1. Background

Over the past decades, the importance of spirituality and spiritual well-being in humans has attracted the attention of psychologists and mental health specialists. The development of psychology on the one hand and the dynamic and complex nature of the modern communities on the other hand have caused the spiritual needs of humans to become more important than their material needs (1). The importance of spirituality and its role in psychological well- being have caused several health organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) to review their definitions of human and human nature. For instance, WHO considered the existential dimensions of humans to be physical, psychological, social, and spiritual, stating that the fourth dimension, i.e., spiritual dimension, is vital for human growth and development (2).

The biopsychosocial-spiritual model is employed to treat psychological disorders. It must be noted that all four dimensions are taken into account in the treatment of psychological disorders since integration is essential for a healthy personality (3). Since the birth of modern psychology, personality, integration, and its related concepts have been mentioned in numerous definitions of personality. Therefore, spiritual needs and attitudes are considered to be the most inevitable and transcendental needs of humans. In accordance with several studies, when individuals and communities deal with ethical and identical crisis due to the increasing pressure of changes and developments, spirituality can have a considerable effect on individuals’ meaningfulness and continuity (4, 5). The advocates of the role of spirituality in the improvement of psychological well- being and interpersonal adjustment took measures to develop the relationship between health and spirituality to account for spiritual well-being structure (6).

Spiritual well-being consists of one psycho-social element and one religious element. Religious well-being, which is a religious element, indicates the relationship with a higher power, i.e., God. Existential well-being is a psycho-social element and indicates individuals’ feelings regarding who they are, what they are doing and why, and where they belong to. Both religious well-being and existential well-being include self- transcendence and self- movement. The religious well-being dimension guides us towards God, while the existential well-being dimension leads us beyond ourselves and towards others and our environment (7, 8). Feizi et al. (9) defined spiritual well-being as a combination of religious well-being, the individual’s relationship with God and existential well-being, and the individual’s relationship with the world, which includes the feelings of meaning, satisfaction, and purpose of life. Spiritual well-being is a state of health that indicates positive cognitions, behaviors, and feelings regarding the relationship with the self, others, nature, and a higher being and causes a coordinated and integrated relationship between individuals. Spiritual well- being is recognized by the properties such as stability in life, peace, proportion and coordination, and the feeling of close relationship with the self, God, society, and the environment. When the spiritual well-being is at risk, the individuals might suffer from mental disorders such as the feeling of loneliness, depression, and losing the meaning of life, which can cause problems in adjustment in life, especially eternal life (10). The studies have manifested that spiritual experiences are affective in improving psychological well- being and physical health. Furthermore, the score of spiritual well-being scale had a significant relationship with emotional well-being, life satisfaction, self-esteem, and depression (11, 12).

BJW is crucial in individuals’ adjustment to the adverse and unjust conditions, their manner of dealing with the problems, and their mental health. Humans have a fundamental tendency to believe in a just world (13). BJW enables individuals to consider the world as a stable, orderly, and secure place. Humans’ perceptions of justice eventually lead to general beliefs as whether the world conditions are just or unjust. Individuals would believe that all people will get what they deserve (14). According to this assumption, good people will have a good ending and bad people will have a bad ending. BJW is the belief in a fair and justice-oriented world that rewards endeavors and diligence. However, BUW is the belief in a mortal world where the principles of justice are not applied, and people’s endeavors, diligence, and planning do not lead to well-deserved results. Accordingly, it is the belief in a world that causes diseases, discrimination, hostility, animosity, conflict, and aggression among humans with no legitimate reason (15). Numerous studies have demonstrated that a great number of subjective well-being or psychological well- being indicators; such as positive affects, optimism, coping with stress, good sleep, and the lower levels of depression, loneliness, and sadness are all related to BJW (13, 14).

Nartova-Bochaver et al. (16) indicated a significant positive relationship between BJW and spiritual well-being. Consequently, BJW lays the ground for spiritual well-being. According to different studies, the mediating factors of spiritual well-being are positive and negative affects. In general, ordinary human beings experience different moods, including positive or negative affects. Positive affect includes positive feelings and emotions such as pleasure, pride, satisfaction, and negative affect includes negative feelings and emotions such as anxiety, sadness, rage, guilt, and shame (17).

Positive affect indicates a pleasant challenge with the surrounding environment and is identified by properties such as feelings of enthusiasm, high energy, and awareness. However, the negative affect demonstrates people’s experiences of despair, dissatisfaction, and unpleasant emotions and is distinguished by properties such as guilt, fear, rage, and anxiety (18). Positive and negative effects have different relationships with psychological well- being indicators such as depression and anxiety. Negative affect has a positive relationship with anxiety and depression and positive affect has a negative relationship. Furthermore, higher levels of positive affect have a positive relationship with job satisfaction, marital life, and physical health. Positive affect results in effective problem solving, better decision-making capability, and higher creativity (19, 20). According to the study, positive affect and emotions might enhance an individual’s resistance to negative events and prevent psychological and even physical disorders. People with positive affect are extrovert and respect pleasure, reward, and happiness. However, people with negative affect have a tendency towards aggression, fear, and anxiety. Positive affect is a positive predictor of well-being and life satisfaction, and negative affect is a negative predictor of them (21). Positive affect can expand individuals’ cognitive environment and influence their creative thinking. This signifies that positive emotions cause more flexibility and result in a broad spectrum of interests which entail dynamic benefits including developing skills and increasing physical, psychological, and social resources (22).

2. Objectives

Based on the above considerations, the main objective of the current study was to predict a model of spiritual well-being based on belief in a just world through the mediation of the positive and negative effects in university students of Tehran.

3. Methods

This is a descriptive correlational study. The statistical population consisted of students studying at different universities in Tehran during 2020 - 2021. The research sample consisted of 301 students (199 female and 102 male). The participants completed the questionnaires online, due to the Covid-19 pandemic and failure to have direct access to students. First, the questionnaires were sent to the students who were available, and they were asked to complete the questionnaires and send them to other students if possible. Taking into account that the minimum sample size for structural modeling, according to most researchers, should be at least 200 (23), a total of 301 questionnaires (199 female and 102 male) were collected from the participants. The inclusion criteria were being a university student, having no mental disorders, and showing consent to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria included failure to answer all the questions.

3.1. Research Instruments

The Spiritual Well-being Questionnaire: This questionnaire, designed by Paloutzian and Ellison (1982), is a 20-item questionnaire, and consists of two subscales; spiritual well-being and existential well-being. The former subscale measures the relationship with a superior power, while the latter, a social-psychological element, evaluates individuals feeling about who they are, what they are doing and why, and where they belong to. Items are scored on a six-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Positively worded items were rated on a 1-6 scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree, respectively. Negatively worded items were reverse-scored (Items 1, 2, 5, 6, 9, 12, 13, 16, 18). All items were summed to obtain the overall score of the spiritual well-being questionnaire (24). Jafari et al. (25) calculated the reliability of the questionnaire using Cronbach's alpha, which was 0.81. In this study, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.92 for the questionnaire.

The Belief in a Just World Questionnaire: This questionnaire was designed by Sutton and Douglas (2005) and was translated into Persian by Golparvar and Arizi (2007). It contains 27 items and 4 subscales of BJW for self, BJW for others, general BJW, and BUW. The items were scored on the five-point Likert scale. Rahpardaz and Shirazi (26) reported the reliability of the Persian version of the questionnaire at 0.83. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.87 in the present study.

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule was designed by Watson (1988) and is a self-report scale comprising of 10 items on positive affect, 10 items on negative affect, and 2 subscales of positive and negative effects. This scale measures the variables on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to five (always). Díaz-García et al. (27) reported a Cronbach's alpha of 0.91 for the scale. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.81 for this scale.

3.2. Statistical Analyses

The research measurement model was evaluated using the confirmatory factor analysis, and the Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation method in Amos 24.0.

4. Results

The participants were 199 female students (66.10%) and 102 male students (33.90%). Among them, 64 participants (21.30%) were associate students, 124 (41.20%) were bachelor students, 80 (26.60%) were master students, and 33 (10.90%) were Ph.D. students.

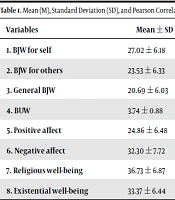

Table 1 shows the mean, standard deviation, correlation coefficient between the components of BJW (BJW for self, BJW for others, general BJW, and BUW) and BUW, positive and negative effects, and spiritual well-being (religious well-being and existential well-being). There was a significant positive correlation between the components of BJW and positive affect, but a significant negative correlation between BUW and negative affect with the components of spiritual well-being at the significance level of 0.01 (Table 1).

| Variables | Mean ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. BJW for self | 27.02 ± 6.18 | 1 | |||||||

| 2. BJW for others | 23.53 ± 6.33 | 0.72** | 1 | ||||||

| 3. General BJW | 20.69 ± 6.03 | 0.66** | 0.81** | 1 | |||||

| 4. BUW | 3.74 ± 0.88 | 0.25** | -0.28** | -0.26** | 1 | ||||

| 5. Positive affect | 24.86 ± 6.48 | 0.40** | -0.35** | -0.34** | 0.02 | 1 | |||

| 6. Negative affect | 32.30 ± 7.72 | 0.24** | 0.13* | 0.11 | 0.28** | -0.16** | 1 | ||

| 7. Religious well-being | 36.73 ± 6.87 | 0.48** | 0.33** | 0.39** | -0.32** | -0.48** | 0.40** | 1 | |

| 8. Existential well-being | 33.37 ± 6.44 | 0.47** | 0.30** | 0.37** | -0.36** | -0.44** | 0.44** | 0.76** | 1 |

Mean, Standard Deviation, and Pearson Correlation Coefficient of the Variablesa

To examine the normal distribution assumption of the single-variable data, the skewness and kurtosis of each variable were calculated, and to examine the collinearity assumption, the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance coefficient were calculated (Table 2). As shown in Table 2, the skewness and kurtosis of all variables range between +2 and -2. Consequently, the data distribution of the research variables has no clear deviation from single-variable normality. Furthermore, the tolerance coefficients of all predictor variables are higher than 0.1 and their VIFs are lower than 10. These findings indicate the collinearity of the variables.

| Variables | Normality | Collinearity | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skewness | Kurtosis | Tolerance Coefficient | Variance Inflation Factor | ||

| BJW for self | -0.21 | -0.33 | 0.34 | 2.360 | 0.180 |

| BJW for others | -0.13 | -0.28 | 0.23 | 3.54 | 0.211 |

| General BJW | 0.08 | -0.16 | 0.33 | 3.03 | 0.142 |

| BUW | -0.32 | -0.05 | 0.84 | 1.19 | 0.109 |

| Positive affect | -0.03 | -0.12 | 0.81 | 1.24 | 0.115 |

| Negative affect | -0.16 | -0.38 | 0.87 | 1.15 | 0.312 |

| Religious well-being | -0.14 | -0.71 | - | - | 0.338 |

| Existential well-being | -0.16 | 0.47 | - | - | 0.249 |

Evaluation of the Normality and Collinearity Assumptions

Table 3 shows the fitting indicators for the measurement model and the structural model. According to Table 3, all fitting indicators associated with the confirmatory factor analysis support the acceptable fitting of the measurement model with the collected data (χ2/df = 2.78; CFI = 0.997; GFI = 0.991; AGFI = 0.932; RMSEA = 0.078).

| Fitting Indicators | Structural Model | Measurement Model | Cut-off Point |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | 11.13 | 36.12 | - |

| df | 4 | 14 | - |

| (χ2/df) | 2.78 | 2.58 | > 03.00 |

| GFI | 0.991 | 0.971 | > 0.90 |

| AGFI | 0.932 | 0.919 | > 0.85 |

| CFI | 0.997 | 0.983 | > 0.90 |

| RMSEA | 0.078 | 0.072 | > 0.08 |

Fitting Indicators of the Measurement and Structural Models

Table 4 reveals path coefficients between the variables of the structural model of the research. As this table shows, the path coefficient between the positive affect and spiritual well-being is positive and significant (β = 0.312, P < 0.01). Furthermore, the path coefficient between the negative affect and spiritual well-being is significant and negative (β = -0.328, P < 0.01). Table 4 shows that the total path coefficient between BJW and spiritual well-being is significant and positive (β = 0.388, P < 0.01). Furthermore, the path coefficient between BUW and spiritual well-being is significant and negative (β = -0.239, P < 0.01). The indirect path coefficient between BJW and spiritual well-being is positive and significant (β = 0.198, P < 0.01). Accordingly, the positive and negative affect mediate the relationship between BJW and spiritual well-being positively and significantly at the 0.01 level.

The Baron and Kenny's formula revealed that the path coefficient between BJW and spiritual well-being with negative affect was positive and significant (β = 0.190, P < 0.01), and in addition, the indirect path coefficient between the two aforesaid variables with positive affect was insignificant (β = 0.032, P > 0.05). Accordingly, it was concluded that the negative affect made the relationship between BJW and spiritual well-being significantly positive.

| Paths | Path Type | B | SE | β | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive affect to spiritual well-being | Direct | 0.254 | 0.046 | 0.312 | < 0.001 |

| Negative affect to spiritual well-being | Direct | -0.370 | 0.061 | -0.382 | < 0.001 |

| BUW to positive affect | Direct | -0.591 | 0.148 | -0.249 | < 0.001 |

| BUW to negative affect | Direct | -0.236 | 0.119 | -0.119 | 0.046 |

| BJW to positive affect | Direct | 0.148 | 0.116 | 0.093 | 0.173 |

| BJW to negative affect | Direct | -0.592 | 0.085 | -0.444 | < 0.001 |

| BUW to spiritual well-being | Direct | -0.397 | 0.102 | -0.206 | < 0.001 |

| BJW to spiritual well-being | Direct | 0.254 | 0.082 | 0.190 | < 0.001 |

| BUW to spiritual well-being | Indirect | -0.062 | 0.070 | -0.032 | 0.406 |

| BJW to spiritual well-being | Indirect | 0.256 | 0.053 | 0.198 | < 0.001 |

| BUW to spiritual well-being | Total (direct and indirect) | -0.460 | 0.123 | -0.239 | < 0.001 |

| BJW to spiritual well-being | Total (direct and indirect) | 0.502 | 0.087 | 0.388 | < 0.001 |

Path Coefficients Between the Variables of the Structural Model of the Research

5. Discussion

The present study aimed to predict a model of spiritual well-being based on belief in a just world through the mediation of the positive and negative effects in students studying at different universities of Tehran during 2020-2021. The structural model of the present research assumed that the belief in just and unjust worlds predicts the positive and negative effects of spiritual well-being both directly and through the mediating factors. The results indicated a positive and significant path coefficient between the positive affect and spiritual well-being and a negative and significant path coefficient between the negative affect and spiritual well-being, meaning that positive affect significantly increases spiritual well-being whereas negative affect decreases it.

As already stated, the positive and negative effects have different relationships with the health indicators. The positive affect has a positive while the negative affect has a negative relationship with the various health dimensions including spiritual well-being. Therefore, experiencing positive affect such as happiness, pleasure, pride, satisfaction, and optimism increases spiritual well-being, i.e., better relationship with self, society, natural environment, and God. The individuals' relationship with self, others, nature, and a higher power helps them to experience a state of health, including positive cognitions, behaviors, and feelings (19). An increase in spiritual well-being can improve the quality of emotional well-being, life satisfaction, self-esteem, and can reduce depression and anxiety, and lead to a healthy and hopeful life. Accordingly, the higher the individuals' positive affect, the higher their creativity, openness, and empiricism and the lower their anxiety. Consequently, the individuals can have better relationship with self, natural environment, others, and God. However, negative affect increases individuals’ inclination to aggression, fear, and anxiety (21). This causes unpleasant feelings towards self, the perception of the negative indicators, and building fewer social relationships, since these individuals perceive every event or occurrence as a threat not an opportunity.

Furthermore, the results revealed a positive and significant path coefficient between BJW and spiritual well-being and a negative and significant path coefficient between BUW and spiritual well-being, meaning that BJW significantly increases spiritual well-being and BUW decreases spiritual well-being. The main positive outcomes obtained for BJW regarding emotions and affect were life satisfaction and the reduction of depression, anxiety, and poor social performance (13). These beliefs can affect individuals’ psychological health due to their cognitive function. The important functions of these beliefs include preparing individuals to plan for the future, generating diligence and motivation for the planned goals, helping to adjust to unpleasant and unfair situations, assisting to deal better with problems, and maintaining psychological health (16). Yet, BUW reduces spiritual well-being, which is one of the health dimensions. BUW means belief in a mortal world, which is not subject to the principles of justice, where people’s endeavors, diligence, and planning do not lead to well-deserved results. Finally, it is the belief in a world that causes diseases, discrimination, hostility, animosity, conflict, and aggression among humans for no legitimate reason. Certainly, when humans believe in such a world, they cannot hope for the future, make efforts, carry out their works with purpose, make long-term plans, and establish a proper relationship with self, God, natural environment, and society. Thus, they will suffer from lower psychical and psychological health and lower spiritual well-being (26). It can be concluded that expanding justice in society, strengthening BJW, and establishing a just world can contribute to humans’ spiritual well- being. People who believe that the world will give them what they deserve will make more plans, try more, and demonstrate more diligence as a cognitive motive, which increase their spiritual well-being.

Other findings indicated that the indirect path coefficient between BJW and spiritual well-being was significant and positive. Accordingly, the positive and negative affect act as a positive mediator between BJW and spiritual well-being since the positive and negative affect have different effects. This effectively signifies that people with positive affect are extroverts who seek pleasure, reward, happiness, and so forth. However, those with negative affect are more inclined towards aggression, fear, and anxiety. Positive affect is the positive predictor while negative affect is the negative predictor of well-being and life satisfaction.

According to the results, there was a positive and significant path coefficient between BJW and spiritual well- being with negative affect, and an insignificant indirect path coefficient between the two aforesaid variables with positive affect. Accordingly, it was concluded that the negative affect had a positive and significant effect on the relationships between BJW and spiritual well-being (16). Thus, when facing accidents or unfair and unjust events, the individuals will have strong BJW and experience negative affect and even though at first they might get angry, they will become relaxed at the end as they believe that the world will do them justice. Individuals experience such cognitive situations in different life events. It sets the grounds for interpersonal trust, forgiveness, and efficiency and results in spiritual and psychological well-being.

The study suffers from some limitations including the Covid-19 pandemic, the lack of direct access to students, and online collection of the questionnaires. Therefore, the researcher cannot guarantee whether all participants were students or not. In addition, the researcher cannot ensure that all the participants were studying at universities of Tehran. The results of the present study must be generalized to other groups with caution.

5.1. Conclusions

According to the results, it can be concluded that BJW and positive affect and strengthening them can enhance the level of spiritual well-being and reduce the students’ negative affect, anxiety, and depression levels. Spiritual well-being plays a significant role in increasing physical, psychological, emotional, and social well- being, improving individual and social functions, and strengthening life expectancy. Therefore, addressing this issue and educating it to different groups, including students can improve individuals and society well- being, both through BJW and mediating role of positive emotions.