1. Background

Diabetes is considered to be the most prevalent chronic disease across the world, and the increasing prevalence of the disease is a major health concern. The global prevalence of diabetes in 2011 was estimated to be 366 and 552 million, which is expected to further increase by 2030 (1, 2). In terms of the diabetic patients living across the world by the year 2030, the share of developing countries would be 77.6% (3). In addition, a national study examining the risk factors for non-communicable diseases indicated the prevalence of diabetes to be 7.7% within the age range of 25 - 64 years (4). The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that there will be more than six million diabetic patients in Iran by 2030 (5).

Diabetes control reduces the associated mortality and prevents the long-term complications of the disease (2). Nutrition plays a pivotal role in disease control and is an inherent element of the nutritional treatment of diabetes for reducing the associated mortality, morbidity, and disease complications. Receiving updated nutritional information, especially through virtual education, is essential for diabetic patients (6). Educational interventions via phone, SMS, and the internet are the new approaches to raising the awareness of diabetic patients in this regard (7, 8).

The internet is a worldwide communication system through which people communicate and exchange information anytime and anywhere (9, 10). Given the wide availability of mobile phones and their widespread use, these devices have proven efficient in health education as well (11, 12). In a study in this regard, Wangberg et al. (13) reported that SMS-based educational interventions are effective in increasing the knowledge and awareness of diabetic patients. SMS seems to be an effective tool in raising the awareness of diabetic patients (14).

The health belief model (HBM) provides an appropriate framework for educational interventions in different fields, including diabetes control. To date, this model has been used as a framework for designing and implementing educational interventions in various areas of health care (15, 16). However, few studies have investigated the effects of using virtual education on diabetic patients in Iran, and it remains unclear which e-learning method is more effective in the training of diabetic patients.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to evaluate the effect of nutrition education on the awareness of patients with type II diabetes using three electronic teaching methods based on the HBM.

3. Methods

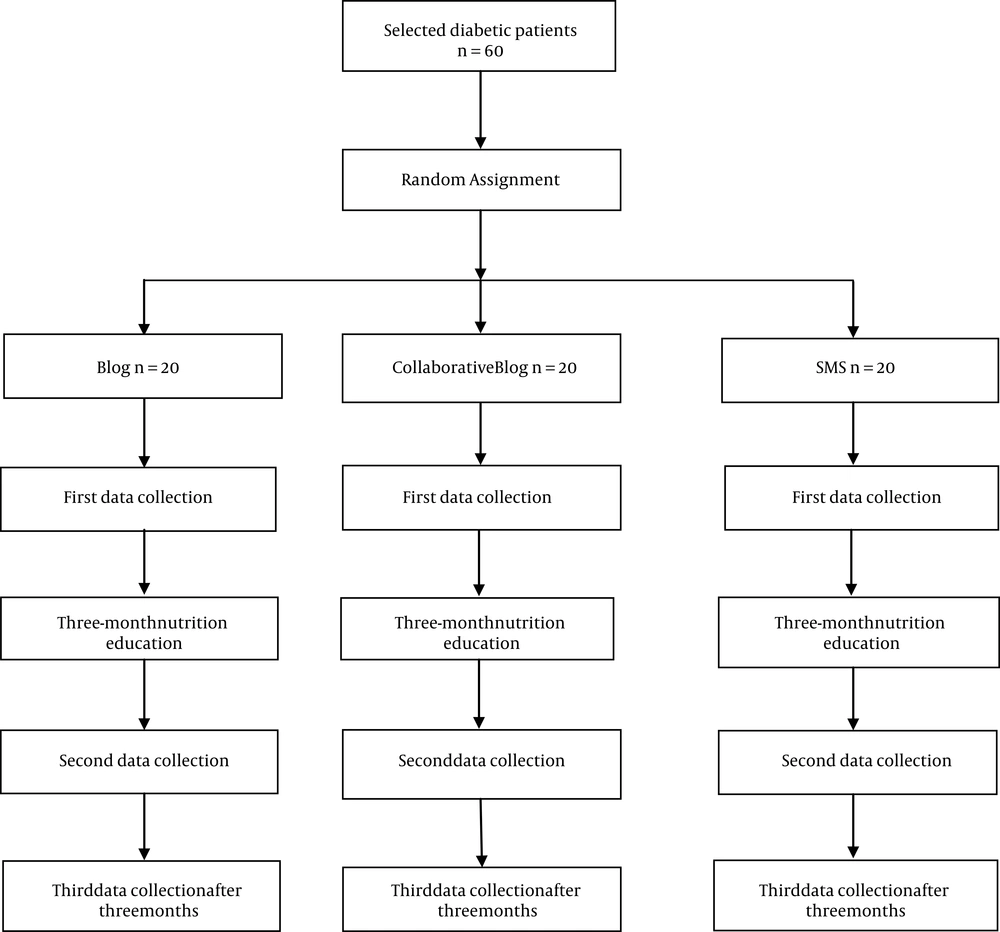

This quasi-experimental study was conducted on the patients with type II diabetes referring to a diabetes clinic in Kermanshah, Iran. The inclusion criteria were computer literacy, internet and SMS access, and computer skills. In total, 60 patients were selected via convenience sampling and randomly divided into three groups of 20, including blog, collaborative blog, and SMS. Sample size was determined at 95% confidence level and β = 0.80 based on previous studies, and 20 patients were assigned to each group. Educational needs assessment was performed at the diabetes clinic of Taleghani Medical Center via interviews with the staff and some of the patients.

Data were collected using a questionnaire that was validated by a panel of experts, including 12 faculty members of health education, nutrition, and educational psychology. In addition, the reliability of the questionnaire was measured in 21 patients as a pretest-posttest at a two-week interval, and reliability was confirmed at the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.80. The questionnaire consisted of three main sections, including demographic characteristics (15 items), nutrition knowledge (18 items; total score: 0 - 18), and items designed based on the HBM constructs (28 items). The items in the questionnaire were scored based on a Likert scale (strongly agree-strongly disagree).

The HBM has various domains, including perceived susceptibility (five items), perceived severity (five items), perceived barriers (six items), perceived benefits (six items), self-efficacy (six items), and cue to action (13 items). Notably, the weight and height of the patients were measured, and body mass index (BMI) was also measured after completing the questionnaires. For the intervention, all the patients individually used the Persian version of the national program of diabetes prevention program (17) and the Iranian regime dietetic association handbook for three months (18); these are the main references employed for educating diabetic patients. The contents of the books were used by three education methods in the present study, including blog, collaborative blog, and SMS. Immediately after the three-month intervention, the patients completed the questionnaire, and BMI was measured again. Three months after the intervention (six months after baseline), data collection was repeated without training (Figure 1), and the participants were asked to complete this stage via phone.

3.1. Statistical Analysis

Data were collected before the intervention, immediately after the intervention, and three months later. Data analysis was performed in SPSS version 22 using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, analysis of variance (ANOVA), Tukey’s post-hoc test, and the Kruskal-Wallis tests to compare the variables between the three study groups.

4. Results

In total, 60 diabetic patients were assessed in three groups of blog, collaborative blog, and SMS. No significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of age and a history of diabetes (Table 1).

| Demographic Characteristics | Blog | Group/collaborative Blog | SMS | Total | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 50.9 ± 8.2 | 52.6 ± 8.9 | 51.0 ± 9.0 | 51.3 ± 8.5 | 0.89 |

| History of Diabetes, mo | 82.0 ± 57.9 | 102.4 ± 62.3 | 87.4 ± 61.4 | 90.6 ± 60.1 | 0.55 |

At baseline, no significant differences were denoted between the study groups in terms of gender, marital status, and education level (Table 2).

| Demographic Characteristics | Blog | Group/Collaborative Blog | SMS | Total | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 41% | ||||

| Male | 60 (12) | 65 (13) | 45 (9) | 56.7 (34) | |

| Female | 40 (8) | 35 (7) | 55 (11) | 43.3 (26) | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 10 (2) | - | - | 3.3 (2) | - |

| Married | 90 (18) | 100 (20) | 100 (20) | 96.7 (58) | |

| Education level | 1.00 | ||||

| Diploma (or below) | 55 (11) | 40 (8) | 55 (11) | 50 (30) | |

| Academic | 45 (9) | 60 (12) | 45 (9) | 50 (30) |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

At baseline, awareness and BMI had no significant differences between the study groups. The obtained results also indicated that the mean score of awareness significantly decreased before, immediately after, and three months after the intervention in the blog group (P = 0.002) and collaborative blog group (P = 0.001), while no significant change was denoted in the SMS group in this regard (P = 0.308). Furthermore, no significant difference was observed in the effect of the educational intervention on awareness before, immediately after, and three months after the intervention in the blog group (P = 0.85), collaborative blog group (P = 0.670), and SMS group (P = 0.909), thereby indicating no significant change in this regard. No significant differences were denoted in the BMI and effectiveness of the intervention before, immediately after, and three months after the intervention (Table 3).

| Variable | Before Intervention | Immediately After Intervention | Three Months After Intervention | P-Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness | ||||

| Blog | 12.8 ± 2.2 | 15.2 ± 1.7 | 15 ± 1.7 | 0.002 |

| Collaborative blog | 13.2 ± 1.6 | 14.8 ± 1.5 | 14.9 ± 1.6 | 0.001 |

| SMS | 14.2 ± 2.0 | 14.8 ± 2.0 | 15.1 ± 1.0 | 0.308 |

| P-value** | 0.085 | 0.670 | 0.909 | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ||||

| Blog | 29.4 ± 4.4 | 29.3 ± 4.6 | 29.5 ± 4.0 | 0.103 |

| Collaborative blog | 27.1 ± 5.1 | 26.0 ± 5.1 | 27.1 ± 5.0 | 0.307 |

| SMS | 28.8 ± 5.2 | 29.04 ± 6.1 | 29.3 ± 6.1 | 0.449 |

| P-value** | 0.329 | 0.328 | 0.251 | - |

a*, P-value within groups; **, P-value between groups.

In the present study, no significant differences were observed in the HBM domains between the groups at baseline. However, significant differences were denoted in the tests before, immediately after, and three months after the educational intervention in the blog group in the domains of perceived susceptibility (P = 0.03), perceived barriers (P = 0.03), cue to action (P = 0.01), and self-efficacy (P ≤ 0.01). In the collaborative blog group, the significance was only highlighted in the domains of perceived severity (P < 0.01) and cue to action (P = 0.01), as well as the domain of cue to action in the SMS group (P ≤ 0.01). The effectiveness of the intervention was not considered significant in the study three groups after the intervention, with the exception of the self-efficacy domain (Table 4).

| Variable | Before Intervention | Immediately After Intervention | Three Months After Intervention | P-Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived susceptibility | ||||

| Blog | 22.20 ± 2.3 | 23.6 ± 1.7 | 22.9 ± 2.6 | 0.032 |

| Collaborative blog | 22.60 ± 2.3 | 23.5 ± 1.6 | 23.3 ± 1.6 | 0.223 |

| SMS | 23.6 ± 1.5 | 24.0 ± 1.6 | 24.0 ± 1.8 | 0.316 |

| P-value** | 0.112 | 0.557 | 0.255 | - |

| Perceived severity | ||||

| Blog | 23.2 ± 2.4 | 24.0 ± 1.7 | 22.7 ± 3.3 | 0.121 |

| Collaborative blog | 24.15 ± 1.1 | 23.15 ± 3.6 | 22.3 ± 1.9 | 0.002 |

| SMS | 24.1 ± 2.1 | 24.0 ± 1.9 | 24.1 ± 1.8 | 0.978 |

| P-value** | 0.205 | 0.492 | 0.144 | - |

| Perceived barriers | ||||

| Blog | 20.7 ± 5.4 | 23.6 ± 4.4 | 20.9 ± 4.9 | 0.026 |

| Collaborative blog | 20.0 ± 4.4 | 21.7 ± 5.1 | 20.3 ± 4.7 | 0.907 |

| SMS | 21.2 ± 5.7 | 23.3 ± 4.1 | 21.9 ± 5.9 | 0.363 |

| P-value** | 0.955 | 0.352 | 0.352 | |

| Perceived benefits | - | |||

| Blog | 26.0 ± 4.4 | 28.2 ± 1.9 | 27.0 ± 2.9 | 0.255 |

| Collaborative blog | 27.2 ± 2.2 | 27.3 ± 2.4 | 26.7 ± 2.6 | 0.873 |

| SMS | 21.15 ± 5.7 | 23.3 ± 4.1 | 21.9 ± 5.9 | 0.363 |

| P-value** | 0.092 | 0.070 | 0.178 | - |

| Cue to action | ||||

| Blog | 21.10 ± 13.9 | 27.7 ± 16.1 | 32.2 ± 16.5 | 0.011 |

| Collaborative blog | 29.30 ± 15.7 | 34.2 ± 13.4 | 40.7 ± 20.7 | 0.029 |

| SMS | 28.3 ± 15.2 | 31.2 ± 14.4 | 40.0 ± 9.3 | 0.002 |

| P-value** | 0.177 | 0.388 | 0.176 | - |

| Self-efficacy | ||||

| Blog | 24.85 ± 4.2 | 27.6 ± 2.8 | 26.0 ± 2.6 | 0.006 |

| Collaborative blog | 26.5 ± 3.1 | 25.8 ± 2.9 | 25.1 ± 3.1 | 0.055 |

| SMS | 27.0 ± 2.5 | 28.1 ± 4.2 | 27.1 ± 3.30 | 0.607 |

| P-value** | 0.133 | 0.021 | 0.121 | - |

a*, P-value within groups; **, P-value between groups.

5. Discussion

The results of the present study indicated that the mean score of awareness significantly increased in the blog and collaborative blog groups before, immediately after, and three months after the educational intervention. This is consistent with the study conducted by Noohi et al. (19). In the current research, no significant change was observed in the awareness score of the patients in the SMS group, which is inconsistent with the results obtained by Goodarzi et al. (20). In the mentioned study, the awareness of diabetic patients was reported to increase through an educational program based on sending SMS via mobile phones (20, 21).

In the present study, the patients in the blog and collaborative blog groups experienced a more effective intervention compared to those in the SMS group. Furthermore, significant differences were observed within the collaborative blog group in terms of perceived susceptibility, perceived barriers, self-efficacy, and cue to action. In the SMS group, only the domain of cue to action was considered significant. These findings are in line with the previous studies investigating dietary interventions (22).

Our findings demonstrated no significant changes in the study groups regarding various HBM domains, especially the perceived benefits domain. Correspondingly, high mean scores were obtained in the perceived benefits domain by the diabetic patients in the blog, collaborative blog, and SMS groups. In addition, the scores of the patients in the perceived severity domain were considered significant in the collaborative blog group, which could be attributed to the prolonged disease history of these patients.

The present study indicated that all the HBM domains (perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived barriers, perceived benefits, and cue to action) improved in the patients with type II diabetes, with the exception of the self-efficacy domain; this is inconsistent with the results obtained by Papzan et al. (23).

5.1. Conclusions

According to the results, using blogs, group/collaborative blogs, and SMS could effectively enhance the awareness of diabetic patients regarding their disease. Moreover, virtual education proved effective in improving various structures of the HMB, except perceived sensitivity. Therefore, it is recommended that a framework be designed and implemented based on the structures of the HBM for educating diabetic patients properly.