1. Background

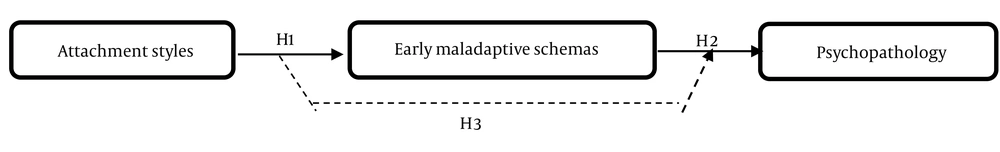

Cosmetic surgery is a specialty for appearance improvement that restores, maintains, or improves a person’s physical appearance through surgical and medical techniques (1). Cosmetic surgery can improve people’s quality of life, but the problem is that cosmetic surgery has become one of people’s concerns. Therefore, thousands undergo cosmetic surgery yearly and change their physical appearance (2). The role of medical advances in increasing demand is vital because of providing new methods to improve appearance with cosmetic surgery (3). Many studies have shown that the prevalence of psychological disorders, including body deformity, among cosmetic surgery applicants is higher than among normal people (4, 5). The importance of motivation and the reason for cosmetic surgery cannot be overstated. However, it is important to know the difference between common wishes to improve appearance and neurosis. Extreme dissatisfaction with appearance may cover pathological psychological states, and neglecting it can have serious medical consequences (6). The studies comparing psychological disorders in cosmetic surgery applicants with non-applicants in Iran have also aligned with studies in other countries, indicating significant psychological vulnerability in psychological disorders in cosmetic surgery applicants. Some studies have reported a significant difference between the two groups of applicants and non-applicants of cosmetic surgery in all dimensions except for the two dimensions of paranoid thoughts and psychosis (7). Thus, a psychiatric evaluation of those who want beauty has been of interest since the past, and it is necessary to identify predictors of psychological vulnerability in society. Attachment is often considered the insecure attachment model related to many psychological disorders. Attachment theory describes how the relationship between the baby and the caregiver is formed. During development, people record psychological evidence for their success through sufficient proximity by attachment figures as internal models (8). Attachment styles are the internal models resulting from the deep emotional relation between child and mother, which determine the form of behavioral responses of individuals to the separation of attachment images and reconnection with these images. These styles are divided into three categories: Secure, avoidant, and ambivalent (9-11). Avoidant and ambivalent attachment has a positive relationship with various indicators of psychological distress, including depression and anxiety, negative mood, and psychological distress (12). In addition to a linear and direct relationship between attachment and psychopathology, researchers have tried to identify factors that indirectly affected this relationship. Some studies have indicated that early maladaptive schemas have an intermediary role. Young et al. have identified 18 early maladaptive schemas in five domains according to the five developmental psychological needs of the child. (1) The disconnection and rejection: In this area, the individual’s need for safety, health, protection, stability, empathy, and acceptance will not be satisfied. (2) Impaired autonomy and performance: A firm belief based on failure to do duty independently and lack of success, which leads to feelings of inadequacy. (3) Impaired limits: Weakness and inability to determine internal boundaries, responsible performance, or coherent activity to achieve long-term goals. (4) Directedness: An extreme emphasis on satisfying the needs of others rather than one’s own. (5) Over-vigilance and inhibition: Extreme emphasis on inhibition or regression of individuals’ emotions, impulses, and spontaneous choices or satisfying internal and inflexible rules and expectations about moral performance and behavior (13, 14). Young (15) believes that each symptom of psychopathology with one or more schemas causes negative spontaneous thoughts and intense psychological distress. Research investigating the mediated role of emotional schemas in the relationship between attachment styles and psychological distress has shown an indirect relationship between attachment styles and psychological distress considering emotional schemas as a mediated factor (16). Based on cognitive-behavioral theories, individuals’ appearance evaluation depends on their schemas regarding appearance (17). Beck believes that our emotions and behaviors are created by cognitive schemas caused by past experiences and affecting the world’s perception (18). Most of the research has shown that females applying for cosmetic surgery have obtained higher scores in the early maladaptive schema, and there is a significant difference between applicant and non-applicant females (19). These results indicate that the applicant’s safety, protection, health, and acceptance needs have not been consistently satisfied. In many cases, these patients do not have the attention, sincerity, and companionship of others, and they lack a supportive source, which is why they did cosmetic surgery; they want a supportive relationship (20, 21). This study aims to investigate the hypotheses that consider the target society’s importance, sensitivity, and complexity and the potential capacity of Bowlby’s attachment theory (22) in describing and explaining psychopathology, especially the role of early maladaptive schemas. Psychopathology correlates positively with attachment styles, and psychological disorders positively correlate with early maladaptive schemas (Figure 1).

2. Objectives

This research aimed to investigate the model of structural relationships of the mentioned variables about the mediated role of early maladaptive schema in the relationship between attachment styles and psychopathology in cosmetic surgery applicants.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This study was descriptive and based on correlational models of females applying for cosmetic surgery in Kermanshah, Iran, 2016. About 300 females using cosmetic surgery in the specialized cosmetic surgery centers in Kermanshah (clinics and offices providing cosmetic surgery services for ear, nose, throat, skin, hair, and plastic surgery) participated in the study by convenient sampling regarding ethical considerations, including willingness and informed consent. Information confidentiality and avoiding damaging the participants were emphasized. The inclusion criteria were gender (female), the time certainty of the cosmetic surgery by a specialist through the next month by passing medical procedures, not having a history of psychological problems, including mood disorders, anxiety, and personality disorders, or being hospitalized and not using psychiatric medication, previous history of rhinoplasty in the last one year at least, demand to perform it again or more than twice for rhinoplasty or other types of cosmetic surgery, having at least a diploma, resident of Kermanshah, and at least 18 years old to 60 years old. As a result of these criteria, any applicant without a cosmetic reason for surgery was deprived, or even those who gave up completing the questionnaires for any reason during the research. The participants were tested with Revised Adult Attachment Questionnaires (RAAS), Young’s early maladaptive schemas questionnaire (75 questions), and the symptom scale of psychological disorders (R-90-SCL). The data were collected with SPSS software version 22 and analyzed with LISREL 8.8. The reliability and validity of the tools are as follows:

3.1.1. Adult Attachment Questionnaires

This questionnaire contains 18 items, in which the participant’s score is determined for each subscale based on the Likert scale. Collins and Read (23) showed that the closeness, dependence, and anxiety subscales remained stable for two and even eight months. Six scale scores were collected, and the subscale score was obtained. The lower score is 0, and the higher score is 72. Regarding the reliability of the adult attachment scale, Collins and Read showed that Cronbach’s alpha level for each subscale of this questionnaire is equal to or more than 0.80 in three sample students, and the test has high reliability. In the present study, the questionnaire reliability was obtained through Bartlett’s trial, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was equal to 0.89 for all questions of this questionnaire, which shows high reliability.

3.1.2. Early Maladaptive Schemas Questionnaire

The early maladaptive schemas questionnaire was created by Young (20). The scale reliability was reported as 0.96 for the whole test and higher than 0.80 for all subscales (24). The scoring method is based on a six-item Likert scale ranging from entirely false = 1 to completely true = 6. Five scale scores are collected, and the subscale score is obtained. The lower score is 75, and the Higher score is 450. Hamidpour (13) reported the scale reliability by Cronbach’s alpha for all scales in the range of 0.62 to 0.90. The internal consistency of this questionnaire is 0.94, which indicates the high reliability and stability of the scale. The questionnaire reliability coefficient was calculated at 0.70 in the present study based on Cronbach’s alpha.

3.1.3. Scale of Psychological Disorders Symptoms

This questionnaire is the most usable psychiatric diagnostic tool. The original form of the test was prepared by Derogatis et al. (25), and its revised was prepared by Derogatis et al. (25, 26). Levitt and Truumaa (27) evaluated the reliability of the Scale of Psychological Disorders Symptoms (SCL-90-R) questionnaire, calculated Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, and investigated the internal consistency of this test. The alpha coefficients range for decuple subscales was from 0.83 to 0.94, indicating the desirable internal consistency of this questionnaire. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for all questionnaire questions was 0.77.

4. Results

The average age of the participants was 33.5 years, of whom 39.7% were single and 60.3% were married. The education rate was 29.3 diplomas, 8.7 post-graduate, 48.7 bachelor’s degrees, 3.9 post-graduate degrees, and 0.4 doctorates. Rhinoplasty had the highest demand, and skin lift had the lowest demand among applicants’ surgeries (Table 1).

| Variables | Minimum | Maximum | Mean ± SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment styles | 30 | 90 | 58.96 ± 10.11 | 0.207 | 0.334 |

| Early maladaptive schemas | 250 | 342 | 294.08 ± 15.13 | 0.147 | 0.294 |

| Psychopathology | 232 | 326 | 277.07 ± 14.10 | 0.145 | 0.287 |

Examining the results of the data normality test using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test in Table 2 indicates that the data had good normality.

| Psychopathology | ||

|---|---|---|

| Pearson Correlation Coefficient | Significance Level | |

| Attachment styles | 0.559 | 0.009 |

| Early maladaptive schemas | 0.888 | 0.008 |

According to Table 2, the attachment correlation with psychopathology symptoms equals 0.009, indicating a significant positive relationship. There is a significant relationship for the correlation between early maladaptive schemas, and psychopathology is equal to 0.008. This relationship is positive according to the value and sign of the obtained Pearson correlation coefficient, equal to 0.888.

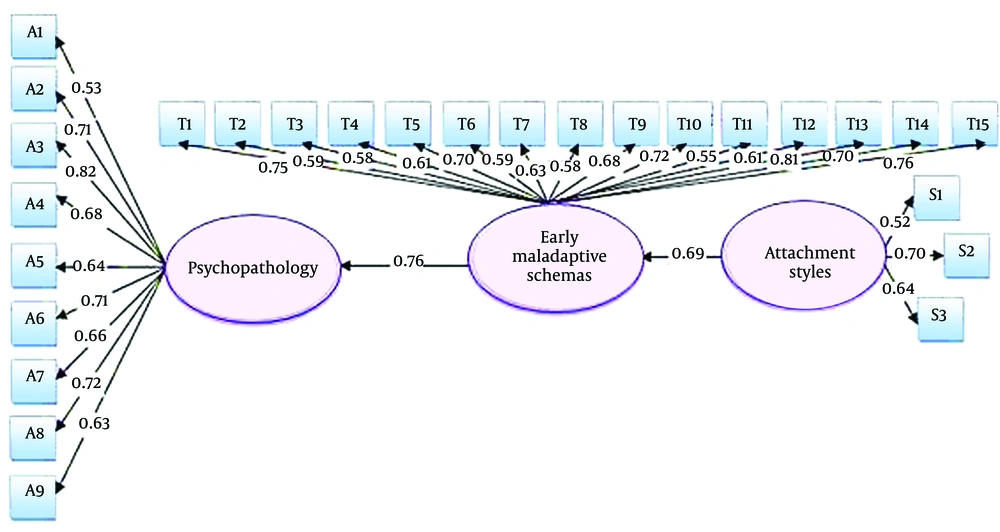

Path analysis was used to test early maladaptive schema’s mediated role in the relationship between attachment styles and psychopathology. The table of unstandardized, standard, and significance levels of direct paths for the hypothetical model shows the role of basic psychological needs in the relationship between attachment styles and psychopathology symptoms. Except for attachment style or styles, the effect of early maladaptive schema on psychopathology was significant.

Table 3 shows direct and indirect effects using structural equation analysis. The variable effect of attachment styles on psychopathology is 0.785. The value of the t-test statistic is 7.167, and its significance level is 0.029 and less than 0.05 (P < 0.05 and t ≥ 3). In addition, the variable effect of early maladaptive schemas on psychopathology is 0.863, the value of the t-test statistic is 9.597, and the corresponding significance level 0.013 is equal to and less than 0.05 (P < 0.05 and t ≥ 3), and this effect is also significant.

| Direct and Indirect Relationships | Effect Size | t-test Statistic | Significance Level | Result of Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment styles | 0.785 | 7.167 | 0.029 | Confirmation |

| Early maladaptive schemas | 0.836 | 9.597 | 0.013 | Confirmation |

In Table 4, the direct effect of the attachment styles variable on psychopathology with the mediation of early maladaptive schemas is 0.524, the value of the t-test statistic is 6.591, and the corresponding significance level is 0.000 and less than 0.05 (P < 0.05 and t ≥ 3). Therefore, this effect is significant.

| Relation | Effect Size | t-test Statistic | Significance Level | Result of Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment styles | 0.524 | 6.591 | 0.000 | Confirmation |

The analysis of the conceptual model based on standard coefficients is as follows (Figure 2):

According to the fit indicators that can be seen in Table 5, the study hypothetical model has a good fit. The ratio

| Indicator | Symbol | Acceptable Range | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| The chi square of the degree of freedom | 2 to 5 | Model confirmation | |

| The root mean square error of approximation | RMSEA | 0.00 to 0.05 | Model confirmation |

| The root mean of remained square | RMR | 0.00 to 0.50 | Model confirmation |

| Goodness of fit | GFI | 0.90 to 1 | Model confirmation |

| Modified goodness of fit index | AGFI | 0.90 to 1 | Model confirmation |

| Normalized fit index (Bentler-Bonet) | NFI | 0.90 to 1 | Model confirmation |

| Comparative fit index | CFI | 0.90 to 1 | Model confirmation |

| Incremental fit index | IFI | 0.90 to 1 | Model confirmation |

Further, the value of the remaining mean root should be less than 0.05, between zero and 0.50, in this model. These indicators show that the presented model is good and matches the experimental psychological data.

5. Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the mediated role of early maladaptive schemas in the relationship between attachment styles and psychopathology in females applying for cosmetic surgery. The results showed that attachment styles directly predict psychological damage. The results match with Linares et al. (12), Lee and Koo (28), Duchesne and Ratelle (29), Kullik and Petermann (30), and Besharat et al. (31). Applicant attachment styles are determinants by emotional and cognitive characteristics to guide the individual emotional reactions and their interpersonal relationships (32). The evolution and organization of these internal representations or models lead to individual differences in psychological health quality (33). According to Bowlby’s theory (10), individuals with insecure-avoidant attachment, whose attachment models are developed based on isolation and distancing strategies, found no reliable source to trust. As a result, conflicts increase, and people feel more independent since they avoid the relationship. Anxious attachments have a negative image of themselves as incompetent, improper of love, and therefore dependent. In addition, these studies have shown that the combination of low self-esteem, low self-efficacy, and ambivalence in relationships can easily lead to the internalization of symptoms such as anxiety and depression (31). Moreover, individuals with an avoidant attachment style pay less attention to feelings and emotional events than ambivalent or secure people (32), and they pay more attention to cognitive factors than emotional factors in planning their behavior (34). Therefore, the result of these defenses is divided into psychological systems (35), which cause problems in the individual’s psychological health and general functioning. The information processing theory states that blocked and unexpressed emotions cause psychological damage. In addition, the results showed that early maladaptive schemas directly predict psychopathology. These results were consistent with Patel et al. (36) and Shahamat (37). Switzer (38) believes that schemas are the deepest cognitive structures. According to Beck, the schema is a cognitive structure for selecting, decoding, and evaluating the stimuli that affect the organism (39-41). Individuals whose schemas are impaired limits, their internal limits regarding mutual respect and self-restraint have not developed enough. The impulses they exhibit cannot be controlled, nor can they delay satisfying their immediate needs so that they can reap future benefits. A person with insufficient self-control/self-discipline cannot show self-control and tolerate failure sufficiently to achieve their goals. On the other hand, emotions and impulses cannot be controlled. This schema place too much emphasis on avoiding discomforts, which does not try to create conflict in interpersonal relationships and avoid accepting more responsibilities. In addition, individuals in over-vigilance areas suppress their emotions and spontaneous impulses. Despite losing happiness, self-expression, peace of mind, intimate relationships, or health, they often follow their internalized rules (15). Individuals with an emotional inhibition schema limit their spontaneous behaviors, emotions, and interpersonal relationships and usually do this to avoid criticism or losing control over their impulses. The most common areas of inhibition are (1) inhibition of anger, (2) prevention of positive impulses such as jokes, affection, positive excitement, and playfulness, (3) difficulty in expressing vulnerability, and (4) emphasis on rationality and ignoring emotions, so these persons seem boring, restricted, isolated or cool and heartless (42). Therefore, all cases can cause many psychological disorders. In addition, the results indicated that the hypothetical model of study fits well with the experimental data. The path analysis showed the mediated role of early maladaptive schema in the relationship between attachment styles and psychopathology. These findings matched those of Roelofs et al. (43), Sohrabi et al. (44).

5.1. Limitations

Limitations were the invalid responses and participants’ efforts to present a better image of themselves due to the taboo of psychological damages and reactions to perform cosmetic surgeries, lack of control of some mediator variables effect such as cultural responsibility, participants’ mood characteristics, personality traits, the effect of economic and social class, the role of genetics and issues related to the background of the individual’s evolutionary, the heredity factor and its effect on psychological vulnerability. The study sample only included females applying for cosmetic surgery. Therefore, the results cannot be generalized to male applicants for cosmetic surgery. Thus, the next study should investigate male and non-male applicants for cosmetic surgery.

5.2. Conclusions

Based on the avoidant and anxious attachment styles with a negative effect on an individual’s schemas, increased physical complaints, obsessions, sensitivity in interpersonal relationships, depression, anxiety, aggression, phobias, paranoid thoughts, and psychosis. Young also presented the schema model to describe the relationship between parents and pathology and its theoretical basis based on some studies on attachment theory. A potential mediator in parental relationships and the occurrence of children’s pathology is creating early inefficient or negative formalized beliefs in children. Bowlby‘s attachment theory showed the potential relationship between insecure attachment styles, schemas, and psychological disorders. Negative interactions with early caregivers in early life create early maladaptive schemas and cause individuals to be psychologically vulnerable and have cognitive problems when faced with stress. Beck believes that cognitive schemas caused by past experiences create emotions and behaviors and affect the world’s perception. These results indicated that the applicant’s needs for cosmetic surgery had not been consistently satisfied for security, support, health, and acceptance, and these persons received less attention, warmth, and companionship from others and had not a source of strength and support to reach this source of support, so they have had cosmetic surgery. Eventually, the variables of attachment styles and early maladaptive schemas can predict psychopathology in females applying for cosmetic surgery. Therefore, planning for psychological consultation and referring some individuals who obsessively apply for cosmetic procedures without medical reasons and requirements can be a process for cosmetic surgery to prevent, diagnose and treat psychological damages and improve an individual’s psychological health. It should also be noted that this study has its limitations, like all self-reported studies.