1. Background

diabetes is the most common form of diabetes, with over 90% of diabetic patients suffering from type 2 diabetes (1). The prevalence of type 2 diabetes is increasing globally (2). According to the International Diabetes Federation, 537 million adults (aged 20 - 79) are living with diabetes, and this number is projected to rise to 643 million by 2030 and 783 million by 2045 (3). This increase is largely attributed to lifestyle changes (2). With the rapid development of modern society, dietary patterns have shifted accordingly. Diets high in salt, fat, and sugar have contributed to the annual rise in diabetes cases, posing a significant threat to human health (4). Additionally, a strong family history of diabetes, age, obesity, and physical inactivity are factors that place patients at the highest risk (5).

Diabetes is a chronic, lifelong condition that leads to long-term damage and dysfunction of various organs, particularly the eyes, kidneys, heart, and blood vessels (6). Diabetes can reduce life expectancy by 5 to 15 percent, and the risk of mortality among patients with diabetes is twice as high as those without the condition (7). In 2021, diabetes was responsible for 6.7 million deaths worldwide (3). Beyond its medical challenges, this disease imposes a significant economic burden on patients and society. In 2021, diabetes, with a 316 percent increase over the past 15 years, accounted for at least $966 billion in healthcare costs (3). While the financial costs of diabetes are often visible, the emotional, psychological, social, and indirect costs associated with the disease are less frequently discussed. Patients with diabetes often experience substantial psychological distress due to the long-term demands and complications of the disease (8). To prevent complications and mortality related to diabetes, there is a critical need for specific self-care behaviors in various domains, including food choices, physical activity, appropriate medication use, and blood glucose monitoring (9). These behaviors are carried out by the patients themselves and constitute an essential and foundational requirement for managing type 2 diabetes (10).

Poor knowledge about the disease, delayed diagnosis, inadequate adherence to self-care behaviors, and the prescription of harmful alternative medications are significant challenges in treating type 2 diabetes (11). To control this disease, prevent adverse outcomes, and improve the functioning of patients with diabetes, self-care education plays a decisive role. This underscores the critical need to thoroughly investigate the barriers to self-care practices and to design and implement interventions aimed at enhancing self-care behaviors among patients with type 2 diabetes (12, 13).

Previous research has identified numerous barriers to diabetes self-care, particularly related to life circumstances, diabetes knowledge, family support, education provided by healthcare professionals, difficulties in changing dietary habits, economic challenges, fear, and struggles in adopting lifestyle changes. Steinman et al. highlighted limited time and resources for accessing medications, clinical support, and recommended guidelines for physical activity and healthy diets as significant barriers to self-care (14). Similarly, Alexandre et al. reported depression and the complexity of polypharmacy or medication regimens as major obstacles to self-care in their study (15). Patient experiences in these studies underscore the critical role of psychosocial factors in managing and coping with diabetes. These findings emphasize the need for integrated care that addresses psychosocial aspects by healthcare providers and behavioral health specialists, which may lead to enhanced self-care practices and minimized barriers (16).

In diabetes, the patient plays a pivotal role, as optimal treatment cannot be achieved without the individual's accountability and self-management (17). Research has consistently highlighted the undeniable importance of self-care in controlling diabetes and reducing its complications (15, 17, 18). However, despite the critical necessity and significance of self-care in managing this disease, the level of self-care among patients with diabetes remains low (18, 19). Therefore, identifying the factors that hinder self-care in diabetic patients is essential.

Most studies investigating barriers to self-care have been conducted outside of Iran, and research in this area within the country is limited, with the majority of studies adopting a quantitative approach. Consequently, there is a need for deeper insight into the challenges faced by patients with diabetes in practicing self-care.

2. Objectives

This study, using a qualitative approach, sought to identify the factors and difficulties experienced by diabetic patients in self-care. By uncovering these barriers, appropriate interventions and strategies can be developed to reduce these obstacles and promote self-care practices.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

Based on its objective, the present study is an applied research project and, in terms of methodology, falls under qualitative research of the phenomenological type. Study participants were patients with type 2 diabetes who were diagnosed by an endocrinologist and metabolism specialist and visited the diabetes outpatient clinic in Sanandaj, Iran, between October and November 2024. Before the interviews were carried out, written informed consent was obtained, and the data collection took place either at a diabetes outpatient clinic or at the Diabetes Association of Sanandaj. Sampling in this study was conducted using a purposive sampling method. The inclusion criteria for participants were as follows: Age over 30, having been diagnosed with diabetes for at least one year, currently undergoing treatment, and willingness to participate in an interview with the researcher. The exclusion criteria included a lack of honesty or refusal to answer certain questions.

3.2. Data Collection

Data collection was carried out using semi-structured interviews. To develop the interview questions and ensure their content validity, the overall framework of the semi-structured interview was initially prepared by summarizing the opinions of experts familiar with the topic. The main focus of the interview questions was to explore factors influencing self-care and the barriers to self-care. The duration of each interview, depending on the conditions, necessary time, participants' tolerance, and interest, ranged between 40 and 60 minutes. All interviews were conducted with the participants' consent and were audio-recorded. Subsequently, for further analysis, the interviews were meticulously transcribed into Word documents. For each participant, significant phrases and sentences directly related to their experiences were extracted, and meanings were formulated from these to fit within the framework of themes related to barriers to self-care. After the complete extraction of themes, the interviewer revisited some patients randomly to verify the validity of the extracted themes.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were represented using mean and standard deviation, while categorical variables were expressed through frequency and percentage. For data analysis, Clarke and Braun's (2006) coding method was applied, with the assistance of MAXQDA 2020 software.

4. Results

Out of forty-five patients with diabetes who were invited to the interview, 27 patients with illness durations ranging from 1 to 30 years participated in the interviews (response rate 60%). According to Table 1, the mean age of the participants was 51.5 (9.61%), ranging from 35 to 70 years. The majority of participants were female (n = 16, 59.3%). Regarding employment and marital status, most respondents were housekeepers (n = 11, 40.7%) and married (n = 24, 88.9%). Also, the most common educational level was elementary school (n = 8, 29.6%). Other characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 16 (59.3) |

| Male | 11 (40.7) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 24 (88.9) |

| Divorced/widowed | 3 (11.1) |

| Educational level | |

| Illiterate | 2 (7.4) |

| Elementary school | 8 (29.6) |

| Middle school | 6 (22.2) |

| Diploma | 7 (25.9) |

| Academic | 4 (14.8) |

| Employment status | |

| Secretary | 3 (11.1) |

| Housekeeper | 11 (40.7) |

| Driver | 3 (11.1) |

| Retired | 5 (18.5) |

| Self-employment | 5 (18.5) |

| Age (y) | 51.5 ± 9.61 |

| Weight (g) | 74.15 ± 12.88 |

| Height (cm) | 167.45 ± 7.21 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.40 ± 3.91 |

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

Data analysis led to the identification of 18 secondary codes as barriers to self-care, which are presented in Appendix 1 in Supplementary File.

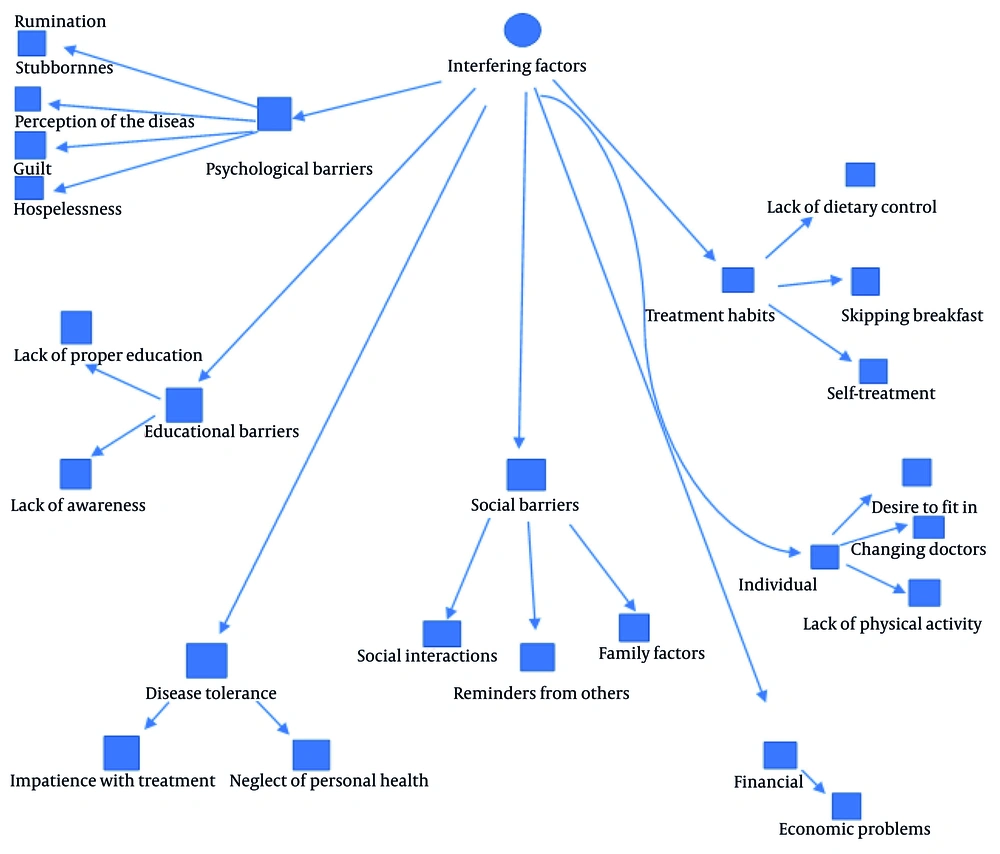

Appendix 1 in Supplementary File illustrates the interfering factors in the self-care patterns of diabetic patients. These factors create barriers that prevent diabetic patients from effectively practicing self-care. This set of factors hinders patients from taking care of themselves against the disease, thereby interfering with their self-care practices and leading to reduced self-care. Based on the analysis of interview coding, out of a total of 425 initial codes extracted, 208 initial codes were categorized as barriers to self-care. In the secondary coding stage, these 208 initial codes were grouped into 18 secondary codes, including economic problems, lack of awareness, inadequate education, stubbornness, perception of the disease, rumination, guilt, hopelessness, family factors, reminders from others, negligence, impatience with treatment, changing doctors, lack of physical activity, desire to fit in, self-treatment, lack of dietary control, and skipping breakfast. Finally, in the axial coding stage, the interfering factors were categorized into seven core codes: Financial barriers, educational barriers, psychological barriers, social barriers, disease tolerance, individual barriers, and dietary and treatment habits.

Based on the hierarchical diagram of interfering factors in the self-care model, seven core codes were identified: Psychological barriers, including secondary codes such as guilt, perception of the disease, hopelessness, and stubbornness; educational barriers, comprising secondary codes like lack of proper education and lack of awareness; disease tolerance, with secondary codes such as impatience with continuing treatment and neglect of personal health; social barriers, including secondary codes like family factors, reminders from others, and social interactions; financial barriers, with secondary codes such as socio-economic problems; individual barriers, consisting of secondary codes like changing doctors, the desire to fit in, and lack of physical activity; and treatment and dietary habits, formed by secondary codes such as lack of dietary control, skipping breakfast, and self-treatment. The barriers to self-care are presented in Figure 1.

5. Discussion

The present study aimed to identify the barriers to self-care in patients with type 2 diabetes in the city of Sanandaj. In this study, a total of five categories of barriers related to self-care in type 2 diabetes were identified, which include: Financial barriers, educational barriers, psychological barriers, individual barriers, and social barriers. The results of this study are consistent with the research conducted by Nam et al., who reviewed 1,454 studies published between 1990 and 2009, focusing on patient barriers, physician barriers, and self-management, and examined the barriers to self-care in patients with type 2 diabetes (16).

Financial barriers were one of the most significant obstacles reported by patients in this study. Some patients mentioned that due to financial difficulties, they do not regularly visit a doctor for check-ups, and many of them could not adhere to a diabetic diet because of economic issues. Previous research supports these findings.

Lack of awareness and knowledge about diabetes self-management methods has been reported as a barrier to diabetes self-management. This study revealed that most participants had superficial knowledge of diabetes self-care and lacked sufficient information about the complications of their disease. Patients identified lack of awareness about how to practice self-care and insufficient understanding of the disease as barriers to self-care. During the interviews, patients mentioned not receiving adequate education or training about the disease, its complications, and how to manage self-care. Previous studies support these findings, indicating that lack of knowledge is a significant barrier to self-care in patients with diabetes.

Most patients with type 2 diabetes receive limited support from their social networks. The lack of family support for diabetes management is a significant barrier to diabetes self-management. This study revealed that inappropriate behavior from those around them, viewing the disease as a cultural stigma, and actions such as constant reminders or inappropriate interactions make self-care more challenging for patients with diabetes. The importance of social relationships, whether as a barrier or a facilitator, has been demonstrated in previous research.

At the individual level, this study identified lack of dietary control, irregular meals, self-treatment and herbal remedies, the desire to fit in with others, changing doctors, and lack of physical activity as barriers. Some patients, influenced by non-specialists, used certain herbs as alternative treatments. Additionally, the relationship between doctors and patients with diabetes has both positive and negative impacts on diabetes self-management practices. Some patients changed their doctors due to a lack of comprehensive counseling and uncontrolled disease, which in turn disrupted their continuity of self-care. These findings align with the results of previous studies (17, 20).

Cravings for food and certain snacks, along with a lack of control, were among the challenges faced by patients with diabetes in maintaining an appropriate diet for self-management. Additionally, the eating behaviors of others can influence the dietary habits of patients with diabetes. In this study, several participants expressed that they did not want to eat differently from others, especially during social gatherings, as they wished to blend in with the group. Previous research supports this finding (13, 18).

In addition to the aforementioned factors, another crucial element in controlling diabetes and reducing its complications is physical activity. Our study revealed that patients with diabetes have limited physical activity, which is often attributed to a lack of time and physical health issues. Previous studies also support this finding.

Another barrier to self-care identified in this study is psychological factors. Previous research has also highlighted the role of psychological factors in self-care behaviors (20, 21). Living with diabetes increases the overall stress levels of patients with diabetes. This negative effect, resulting from adapting to new conditions and the demands of diabetes, is known as diabetes distress. Diabetes distress refers to the worries, doubts, fears, and threats associated with coping with diabetes, its complications, and its management. This distress is common among patients with diabetes and affects various aspects of diabetes self-care, often leading to lower levels of self-care, poorer emotional well-being, and worse metabolic outcomes (22, 23). In this study, hopelessness, rumination, guilt, impatience, neglect, stubbornness, and the perception that patients with diabetes have of their disease were identified as psychological barriers to self-care. The results of this study are consistent with previous research (24). Additionally, Skinner demonstrated in his research that stress, anxiety, and depression are significant barriers to self-care in patients with diabetes (22).

These findings highlight the need for advancements in the comprehensive healthcare system for diabetes. Given that self-care behaviors play a crucial role in controlling and reducing the complications of diabetes, it is essential to implement appropriate interventions to promote these behaviors. This, first and foremost, requires identifying the factors influencing self-care behaviors, followed by designing interventions that take these factors into account. One of the limitations of the current study is that self-care practices were not examined in relation to educational backgrounds and the duration of the disease.

Due to the use of purposive sampling methods, the findings of this study cannot be generalized to the broader population of diabetic patients. Therefore, it is recommended that similar studies be conducted in different centers, where referred patients come from diverse social and economic backgrounds. Additionally, further research is suggested to explore the factors influencing self-care behaviors among patients with type 2 diabetes.

5.1. Conclusions

This study has highlighted several barriers in self-care management for Iranian patients with type 2 diabetes, particularly related to economic, educational, social, individual, and psychological factors. These findings offer valuable insights that can contribute to the improvement of diabetes self-management education programs tailored to this population.