1. Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune inflammatory disease of the central nervous system (CNS) characterized by progressive demyelination (myelin loss) and subsequent neurodegeneration (neuronal damage) (1). Multiple sclerosis is the most common inflammatory CNS disorder diagnosed in young adults, with a peak incidence around 30 years of age. The majority of patients experience relapsing-remitting MS, characterized by episodes of neurological dysfunction followed by periods of partial or complete recovery (2, 3). Globally, MS affects an estimated 2.8 million individuals, posing a significant psychological burden on both patients and society (4). In addition, the prevalence of MS has been increasing worldwide, including in Iran, over the past five decades (5).

Psychological distress is among the major factors that worsen MS and significantly impact the quality of life for individuals living with the condition. Multiple sclerosis encompasses a range of unpleasant emotional and psychological states, including depression, anxiety, and stress (6, 7). Studies have reported that depression is particularly prevalent in MS, affecting up to 50% of patients, about three times higher than the general population (8). According to estimates, roughly half of those diagnosed with MS depression suffer from anxiety disorders (9, 10). These emotional burdens can exacerbate physical symptoms and contribute to social isolation, creating a negative feedback loop that worsens overall well-being (11, 12). Furthermore, distress tolerance is defined as the capacity to experience and contend with negative psychological states (13, 14).

Rumination is another factor that affects MS, which is the focused attention on a thought and/or subject and a class of conscious thoughts revolving around a common instrumental theme (13, 14). The recurring thoughts involuntarily enter consciousness and deviate attention and objectives (15). Rumination is a set of repetitive passive thoughts focused on the causes and effects of symptoms that prevent adaptive solutions and raise negative thoughts (16). A patient's ruminations may constitute the cognitive foundation, including endlessly replaying thoughts, causing worry about the future and negative self-evaluations, affecting creation and motivation (17).

Considering the difficulty and expense of MS treatment, several psychological and medication interventions have been used for the control and reduction of MS symptoms (18). Earlier works have investigated the effectiveness of various therapeutic approaches, including cognitive-behavioral approaches, emotional schema therapy, and supportive schemas for individuals and groups (19, 20). Self-compassion therapy is a growing field of psychological intervention that has shown promise in alleviating symptoms of various mental health conditions (21). Self-compassion therapy teaches individuals to accept their painful feelings rather than avoid them (22) to realize their experiences and become compassionate. Compassion refers to admitting that not all pains can be resolved or treated, but all pains can be relieved compassionately (23, 24).

Omidian et al. (25) demonstrated that self-compassion therapy could enhance distress tolerance and improve communication beliefs in women with a drug-dependent husband. Ardeshirzadeh et al. (26) showed that acceptance and commitment therapy and self-compassion therapy can diminish automatic negative thoughts and loneliness in divorced women. Abad and Haroon Rashidi (27) reported that self-compassion therapy reduces existential anxiety and rumination in patients. Aghalar and Akrami (28) concluded that the compassion-based scheme provided for mothers with mentally retarded children enhanced their self-compassion and reduced their rumination and depression compared to the control group. Mousavi et al. (29) demonstrated that self-compassion therapy significantly enhances distress tolerance and diminished loneliness in female heads of households. Frostadottir and Dorjee (30) indicated that mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and self-compassion therapy reduced rumination and raised mindfulness and self-compassion in clients with depression, anxiety, and stress.

Limited research has explored the effectiveness of self-compassion therapy for women with MS, particularly concerning managing distress tolerance and rumination. While psychological distress is a well-documented consequence of MS, impacting up to 50% of patients (8), existing treatment approaches may not fully address the specific challenges faced by women with the disease. Self-compassion therapy, focusing on self-acceptance and emotional regulation, offers a promising avenue for intervention. The results can be helpful to therapists, particularly therapists of physical disorders with psychological roots, such as MS.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of self-compassion therapy in improving distress tolerance and reducing rumination in women with MS, addressing a gap in the current literature and potentially informing more tailored therapeutic approaches for this population.

3. Methods

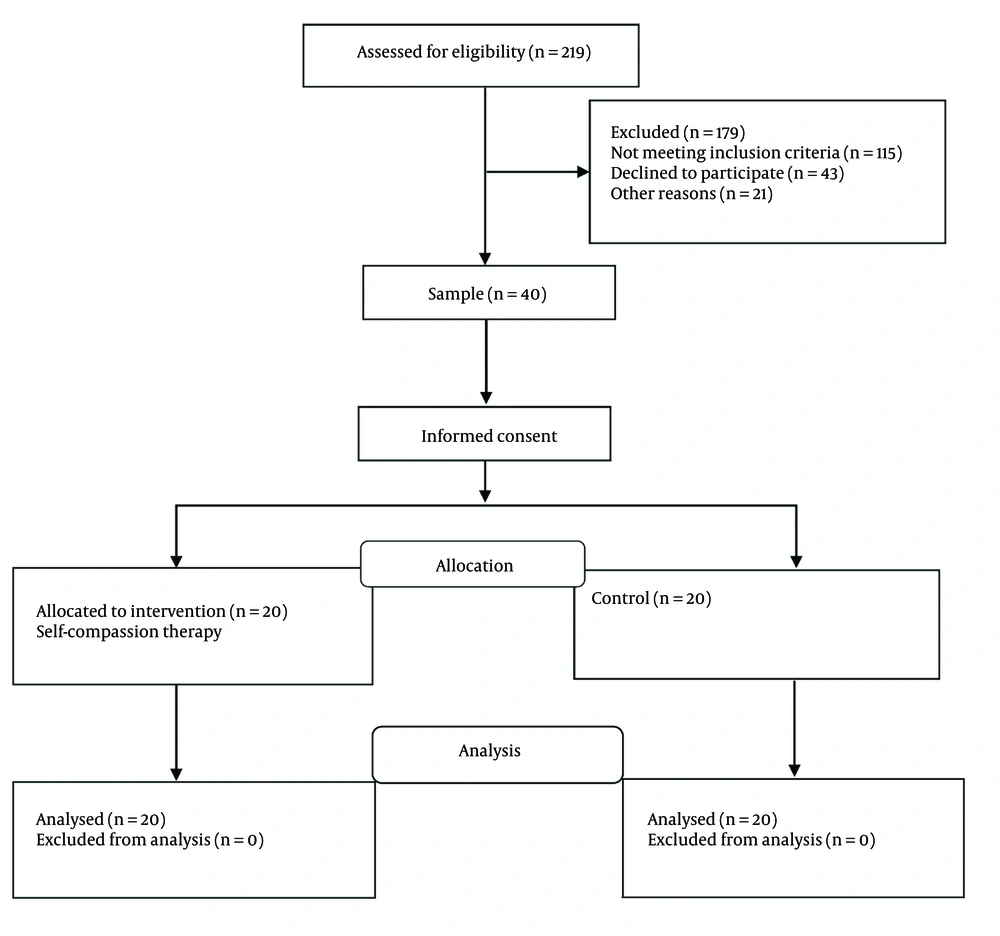

This quasi-experimental study adopts a pretest-posttest design with a control group. The statistical population consisted of all women who went to the MS Society of Ahvaz, Iran, and were diagnosed with MS by a psychotherapist through clinical interviews. These patients attended the MS Society of Ahvaz therapy sessions from November 2022 to January 2023. A total of 71 MS patients were identified through clinical psychotherapist interviews, 40 of whom were randomly selected using convenience sampling and divided into an experimental and a control group with 20 patients (Figure 1). A priori sample size was calculated using G*Power software to ensure sufficient power to detect anticipated effects. The analysis targeted a statistical power of 0.80, a significance level of alpha = 0.05, a large effect size of 0.85, and accounted for a potential attrition rate of 10.0%. The inclusion criteria were being aged 18 - 55 years, having a middle school education or higher, being diagnosed with MS for more than two years, and having no symptoms of major depression or other psychological disorders. The exclusion criteria included having no membership in the MS Society, having other severe psychological disorders, taking psychedelic drugs, using drugs, and failing to participate in sessions. All participants provided written informed consent after receiving a detailed explanation of the study's objectives, procedures, potential risks and benefits, and their right to withdraw at any point. All participant data was anonymized and kept confidential. Each participant will be assigned a unique code to ensure privacy throughout the research process.

3.1. Research Tools

3.1.1. Distress Tolerance Scale

The Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS) is a self-report measure proposed by Simons and Gaher (31) with 15 items and four subscales, including tolerance of distressing emotions, absorption in one's negative emotions, appraisal of capacity and distress experienced, and regulation of emotions. The items are scored on a five-point Likert Scale, where one stands for “totally agree,” while five represents “totally disagree.” The minimum and maximum scores are 15 and 75, respectively. A higher total score would be representative of higher distress tolerance. A Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of 0.77 was obtained for the Persian version of the DTS (32).

3.1.2. Ruminative Response Scale

Ruminative Response Scale (RRS) was developed by Nolen-Hoeksema et al. (33), which evaluates one’s responses to dysphoric mood and consists of two subscales: Reflective pondering and brooding, each with 11 items. The 22 items of the RRS are scored on a four-point Likert Scale, ranging from never (1) to often (4). The RSS has minimum and maximum scores of 22 and 88, respectively. Aghebati et al. (34) reported the reliability of the RRS equal to 0.90 based on Cronbach’s alpha coefficient.

3.2. Intervention Program

Self-compassion therapy sessions: This study designed self-compassion therapy sessions using a compassion-focused therapy package based on Gilbert’s (35) concepts. The intervention was provided in eight 90-minute sessions for the experimental group. The first author, who had completed specialized courses and workshops in self-compassion therapy, delivered the intervention. The control group did not receive the self-compassion therapy intervention during the study period, and they were placed on a waitlist to be offered the intervention after completing the study. Table 1 summarizes self-compassion therapy sessions.

| Session | Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction, pretest, explanation of rules, a brief introduction to compassion and its components, and training and exercise of rhythmic breathing for stress relief; task: Do rhythmic breathing exercises in out-of-session situations |

| 2 | Review of the task and a summary of the previous session, training self-criticism and its types, causes, and effects of self-criticism, methods of reducing self-criticism; task: Evaluate how to respond to one’s self and write down self-critical and self-compassionate thoughts |

| 3 | A brief introduction to the six attributes of compassion (compassion dimensions), including distress tolerance, nonjudgment, sympathy, empathy, compassionate motivation, and sensitivity, and teaching how to withstand and overcome problems; task: Write down examples of compassion dimensions in your life for the next session; daily notes on self-compassion |

| 4 | Introduction to mindfulness and its definition, advantages of mindfulness in life, and teaching mindfulness skills through seated meditation; task: Do seated meditation for mindfulness in out-of-session situations |

| 5 | Teaching how to accept mistakes without judgment, evaluating reasons for not forgiving one’s self and others, reviewing wrong beliefs about forgiveness, and offering solutions for forgiving one’s self and others; task: Do the skill of forgiving yourself or others (ten steps to forgiveness) |

| 6 | Introduction to the power of mental imagery and its correlation with three emotion regulation systems, imagery training and exercise, and providing a secure space for compassionate attributes; task: Do mental imagery exercises to increase self-compassionate thoughts |

| 7 | Introduction to the fear of compassion, explaining the meaning of self-compassionate behavior, and generating ideas for self-compassionate behavior; task: Do something compassionate for yourself or someone else |

| 8 | Writing compassionate letters to one’s self and doing it in the class, conclusion, and posttest |

3.3. Data Analysis

Descriptive and inferential statistics were employed to analyze the data. The mean and standard deviation were used for the descriptive statistics. For the inferential statistics, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to evaluate data distribution normality, Levene's test was employed to assess the equality of variances, and analysis of covariance was utilized in SPSS V.27 to measure the effects of self-compassion interventions on distress tolerance and rumination.

4. Results

No statistically significant differences were observed in demographic characteristics between the experimental and control groups. Age did not differ significantly (P = 0.410), with the self-compassion therapy group averaging 35.81 years old (SD = 5.20) and the control group averaging 37.39 years old (SD = 6.70). Similarly, disease duration showed no significant difference (P = 0.592). The self-compassion therapy group had a mean disease duration of 6.77 years (SD = 2.32), while the control group averaged 7.21 years (SD = 2.80). Educational attainment was also comparable across groups. College education was more prevalent in both groups [n = 10 (66.7%) and n = 8 (43.3%)] in the experimental and control groups, respectively compared to high school education [n = 5 (33.3%) and n = 7 (46.7%)]. Marital status distribution mirrored these trends, with the majority of participants in both groups being married [n = 11 (73.3%) and n = 12 (80.0%)] and a smaller percentage being single [n = 4 (26.7%) and n = 4 (20.0%)].

For the distress tolerance pretest, the mean and standard deviation (SD) were 27.09 and 4.71 in the experimental group and 26.58 and 5.17 in the control group, respectively. In the distress tolerance posttest, the mean and standard deviation were 46.13 and 3.40 in the experimental group and 27.71 and 4.27 in the control group, respectively. In the rumination pretest, the experimental group had a mean of 50.59 and a standard deviation of 4.69, while the control group had a mean of 52.32 and a standard deviation of 5.11. In the rumination posttest, the mean and standard deviation were 35.41 and 3.41 for the experimental group and 53.90 and 5.83 for the control group, respectively (Table 2).

| Variables and Groups | Pretest | Posttest | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distress tolerance | |||

| Experimental group | 27.09 ± 4.71 | 46.13 ± 3.40 | 0.746 |

| Control group | 26.58 ± 5.17 | 27.71 ± 4.27 | 0.001 |

| Rumination | |||

| Experimental group | 50.69 ± 4.93 | 35.41 ± 3.41 | 0.311 |

| Control group | 52.32 ± 5.11 | 53.90 ± 5.83 | 0.001 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test confirmed the null hypothesis that the data had a normal distribution for the distress tolerance and rumination variables (Table 3). Levene's test showed that the variance of the experimental and control groups in distress tolerance and rumination was not significant. As a result, the equality of variances was confirmed.

| Variables and Groups | Pretest | Posttest | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-S | P-Value | K-S | P-Value | |

| Distress tolerance | ||||

| Experimental group | 0.17 | 0.241 | 0.18 | 0.237 |

| Control group | 0.16 | 0.183 | 0.15 | 0.167 |

| Rumination | ||||

| Experimental group | 0.20 | 0.162 | 0.21 | 0.251 |

| Control group | 0.14 | 0.127 | 0.13 | 0.210 |

Abbreviation: K-S, Kolmogorov-Smirnov.

As shown in Table 4, there were significant differences between the experimental and control groups in distress tolerance (F = 31.71, P < 0.001) and rumination (F = 15.12, P < 0.001) in the pretest. The posttest means of the two groups for distress tolerance indicated that self-compassion therapy had significant effects on the improvement of distress tolerance. Furthermore, the pretest revealed a significant difference in rumination between the experimental and control groups (P < 0.001). The rumination posttest means of the two groups indicated that self-compassion therapy significantly reduced rumination in the experimental group (P < 0.001).

| Variables | SS | df | MS | F | P | η2 | Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distress tolerance | 527.45 | 1 | 527.45 | 31.71 | 0.001 | 0.72 | 1.00 |

| Rumination | 251.13 | 1 | 251.13 | 15.12 | 0.001 | 0.75 | 1.00 |

Abbreviations: SS, sum of squares; df, degrees of freedom; MS, mean square; F, F-statistic; η2, eta-squared.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the effects of self-compassion therapy for distress tolerance and rumination in women with MS. The results indicated that the difference between the experimental and control groups in distress tolerance and rumination was significant MS. Thus, self-compassion therapy would have significant effects on distress tolerance enhancement and rumination reduction in women with MS. These findings were consistent with those of previous studies (28, 29).

Self-compassion therapy equips individuals with tools to manage difficult emotions constructively rather than resorting to avoidance or suppression, which is achieved through various techniques, including mindfulness as cultivating present-moment awareness of thoughts and feelings without judgment. Hence, individuals can observe their emotions objectively without being overwhelmed. The other tool is self-kindness to develop a kind and understanding attitude towards oneself, akin to treating a close friend experiencing hardship (26), and the last tool is common humanity, recognizing that suffering and challenges are a universal human experience, fostering a sense of connection with others (35).

Accordingly, self-compassion therapy can activate the parasympathetic nervous system, often called the "soothing system," which promotes calmness and well-being. Anxiety and stress can activate the sympathetic nervous system, or "threat system," which can be counteracted by this technique (24). Furthermore, self-compassion therapy fosters self-awareness and self-compassion through compassion-focused exercises and practices. Women with MS can learn to view themselves with greater understanding and acceptance. The ability to make balanced decisions empowers women to re-evaluate negative self-perceptions that may arise when confronted with stressors that exacerbate their physical and psychological health (22). Improved self-awareness and the ability to reframe challenging situations can contribute to developing better-coping strategies and adherence to long-term treatment plans.

Sympathy and affection for others are emphasized in self-compassion therapy, which was highlighted during the intervention sessions (35). Forgiveness and sympathy toward others increase the social support network, which, in turn, enhances distress tolerance (29). The re-interpretation of events based on the modified conditions increases liveliness, improving the quality of life and distress tolerance in women with MS during training sessions. Overall, self-compassion appears to be effective in enhancing distress tolerance in women with MS.

Rumination is a maladaptive thinking pattern in emotional disorders. Concern and intolerance of uncertainty may play a protective role in generalized anxiety, as the patient believes they can prevent negative events or outcomes (16). As there is a causal relationship between intolerance of uncertainty, worry, and rumination, engagement in these components would lead to rumination. These individuals believe that rumination could improve their understanding and help solve problems. Furthermore, rumination is a response style that involves repetitive and recurring thoughts concerning the symptoms, causes, and meaning of negative moods through which individuals focus on distress and its causes and effects. These thoughts revolve around a common theme and involuntarily penetrate the consciousness, deviating one’s concentration from one's goals (15). In addition, self-compassion therapy, along with other new therapeutic approaches in third-wave psychology, is intended to diminish pain, suffering, worry, and depression (26). Research has recently shown that self-blame is the major element in self-compassion therapy effectiveness for rumination (24, 27). Therefore, the effectiveness of self-compassion in the rumination improvement of women with MS is confirmed.

5.1. Limitations

All research inherently possesses limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. This study is subject to the following limitations: The current study employed a relatively small sample size. Although the sample size provided sufficient power to detect the hypothesized effects within this study population, the generalizability of the findings to a broader population of women with MS may be limited. The results should be replicated with a larger, more representative sample. The study participants were recruited from the MS Society, and this recruitment strategy may have attracted individuals already actively managing their MS and may be more open to new therapeutic approaches. The findings might not be generalizable to women with MS who are not connected to such support networks. Future studies could explore recruitment strategies that reach a more comprehensive range of women with MS. The study focused on women with MS in Ahvaz (Iran). Cultural factors can influence emotional expression and responses to interventions. The applicability of the findings to women with MS from different cultural backgrounds needs further investigation. The control group did not receive any form of intervention (e.g., attention control group). This absence of a control intervention raises the possibility that observed improvements in the self-compassion therapy group could be partially attributable to a placebo effect. Future studies can benefit from including an active control group that receives a credible but non-specific intervention to account for potential placebo effects.

5.2. Conclusions

Self-compassion therapy demonstrates promise in improving distress tolerance and reducing rumination among women with MS. These findings offer valuable clinical implications for therapists, particularly psychotherapists, by informing the development of supportive environments that foster personal growth and mental health in this population. Additionally, the results may have broader relevance for medical and educational institutions such as MS, psychotherapy, and family therapy centers. Based on the observed positive outcomes in alleviating distress and reducing ruminative thoughts in patients with MS, the inclusion of self-compassion therapy within treatment plans for women with MS in psychotherapy settings warrants further consideration.