1. Background

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, which may impact an individual's cognitive and psychosocial functioning (1). It is a prevalent condition, affecting approximately 7.6% of children aged 3 to 12 years and 5.6% of teenagers aged 12 to 18 (2). Diagnosis of this disorder, currently reliant on the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) criteria, is complex and can be challenging due to the subjective nature of symptom reporting and the potential for misdiagnosis. The DSM-5 outlines eighteen symptoms for this disorder, with a minimum of six symptoms in either the inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity domains required for a diagnosis (3). In other words, for adults, at least five symptoms, and for children, at least six symptoms must be present to diagnose ADHD. Symptoms must have an onset before age twelve and be present in at least two different settings, such as at home, school, or during a clinical evaluation. Based on the presenting symptoms, individuals with this disorder are classified into three distinct subtypes: Predominantly inattentive type, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type, and combined type (4).

Children with ADHD are at risk for a variety of impairments, including academic difficulties, behavioral disturbances, and an increased risk of comorbid disorders. Perhaps the most prominent comorbid disorder is oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), which affects approximately half of these children. Anxiety disorders follow, affecting about a quarter of children with ADHD (5). Anxiety disorders exhibit significant comorbidity with hyperactivity in children, with over 25% of children with hyperactivity meeting diagnostic criteria for at least one anxiety disorder (6).

Social anxiety disorder in children with ADHD is a condition where their anxiety is heightened in specific social situations (7). This can negatively impact a child's relationships with others as they grapple with concerns about making friends, meeting new people, and being in new social environments. Children with social anxiety may exhibit various symptoms, including fear of being negatively evaluated, avoidance of social situations, difficulty initiating conversations, excessive self-consciousness, and physical symptoms like blushing or sweating in social settings. These symptoms can significantly impair a child's social functioning and overall well-being (8).

Furthermore, children with ADHD exhibit significant deficits in acquiring and utilizing social skills, and their self-esteem is typically lower compared to their typically developing peers (9). These children often encounter difficulties in peer interactions, academic performance, and social acceptance, factors that can negatively impact their self-concept and self-esteem (10). Self-esteem refers to an individual's positive or negative self-evaluation and feelings about oneself (11). Self-esteem is a crucial aspect of overall functioning and is linked to various domains, including psychological, social, and academic well-being (12).

Current evidence-based interventions for children with ADHD include behavioral therapy (BT), pharmacotherapy, and a combination of both. Many other interventions are often used alongside or instead of evidence-based treatments for ADHD (13), such as child-parent relationship therapy (CPRT).

Child-parent relationship therapy is a therapeutic approach grounded in the theory that a strong, secure, and positive parent-child relationship is essential for a child's emotional and behavioral well-being. By focusing on enhancing the parent-child bond and improving parenting skills, CPRT aims to create a supportive and nurturing environment that promotes the child's social, emotional, and cognitive development.

Given the need for effective therapeutic interventions to mitigate the effects of maladaptive parent-child interactions, parents, particularly mothers, play a pivotal role (14). In this approach, parents are not only utilized as therapeutic substitutes but also empowered, reducing feelings of guilt and despair. This often leads to greater therapeutic collaboration and engagement compared to when the therapist works solely with the child (15). Since parents share a strong emotional bond with their child, a connection that therapists often lack, this natural and inherent bond between parent and child is likely the key to the high efficacy and enduring results of parent-child-centered interventions (16).

The focus of CPRT is on improving the parent-child relationship and the child's inner self. Primary goals for parents include: Understanding and accepting the child's emotional world, developing a realistic and patient perspective towards themselves and the child, increasing parental self-awareness in relation to the child, altering parental perceptions of the child's behavior, learning child-centered play therapy skills and how to create a non-judgmental, accepting, and mutually understanding environment for the child, and ultimately helping parents enjoy their parenting role (17, 18).

Child-parent relationship therapy has demonstrated efficacy in addressing various emotional and behavioral challenges in children. Researchers have found that CPRT has the potential to reduce symptoms of emotional problems, as well as negative cognitions and attitudes in children and adolescents. This therapy has been shown to decrease separation anxiety and social anxiety in children (19); improve the functioning of children with ADHD (20); enhance the quality of parent-child interactions and reduce aggression in preschoolers (21); and decrease behavioral problems in children with ADHD (22).

Children with ADHD commonly struggle with significant behavioral and emotional regulation difficulties, which can impair social interactions at home and school. Some of these issues include social problems, aggression, and rule-breaking behavior. If left untreated in childhood, these problems can lead to adult difficulties such as substance abuse, workplace defiance, shorter job tenure, and increased antisocial behaviors. This disorder is not exclusive to childhood and can persist into adulthood. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is a highly prevalent neurodevelopmental disorder in childhood, and if left unaddressed, it can lead to more severe problems in adulthood. While previous research has explored various interventions for ADHD, a research gap exists in understanding the efficacy of CPRT in addressing specific psychosocial outcomes like social anxiety and self-esteem.

2. Objectives

To fill this gap, the present study aimed to investigate the efficacy of CPRT on social anxiety and self-esteem in children with ADHD.

3. Methods

3.1. Design and Participants

The present study employed a quasi-experimental pre-test-post-test control group design. The population consisted of all 7 - 12-year-old boys and girls diagnosed with ADHD in Amol city in 2023 who had sought counseling services. The research sample was selected after completing a questionnaire and meeting the inclusion criteria, with parental consent obtained for participation. Given the nature of the study, a convenience sample of 44 participants who met the inclusion criteria was selected. To ensure group equivalence, participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental group (n = 22) or the control group (n = 22) using a simple random sampling method. A priori power analysis with G*Power determined a sample size of 22 per group (effect size = 0.90, alpha = 0.05, power = 0.90). Inclusion criteria included scores below the mean on the Self-Esteem Questionnaire, scores above the mean on the Social Anxiety Questionnaire, no prior participation in psychotherapy sessions, and no use of ritalin medication. Exclusion criteria included a history of psychotropic medication use, refusal to continue participation, and more than two absences from the intervention program. Before the study commenced, ethical approval was secured from the appropriate ethics committee. Informed consent was acquired from all participants as well as their parents or legal guardians. Participants were made aware of the study's objectives, procedures, potential risks and benefits, and their right to withdraw at any point. The confidentiality of all data was preserved throughout the research process.

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale for Children and Adolescents

Developed by Masia-Warner et al. (23), Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale for Children and Adolescents (LSAS-CA) is a 48-item self-report measure rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. Designed for children and adolescents aged 7 - 18, this scale assesses a broad range of social interactions and situations that induce fear and avoidance. It also aids in the diagnosis and treatment of social anxiety disorder. A cutoff score of 60 was used, with scores above 60 indicating the presence of social anxiety. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha was employed to assess the internal consistency of the Social Anxiety Questionnaire, yielding a coefficient of 0.84.

3.2.2. Children's Self-Esteem Questionnaire

The Children's Self-Esteem Questionnaire, consisting of 20 items, was employed to assess children's self-esteem (24). This checklist uses a 4-point Likert scale (very much, much, little, very little), with scores of 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. The minimum possible score is 20, and the maximum is 80, with higher scores indicating higher self-esteem. The questionnaire is designed to measure overall, social, academic, family, and physical self-esteem. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha was used to assess the internal consistency of the self-esteem questionnaire, yielding a coefficient of 0.87.

3.3. Intervention

In this study, CPRT (25) refers to a 10-session protocol conducted twice weekly for 90 minutes per session. A summary of the sessions is presented in Table 1. The CPRT sessions were delivered by experienced therapists with specialized training in child and family therapy. The control group, which did not receive the CPRT intervention, was placed on a waitlist.

| Sessions | Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction of group members and therapist, explanation of the process and group rules, brief overview of CPRT, articulation of goals, essential concepts, and training in reflective listening |

| 2 | Creation of a supportive atmosphere and facilitation of communication among parents, preparation of parents for implementing in-home play sessions by reviewing reflective listening, familiarization of parents with the basic principles of play sessions, the importance of creating a structure for play sessions, selection of toys, and appropriate time and place for play sessions with children, role-playing and demonstration of essential play skills |

| 3 | Explanation of the do's and don'ts of play sessions, role-playing the do's and don'ts of play sessions, and providing parents with a checklist of the play session process along with additional guidelines |

| 4 | Teaching the three-step acknowledge the feeling, communicate the limit, and target acceptable alternatives (A-C-T) method for setting limits, explanation of the rationale and importance of setting rules and limits, and role-playing limit-setting skills |

| 5 | Review of parents' reports on play sessions and critique of parent-recorded videos, review of limit-setting skills and practice through role-playing |

| 6 | Creation of a poster outlining the do's and don'ts of play sessions, teaching the skill of giving children choices |

| 7 | Support and encouragement of parents in using learned skills, teaching the skill of providing constructive self-esteem-boosting responses and reflective listening |

| 8 | Teaching the skill of offering encouragement versus praise and role-playing related scenarios |

| 9 | Support and encouragement of parents in using learned skills, teaching advanced limit-setting skills and role-playing related scenarios |

| 10 | Review of parents' reports on play sessions and critique of parent-recorded videos, review of the basic principles of CPRT and learned skills, teaching how to generalize skills beyond play sessions |

Abbreviation: CPRT, child-parent relationship therapy.

3.4. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) in SPSS-27 statistical software.

4. Results

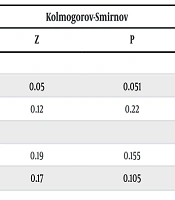

Participants included 44 children (boys and girls) diagnosed with ADHD, aged between 7 and 12 years. The mean age of participants in the CPRT group was 10.46 ± 3.62 years, and 9.68 ± 4.34 years in the control group. The CPRT group comprised 17 (77.27%) boys and 5 (22.73%) girls, while the control group consisted of 15 (68.18%) boys and 7 (31.82%) girls. Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for the variables of social anxiety and self-esteem.

| Variables and Phases | CPRT Group | Control Group | Kolmogorov-Smirnov | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z | P | |||

| Social anxiety | ||||

| Pre-test | 60.27 ± 4.71 | 90.86 ± 5.58 | 0.05 | 0.051 |

| Post-test | 49.73 ± 5.57 | 88.41 ± 6.02 | 0.12 | 0.22 |

| Self-esteem | ||||

| Pre-test | 35.32 ± 3.60 | 35.05 ± 2.27 | 0.19 | 0.155 |

| Post-test | 63.59 ± 5.34 | 36.00 ± 3.10 | 0.17 | 0.105 |

Abbreviation: CPRT, child-parent relationship therapy.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated.

As indicated in Table 2, mean social anxiety and self-esteem scores among children diagnosed with ADHD exhibited significant changes within the CPRT group from pre-test to post-test evaluations. Conversely, no substantial alterations were detected in the control group. To identify significant inter-group differences, a univariate ANCOVA was implemented. Prior to ANCOVA execution, underlying assumptions were verified. Initial assessment of Table 2's Kolmogorov-Smirnov test results confirmed the absence of influential outliers within the study variables, thereby fulfilling the normality assumption requisite for ANCOVA. Subsequently, Levene's test was utilized to evaluate homogeneity of variances, ensuring equivalent variance between the CPRT and control groups. Results for social anxiety (F = 0.29, P = 0.591) and self-esteem (F = 2.68, P = 0.336) supported the assumption of homogeneity. Furthermore, the homogeneity of regression slopes assumption was examined for both social anxiety (F = 0.97, P = 0.389) and self-esteem (F = 1.91, P = 0.162) and found to be tenable. To contrast the CPRT and control groups based on post-test metrics, while controlling for pre-test influences, ANCOVA was conducted to ascertain the efficacy of the CPRT intervention on social anxiety and self-esteem in children with ADHD. Post-test phase outcomes are detailed in Table 3.

| Variables | SS | df | MS | F | P | η2 | Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social anxiety | 16504.34 | 1 | 16504.34 | 495.91 | 0.001 | 0.93 | 1.00 |

| Self-esteem | 8322.91 | 1 | 8322.91 | 433.94 | 0.001 | 0.92 | 1.00 |

Abbreviations: SS, sum of squares; MS, mean square; df, degrees of freedom; F, F-statistic; P, P-value; η2, eta-squared.

As depicted in Table 3, a significant difference was observed between the mean pre-test and post-test scores of social anxiety after controlling for pre-test effects (F = 495.91, P < 0.001, η² = 0.93). This finding indicates that CPRT was effective in improving social anxiety. Similarly, a significant difference was found between the mean pre-test and post-test scores of self-esteem after controlling for pre-test effects (F = 433.94, P < 0.001, η² = 0.92). Consequently, it can be concluded that CPRT was also effective in enhancing self-esteem.

5. Discussion

This research examined the effectiveness of CPRT in mitigating social anxiety and enhancing self-esteem among children diagnosed with ADHD. The primary finding indicated that CPRT exerted a significant positive impact on reducing social anxiety among children with ADHD. This result aligns with the findings of previous studies by Jahanbakhshi and Shabanii (26). To elucidate this finding, social anxiety is a prevalent challenge among children with ADHD, which can negatively impact their quality of life and social functioning. Child-parent relationship therapy has emerged as an effective approach to mitigate this anxiety. By actively engaging parents in their children's treatment, CPRT promotes improved mental health outcomes. The CPRT emphasizes the establishment of positive and supportive parent-child relationships, fostering feelings of security and self-esteem in children with ADHD and consequently reducing social anxiety (21). Moreover, parents are equipped with the necessary skills to teach their children effective social behaviors. Acquiring these skills empowers children to navigate social situations more confidently, thereby preventing the onset of social anxiety (17). Clinicians can consider incorporating CPRT into their treatment plans for children with ADHD, particularly those who exhibit significant social anxiety. By addressing both the child's emotional needs and the parent-child relationship, CPRT offers a comprehensive approach to improving the overall well-being of children with ADHD.

Parents can serve as role models for their children. Positive and constructive parental behaviors in the face of social challenges can teach children how to cope with similar situations, thereby reducing social anxiety (22). The CPRT can bolster children's self-esteem. When children feel supported by their parents, they perceive themselves as capable of overcoming challenges, which can alleviate feelings of anxiety. The CPRT emphasizes the creation of a supportive family environment. Such an environment can foster children's comfort in expressing their emotions and concerns, consequently reducing social anxiety. Parents can also assist children in managing their emotions and stress (26). By teaching stress and emotion management techniques, parents can equip children with the tools to navigate social situations and mitigate anxiety. Effective CPRT necessitates active parental engagement. This involvement can enhance parental responsibility and improve the quality of parent-child interactions, further contributing to reductions in social anxiety.

Furthermore, the findings revealed that CPRT was effective in enhancing self-esteem among children with ADHD. This result aligns with the findings of a previous study conducted by Azizi et al. (21). Self-esteem is a pivotal factor in children's psychosocial development and can be adversely affected by the behavioral and cognitive challenges associated with ADHD. Low self-esteem can lead to difficulties in social interactions, academic performance, and overall well-being. The clinical implications of this study suggest that CPRT can be an effective intervention to address self-esteem issues in children with ADHD. The CPRT can play a significant role in boosting self-esteem in these children. The CPRT is grounded in fostering feelings of security and trust. When children feel safe, they are more likely to express themselves authentically and gradually develop higher levels of self-esteem. Parents can cultivate feelings of self-worth in their children through emotional support (20). This support helps children feel valued and affirmed as individuals, especially during challenging times. The CPRT facilitates the provision of positive feedback, which can help children recognize their strengths and accomplishments. By addressing both the child's emotional needs and the parent-child relationship, CPRT offers a comprehensive approach to improving the overall well-being of children with ADHD, including their self-esteem.

Parents who successfully identify and affirm their children's strengths can foster their self-esteem. This therapeutic approach equips parents to teach their children essential social skills. By acquiring these skills, children experience increased feelings of competence and acceptance, thereby enhancing their self-esteem. Parents can empower children to feel more capable of managing daily challenges. This sense of control and efficacy can boost their self-esteem and propel them towards greater achievements (21). The CPRT can provide parents with the tools to help their children cope with criticism and challenges. This ability enables children to maintain a sense of self-worth when faced with adversity. Parents can teach children to learn from their experiences. This approach can mitigate feelings of failure and consequently improve self-esteem. Parents serve as behavioral models for their children. Positive parental behaviors can convey to children the value of effort and perseverance, ultimately bolstering their self-esteem.

5.1. Limitations

Given that this research was conducted with children diagnosed with ADHD in Amol, caution should be exercised when generalizing the findings to other age groups and geographical locations. Additionally, the relatively small sample size and the use of a convenience sampling method may limit the generalizability of the results.

5.2. Conclusions

The findings of this study provide compelling evidence for the efficacy of CPRT in ameliorating social anxiety and enhancing self-esteem among children diagnosed with ADHD. The significant reductions in social anxiety scores observed in the experimental group, compared to the minimal changes in the control group, underscore the effectiveness of CPRT in addressing this core symptom of ADHD. Moreover, the substantial increase in self-esteem scores among the intervention group highlights the therapy's potential to positively impact children's overall psychosocial well-being. These results contribute to the growing body of literature supporting the use of CPRT as a promising intervention for children with ADHD and their families.

Future research may benefit from exploring the long-term effects of CPRT, investigating potential moderators or mediators of treatment outcomes, and examining the generalizability of these findings to different cultural and socioeconomic contexts. Additionally, longitudinal studies can provide valuable insights into the sustained impact of CPRT on children's social, emotional, and behavioral development. Furthermore, future research could explore the potential benefits of combining CPRT with other therapeutic techniques, such as cognitive-BT or mindfulness-based interventions, to enhance treatment outcomes.