1. Background

Couples start their marital journey with a strong sense of affection but eventually notice a gradual decline in their initial level of intimacy. Over time, particular couples may experience separation, while most persist in their marriage with a boring and uneventful routine. Some individuals may resort to alcohol consumption, overeating, drug use, or engaging in extramarital affairs to cope with this situation. The primary incentive for married individuals who are inclined towards extramarital relationships is the desire to rekindle personal and sexual intimacy. Therefore, the attractiveness of these recently established relationships arises from the lack of fault-finding, blame, complaints, or nagging exhibited by either party (1). Infidelity is typically characterized as engaging in sexual activities with an individual who is not one's current partner (2). Contemporary academic literature has broadened the scope of infidelity, which is also referred to as "unfaithfulness" and "cheating," to encompass emotional behaviors as well. This expanded definition has been acknowledged by various scholars (3, 4). Emotional infidelity refers to the establishment of an intimate emotional bond with an individual who is not one's current partner. As a result of concealing these activities, infidelity is considered a form of betrayal because it involves a clandestine relationship with an individual other than one's primary partner (5).

Multiple factors can contribute to people engaging in extramarital relationships. Identifying these factors is crucial in taking the initial step toward preventing such betrayals in committed relationships. A study found that males with extramarital relationships were more dissatisfied with their married sexual relationships than women. Women choose emotional love, while men want sexual relationships due to gender stereotypes and gender conditioning (6). Several studies have linked extramarital relationships to men's sexual satisfaction. This association is either absent in women or more substantial in men (7).

Attachment theory helps explain how people develop personalities and negotiate intimate relationships (8). According to a study, attachment style may predict infidelity (9). Securely attached individuals are less likely to have extramarital affairs (10-12). Avoidant attachment styles may increase one's partner's bitterness and argumentativeness to justify their infidelity (12, 13). Adults with poor early emotional ties may struggle to form lasting emotional bonds. DeWall et al. found that avoidant people are uncomfortable with psychological closeness and intimacy. Avoidant attachment style partners have trouble forming deep emotional bonds, which lowers commitment. Low commitment levels may lead to infidelity (12, 14). People with a higher avoidant attachment style are less likely to view infidelity as a problem (12). Emotional infidelity may be more common in people who did not learn to maintain emotional bonds, especially when they saw their primary caregivers as unfaithful (15).

Personality is another crucial factor in understanding people's participation in marital relationships. Studies have shown that the Big Five personality factors are associated with infidelity. Research has demonstrated that individuals who engage in infidelity are likely to score higher than non-betrayers on neuroticism (16-18), openness and extraversion (13, 16, 19), and lower on agreeableness and conscientiousness (13, 16, 17, 19). However, contradictory evidence was found linking personality traits to cheating, especially openness and extroversion. Some research has indicated a positive relationship with infidelity (13, 19), some negative (17, 20), and others found no relationship (16, 17). Extraversion was also related to infidelity in certain research (13, 19, 20) but not in others (16, 17).

Another important factor involved in the tendency toward infidelity is sexuality. Sexual issues have been found to underlie cheating relationships in several research (21). Sexual satisfaction drives this predisposition toward extramarital affairs and typically stems from marital issues, which can cause marital resentment, shame, and jealousy and make both couples feel insecure and competitive. Relationship conflicts can worsen these concerns. According to recent studies, sexual reasons and marital sexual unhappiness may cause individuals to engage in extramarital relationships (22, 23).

Apart from the inconsistent results in this field, which prompted us to investigate the mediating factors between personality dimensions and cheating, it is also essential to mention that cheating leaves a lasting impact on individuals and their environment. Infidelity emerges as a prevalent issue among couples seeking therapy, as reported by 122 marital therapists (24). Infidelity is frequently cited as a contributing factor to marital breakdown (25). Over 50% of divorced couples have reported instances of prior infidelity (26). In addition to its correlation with divorce and marital discord, it has been observed that infidelity, whether confirmed or suspected, serves as the primary catalyst for instances of domestic violence and spousal murder (13). Researchers studied male sexual jealousy and its relationship with male homicides in Detroit, examining cases in which jealousy served as the motive for murder. There were a total of 306 murders recorded within one year, and 40 of them involved allegations of infidelity or sexual rivalry. Children who have become aware of a parent's act of infidelity are faced with the task of comprehending and interpreting their parents' behavior, potentially at an age when they lack the necessary cognitive and emotional maturity. In addition, parents may also be required to withhold information from the other parent, thereby engaging in an unhealthy breach of boundaries within the family unit, which can potentially lead to the development of anxiety in children (27). Parental infidelity poses a significant risk to the stability and security of the family unit, which in turn has a profound impact on the healthy psychological development of children (28).

2. Objectives

Given the adverse implications of infidelity on personal well-being, relationship dynamics, and the welfare of children, there is a pressing need for scholarly investigations aimed at elucidating the various factors contributing to individuals' inclination towards extramarital involvement. Hence, the primary objective of the present study is to examine the interconnections among personality traits, attachment styles, and levels of marital satisfaction to predict the inclination of couples to engage in infidelity.

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling

This fundamental study employed a descriptive-correlational approach and structural equation modeling. The population consisted of male and female individuals seeking counseling services at centers located in Mashhad. Given the focus of the current investigation on the inclination towards engaging in extramarital relationships, there were no specific limitations imposed on the selection of male and female participants seeking counseling services in Mashhad to comprise the sample group. The research sample was chosen using the multi-stage cluster sampling technique. Initially, two areas were randomly selected from the various regions of Mashhad. Subsequently, ten counseling and psychological service centers were randomly chosen from the areas mentioned above. A total of 220 individuals, comprising 22 individuals from each center, were selected randomly from both male and female populations seeking psychological and counseling services related to marital concerns at these centers. The research topic was discussed with the selected participants to ensure ethical practices and obtain informed consent. Participants who refused to participate were respectfully replaced with another individual. An additional 20 individuals were included in the sample to ensure the sample size did not fall below 200 people. The purpose was to account for any incomplete questionnaires received.

3.2. Instrumentation

3.2.1. The Attitude Toward Infidelity Scale

Whatley (2006) developed this scale, and Abdullahzadeh (2012) standardized it in Iran (29). Each of the 12 statements is scored on a seven-point scale from strongly disagree (scoring 1) to agree (scoring 7) strongly. The most excellent score is 48, suggesting acceptance of infidelity, and the lowest is 12, signifying rejection. Infidelity is neither accepted nor rejected by a person with a score of 48. This scale's Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.84 in a sample of 383 single and married men and women. This scale can be used for survey research and to uncover factors and variables that affect extramarital relationships and attitudes toward infidelity (29).

3.2.2. The Revised NEO Personality Inventory

The questionnaire (NEO PI-R) was initially developed in 1985 by McCree and Costa (cited in Ghaffariyan Roohparvar et al.), which consisted of two distinct forms denoted S and R. Each form comprised a total of 240 questions (23). In addition, the researchers developed a brief form that contained 60 items, each scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to agree strongly. The shorter version of this assessment tool was designed to assess the main elements of typical personality traits (30). Research demonstrated that a shorter questionnaire form exhibits a strong correlation (0.68) with its full-length counterpart, indicating favorable validity (30). The test's reliability coefficient was found to range from 0.75 to 0.83 using the test-retest method, reported by McCree and Costa. Additionally, the test demonstrated internal consistency in a 6-year study, with coefficients ranging from 0.68 to 0.83 (23).

3.2.3. The Revised Hazan and Shaver Three-Category Measure

This study utilized the Revised Three-Category Measure developed by Hazan and Shaver (31) to assess the adult attachment styles. The scale was later standardized in Iran by Rahimian Bougar (32). The scale consists of 15 items, each of the three attachment styles (secure, avoidant, and ambivalent) represented by five items. In their study, Collins and Reed used factor analysis to identify three primary attachment factors: Secure, avoidant, and ambivalent, commonly understood by researchers as indicators of an individual's ability to form and maintain intimate and close relationships. Research has reported the overall retest reliability of the questionnaire to be 0.81, while the reliability assessed using Cronbach's alpha yielded a value of 0.78 (33). A study reported that Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficients for the ambivalent, avoidant, and secure style subscales were 0.75, 0.83, 0.81, and 0.77, respectively (32).

3.2.4. Index Of Sexual Satisfaction Scale

The Index of Sexual Satisfaction Scale was employed to assess levels of sexual satisfaction. The present questionnaire comprises a total of 25 self-report questions. These questions are structured in a seven-point Likert scale format, requiring respondents to rate their responses on a scale ranging from 0 to 6. A score of 0 indicates a response of "never" on this scale, while a score of 6 represents a response of "always." The overall score of the questionnaire ranges from 0 to 150. The questionnaire's validity was assessed by determining its correlation with the sexual satisfaction subscale of the enrich Inventory, yielding a coefficient of 0.74. The instrument's reliability was determined to be 0.95 based on a test-retest conducted over a 15-day interval. This value indicates a high level of reliability, suggesting that the tool can be considered highly reliable. The split-half technique was also employed to conduct a more comprehensive analysis of the obtained credibility, yielding a reliability coefficient of 0.88 (34).

4. Results

Out of the 200 individuals who participated in this study, 86 were men, 43%, and 114 were women, 57%. Five individuals (2.5% of the participants) have less than a high school diploma, 23 individuals (11.5% of the participants) have a high school diploma, 85 individuals (42.5% of the participants) have a bachelor's degree, 67 individuals (33.5% of the participants) have a master's degree, and twenty individuals (10%) have a Ph.D. Most of the sample were women and had at least a bachelor's degree. The proposed model recommends selecting a minimum sample size of 20 individuals for each variable. The current research model consists of four variables, requiring a minimum sample size of 80 individuals for implementation. The assumption has been met in the present study, as the sample consisted of 200 people (35, 36). The Durbin-Watson statistic for the predictor variables was 1.502. The device operates at the optimal level of efficiency based on this value. Therefore, the assumption of independent errors is valid. The variance inflation factor (VIF) helps assess multicollinearity among the independent variables in a multiple regression model (37). Based on the low VIF values observed for all independent variables, which are close to 1, the assumption of non-collinearity between independent variables has been satisfied. In the following, the proposed model is presented.

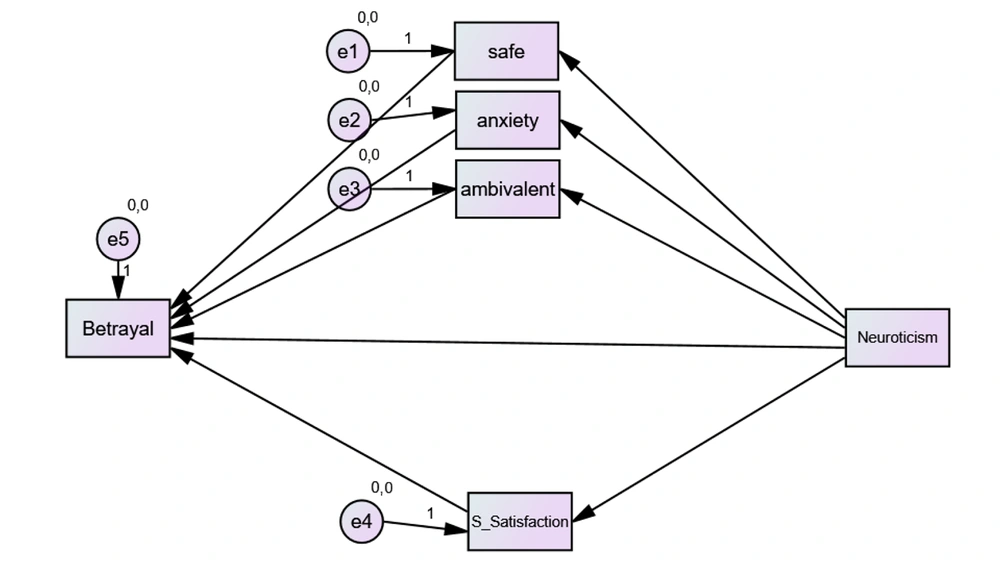

The study used path analysis conducted through AMOS software to examine the relationship between neuroticism, attachment styles, sexual satisfaction, and the tendency to engage in infidelity. In this model, neuroticism is considered as an exogenous (independent) variable. Attachment styles and sexual satisfaction are defined as endogenous (mediator) variables, while the tendency to engage in infidelity is defined as an endogenous (dependent) variable.

The fit indices for the model based on neuroticism are presented in Table 1. The initial model developed by the researcher (Figure 1) did not demonstrate a good fit. As a result, the model was modified to achieve better-fit indices. The modification was completed in two steps. The first step involved removing the one-way path of neuroticism, anxious attachment style, ambivalent attachment style, and tendency to betrayal. The second step involved adding the two-way error path of secure attachment style measurement error to the ambivalent attachment style measurement error. Additionally, the two-way error path of the ambivalent attachment style measurement error was added to the sexual satisfaction measurement error. As a result, the modified model achieved optimal fit indices.

| Indices | Threshold | Default Model | Modified Model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism→Anxiety Removed; Neuroticism→Ambivalent Removed; Neuroticism→Betrayal Removed | e1↔e Added; e4↔e3 Added | |||

| Parsimonious fit indices | ||||

| NPAR | - | 21 | 18 | 20 |

| CMIN | - | 29.456 | 34.83 | 13.689 |

| DF | - | 6 | 9 | 7 |

| P | - | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.047 |

| CMIN/DF | 1 - 5 | 4.9.9 | 3.789 | 1.96 |

| RMSEA | < 0.07 | 0.140 | 0.119 | 0.069 |

| Comparative fit index | ||||

| CFI | > 0.90 | 0.806 | 0.789 | 0.94 |

| NFI | > 0.90 | 0.783 | 0.748 | 0.90 |

| IFI | 0 - 1 | 0.8.6 | 0.801 | 0.95 |

Fit Indices of the Model of Marital Infidelity Tendency Based on Neuroticism with the Mediation of Attachment Styles and Sexual Satisfaction

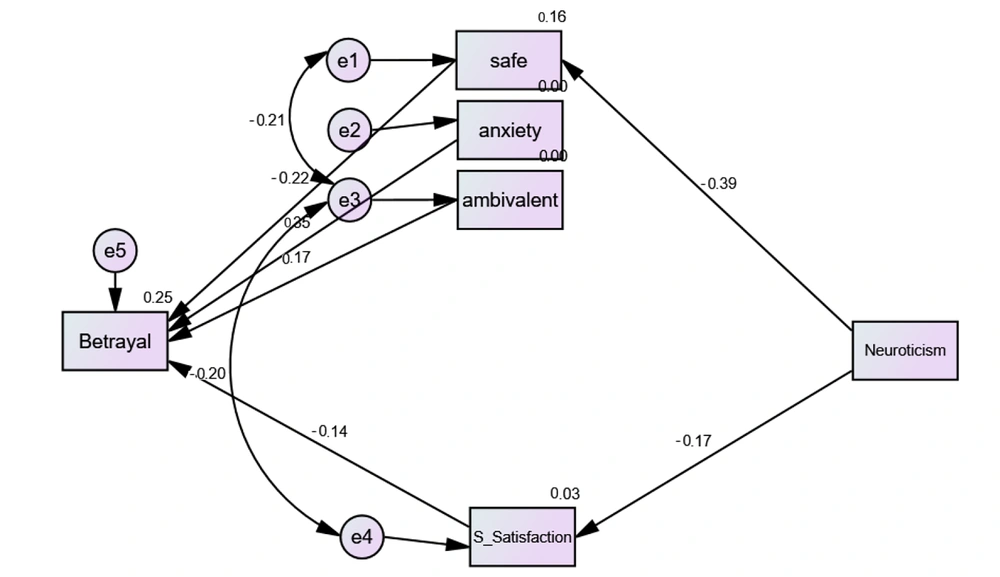

The final model strongly fits absolute, parsimonious, and comparative fit indices. Figure 2 displays the fitted model after removing the proposed paths and adding new paths. Neuroticism, with an indirect effect of 0.110, has only an indirect effect on a tendency to betray through secure attachment and sexual satisfaction. In addition, each of the four mediating variables, namely secure attachment, anxious attachment, ambivalent attachment, and sexual satisfaction, has a direct effect on the propensity for infidelity, with respective direct effects of -0.222, 0.346, 0.174, and -0.136. The authors faced constraints regarding the number of tables and the word limit. Consequently, modified models were presented, accompanied by an analysis of fit indices and an examination of direct and indirect effects. However, the specific tables containing this information are not explicitly mentioned due to space limitations.

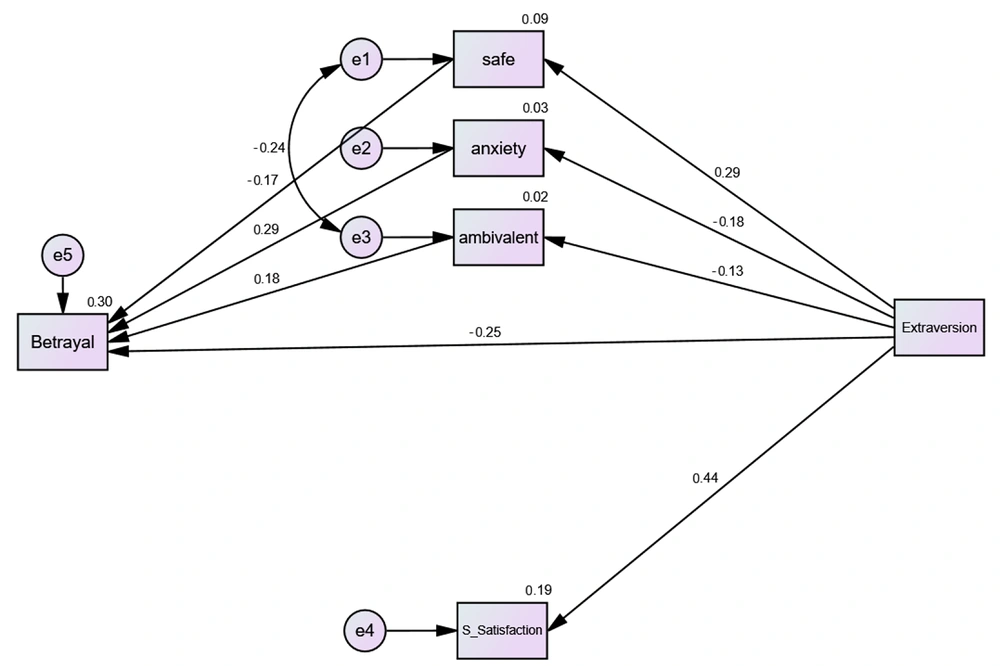

The fit indices were derived in the preliminary analysis, including the chi-square value (P = 0.003, NPAR = 21, and CMIN = 15.738), Bentler's comparative fit index (CFI = 0.936), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.133). Despite the significant value of the chi-square statistic, the obtained values suggest that the model does not exhibit a satisfactory fit. Consequently, modifications were made to enhance the model's fitting. The modification was completed in two steps. The first step involved removing the one-way path from extroversion to anxious attachment style, as well as the one-way path from sexual satisfaction to the tendency to infidelity. In the second step, the measurement error of the secure attachment style and its impact on the measurement error of the ambivalent attachment style in the model were included. This modification achieved the desired fit indices for the model. Figure 3 shows that extraversion significantly affected the tendency to engage in infidelity, which is observed directly, with a coefficient of -0.263, and indirectly through the three attachment styles: Secure, anxious, and ambivalent. The three styles of attachment -secure attachment, anxious attachment, and ambivalent attachment- have different effects on the tendency to engage in infidelity. Specifically, the effect sizes are -0.174, 0.293, and 0.183, respectively. In the modified model, the fit indices were derived, including the chi-square value (P = 0.003, NPAR = 21, and CMIN = 27.190), Bentler's comparative fit index (CFI = 0.860), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.07).

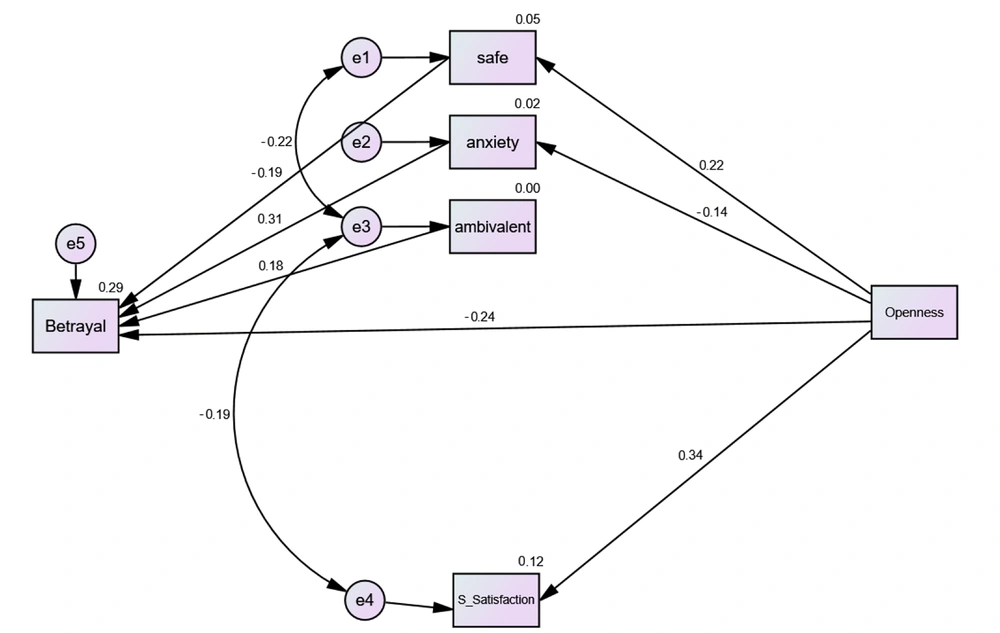

In the preliminary analysis, the fit indices were derived, including the chi-square value (P = 0.000, NPAR = 21, and CMIN = 28.231), Bentler's comparative fit index (CFI = 0.828), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.137) (Figure 4). Despite the significant value of the chi-square statistic, the obtained values suggest that the model does not exhibit a satisfactory fit. Consequently, modifications were made to enhance the model's fitting in two steps. The researchers eliminated the unidirectional relationship between sexual satisfaction and cheating tendency and the unidirectional relationship between openness and ambivalent attachment style in the first step. In the next step, the model was enhanced by incorporating a bidirectional relationship between measurement error in secure attachment style and measurement error in ambivalent attachment style and a bidirectional relationship between measurement error in ambivalent attachment style and measurement error in sexual satisfaction. The modified model demonstrated optimal fit indices as a result of these modifications. The effect of openness on the tendency to engage in infidelity is observed directly, with a coefficient of -0.141, and indirectly through secure and anxious attachment styles, with a coefficient of -0.86. The direct impact of three attachment styles, namely secure attachment, anxious attachment, and ambivalent attachment, on the tendency to engage in infidelity were observed to be -0.191, -0.309, and -0.185, respectively. In the modified model, the fit indices were derived, including the chi-square value (P = 0.04, NPAR = 21, and CMIN = 12.722), Bentler's comparative fit index (CFI = 0.948), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.07).

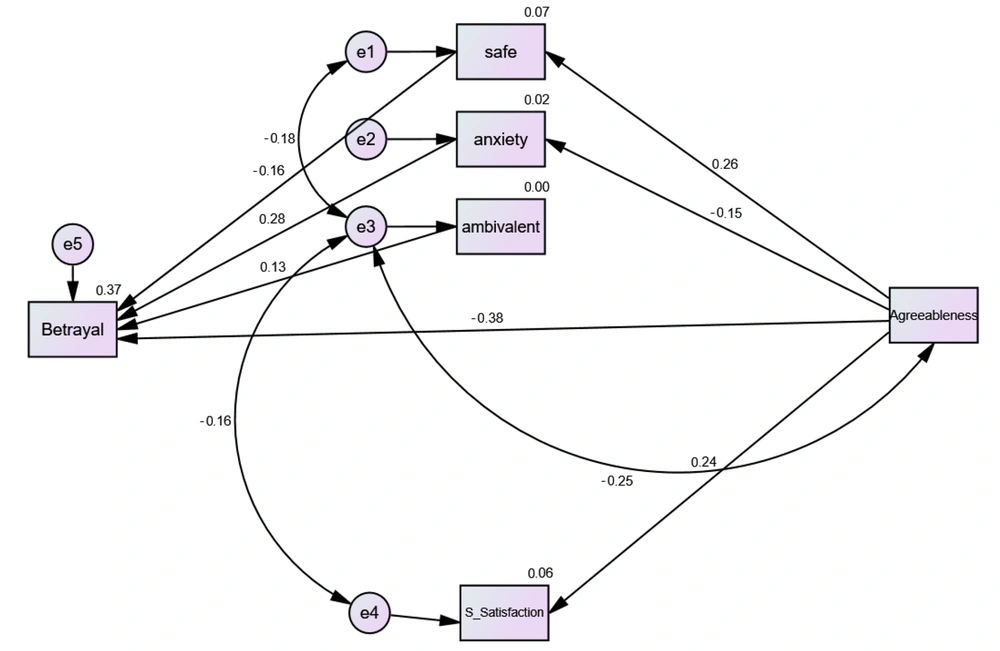

In the preliminary analysis, the fit indices were derived, including the chi-square value (P = 0.000, NPAR = 20, and CMIN = 38.318), Bentler's comparative fit index (CFI = 0.782), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.150) (Figure 5). Even though the chi-square statistic is significant, the obtained values suggest the model is not satisfactorily fitted. Consequently, modifications were made to enhance the model's fitting in two steps. The first step involved the elimination of the unidirectional relationship between sexual satisfaction and a tendency to engage in infidelity. In the subsequent stage, the model incorporated two-way paths: One linking secure attachment style measurement error to ambivalent attachment style measurement error, another linking ambivalent attachment style measurement error to sexual satisfaction measurement error, and a third linking ambivalent attachment style measurement error to agreeableness. Thus, the modified model successfully achieved the desired fit indices.

The effect of agreeableness on the tendency to engage in infidelity is observed directly, with a coefficient of -0.376, and indirectly through secure and anxious attachment styles, with a coefficient of -0.84. The direct impact of three attachment styles, namely secure attachment, anxious attachment, and ambivalent attachment, on the tendency to engage in infidelity were observed to be -0.165, 0.282, and -0.127, respectively. In the modified model, the fit indices were derived, including the chi-square value (P = 0.02, NPAR = 22, and CMIN = 12.711), Bentler's comparative fit index (CFI = 0.946), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.07).

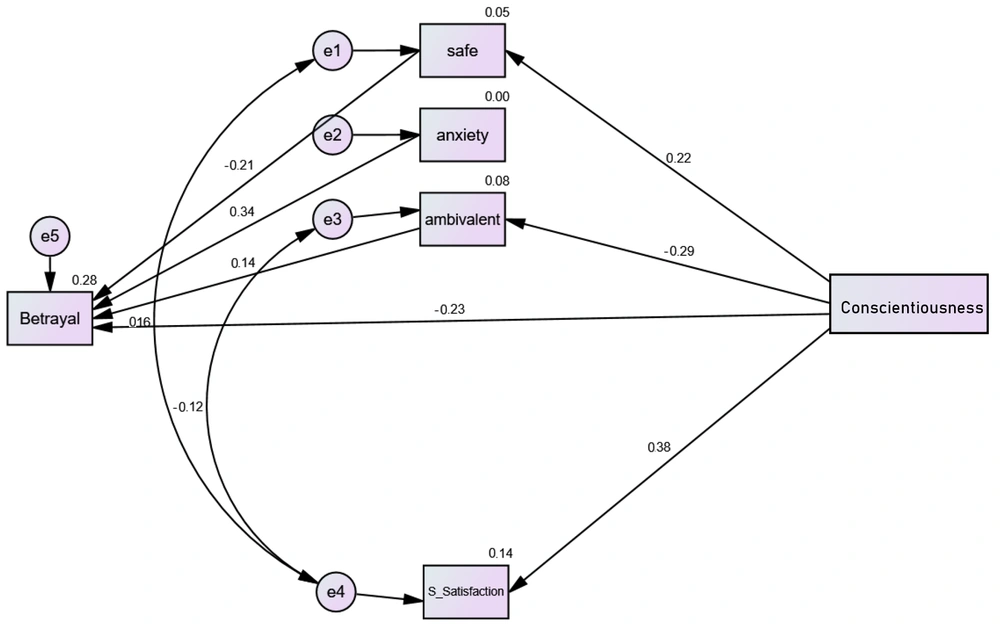

The fit indices in the preliminary analysis included the chi-square value (P = 0.002, NPAR = 21, and CMIN = 20.526), Bentler's comparative fit index (CFI = 0.889), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.110) (Figure 6). Despite the significant value of the chi-square statistic, the obtained values suggest that the model does not exhibit a satisfactory fit. Consequently, modifications were made to enhance the model's fitting in two steps. The initial phase involved excluding the unidirectional relationship between conscientiousness and anxious attachment style and the unidirectional relationship between sexual satisfaction and the tendency to engage in infidelity. In the subsequent phase, the model was enhanced by incorporating two-way paths: One from secure attachment style measurement error to ambivalent attachment style measurement error and another from secure attachment style measurement error to sexual satisfaction measurement error. This modification resulted in the modified model displaying optimal fit indices.

The effect of conscientiousness on the tendency to engage in infidelity is observed directly, with a coefficient of -0.229, and indirectly through secure and ambivalent attachment styles, with a coefficient of -0.84. The direct impact of three attachment styles, namely secure attachment, anxious attachment, and ambivalent attachment, on the tendency to engage in infidelity were as much as -0.213, 0.145, and -0.340, respectively. The fit indices in the modified model included the chi-square value (P = 0.04, NPAR = 21, and CMIN = 11.917), Bentler's comparative fit index (CFI = 0.955), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.07).

5. Discussion

The present study employed five distinct models to examine the impact of personality traits on the likelihood of engaging in extramarital relationships. A separate examination was required due to the non-cumulative nature of personality trait scores. The findings suggest that neuroticism influences the inclination to engage in extramarital relationships, albeit indirectly, through the mediating factors of secure attachment style and sexual satisfaction. However, a direct impact of neuroticism was not observed on the propensity for extramarital relationships. The trait of extraversion has both direct and indirect effects on the inclination towards engaging in extramarital relationships, with attachment styles serving as a mediating factor. There was a significant relationship between secure attachment style and sexual satisfaction, which in turn contributes to a negative correlation between extraversion and extramarital relations. The personality trait of openness had a direct and indirect impact on the inclination towards engaging in extramarital relationships, mediated by both secure and anxious attachment styles and sexual satisfaction. The observed relationships exhibited a notable pattern, wherein openness was significantly and inversely associated with the inclination towards extramarital relationships. Furthermore, this inverse relationship was also observed indirectly through three variables: Secure attachment style, anxious attachment style, and sexual satisfaction. The results obtained were consistent with those about the trait of agreeableness. Ultimately, conscientiousness, directly and indirectly, impacts the inclination toward extramarital relationships, mediated by secure and avoidant attachment styles and marital satisfaction. The findings of this study were consistent with previous studies (9, 38-40). The importance of personality factors in marital relationships cannot be overstated when explaining these findings. Individuals' idiosyncrasies and psychological histories can significantly influence their experiences in marriage, due to their idiosyncrasies. One's marital relationship can be influenced by various factors, including a history of acquired behaviors that enhance or undermine the relationship. Personality issues are frequently identified as the primary determinants impacting marital satisfaction and giving rise to marital problems, as evidenced by numerous research studies. Multiple empirical studies have confirmed that this particular factor significantly affects the likelihood of engaging in extramarital relationships.

However, personality factors can affect attachment styles. Trust, communication, and interpersonal interactions are all influenced by personality attributes, which may affect attachment types and cause changes. Indeed, personality features influence people's perceptions of interpersonal interactions, starting from early childhood, resulting in different attachment styles. Attachment types can affect people's relationship adherence by changing their perception of the connection. Simply said, those with a solid attachment style and who believe their marriage can fulfill their requirements are less likely to have extramarital affairs. This propensity endures despite interpersonal mistrust and fear of relationship loss, which might lead people to switch partners and have extramarital encounters (41-43).

Multiple research has shown that high neuroticism, anxiety, hostility, depression, low self-esteem, fast life pace, and vulnerability diminish sexual satisfaction. Lack of intimacy due to poor communication is a significant cause of sexual dissatisfaction. Extroversion can also boost sexual satisfaction by increasing sexual awareness and encouraging satisfying sexual partnerships with many social connections. These people value socializing over other obligations, and their sexual arousal is increased. These characteristics improve sexual attitudes and fulfillment. Openness also encourages people to listen to their partners and have meaningful sexual dialogues. Understanding their partner's perspective might boost sexual happiness for both partners. Seeking agreement helps people seem more socially desirable and mentally healthier. Since they want closer relationships, this issue boosts sexual attraction and enjoyment. Conscientiousness predicts sexual relationship quality and happiness. Conscientiousness predicts marriage stability and trust. Couples' personalities often affect their sexual enjoyment. Sexual satisfaction is known to influence adulterous partnerships. Sexual dissatisfaction might reduce the urge for extramarital partnerships (44-46).

5.1. Limitations

Due to the study's limitations, generalizations should be made with caution. In this study, the statistical population is the main limitation. Despite the researcher's efforts to carefully select the statistical population to maximize generalizability, the conclusions of this study can only be applied to the sample population. Investigations should include larger populations to strengthen the findings. This study is further limited by self-assessment questionnaires and related limitations. The preciseness and comprehensiveness of data collected by self-assessment questionnaires are acknowledged to be challenging. The study variables did not adequately capture the complete range of factors influencing extramarital partnerships. Some variables should be excluded to limit the study's scope. Therefore, this omission may weaken research explanations. The researcher suggests adding variables to the model to improve comprehension and provide more robust explanations in future investigations.

5.2. Conclusions

Based on the results, personality factors influence extramarital relationships directly and indirectly, which can be used in premarital therapy to educate couples. The inclusion and evaluation of certain factors should be considered in the marriage training and intervention processes. Addressing these factors makes it possible to decrease the likelihood of encountering problems in marital relationships. Given the importance of studying marital relationship data in a dyadic context, the researcher suggests gathering data in a way that can be thoroughly explained within a couple framework. In future research, researchers may be able to better understand variable interactions by using more robust experimental designs.