1. Context

The drive for the realization of sustainable development goals constitutes the hub of major policies of the present and immediate past political dispensation in Nigeria. The focus on welfare improvement reflects on key policies and programs adopted in Nigeria. The pursuit of growth plans has necessitated the adoption of programs that could improve the living conditions of the populace, including access to healthcare services. One notable initiative of international repute that focuses on improving the health performance of developing countries is the Universal Health Coverage (UHC) which constitutes an essential aspect of the sustainable development goals (1).

In 2014, the presidential summit on Universal Health Coverage held in Nigeria, recognized that health is a fundamental human right and the responsibility of the government in assuring good health for its people; and that UHC holds the key to unlocking the door for equitable, qualitative and universally accessible healthcare for all Nigerians without suffering financial hardship. The key challenges for achieving UHC in Nigeria are related to the sub-optimal health system characterized by budgetary constraints, inadequate financial protection for the poor, shortage and mal-distribution of human resources for health, uneven quality of health care services, and the challenges in the provision of health commodities, includes poor coordination, and weak referral system and the uneven utilization of health services (2).

A key aspect to achieving the UHC by 2030 in Nigeria is to intensify government spending on health relative to the total economy - namely, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (3). This measure is most appropriate target in the context of UHC goals and the right to health for several reasons. This measure takes account of affordability within a specific country context as the health expenditure target is expressed relative to the country’s level of economic activity (3). It thus follows that government financing, budgetary allocation and expenditure are essential in appraising prospects of realizing UHC goals in Nigeria. This article attempts an expository discuss on the performance of Nigeria towards achieving UHC. It will evaluate and appraise government health budgetary allocations, finance, and health care expenditure to ascertain prospects of realizing the goals of the UHC as expressed.

2. Evidence Acquisition

Data sources for this publication include journal articles, reports and other secondary sources. Documents reviewed provided information on health care financing in Nigeria. Searches were conducted in PubMed, Google Scholar, and WHO Library Database with the following search terms “healthcare financing Nigeria”, “health budget allocation Nigeria”, “government health financing policies Nigeria” and “health expenditure Nigeria”. Further publications were identified through snowballing from references cited in relevant articles and reports. We reviewed only papers written in English with no date restrictions placed on searches.

3. Healthcare Budgetary Allocation in Nigeria

Health care financing system can be referred to the process by which revenues are collected from various sources which can either be primary or secondary and include out-of-pocket payments (OOPs), taxes (indirect and direct), funding from donor, co-payment, health investments, voluntary prepayments, mandatory prepayment, which are accumulated in fund pools (4-6). The pattern of health financing is closely related to the provision of services and helps determine a system’s ability to achieve universal health coverage and socioeconomic development. These strategies also determine the structure and quality of health outcomes achieved by any health system (7). The way a country finances its health care system is an essential determining factor for achieving UHC because a good healthcare financing strategy should offer adequate financial protection so that no household suffers from a burden of financial expenses (4).

An important aim of UHC is to ensure that all have sufficient access to healthcare needs without significant OOPs at the point of obtaining care (8, 9). This is usually achieved by risk pooling through tax funded or Social Health Insurance (SHI) schemes (8, 10). In Nigeria, healthcare financing revenue is mainly obtained from pooled and un pooled sources. The pooled sources are raised from direct and indirect taxation, budgetary allocation, and donor funding (4). However, the un-pooled sources which include OOPs in the forms of payment for medical products and services contribute over 70% of total health expenditure (4). This extreme reliance on OOPs creates a significant barrier to health services access and leaves a large percentage of the population running the risk of impoverishment (11), as OOPs above 40% is deemed catastrophic health payment (12). Due to this, Nigeria faces a disproportionate distribution in health system financing (13). Over the years, healthcare financing in Nigeria has been described as inadequate with budgetary allocation to health barely exceeding 7% of the nation’s total budget (Table 1). This allocation clearly falls below the April 2001 Abuja declaration of allocating a minimum of 15% of national budget to health (4, 13, 14).

| Year | Total National Budget (NGN Billion) | Total Health Budget (Federal Government) (NGN Billion) | % Health Budget | 15% of Total Budget (NGN Billion) | Gaps (Amount Needed to Meet Abuja Declaration of 2001 (15% Of Budget Size) (NGN Billion) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 4695.19 | 339.38 | 7.23 | 704.28 | 364.90 |

| 2015 | 5067.90 | 347.26 | 6.85 | 760.19 | 412.93 |

| 2016 | 6060.48 | 353.54 | 5.83 | 909.07 | 555.53 |

| 2017 | 7441.18 | 380.16 | 5.11 | 1116.18 | 736.02 |

| 2018 | 9120.33 | 528.14 | 5.79 | 1368.05 | 839.91 |

| 2019 | 8830.00 | 372.70 | 4.22 | 1324.50 | 951.80 |

| 2020 | 10594.36 | 463.80 | 4.38 | 1589.15 | 1125.35 |

| NGN 4.99 trillion |

In a report released by WHO in 2011, Nigeria and 26 other countries were listed under the category of insufficient progress towards Abuja Declaration while only 3 countries were listed as on track with respect to the health Millennium Development Goals (14). Furthermore, there is an uneven allocation of finance and facilities in the three tiers of healthcare system in Nigeria i.e. primary, secondary, and tertiary health care. In addition, the inadequate budgetary provision for health has resulted in the lack of adequate manpower and facilities to provide quality care for the citizens. Moreover, there is an obvious deficiency in the number of these facilities which has significantly affected healthcare provision (15). For instance, for TB, the financial burden imposed by OOPs often discourage treatment adherence resulting into poor outcome with impact on country’s economy (16). By 2013, only five of the African Union countries have been able to meet the target of the Abuja declaration including Rwanda, Botswana, Zambia, Togo, and Madagascar (17, 18). Swaziland was able to meet the Abuja target by 2015 with South Africa also nearing the target at 14% (19), both countries alongside Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, Malawi, Mozambique, Seychelles and Tanzania are also able to keep OOPs below 20% (18).

An evaluation of the table reveals notable variations in the health sector budgetary allocation between 2014 and 2020. In 2014, only 7.23% of the Federal Government’s NGN4.695 trillion budget was earmarked for the health sector. The years 2015 and 2016 revealed a notable decline. In 2015, the allocation to the health sector was NGN 347.26 billion (6.85%) of the budget which is comparatively lower than the 2014 threshold. In 2016, 2017 and 2018, health sector allocation compared to the Federal Government’s expenditure size was determined to be 5.83%, 5.11% and 5.79% respectively. It is important to note that since the post-Millennium Development Goals era (2016 till date), the healthcare budgetary allocations have always fallen below the 15% of the national budget allocation.

The healthcare budget for the year 2018 had a significant boost as a result of the increased allocation to the Ministry of Health and the release of NGN55.15 billion by the National Assembly for the implementation of the National Health Act which was passed in 2014. Furthermore, in 2019 and 2020, the health budget fell below 5% which reflects a decline in health expenditure compared to previous years. From our analysis, if the Abuja declaration was implemented, additional allocations of NGN 4.99 trillion, approximately 13 Billion USD as of 5 June 2020, should have been injected into the health sector between 2014 and 2020. The inadequate budgetary allocation for healthcare has significantly influenced recurrent and capital health expenditure. It is worthy to note that the insufficient allocation will significantly affect capital expenditure which is a large determinant of the development of any health system.

4. Health Care Expenditure in Nigeria

There is a growing international focus on the need for adequate domestic government spending on a range of social services and the health sector attracts major focus in recent times (3), especially in low-and-middle-income countries under which Nigeria is categorized. The rationale behind this contemporary focus is captured in the core objectives of the universal health coverage. The United Nations System Task Team on the Post-2015 United Nations Development Agenda noted that “Ensuring people’s rights to health and education, including through universal access to quality health and education services, is vital for inclusive social development” and this requires investment to “close the gaps in human capabilities that help perpetuate inequalities and poverty across generations” (20). The universal health coverage initiative is a strong drive towards achieving United Nations development Agenda as expressed. As Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 3.8) aptly stated, every country should be able to “achieve UHC including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines for all” (21).

Since, a key element of UHC includes financial protection from the costs of ill health and access to and use of needed health services within a country, reducing the reliance on out of pocket payments for health care is important for financial protection (22). This implies that government expenditure to the health sector is crucial in achieving financial protection. In fact, the 2010 World Health Report stated that: “It is only when direct payments fall to 15% - 20% of total health expenditures that the incidence of financial catastrophe and impoverishment fall to negligible levels” (8). Hence, government expenditure in Nigeria is crucial in the realization of UHC objectives of financial protection. By government expenditure, this paper captures domestic government general health expenditure as a percentage of the GDP expressed as: recurrent and capital spending from government (central and local) budgets, external borrowings and grants (including donations from international agencies and nongovernmental organizations), and social (or compulsory) health insurance funds, all as % of GDP (23).

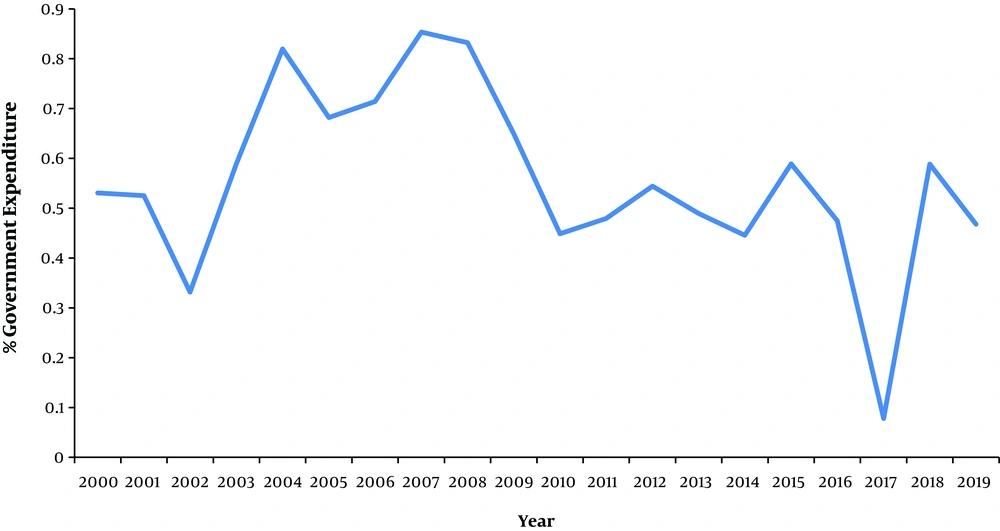

Specifically, in 2016, total government health expenditure was N588 billion (US$ 2.2 billion) or 0.47 percent of GDP (Figure 1), whereas governments are recommended to spend at least 5% of their GDP on health in order to truly progress towards UHC (3). As a share of total government expenditure, government health spending was also low at 6.1 percent amounting to just US$ 11 per capita - well below regional and lower middle-income averages and the recommended US$ 86 per capita low- and middle-income country benchmark needed to deliver a limited set of key health services (3, 23).

Figure 1 shows the trend of government expenditure for the period highlighted. Interestingly, within the period of 2007 - 2008 the increase in government expenditure was remarkable, it was valued at approximately 0.85% in 2007 and 0.83% in 2008. The GDP during these periods stood at NGN 42,922.41 billion and NGN 46,012.52 billion respectively. This period witnessed a significant upsurge of government expenditure on health by approximately 0.32% and 0.3% respectively as health.

Surprisingly, the fall in government health expenditure between the periods of 2014 to 2017 was significant. In 2015, government health expenditure was 0.58% at the GDP value of NGN 69,023.93 billion. This indicates the low expenditure profile recording for Nigeria at the onset of the SDGs initiative for Universal health coverage. Although there was a remarkable upward push of government spending between 2017 to 2018, the rise still falls below expectation as the GDP for the period was NGN 68,490.98 billion and NGN 69,810.02 billion with a target of 5% of the GDP for the realization of the UHC the rise is indeed not sufficient, with the decline in 2019 is indicated creates further concern.

In addition to the 2001 Abuja Declaration, the High-Level Task Force on Innovative Financing for Health Systems (HLTF) recommended that low income countries should allocate at least US$44 per capita to deliver an essential package of health services, with the countries in the African Union recognizing the importance of both the Abuja Declaration and the HLTF recommendations (18, 24, 25). Nigeria and 22 other countries have been able to achieve the Task Force recommendations and only Rwanda, Botswana and Zambia have been able to meet both targets (Table 2) (18).

| General Government Health Expenditure More than 15% | General Government Health Expenditure Less than 15% | |

|---|---|---|

| Total health expenditure per capita more than US$44 | Botswana, Rwanda, Zambia (3 countries) | Algeria, Angola, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Congo, Cote d’Ivoire, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Lesotho, Mauritius, Namibia, Nigeria, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Seychelles, South Africa, Swaziland, Uganda (20 countries) |

| Total health expenditure per capita less than US$44 | Madagascar, Togo (2 countries) | Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, DRC, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Guinea, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Niger, Sierra Leone, Tanzania (20 countries) |

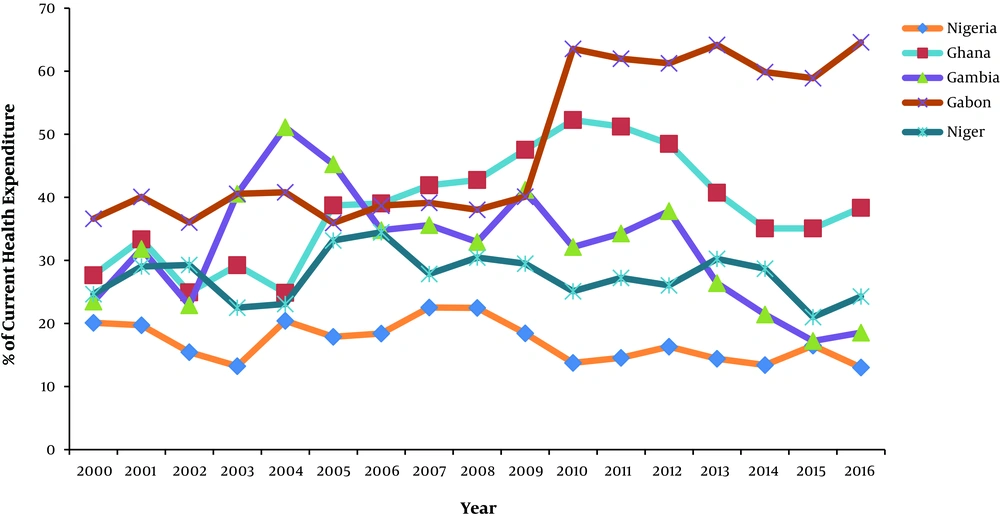

Nigeria also lags behind relative to some other low- and middle-income countries in terms of government expenditure to the health sector in achieving the Universal Health Coverage. Figure 2 gives credence to this assertion.

Figure 2 shows government health expenditure for five African countries 2000 - 2016. Government health expenditure in Nigeria as a percentage of current health expenditure is low relative to their African counterpart. From the graph, it is explicit that government allocation to health does not exceed 20% of the total health expenditure as expressed. This poor expenditure is quite worrisome as achieving UHC is heavily dependent on government efficient expenditure on health.

Health financing for UHC is often assessed by whether countries spend enough on health; and raising sufficient revenue for health is the first fundamental factor determining a country’s ability to deliver such basic health services. However, another important factor to consider is whether countries maximize their limited resources efficiently to improve health outcomes (26). From the forgoing, Nigeria health expenditure over the period under review is not sufficient enough to bolster confidence in realizing the goals of UHC, except robust allocations are made to the health sector, and efficient use of scarce resources is implemented, achieving UHC for Nigeria might be a mere mirage.

5. Impact of Healthcare Budgetary Allocation and Healthcare Expenditure on Health System Efficiency

The significant changes and trends in the budget and expenditure of the Nigerian healthcare system have significantly impacted health care indicators over the years. Mortality data are essential sources of demographic, geographic and cause-of-death statistics and can be used to quantify the efficiency of a health system, as well as to define and evaluate a country’s healthcare priorities (27). A 2018 Global burden of disease study from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (28) revealed trends in maternal mortality ratio per 100,000 live births, life expectancy, neonatal, infant and under-five mortality rates per 1,000 live births from the years 2008 to 2018. The years 2008 to 2011 saw the greatest improvements in neonatal, infant, and under-five mortality rates. However, this was followed by a steady decline from 2012 to 2016 and subsequent improvements between 2017 and 2018. On the contrary, life expectancy rates steadily increased from the years 2008 to 2018. Despite this improvement, the percentage increase gradually decreased over the years from 1.09% in 2008 to 0.71% in 2018. Studies have shown that a variable relationship exists between healthcare expenditure and health outcomes. A study in eight East African countries in 2017 revealed a strong, positive relationship between total healthcare expenditure and total life expectancy and a contrary relationship between health expenditure and neonatal, infant and under-five deaths (29).

A more recent study based on cross-sectional and annual time series data revealed that health expenditure had a significant effect on vital health indicators, and an increase in public health expenditure led to the improvement of life expectancy, infant and under-five mortality rates (30). Table 1 in this study reveals a steady decline in the percentage budgetary allocation and health expenditure from the year 2014 to 2017 with a slight increase in 2018. This decline between 2014 and 2017 correlated with decreasing progress in neonatal and infant mortality within this period and the progressive decline in the yearly improvement of life expectancy. Meanwhile, the improvement in these mortality data in the year 2018 rightly correlated with the increase in the healthcare budgetary allocation and expenditure. These trends demonstrate a positive relationship between health expenditure and mortality health indicators in Nigeria. Hence, there is a strong possibility that the efficiency of the health system has remained somewhat static over the years with health output directly linked to healthcare expenditure and, the declining health outcomes observed directly corresponding to the decrease in health care budgeting and expenditure.

Worthy of mention is coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) pandemic. COVID-19 is a global health threat and African countries including Nigeria are not spared from the threat (31). The incidence of the COVID-19 pandemic has also revealed current lapses in the Nigerian healthcare capacity. With 15,759 COVID-19 tests conducted, a current case fatality rate of 3% and a current laboratory testing capacity of 2500 persons per day, as of 30 May 2020 (32), there needs to be increased investment in healthcare to improve the diagnosis and management of COVID-19 and mitigate the impending favourable effects of the pandemic on the nation as a whole.

6. Health System Performance Variations in Relation to UHC

Realizing the goals of the UHC requires consistent policy formulation, and evaluation to ensure that the core aspect of the UHC is achieved. It is pertinent to state explicitly that service coverage and financial protection should constitute the bedrock of policy drive in attaining the goals of the UHC. The rational justification for this assertion is quite conspicuous because as highlighted by the 2019 World health organization report on health financing towards achieving the UHC (33), the definition of the UHC embodies two related objectives:

1. Equity in access to health services which implies the provision of quality health preventive and treatment care services as at when due to recipients without denial in assess, due to lack of health facility or health practitioners.

2. Financial protection which implies cost of assessing medical services, should not impact negatively on the recipients.

A critical aspect in the quest to achieve the goals of the UHC is increase in government spending on the health sector. Increasing government budget to the health sector in Nigeria will put the polity on the right track towards the objectives of the UHC. However, without a commensurate rise in required medical infrastructure and medical personnel, efforts towards realizing the goals of the UHC could be a mere mirage. Resources are scarce; hence the efficient utilization of allocated resources is fundamental to success. In capturing the importance of service coverage, it is crucial to expunge the essential components of service coverage.

According to the world health organization, achieving the goals of the UHC in terms of service coverage involves the following key elements: Availability of essential medicines and technologies to diagnose and treat medical problems and a sufficient capacity of well-trained, motivated health workers to provide the services to meet patients’ needs based on the best available evidence (34).

Furthermore, in a report on the UHC (35), the WHO made it quite explicit that primary health care is the most efficient and cost-effective way to achieve universal health coverage around the world. This is because primary health care serves as a first point of contact for patients at communal levels, thereby facilitating the realization of universal health care delivery. Primary health care delivery system in Nigeria is regulated by the local government authorities. They coordinate and examine the activities of health care delivery outlets to ensure best practice at all times. According to Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research (36), Nigeria still lags behind in allocating sufficient funding for primary health care services. This explains the reason for the deplorable conditions in some of the primary health facilities in Nigeria. The budget allocation has been on the decrease even after plans to push towards the UHC.

The report further enunciated that to meet the health workforce requirements of the Sustainable Development Goals and universal health coverage targets, over 18 million additional health workers are needed by 2030. Gaps in the supply of and demand for health workers are concentrated in resource-poor countries. The growing demand for health workers is projected to add an estimated 40 million health sector jobs to the global economy by 2030. Investments are needed from both public and private sectors in health worker education, as well as in the creation and filling of funded positions in the health sector and the health economy. It thus follows that increase in the number of medical practitioners and medical infrastructure is pertinent to achieving the goals of the UHC in Nigeria.

Another aspect in the quest to realize the goals of the UHC as previously highlighted is financial protection. According to WHO (33), in assessing countries progress towards the UHC, emphasis was made on strengthening health systems through robust financial structure. It was argued that when people have to pay for most of the cost of health services out of their own pockets, the poor are often unable to obtain many of the services they need and even the rich can be exposed to financial hardship in the event of severe or long term illnesses. Thus, pooling funds from compulsory funding sources such as mandatory health insurance contributions can help spread the financial risk. Thus, one of the major goals of the UHC is to mitigate the negative impact of health financial burden through a well structures health payment system. However, UHC does not mean free coverage for all possible intervention regardless of the cost as no country can provide free services sustainably.

While government expenditure accommodates 20% of the total health expenditure, the out-of-pocket finance sources dominates. This has implications towards the Nigerian case for efforts towards the UHC. The point to note here is financial protection has not been achieved as expected despite government budgetary allocations. The National Health Insurance scheme constitutes a major medium towards financial protection and equity in access towards the goals of the UHC. But according to the report from the national health account (37) the health insurance scheme in terms of coverage has very little impact. A significant number of individuals do not benefit from the health insurance scheme as most of them are not even aware, hence its impact towards financial protection towards the goal of the UHC is grossly insignificant (38).

7. Conclusion

The inadequate budgetary allocation to healthcare has significantly influenced recurrent and capital health expenditure. It is worthy to note that the insufficient allocation will continue to significantly affect capital expenditure which is a large determinant of the development of any health system. With the current state of healthcare budget allocation in Nigeria, efforts need to be intensified to ensure the achievement of Universal Health Coverage. In the face of achieving UHC, reviewing the system of healthcare financing and ensuring prudent allocation of resources while shifting the focus from out-of-pocket payments for health is essential. The government should also continue to strengthen the national health insurance scheme and extend its benefits to the informal sector. We recommend that political commitment to improving the health of the population should be prioritized to ensure health systems goals of efficiency, equity, quality of care, sustainability, financial risk protection for all citizens are achievable. The much-needed political commitment to ensuring efforts toward achieving UHC in other African Union member countries that are lagging behind in implementation of Abuja Declaration is also recommended.