1. Background

Migration is a universal phenomenon in the present era, historically linked to factors such as livelihood, culture, and significant life events (1, 2). According to the United Nations' 2020 report, approximately 281 million people, or 3.6% of the global population, lived in a country other than their birthplace (2). People migrate for various reasons, including social, financial, economic, and educational challenges or aspirations for higher levels of personal, economic, cultural, and social development (3). Upon arriving in the destination country, immigrants often face challenges, such as culture, language, social norms, and family and social relationships. These challenges can profoundly impact multiple facets of their lives and socialization processes and may be perceived as a form of grief (4, 5). The motivation for migration, even when voluntary and positive, entails separation from friends and family, loss of valuable possessions, and a physical and emotional distance from one's homeland, often triggering a process of mourning (6).

Children often migrate as part of family units without personal choice and are particularly vulnerable to migration challenges (4). In the host country, they may experience significant lifestyle changes, such as a smaller living space, fewer toys and recreational activities, and losing friendships. The disappearance of familiar socio-cultural markers can create a more complex identity structure, potentially leading to identity conflicts and affecting their psychological well-being. These disruptions contribute to a specific type of grief associated with migration, often called "migration grief" (4, 7).

When migration-related grief in children is left untreated, issues related to acculturation, socialization, and, ultimately, the successful integration of children in the host country may arise, potentially leading to significant economic costs for the host country. To mitigate the adverse effects of migration grief on the mental health, functional abilities, and social cohesion of immigrant children, it is essential to develop accurate tools for assessing migration grief levels and to establish suitable therapeutic interventions (8, 9). Complicated grief therapy (CGT) is a proven method for addressing symptoms of complicated grief and may serve as a foundation for developing interventions tailored to migration grief in children (10).

The prevalence of migration grief among immigrant children clearly impacts their mental health and significantly hinders their adaptation to new environments (3, 5). Depression is one such consequence of migration and was the primary focus of the present study. No similar study has been conducted in Iran, making this research a pioneering effort in the field.

2. Objectives

The primary aim of this study was to assess the effectiveness of the modified complicated grief therapy (MCGT) intervention in treating depression among immigrant children.

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling

This study was applied to employ a quasi-experimental design (pre-test and post-test). Thirty Iranian immigrant children living in Canada were selected through convenience sampling, with 15 children assigned to the intervention group and 15 to the control group. However, at the post-test stage, 5 participants from each group opted not to continue, resulting in 10 participants in both the intervention and control groups. The sample size was determined using Equation (1), where Z = 1.96, P = 0.915, q = 0.085, and d = 0.05.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Sample Selection

3.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

(1) Willingness to participate in the study.

(2) Children aged from 9 to 15.

(3) At least six months and a maximum of 12 months have passed since the person entered the host country.

(4) The individual’s general intelligence falls within the normal range, with no significant developmental disorders like autism.

(5) There is no history of co-existing psychological disorders, such as hyperactivity, or any such conditions that have been effectively managed before the immigration process.

(6) Migration grief symptoms have led to substantial disruptions in daily functioning that cannot be attributed to any other disorder.

(7) The children did not participate in any rehabilitation or psychotherapy programs during the study period.

3.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

(1) Unwillingness to continue participating in the study.

(2) Not completing the questionnaire.

(3) Lack of more than two sessions in the educational intervention program.

3.3. Children's Depression Inventory

The instrument used in the present study was the self-report Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI), a scale designed to assess psychological symptoms of depression in children and adolescents. Originally developed by Kovacs and Beck (1977) to evaluate depression levels among individuals aged 7 to 17, the CDI consists of five subscales: Negative mood, ineffectiveness, negative self-esteem, interpersonal problems, and anhedonia (11, 12). The CDI includes 27 items, each presented as three statements from which children select the one that best reflects their feelings, thoughts, and behaviors over the past two weeks, assessing symptoms such as crying, concentration difficulties in school, and suicidal ideation (12). The items on the CDI are scored to indicate the severity of depressive symptoms: A score of 0 represents the absence of symptoms, a score of 1 indicates moderate symptoms, and a score of 2 represents specific symptoms. The possible scores range from 0 to 54, with higher scores reflecting greater depression severity. Of the 54 items, 27 questions (items 1, 3, 4, 6, 12, 14, 17, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 26, and 27) are scored directly, while the remaining 13 items (items 2, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 15, 16, 18, 21, and 25) are reverse-scored (13, 14). In a study by Deshiri et al., the psychometric properties of the CDI were preliminarily assessed, revealing test-retest reliability and internal consistency values of 0.82 and 0.83, respectively. The CDI shows convergent solid validity, with correlations of 0.79 with the Children’s Depression Scale and 0.87 with the Beck Depression Inventory. Confirmatory factor analysis results have also demonstrated that the five-factor model of the CDI is appropriate for use in Iranian populations (14). Further validating this tool, Taheri et al. reported suitable validity for the CDI in their study (12). Logan et al. found an internal consistency of 0.89 using Cronbach’s alpha, indicating strong reliability (15). Sharifzadeh et al. also reported a Cronbach’s alpha of approximately 0.89 for the CDI, confirming its reliability (13).

3.4. Modified Complicated Grief Therapy

Complicated grief therapy is a relatively new psychotherapy model designed to address symptoms of prolonged and complex grief. Complicated grief therapy is grounded in attachment theory and integrates elements from interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and extended exposure techniques. Additionally, CGT emphasizes personal goals and relationship building. Studies have shown that CGT effectively alleviates complex grief symptoms, with recipients demonstrating quicker and more substantial treatment responses (16). In the present study, CGT (typically conducted over 16 sessions) was adapted into MCGT, which consisted of 12 sessions. To validate MCGT, both formal and content validity assessments were conducted. In the qualitative formal validity stage, expert feedback was applied to reduce session number, simplify content, clarify language for younger participants, and refine grammar and wording. These adjustments aimed to make the intervention more accessible and effective for children. To assess content validity, the educational intervention was reviewed by 15 professors and experts in adolescent psychology using the Content Validity Index (CVI) and Content Validity Ratio (CVR) metrics. Experts’ feedback was gathered to calculate the CVR. First, the intervention goals were presented to the professors, who were then asked to rate each item based on a three-point Likert Scale: "essential," "useful but not essential," or "not essential." The CVR was subsequently calculated according to Equation (2), with a retention criterion of 0.51, as outlined in Lawshe’s table (17).

In this equation, nₑ represents the number of experts who rated the item as essential, while N is the total number of specialists involved in assessing the intervention's validity. Following this validation, the reliability of the intervention was determined using Cronbach's alpha method, yielding a reliability score of 0.81. The MCGT intervention desiwas designed by the researcher and rised a 12-session program implemented with the intervention group. The MCGT’s effectiveness was evaluated based on its alignment with the original CGT framework. When deciding which sessions and techniques to include, the researcher prioritized those suitable for group settings and those that did not require extensive expertise or specialized training.

3.5. Implementation of the Modified Complicated Grief Therapy Intervention

The intervention was scheduled based on an agreement with participants that it would take place at 12:00 noon Tehran time. Before the educational sessions began, demographic information was recmpleted by both the control and interven completed the CDI questionnairetion groups. The link to the CDI questionnaire was shared with participants via WhatsApp. The intervention group participated in the MCGT program over 12 weeks, while the control group received no intervention. Sessions for the intervention group were conducted online. A Google Meet group was set up via mobile phone, and all children in the intervention group joined for their sessions. According to a prior agreement, the sessions were coordinated to start at 4:30 p.m. Tehran time, which corresponds to approximately 6:30 p.m. in Canada. Eemail notifications were sent out half an hour before each sessio to remind the childrenn. The training sessions lasted one hour each. After completing the intervention sessions, both the control and intervention groups completed the CDI questionnaire again. Finally, a post-test was conducted one month later to gather follow-up data, allowing for an assessment of the intervention’s effectiveness over time.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 22. Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) were utilized to summarize the findings. To evaluate the research hypotheses, inferential statistics, including the Independent Samples t-test, Paired samples t-test, and chi-squared test, were employed. All tests were conducted at a significance level of α = 0.05.

4. Results

The CVI results indicated that all components scored above 0.80, demonstrating strong validity. In this study, the CVR scores for the MCGT components ranged from 0.60 to 0.87 in the preliminary stage, and frm 0.60 to 1.00 in both the middle and final stages, reflecting an appropriate level of validity across all stages. Based on these findings, none of the tool components were excluded from the training program, confirming that all essential and significant elements of CGT were retained. However, as per ext recommendations, the number of MCGT intervention sessions was reduced from 16 to 12.

According to Table 1, of the children participating in the study, 11 (55%) were girls and 9 (45%) were boys. In the intervention group, girls comprised 60% (n = 6), while the number of girls and boys in the control group was equal. Additionally, 60% of the participating children’s families reported a moderate economic status. The analysis indicated no significant statistical differences between the control and intervention groups regarding gender (P = 0.653) and economic status (P = 0.766). The average age of the children was 11.7 ± 1.79 years, with fathers averaging 41.35 ± 4.96 years and mothers 37.35 ± 5.04 years. Furthermore, there were no statistically significant differences between the control and intervention groups in terms of children's age (P = 0.639), fathers' age (P = 0.371), or mothers' age (P = 0.588). Additional demographic characteristics of the study participants are detailed in Table 1.

| Demographic Variables Andiheirs Dimensions | Study Groups | Total | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | |||

| Gender | 0.653 | |||

| Male | 5 (50) | 4 (40) | 9 (45) | |

| Female | 5 (50) | 6 (60) | 11 (55) | |

| Economic situation | 0.766 | |||

| Good | 3 (30) | 2 (20) | 5 (25) | |

| Moderate | 6 (60) | 6 (60) | 12 (60) | |

| Poor | 1 (10) | 2 (20) | 3 (15) | |

| Child' age | 11.5 ± 2.06 | 11.9 ± 1.66 | 11.7 ± 1.79 | 0.639 |

| Father' age | 40.30 ± 5.83 | 42.4 ± 4.27 | 41.35 ± 4.96 | 0.371 |

| Mother's age | 36.70 ± 5.18 | 38.00 ± 5.35 | 37.35 ± 5.04 | 0.588 |

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

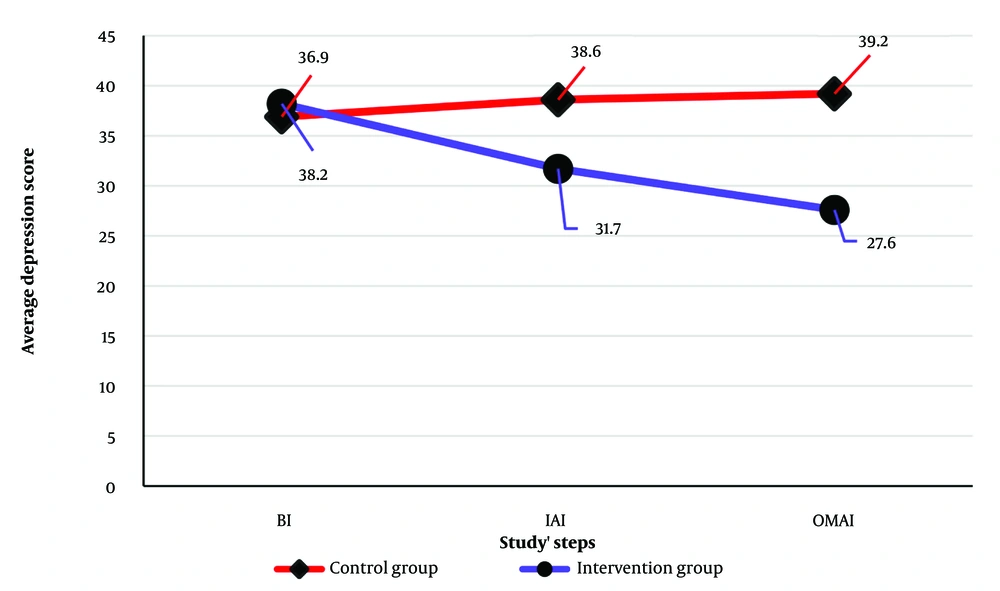

The impact of the MCGT intervention on the average depression scores of children in the control and intervention groups is presented in Table 2. Paired samples t-test analysis indicated no statistically significant difference in average depression scores between the control and intervention groups before the intervention (P = 0.561). However, a statistically significant difference emerged between the groups immediately after the intervention (P = 0.003) and one-month post-intervention (P < 0.001). Specifically, the average depression score in the intervention group decreased by 6.5 points immediately after the intervention and by 10.6 points one month post-intervention compared to the control group. In contrast, depression scores in the control group showed an increasing trend. Repeated measures (RM) analysis further indicated that the trend in depression scores over time (pre-intervention, immediately post-intervention, and one -onth post-intervention) was not significant in the control group (P = 0.307), but was significant in the intervention group (P < 0.001). Figure 1 illustrates the trends in average depression scores across the study period for both groups.

| Main Variable and Different Phases of Study | Control Group | Intervention Group | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | |||

| Before the intervention | 36.90 ± 5.68 | 38.20 ± 3.99 | 0.561 |

| Immediately after the intervention | 38.60 ± 5.16 | 31.70 ± 4.65 | 0.003 |

| One month after the intervention | 39.20 ± 5.39 | 27.60 ± 3.37 | < 0.001 |

| Repeated measure analysis | 0.307 | < 0.001 | - |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

5. Discussion

Many clinicians face challenges in identifying grieving individuals who require treatment and in determining which interventions are most effective for grief-related mental health issues (18, 19). Traditionally, facilitating grief recovery has been a primary focus of psychotherapy (16). To alleviate grief, various therapeutic techniques are often recommended, including pharmacotherapy, supportive therapy, client-centered therapy, existential therapy, cognitive therapy, CBT, interpersonal behavior therapy (IBT), IPT, play therapy, logotherapy, expressive writing, teletherapy, and hypnosis. These interventions have been applied to both children and adults in a wide range of contexts, including hospitalized patients, refugees, couples, parents, and individuals grieving the loss of loved ones due to war, natural disasters, accidents, suicide, and violence (16, 18-20). However, relatively few of these interventions specifically target symptoms of complicated grief. Complicated Grief Therapy, a treatment method rooted in IPT and CBT principles (21), is designed to address these complex symptoms, and prior studies have demonstrated its efficacy for both children and adults (22, 23).

The evaluation results of the CVI and CVR for the MCGT intervention indicated that all tool components scored satisfactory. Consequently, none of the components were removed from the educational program. The high CVI and CVR scores suggest that the MCGT intervention successfully incorporated all essential parameters of the CGT intervention. However, experts recommended reducing the number of sessions from 16 to 12 to enhance the effectiveness of the intervention. Another research question addressed whether the designed therapeutic intervention for children’s migration grief would be effective. The results of this study confirmed the effectiveness of the MCGT intervention. Furthermore, the findings regarding the CVI and CVR levels align with those of Ngesa et al., who examined the effectiveness of MCGT for treating complex grief in children without parental support (24).

The results related to the demographic characteristics of participants and their parents showed no statistically significant difference between the control and intervention groups concerning the child's gender, economic status, age, father's age, and mother's age. This finding indicates the homogeneity of the control and intervention groups, suggesting that these factors did not influence the research outcomes.

Several theories on immigration processes help clarify the relationship between immigration and depression, with acculturation theory being particularly significant (6, 8). Acculturation involves the cultural and psychological changes that occur when individuals from different cultural groups interact. This process affects various aspects of behavior, including food, clothing, language, values, and identity (25-27). Adapting to life in a new country can be inherently stressful, a concept known as "acculturative stress," which describes the psychosocial stress immigrants and their children experience in response to immigration-related challenges (28, 29). This stress may be directly tied to acculturation as individuals cope with loss from leaving their cultural backgrounds. Immigrants might also feel uncertain or anxious about how to behave in unfamiliar social settings (30). Furthermore, practical aspects of migration can add stress, as newcomers often face obstacles like lack of housing, employment, social support, and language proficiency upon arrival (31). Cultural stressors like these can lead to negative emotional states, including depression, especially among immigrant children (28), and the results of the present study support this relationship.

The present study found that children's depression levels were initially high before the intervention. However, both immediately after the intervention and at the one-month follow-up, depression levels had significantly decreased compared to pre-intervention levels and the control group. These findings align with Shear and Gribbin Bloom's study, which demonstrated that CGT interventions significantly improve substantially depression and complicated grief symptoms in immigrants (18). Additionally, in a randomized controlled trial, Shear et al. found CGT to be more effective than other psychotherapy methods for treating symptoms of complex grief disorder and associated depression (32). Similarly, Glickman et al. reported that CGT intervention significantly reduced depression levels in the intervention group compared to the control group (33).

Following migration, many children have encountered traumatic events such as starvation, near-death experiences, torture, illness, injury, and the loss or murder of family members and close friends. Reports indicate that stress and depression are prevalent among these individuals (34). Cognitive behavioral therapy is often one of the primary treatment options for addressing stress and depression in these populations. Paunovic and Ost assessed the effectiveness of CBT in treating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression in refugees. In their study, 16 outpatients exhibiting PTSD symptoms underwent treatment over 16 to 20 sessions. The results demonstrated that CBT led to reductions of 53%, 50%, and 57% in PTSD, general anxiety, and depression symptoms, respectively (35). Similarly, the present study found that the MCGT intervention resulted in a 17% reduction in depression immediately after the intervention and a 28% reduction at the one-month follow-up among the participating children. Since the MCGT intervention incorporates elements derived from CBT, the findings of Paunovic and Ost lend further support to the results of the present study (35). Additionally, Lawton and Spencer conducted a systematic review aimed at examining the effects of CBT on PTSD symptoms, depression, and anxiety in refugee children. Their review, which included 16 studies meeting the inclusion criteria, similarly found reductions in PTSD symptoms, anxiety, and depression following the intervention (36). Thus, it appears that the MCGT intervention has contributed to a positive change in the children's attitudes, which in turn has led to a decrease in their depression levels.

5.1. Limitations

There were limitations in the present study as follows:

(1) The studied population included immigrant children in Canada. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to immigrant children in other countries.

(2) The limited number of immigrant children in the present study, along with the small sample size, restricted the ability to examine differences based on country of origin and racial, ethnic, or cultural variations.

(3) The research data were collected at a specific point in time, and no attention has been paid to the changes in the variables.

(4) The use of self-report instruments in the present study may have been associated with biases.

5.2. Conclusions

Based on the results, MCGT as a therapeutic intervention method has suitable validity for use for immigrant children with depression. In addition, the findings confirmed that MCGT is effective and significant for reducing the depression level in immigrant children. Therefore, counselors and psychologists are suggested to use the MCGT intervention method (as a non-drug method) to reduce depression in children.