1. Background

Current humanitarian crises have mainly involved civil wars or natural disasters on a large scale. Such disasters not only affect the physical security of populations, but also their mental health. A key challenge in this regard is to identify the cases that are psychologically disturbed and need help to avoid the aggravation of their conditions (1). Kermanshah province is an important region in Iran, which has long been a strategic area in the Kurdistan region of Iran. The province is diverse in terms of cultural, social, and geographical conditions, with a variety of cultures, languages, dialects, religions, and climatic conditions in small scale (2).

Kermanshah has experienced a period of war between Iran and Iraq and affected more profoundly compared to the other provinces of Iran. In the autumn of 2017, most of the western cities in Kermanshah province experienced an earthquake with the magnitude of 7.3 (3, 4). Despite the significant impact of the disaster on the mental health of the population in this area, few studies have been focused on the mental health effects of the earthquake. To date, limited studies have systematically addressed the psychological consequences of earthquakes (5-7).

According to the findings regarding the mental health of the survivors of earthquakes and other natural and man-made crises among the Kurdish population in Kermanshah province, the researchers have only utilized the western instruments that have been translated into Persian to evaluate the associated trauma and other disorders. However, no Kurdish instruments appropriate to the culture of this region have been employed (8). Therefore, it is essential to translate and implement the major versions of these tools to assess trauma and the subsequent disorders using the native languages of the affected victims due to the inevitable differences in linguistic and semantic aspects. The use of normative tools based on language and culture could increase the ability to detect and separate healthy and injured individuals (9, 10).

In the past decades, a wide range of evaluation and screening tools have been employed for traumas and the associated symptoms, including self-report questionnaires and various interview methods (11, 12). The post-traumatic stress disorders checklist (PCL) is a self-monitoring tool used for the measurement of PTSD symptoms in clinical and research fields (13). Recently, the PCL has been updated in accordance with the new diagnostic criteria for PTSD in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (14). The PCL contains 17 items, which are scored based on a five-point Likert scale within the score range of 1 - 85. The cutoff point of PTSD diagnosis in the PCL scoreboard checklists has been proposed at the score of 50, while validation studies have proposed different scores of 38 - 47 for the PTSD to meet the DSM criteria (15-17). The findings of validation studies have indicated that the desired cutoff point depends on the field, population, and other demographic characteristics.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the PCL and its ability to be recognized as a screening tool. Furthermore, we aimed to determine the appropriate cutoff point with the optimal balance of sensitivity and specificity for the Kurdish population affected by the earthquake with the magnitude of 7.3 in the autumn of 2017 in Kermanshah. For various reasons, conducting this research was far more complex than the translation of a psychometric tool and its standardization for different western populations, and the standards of western research cannot be applied to such studies. The most obvious issue in this regard is that the populations in the west of Iran speak different languages and dialects, and it is impossible to define a single language or dialect for the entire Kermanshah province. In addition, the people in these areas consider Kurdish to be their native language for writing, reading, and speaking, while Persian is primarily considered as the language officially recognized by the government and educational system in Iran. Meanwhile, due to some environmental factors, some people do not have a culture that is reluctant to use a particular language. Therefore, the use of Kurdish scales was essential to the better diagnosis of the symptoms of mental disorders in the individuals affected by earthquake in the present study and assessment of mental disorders.

3. Methods

This cross-sectional study was performed to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of the PCL. The subjects were selected via purposive sampling from the survivors of Kermanshah earthquake in the communities and camps in Javanrud and Salas counties, who referred to the counseling centers of these cities during March-September 2018.

The sample population was selected by referring to the sites and camps of the earthquake survivors of Javanrud and Salas cities, and 200 individuals were selected and provided with the psychological triage for PTSD diagnosis to enter the study. Due to the lack of reliable census data on the earthquake survivors, random cluster sampling was used based on the division of the cities into neighborhoods and camps.

Local interviewers visited the survivor camps and neighborhood, where they randomly sampled the individuals and families willing to cooperate in the research. Informed consent was obtained from the selected participants regarding the research objectives, confidentiality terms, potential hazards, discomforts, exclusion, benefits, and information protection.

3.1. Research Tools

In addition to a demographic questionnaire, data were collected using the PCL and Mississippi scale for PTSD. The PCL is a self-monitoring instrument used to measure disturbances and distinguish the patients with PTSD symptoms from healthy individuals, as well as other patients as a diagnostic tool. The key advantage of the instrument is its shortness. The PCL was developed by Weathers et al. in 1994 based on the DSM diagnostic criteria for the National Center for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in the United States. The PCL consists of 17 items, five of which measure the signs and symptoms of the recurrence of traumatic injury, seven items are focused on the signs and symptoms of numbness and emotional avoidance, and five items measure the severe signs and symptoms of excitation. The items in the PCL are scored within the range of 17 - 85, and the total score could be obtained by summing up the scores of the 17 expressions based on a five-point Likert scale (not at all = 1, very low = 2, average = 3, high = 4, very high = 5). The cutoff point for PTSD recognition is 50 (14).

Similar tools have also been developed and adapted based on the recommended methods in intercultural research (18). In the present study, the PCL was translated into Kurdish in accordance with the instructions of van Ommeren et al. (19), which include vocabulary translation, blind translation, and group discussions with local bilingual experts and some of the participants in order to ensure that the universal translation is equivalent to semantics. In the pilot project of the mentioned study, the internal consistency coefficients of 0.97 and 0.93 were estimated for the entire scale and testing of the tool within a week, respectively. In addition, the convergent validity between the scale and Mississippi disaster stress disorder was reported to be 0.96, and the cutoff point 50 was determined to be optimal for the prediction of PTSD diagnosis. In Iran, the reliability and validity of the scale have been evaluated by Goudarzi (2003) at Shiraz University using the data obtained from the implementation of the scale on 117 subjects, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of has been reported to be 0.93, confirming the validity. In addition, the validity coefficient of the scale has been estimated at 0.87 using the polygons.

The Mississippi PTSD questionnaire is a self-report scale developed by Kian et al. (1988) to assess the severity of PTSD symptoms. The scale has 35 items, which are scored based on a five-point scale (1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively), and the total score is calculated within the range of 35 - 175, with the scores ≥ 107 showing the presence of PTSD in the respondent.

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the scale has been reported to be 0.86 - 0.94, which indicates high validity and a good correlation with the other instruments used for the measurement of PTSD. Moreover, the simultaneous validity of the scale with the three tools of the lifestyle list, PTSD index, and Padua’s log has been reported to be 23.0, 82.0, and 75.0, respectively (5).

Data analysis was performed in SPSS version 24.0. The internal consistency of the total PCL score and the sub-scores were determined using the Cronbach’s alpha, and the reliability and validity of the total score of the PCL symptoms and subclass scores were calculated using Pearson’s correlation-coefficient. In addition, the sensitivity and specificity coefficients were used to determine the PCL detection capability (20). The receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) was also used to determine the cutoff point and precision of the tool. The optimal cutoff point from the proposed points was determined using the Youden’s index. At the cutoff point, the diagnostic value parameters of the P-CDR tool included sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, negative likelihood ratio, positive likelihood ratio, overall diagnostic accuracy, and diagnostic odds ratio, and the range of each parameter was estimated at 95% confidence interval. In all the statistical analyses, the significance level was considered at 0.05. In total, the data of 200 survivors of the earthquake in Kermanshah were analyzed, and the demographic characteristics of the sample population are presented in Table 1.

| Variable | Values, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 102 (50.5) |

| Female | 98 (49.5) |

| Religious | |

| Islam (Sunee) | 154 (77) |

| Islam (Sheea) | 7 (14) |

| Izadi | 32 (16) |

| Language | |

| Kurdish (Jafi) | 162 (82) |

| Kurdish (Kalhor) | 24 (12) |

| Others | 14 (7) |

| Education | |

| Uneducated | 54 (27) |

| Under diploma | 120 (60) |

| Upper diploma | 26 (13) |

| Job | |

| Housewife | 91 (45.5) |

| Unemployed | 37 (18.5) |

| Students | 10 (5) |

| Personal Jobs | 40 (20) |

| Employed jobs | 22 (11) |

3.2. Internal Consistency

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the PCL scores in the study group was calculated (α = 0.85), indicating the well-documented validity of the scale (Table 2). In addition, the validity coefficients of the subscales of symptoms of recurrent trauma, emotional numbness, negative changes in knowledge and creativity, and arousal were estimated at 76%, 88%, 74%, and 71%, respectively.

| No | Kurdish Items of PCL Checklist | Mean | Std. Deviation | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Repeated, disturbing memories, thoughts, or images of a stressful experience from the past? | 3.359 | 0.845 | 0.453 | 0.861 |

| 2 | Repeated, disturbing dreams of a stressful experience from the past? | 4.016 | 1.694 | 0.607 | 0.860 |

| 3 | Suddenly acting or feeling as if a stressful experience were happening again (as if you were reliving it)? | 3.850 | 0.784 | 0.455 | 0.850 |

| 4 | Feeling very upset when something reminded you of a stressful experience from the past? | 4.065 | 1.512 | 0.635 | 0.861 |

| 5 | Having physical reactions (e.g., heart pounding, trouble breathing, or sweating) when something reminded you of a stressful experience from the past? | 3.974 | 1.401 | 0.170 | 0.860 |

| 6 | Avoid thinking about or talking about a stressful experience from the past or avoid having feelings related to it? | 2.521 | 1.691 | 0.339 | 0.860 |

| 7 | Avoid activities or situations because they remind you of a stressful experience from the past? | 3.772 | 1.031 | 0.519 | 0.851 |

| 8 | Trouble remembering important parts of a stressful experience from the past? | 3.777 | 1.981 | 0.393 | 0.860 |

| 9 | Loss of interest in things that you used to enjoy? | 3.569 | 0.567 | 0.433 | 0.860 |

| 10 | Feeling distant or cut off from other people? | 3.526 | 1.233 | 0.620 | 0.851 |

| 11 | Feeling emotionally numb or being unable to have loving feelings for those close to you? | 3.521 | 1.231 | 0.687 | 0.860 |

| 12 | Feeling as if your future will somehow be cut short? | 3.344 | 1.593 | 0.601 | 0.860 |

| 13 | Trouble falling or staying asleep? | 3.559 | 1.777 | 0.601 | 0.861 |

| 14 | Feeling irritable or having angry outbursts? | 3.369 | 0.045 | 0.409 | 0.860 |

| 15 | Having difficulty concentrating? | 2.093 | 1.691 | 0.375 | 0.860 |

| 16 | Being “super alert” or watchful on guard? | 3.387 | 1.011 | 0.432 | 0.851 |

| 17 | Feeling jumpy or easily startled? | 3.865 | 1.211 | 0.534 | 0.850 |

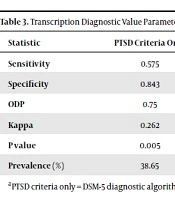

The underlying curve of the PCL instrument was estimated at 968.0, with the standard error of 012.0 (P ≤ 0.001), and the cutoff point of 50 was considered optimal for the PCL. According to the information in Table 2, the PCL reached the highest level of sensitivity, properties, and Kappa-Cohen values at the cutoff point of 50 (Table 3). Only in the PTSD criteria, the DSM-5 diagnostic algorithm for PTSD shows the ODP overall diagnostic power, with the cutoff point of 50 as the initial cutoff point (14).

| Statistic | PTSD Criteria Only | Cutoff Score = 50 | Cutoff Score = 52 | Cutoff Score = 53 | Cutoff Score = 55 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 0.575 | 0.48 | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.61 |

| Specificity | 0.843 | 0.857 | 0.77 | 0.71 | 0.80 |

| ODP | 0.75 | 0.70 | 0.73 | 0.69 | 0.74 |

| Kappa | 0.262 | 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.49 |

| P value | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Prevalence (%) | 38.65 | 41.73 | 64.31 | 62.27 | 63.17 |

aPTSD criteria only = DSM-5 diagnostic algorithm for PTSD. ODP overall diagnostic power. Cutoff score of 50 is an initial cutoff score (14)

3.3. Convergent Validity

In the present study, planned comparison was performed to determine the convergent validity of the PCL and Mississippi scale for combat-related PTSD (M-PTSD). According to the information in Table 4 regarding convergent validity, positive correlations were observed between the PCL and M-PTSD items (range = 0.40 - 0.49) (14), indicating that the PCL had acceptable convergent validity and could particularly discriminate PTSD patients from healthy individuals and other patients.

4. Results and Discussion

The present study aimed to evaluate the validity, reliability, and accuracy of the diagnosis of PTSD using the PCL in the survivors of the earthquake of Kermanshah in 2017. The ROC curve analysis indicated that score 23 was the optimal cutoff point for the checklist of the diagnosis of PTSD symptoms from other patients based on the total diagnostic power, sensitivity, and specificity, which is consistent with the previous studies in this regard (15, 21, 22). The internal consistency of the checklist was estimated to be α = 0.85, which indicated the reliability of the checklist. In addition, the convergent validity of the PCL was positively correlated with the items of the M-PTSD, which is in line with the previous findings regarding trauma (23).

Our findings are partially consistent with the prior studies regarding the validity and reliability of the PCL as the estimated cutoff points were lower compared to the previous validation studies. In a study by Bovin et al., the cutoff point of 51 was reported to be optimal for the PCL. In addition, Bluel et al. (2015) assessed the psychometric properties of the PCL in undergraduate students, stating that the PCL had high sensitivity and performance and significant features at the cutoff point of 57 (15). Similarly, Satura et al. (2016) assessed the psychometric properties of the English and French versions of the PCL in undergraduate students, setting 51 as the appropriate cutoff point for the scale (24).

According to the results of the present study, the PCL and calculated cutoff point had proper psychological characteristics as a screening tool for the identification of PTSD symptoms in the survivors of Kermanshah earthquake. However, the psychometric values obtained in the evaluations (e.g., sensitivity) were slightly lower compared to the reported values in the previous validation studies. Compared to the other validation and validation studies, although no precise tools were available for the interview, the method could ultimately reduce the reliability of the research, which in turn decreased its sensitivity and properties; however, since the validation interviews were conducted by experts with Kurdish educational and cultural backgrounds, the symptoms of mental disorders could be assessed accurately, which resulted in the better understanding of the crisis in the subjects.

Our findings were limited to the validity and reliability of the PTSD syllable (PCL) checklist for the survivors of the earthquake in Kermanshah in 2017. Although the methods used to achieve this goal are completely scientific, the research instrument should be complemented by other means; for instance, in addition to clinical interviews and predictive variables, future studies should examine the structural and confirmatory factor analysis of the PCL in larger sample sizes throughout various dialects of the Kurdish language.

4.1. Conclusion

In this study, the psychometric and diagnostic properties of the Kurdish version of the PCL screening tool for PTSD were presented. This was the first valid study in the language of an Iranian population affected by a natural disaster, and the findings could lay the groundwork for further investigations regarding mental health and trauma in the Kurdish population of the survivors of the earthquake in Kermanshah, while the applied research tool could be used for the screening of the individuals with PTSD by psychologists, counselors, and local mental health authorities.