1. Background

Inactivity or lack of regular physical activity is the fourth leading cause of death worldwide. Sedentary rates are increasing in many developed countries, which can negatively affect people’s health worldwide (1). Obesity is increasing in developing countries due to lifestyle changes caused by economic development, positive energy balance, and changes in socio-cultural conditions (2). Parents are responsible for eating habits, attitudes, and behaviors in early adolescence, and these attitudes can play an essential role in healthy eating habits and behaviors (3). Adolescence is establishing correct eating habits to prevent health and nutritional problems (4). Some new food tendencies in adolescence are caused by psychological and physiological changes during puberty (5).

Studies have shown that children who gain weight faster than others in the first years of life are more likely to be obese in adulthood (6). The world health organization ranks obesity and overweight among the six leading causes of death worldwide (7). Improper diet and inactivity are the essential environmental factors of obesity and overweight as the most critical of non-communicable diseases (8). Eating habits and behaviors in children can be different as they tend to skip meals and consume junk food and snacks (6). Michael Jacobson coined the phrase "junk food" in 1972 to describe unhealthy or innutritious foods (9). Junk food includes high-calorie foods, especially added fats and sugars, but low in micronutrients (vitamins and minerals), such as chocolate, industrial juices, chips, fried potatoes, Mexican corn, cakes, biscuits, a variety of sandwiches and ice cream, desserts, and chewing gum (10, 11). Consumption of junk food by children can lead to their dependence on these substances and the occurrence of overweight and obesity, which can also affect their school performance and extracurricular activities. Few studies have investigated this issue. Lamba and Garg found that boys and girls who were accustomed to eating junk food scored lower in jumping and 100-meter running than other groups (12).

Adolescents consist of more than one-fifth of the world’s population. Physiological and psychological factors in this period can affect adolescents' health, whose ignorance leads to adverse consequences such as weight gain and obesity (6, 13). Children and adolescents tend to eat high-fat, sugary, salty foods and fruits, vegetables, and whole grains (14). Studies in Iran have also shown the poor nutritional status of this group. Children and adolescents in Iran are changing their eating habits from traditional to fast foods. Surveys have shown that children consume various junk food such as puffs, industrial juices, and chocolates during the week (15). Malnutrition, on the other hand, can adversely affect physical activity. To perform proper physical activity, the body needs quality nutrients. The trend toward junk food has become one of the health issues of adolescents, which is popular among children and adolescents due to their attractive appearance, taste, cheapness, and ease of consumption (9).

2. Objectives

This study evaluated the correlation between junk food consumption and health-related physical fitness factors in Kamyaran students.

3. Methods

The study population included all 10 - 12 years old students in 2021 - 2022, of whom 1514 were students. The schools were selected using multi-stage cluster sampling, and then 350 students were randomly and voluntarily selected based on Morgan’s table. As the students were not of legal age, the research was presented separately to their parents in a face-to-face meeting, and their consent was obtained. Then, the main details of the tests and distributing questionnaires were given to the students. A wall-mounted static meter was used to measure the height of the samples. Students leaned against the wall with their feet without shoes, and the measurement from the heel to the highest point of the head was calculated on a centimeter digitalized medical scale with 1% accuracy used to measure students’ weight. For this purpose, the student went on the scale with minimal clothes and no shoes, and their weight was recorded in kilograms. A questionnaire was used to assess and measure the amount of junk food consumption. This questionnaire has 18 types of junk food mentioned in different sources: Fast foods, snacks, and non-nutritious foods. This questionnaire recorded the amount consumed per day, week, and month for each food item.

According to the total frequency of junk food consumption, the researcher can group the subjects according to the desired period. Ten sports sciences professors confirmed the content validity of the questionnaire with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78. National Health and Nutrition Survey (NHANES-I) was used to measure body mass index. Accordingly, > 95 cut-off BMI is obesity, 85 to 95 cut-off BMI is overweight, 15 to 85 cut-off BMI is normal weight, and < 15 cut-off BMI is thinness for age and sex. This classification divides body mass index into four groups: Thinness, normal weight, overweight, and obesity (4). A 46-question questionnaire was used to measure students’ nutritional knowledge, attitude, and behavior. The mean calculated validity ratio of the whole questionnaire was 87%, and the mean validity index was 85%. The scientific reliability of the questionnaire was determined by a test-retest (Pearson correlation coefficient) of 80%, and the internal correlation of Cronbach’s alpha was 82%.

The Irrational Food Beliefs Scale was designed by Osberg et al.. This scale is a self-assessment tool with 57 phrases and two subscales of irrational foods beliefs and logical beliefs (due to a mismatch with culture, two questions have been removed, and the Persian version has 55 questions) (16). Osberg et al. used Cronbach’s alpha to measure the internal consistency of the scale, which was 0.89 and 0.70 for both irrational food beliefs and logical beliefs, respectively. The Test is answered using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from opposite to entirely agreeable, and each test material is scored between 0 and 3 (0 = opposite, 1 = opposite, 2 = agreed, 3 = completely agreed). The scores of each subsume are gathered together. Obtaining a high score in the subsume of irrational foods beliefs indicates irrational foods beliefs, and a high score in the subsume of logical beliefs indicates logical foods beliefs (16). According to the results of the junk food consumption questionnaire, the student was divided into four groups very high dependency (more than 3000 times per year), high dependency (2000 - 3000 times per year), less dependency (1000 - 2000 times per year) and independent (less than 1,000 times per year). The questionnaires were distributed and filled out among students. Then, health-related fitness tests were taken based on the groups. A 540-meter test was utilized to measure the cardio-respiratory endurance of students. A modified supine pull-up test was applied to measure the endurance and strength of shoulder muscles, sit-up tests were used to measure abdominal muscle endurance, and a flexibility box was considered to measure the flexibility of the lower and posterior muscles (thighs).

3.1. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the mean and standard deviation of age, height, and weight, and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (k-s) test was used to check the normality of the data. In addition, the Spearman correlation was used to investigate the correlation between junk food consumption, physical fitness, nutritional knowledge, and irrational food beliefs. A significant level of 5% was considered for all statistical tests. SPSS software version 23 was used for statistical calculations.

4. Results

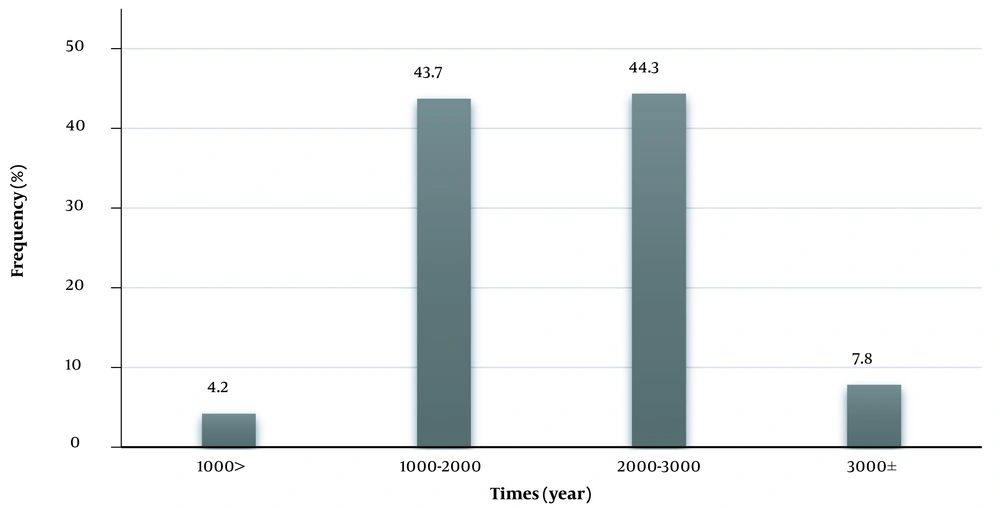

4.1. Junk Food Consumption Rate

According to the results, 52.1% of students highly depend on junk food and use junk food more than 2,000 times yearly (Figure 1).

4.2. Physical Fitness

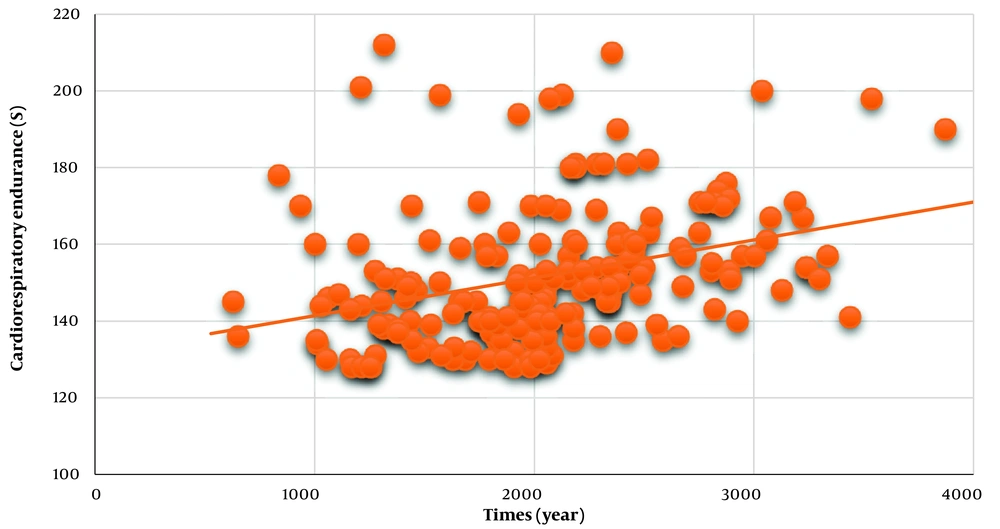

Muscle strength, muscle endurance, and flexibility decreased with an increase in junk food consumption, health-related physical fitness factors, including cardiorespiratory endurance (Figure 2), and the correlation between junk food consumption and the mentioned factors was inverse and significant (r = -0.426, r = -0.251, r =-0.245, r = -0.141, P < 0.05).

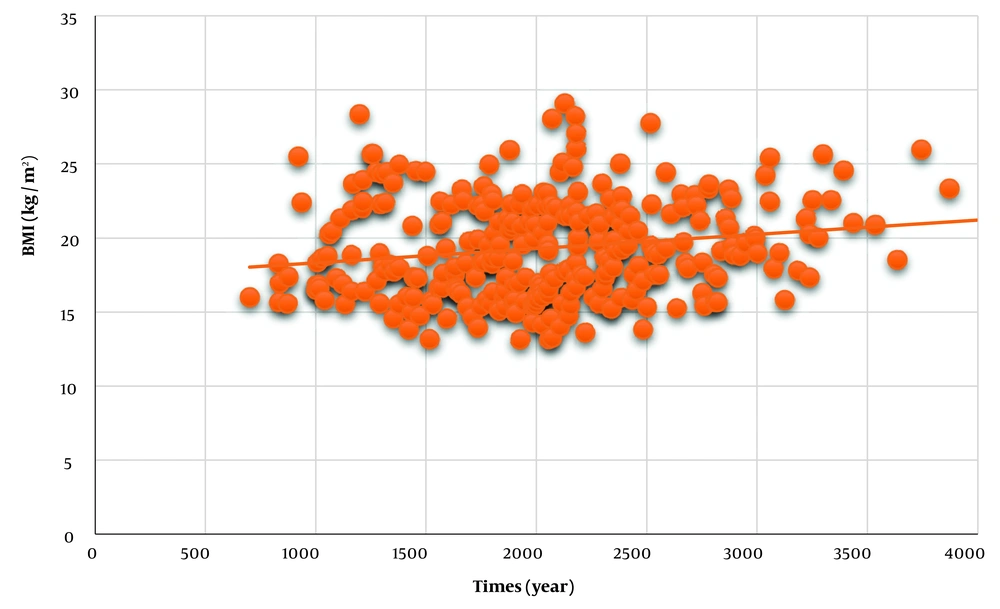

There was a significant and direct correlation between junk food consumption and body mass index in 10-12-year-old students in Kamyaran (r = 0.18, P < 0.05). In this study, 11.3% of student were lean, 57.6% had normal weight, 24.3% were overweight, and 6.8% was obese (Figure 3).

4.3. The Correlation Between Junk Food Consumption and Nutritional Knowledge, Attitude, and Behavior

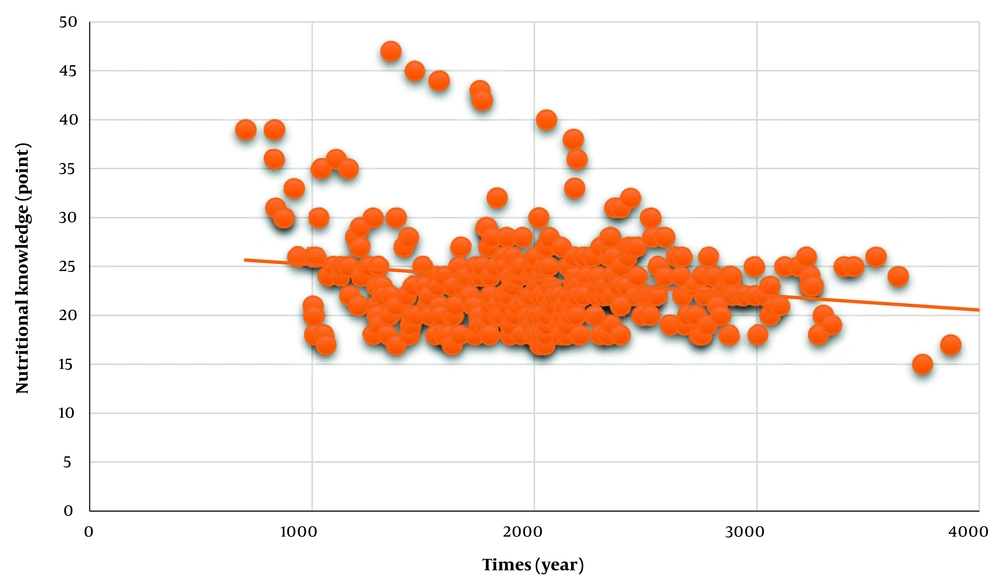

About 98.1% of students had moderate to high nutritional knowledge scores. More than 95% of them had moderate to high nutritional behavior scores. In addition, more than 90% of students had moderate to high nutritional attitudes. There was a significant and inverse correlation between junk food and nutritional knowledge in students (r = -0.25, P < 0.05) (Figure 4). There is a significant and inverse correlation between junk food and students’ nutritional behavior (r = -0.134, P < 0.05). There is no significant correlation between junk food and students’ nutritional attitude (r = 0.099, P < 0.05). Therefore, with increasing the amount of knowledge and nutritional behavior, the frequency of consumption of junk food decreased.

4.4. Correlation Between Junk Food Consumption and Irrational Food Beliefs

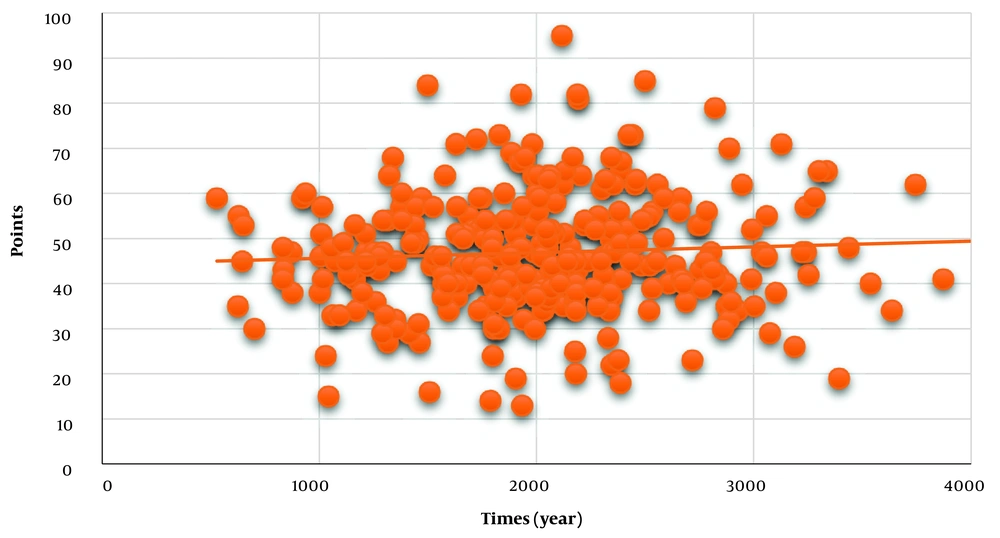

There is no significant correlation between junk food consumption and irrational food beliefs in students (r = 0.074, P < 0.05) (Figure 5). There was a significant inverse correlation between irrational food beliefs and body mass index (r = -0.18, P < 0.05). Body mass index increases with irrational food beliefs.

5. Discussion

The consumption of junk food is almost high, and some studies also obtained results consistent with this research (10, 15, 17, 18). The healthy heart survey found that the common dietary patterns obtained were junk food (19). In addition, the Caspian study in adolescents showed that the average frequency of consumption of biscuits, cakes, and chocolates was ten times a week, and salty and fatty snacks were 4.9 times a week (15). In a study in American schools, it was found that the consumption of junk food was in elementary (71%), middle (92%), and high school (93%) (18). For various reasons, including media advertising, changes in the lifestyles and eating habits of children and adolescents, and the attractive, inexpensive, and appearance of these foods, junk food attracted the attention of children and adolescents. Research has shown that excessive consumption of junk food in adolescence may have a broad functional effect on the brains of growing adolescents. Therefore, the motivation to consume large amounts of low-value and sweetened foods during adolescence increases (20). Iranians, like those in other developing countries, are more likely to contract non-communicable diseases, and their age at acquiring them is decreasing. In addition, the eating habits of Iranian children and adolescents have changed from traditional foods to prepared and junk food (15).

This study found that the number of physical fitness factors related to health decreased significantly with the increase in the consumption of junk food. Some studies have been consistent with the results of the present study (12, 21). Limited studies have evaluated the association between junk food and fitness. Lamba and Garg showed that people who used to consume junk food were more overweight compared to other groups. The result also indicated that boys dependent and less dependent on junk food had significantly lower jumping scores than non-dependent adolescent boys (12). In addition, Nazarali showed that increased fat consumption, which is also high in junk food, decreased some physical fitness tests' scores (sit-ups, flexibility, and agility tests) (21). However, contrary to the results of this study about junk food and physical fitness, in Ottevaere et al., the correlation between the amount of energy intake and the level of physical activity (which is related to physical fitness) was not observed (22). This difference in the results may be due to the variety of foods evaluated, the difference in physical fitness tests and physical activity, and the age difference of the difficulties related to the present study.

The overweight and obesity rate in the present study has been reported to be high (31.1%), and the correlation between junk food consumption and body mass index has been significant and direct. Many studies have been in line with the results of this study (21, 23-27). For example, the American Drug Administration found that children’s access to unhealthy foods at school is essential because of the vital link between overweight and obesity in adolescence (14). In addition, Hosseini reported a significant correlation between BMI and snack consumption (27). van der Horst et al., was found that foods and drinks (sweet and fatty) sold in and around schools can affect child obesity (28). The results of Shahidi et al. and Nazarali were in line with the present research. Researchers have confirmed consuming more junk food in overweight and obese adolescents (21, 29).

The amount of nutritional knowledge, attitude, and behavior was almost high, and junk food consumption decreased with increasing expertise and nutritional behavior. Delavarian Zadeh was consistent with the present study and showed that most subjects had moderate to high nutritional knowledge, attitude, and behavior (25). van der Horst et al. also showed a significant correlation between adolescents’ nutrition knowledge and consuming soft drinks and junk food (28). According to the findings, nutritional knowledge, attitude and behavior could play a decisive role in eating habits. However, in this study, the correlation between junk food and nutritional attitudes was not significant, possibly due to a cross-sectional study and misunderstanding of subjects’ nutritional attitudes questions. Considering the influence of nutritional attitudes on the eating habits of adolescents, it seems that complete research is necessary to investigate the causes of poor nutritional attitudes in adolescents.

Contrary to the results of the present study, some studies have shown that nutritional knowledge is low in different groups of people. This lack of nutritional knowledge has been seen even in the community of physicians and athletes. For example, Hazavehei et al. reported low nutritional knowledge in secondary schools in Isfahan (26). Some research has shown that although adolescents’ nutritional knowledge was adequate, they failed to perform eating behaviors. Children have a good understanding of the negative effects of poor diets and lack of physical activity on physical health, but children face significant barriers to turning their knowledge into action without a supportive environment (24, 30).

In this study, 81.2% of students scored low on the irrational food beliefs scale. In general, most students had fewer irrational food beliefs. In addition, the body mass index decreased with increasing irrational food beliefs. Some studies have been in line with the results of the present study (20, 31, 32). Limited studies have measured rational and irrational food beliefs. For example, contrary to the results of the present study, Kalantari reported high levels of irrational food beliefs in subjects (33). Consistent with this study, Eadhamian and Hashemie found that the obese group had the highest score on the scale of irrational food beliefs. Cognitions influence health-related behaviors, and irrational food beliefs have been reported as persistent and influential factors in obesity. For example, there was a significant difference between obese and overweight people and between obese and normal-weight people in irrational food beliefs (34). Osberg and Eggert showed that people with irrational food beliefs could alleviate negative feelings in a given situation when they are under stress (31). Wamsteker et al. also found that personal beliefs contributed to and predicted weight change and obesity (32).

5.1. Limitations

A limitation of this study is its cross-sectional nature. In addition, the mental and motivational conditions of the subjects could not be controlled during the physical fitness tests.

5.2. Conclusions

Based on the results, there was a significant inverse correlation between junk food consumption and health-related physical fitness factors, but there was a direct and significant correlation between junk food consumption and body mass index. Adolescents’ physical fitness and diet were vital factors, which could guarantee society’s future health. In addition, the school was essential in implementing various nutritional and sports policies to improve students’ physical fitness and nutritional status during childhood and adolescence. Therefore, parents and policymakers of nutrition and fitness should pay more attention to health and physical activity in society and school students and plan better in the mentioned fields.