise 3: Security prioritization: Both parents and adolescents are asked to talk about their best and happiest times in their family groups |

| 6 | Adolescents are asked to discuss what characteristics they have and how those characteristics make their parents unhappy and also their thoughts, physical reactions, and how they see their families when they are in a destructive cycle. |

| 7 | Adolescents were asked to talk about why they think their parents are repeatedly fighting with them. They were asked if they would prefer to spend time with their parents or their peers and why? |

| 8 | Common negative behavioral patterns are discussed; if we cannot access our children, we try to use any behavior such as negligence, indifference, lack of care, or being very intrusive and critical. How upset will the adolescents be if their parents distance themselves and occupy themselves in order to shield themselves from the worry that they will not be able to connect with the adolescent? |

| 9 | Adolescents bring their problems into the vicious dialogue and use the vicious cycle to recognize their behavioral errors. Parents and adolescents collaborate to keep this cycle from taking over their relationships |

| 10 | Parents drag their problems into a vicious cycle and repeat it over and over. At the end of the session, the adolescents and parents are asked to share their current emotions and provide feedback regarding the sessions. |

3.3. Statistical Analyses

The kurtosis and skewness indices and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test were used to evaluate the normal distribution of the data. Levene's test was also used to check the homogeneity of variances. Finally, the research data were analyzed through the repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). The obtained data were entered into the SPSS v23. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

4. Results

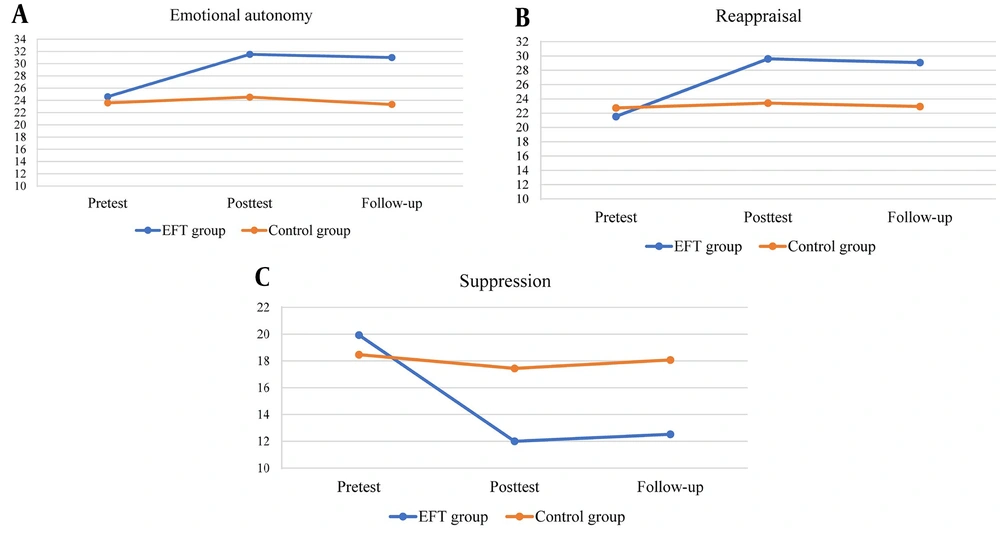

The participants in this research included 30 female students with depression in the age range of 13 to 18 years. The average age of the students in the experimental and control groups was 17.25 ± 2.68 and 16.77 ± 3.12 years, respectively. Table 2 reports the pretest, posttest, and follow-up mean scores of emotional autonomy and emotion regulation in the experimental and control groups. According to Table 2, EFT significantly changed emotional autonomy and emotion regulation strategies (i.e., reappraisal and suppression) in the experimental group in the posttest and follow-up stages (P < 0.001). However, such a significant difference was not observed in the test group. In addition, there was no significant difference between the posttest and follow-up stages in the effectiveness of EFT in any of the experimental and control groups (Figure 1).

| Variables and Phases | EFT Group | Control Group | P-Value (Between Groups) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional autonomy | |||

| Pretest | 24.60 ± 3.96 | 23.60 ± 3.62 | 0.476 |

| Posttest | 31.53 ±4.30 | 24.53 ± 3.73 | 0.001 |

| Follow-up | 31.00 ± 4.25 | 23.33 ± 3.49 | 0.001 |

| Reappraisal | |||

| Pretest | 21.53 ± 2.99 | 22.73 ± 2.84 | 0.269 |

| Posttest | 29.60 ± 2.47 | 23.40 ± 3.11 | 0.001 |

| Follow-up | 29.07 ± 2.65 | 22.93 ± 3.03 | 0.001 |

| Suppression | |||

| Pretest | 18.93 ± 2.21 | 18.47 ± 2.50 | 0.598 |

| Posttest | 12.00 ± 2.00 | 17.44 ± 1.99 | 0.001 |

| Follow-up | 12.53 ± 1.72 | 18.07 ± 1.83 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: EFT, emotionally focused therapy.

To ensure that the research data met ANOVA assumptions, they were examined using kurtosis and skewness indicators. According to the results, the kurtosis and skewness of all variables ranged between -2 and +2. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test also showed that the data on emotional autonomy (Z = 0.08, P = 0.200), reappraisal (Z = 0.11, P = 0.161), and suppression (Z = 0.13, P = 0.092) followed a normal distribution pattern. The results of Levene’s test for examining the homogeneity of variances also demonstrated the homogeneity of variances in all three research variables in both groups.

Table 3 presents the results of the repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) for all research variables at three stages. The findings revealed a significant difference between pretest, posttest, and follow-up mean scores of emotional autonomy (F = 710.08, P = 0.001), reappraisal (F = 851.73, P = 0.001), and suppression (F = 330.09, P = 0.001). The results also showed that the interaction between group and time was statistically significant for emotional autonomy (F = 106.62, P = 0.001), reappraisal (F = 132.53, P = 0.001), and suppression (F = 50.94, P = 0.001). Moreover, between-group indices were as follows: F = 4.76 and P = 0.030, with an effect size of 0.21, for emotional autonomy, F = 8.17 and P = 0.001, with an effect size of 0.28, for reappraisal, and F = 30.66 and P = 0.001, with an effect size of 0.59, for suppression. These findings demonstrated a significant difference between the experimental and control groups in terms of dependent variables (i.e., emotional autonomy and emotion regulation).

| Variables and Sources | SS | df | MS | F | P-Value | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional autonomy | ||||||

| Time | 720.57 | 1.53 | 469.78 | 710.80 | 0.001 | 0.94 |

| Time × group | 216.17 | 3.06 | 70.46 | 106.62 | 0.001 | 0.83 |

| Group | 231.11 | 2 | 115.55 | 4.76 | 0.030 | 0.21 |

| Reappraisal | ||||||

| Time | 898.71 | 1.62 | 552.07 | 851.83 | 0.001 | 0.95 |

| Time × group | 279.64 | 3.25 | 85.89 | 132.53 | 0.001 | 0.86 |

| Group | 388.04 | 2 | 194.02 | 8.17 | 0.001 | 0.28 |

| Suppression | ||||||

| Time | 699.79 | 1.33 | 525.75 | 330.09 | 0.001 | 0.88 |

| Time × group | 215.40 | 2.50 | 86.17 | 50.94 | 0.001 | 0.70 |

| Group | 647.85 | 2 | 337.43 | 30.66 | 0.001 | 0.59 |

5. Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of EFT on the emotional autonomy and emotion regulation of students with depression symptoms. The study findings demonstrated the significant effectiveness of EFT in the emotional autonomy of students with depression symptoms. This finding is consistent with the results reported by some of the previous studies. For example, Tack et al. (33) reported that emotion-focused coping strategies affected the emotional autonomy of participants (34). The findings reported by Rodriguez-Gonzalez et al. (35) indicated that EFT encouraged autonomy in participants. In addition, Naderian et al. (34) showed the effectiveness of emotion-focused coping styles on self-acceptance, personal growth, and autonomy.

In other words, different aspects of emotional autonomy in adolescence before adulthood contradict attachment to parents (36). EFT causes satisfaction and reduces cognitive distortions in patients by fostering constructive interactions and identifying safe attachment styles (36). In other words, EFT is a therapeutic technique that focuses on the participation of emotions in long-term incompatible patterns. At the same time, autonomy is a crucial characteristic that marks the passage from childhood to adolescence (33); it involves developing relationships with parents, obtaining psychological intimacy in friendships, and achieving psychological intimacy in romantic relationships (25). In this sense, EFT aims to identify sensitive emotions and support individuals in safely evoking them. It is assumed that allowing these emotions to be processed in a secure environment leads to the development of fresher, healthier interaction patterns that reduce confusion and boost flexibility. An EFT therapist assists the client in changing the elements of destructive relationships. A more positive cycle emerges when the negative cycle is disrupted and responses begin to change (32).

The study results also showed the significant effect of EFT on reappraisal at the posttest and follow-up stages. This finding is consistent with the results reported by Asmari Bardezard et al. (37) who confirmed the effect of EFT on the difficulty of emotion regulation and acknowledged that EFT improves emotion self-regulation. In other words, the intrinsic and extrinsic processes known as emotions are in charge of regulating, assessing, and altering an individual's emotional responses when they get in the way of achieving their objectives. Consequently, any problems with the control of emotions can predispose a person to mental disorders (14). Different emotional regulation techniques are used by individuals to distinguish between healthy and unhealthy coping mechanisms (15). Emotionally focused therapy addresses unmet needs by altering patterns of emotional vulnerability or core pain and activating adaptive emotional responses like compassion and protective anger. Consistent with the findings of this study, the effectiveness of EFT was confirmed by Glisenti et al. (38) and Shahar (24) who stated that the therapeutic goals of EFT are predicated on the idea that changing a maladaptive emotion most effectively does not involve reason or skill acquisition. Instead, it occurs by triggering more adaptive emotions such as reappraisal. Generally speaking, how EFT affects emotion regulation appears to involve first identifying unhealthy and maladaptive emotions, and then, in order to restore normal functioning, attempting to modify and substitute unhealthy and maladaptive emotions with healthier and more adaptive ones.

Finally, the study results also revealed the significant effect of EFT on suppression at the posttest and follow-up stages. This finding is consistent with the results reported by Timulak et al. (23) and Glisenti et al. (38) who showed that EFT can affect depression symptoms by rebuilding dysfunctional emotions and replacing them with adaptive ones. In other words, maladaptive emotional challenges and problems make individuals with insecure attachment styles employ avoidant strategies in emotional situations. As a result, individuals with avoidant attachment styles use suppression mechanisms to restrict their exposure to emotional experiences (39). Emotion-oriented models seek to promote emotional awareness in order to replace experiential suppression and avoidance with adaptive strategies. Emotion acceptance, as opposed to emotion avoidance, is also the first step toward becoming aware of emotion. In addition, emotional acceptance accelerates the retrieval of suppressed content. Emotional self-regulation becomes an alternative to emotional avoidance and suppression when one is emotionally aware, which opens doors to touching repressed experiences (13). Emotionally focused therapy can realize this effort and help people overcome emotional issues and unfulfilled needs by altering unhealthy and maladaptive patterns of emotional coping through the activation of adaptive strategies (23).

Since this study was conducted on students of Ahvaz, the generalization of findings to other populations should be done cautiously. Another limitation of the present study was the lack of control over the socioeconomic backgrounds of the families.

5.1. Conclusions

The research findings suggested the positive effects of EFT on emotional autonomy and emotion regulation of students with depression symptoms. Therefore, educational counseling centers and psychological clinics are recommended to employ this treatment method to improve the psychological characteristics and emotion regulation of students with depression symptoms.