1. Background

Midwives play an important role in education and counseling during the prenatal, pregnancy, labor, and postpartum periods, and have a significant impact on preventing mortality and complications during this period (1). Today, employment challenges and unemployment are among the most important issues in Iran, and midwives are also faced with this issue (2). More than one million babies are born in Iran every year, but only ten thousand midwives work in the government system and four to five thousand in the private sector. While, considering the number of births in the country, there should be about thirty thousand people in maternity and health centers, there is a huge difference with the standard of midwifery personnel in health and treatment centers in Iran (3).

The number of midwifery graduates in Iran indicates that there should be no shortage of manpower in this field. However, the recruitment of these personnel into the country's healthcare system is facing difficulties. The lack of clarity in the management and planning organization's plan for replacing retired personnel and defining the employment ceiling for midwives is one of the important reasons for the reduction in the quota for midwifery employment in medical universities and medical centers in Iran (4). Furthermore, the threat to the independence of the midwifery profession is another current problem facing the midwifery community in Iran. While, according to the Ministry of Health guidelines, the field of midwifery is defined as completely independent and can perform its duties without the need for a supervisor (3).

One way to address unemployment and promote professional autonomy in midwifery is through entrepreneurship (5, 6). Innovation and entrepreneurship are important skills of midwives, which have long been recognized as factors in the proper functioning of health and medical organizations and play an important role in providing safe, quality, patient-centered, accessible and affordable care (7). Entrepreneurship in midwifery creates self-employment opportunities for midwives and allows them to pursue their personal visions and passions to improve health outcomes using innovative approaches (8).

Midwife entrepreneurs identify need and create a service to meet that need. They are then recognized as business owners who provide midwifery services of a therapeutic, educational, research, administrative, and consulting nature (9). These individuals are characterized by attitudes that transcend existing environmental conditions and are able to step beyond the environment and see situations through other lenses or from other dimensions. In other words, midwife entrepreneurs are innovators who have the primary motivation to change, modernize health systems, and demonstrate leadership (10).

In Iran, there have been limited studies on the evaluation of midwifery entrepreneurship, and accurate statistics on Iranian midwives are not available. However, the results of studies in other healthcare professions show that entrepreneurs in Iran face multiple challenges in developing entrepreneurship (11). Despite the significant percentage of midwives in the Iranian health system, less attention has been paid to education for the development of entrepreneurship in the midwifery profession and the necessary grounds have not been provided for it. Therefore, providing diverse educational programs that lead to increased awareness, motivation, and instilling entrepreneurial behavior among midwives is strongly felt and is recognized as a challenge in the field of midwifery in Iran (3).

2. Objectives

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of entrepreneurship education on self-efficacy beliefs and entrepreneurial intention of midwifery graduates.

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling

In order to determine the sample size of the present study, according to Equation 1, the formula for comparing two means was used, in which α = 0.05 and β = 0.1, and also, based on the results of previous similar studies (12), X1 = 5.99, X2 = 4.18, S1= 1.34, and S2 = 2.03 were considered. The initial sample size for each of the study groups (including the intervention group and the control group) was 34 people. Considering the probability of about 10% of the subjects dropping out during the study, the final sample size was 38 people for each group, resulting in total of 76 people. To determine the sample size, the confidence level was 95% (Z1-α/2 = 1.96) and the power level was 90% (Z1-β = 1.28). In Equation 1, the sample size, mean, and standard deviation are represented by the letters "N", "X", and "S" symbols, respectively. Each of the samples was selected by simple random method using random number table. Finally, the selected samples divided into two intervention and control groups by block randomization.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Specific criteria were used to select the samples for the present study. Parameters including "bachelor's degree or higher" and "no work experience" were considered as inclusion criteria, while "not attending one of the sessions" and "not completing the questionnaire" were considered as exclusion criteria. In addition, individuals who had previously or currently participated in specific entrepreneurship training courses were not included in the present study.

3.3. Data Collection Tools

The data collection tools in this study included a demographic information form (DIF), General Self-efficacy Scale (13), and Entrepreneurial Intention Questionnaire (EIQ) (14).

3.3.1. Demographic Information Form

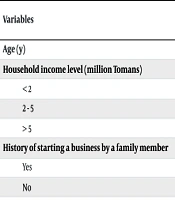

Demographic information form included personal information of study participants such as age, education level, marital status, family history of entrepreneurship, history of starting a private business, and history of participating in entrepreneurship training courses.

3.3.2. General Self-efficacy Scale

The General Self-efficacy Scale (GSES) consists of 17 questions based on a 5-point Likert scale including "strongly disagree" (score 1), "disagree" (score 2), "no opinion" (score 3), "agree" (score 4), and "strongly agree" (score 5). Therefore, the maximum score that an individual can obtain from this scale is 85 and the minimum score is 17. In the GSES, questions 1, 3, 8, 9, 13, and 15 are scored directly, and the remaining questions are scored in reverse (13). The Iranian version of this questionnaire was first translated and validated by Bakhtiari Barati in 1996. In the aforementioned study, to measure the Reliability of GSES, the correlation of scores obtained from this scale with several personality trait measures (including Roter's internal and external locus of control, personal control subscale, Marlo and Keran's social degree scale, and Rosenberg's interpersonal competence scale) was evaluated. The predicted correlation between the self-efficacy scale and the aforementioned personality trait measures was obtained at a moderate level (0.61 and significant at the 0.05 level), which indicated the validity of GSES. Also, the reliability coefficient of GSES was obtained using the Guttman split-half method equal to 0.76 and using Cronbach's alpha coefficient equal to 0.79 (15).

3.3.3. Entrepreneurial Intention Questionnaire

Entrepreneurial Intention Questionnaire has 36 items (questions) and six sections, including the socio-mental norms section (three questions), the general attitude towards entrepreneurship section (fifteen questions), the belief in self-efficacy section (five questions), the attitude towards values and materiality section (five questions), the motivation for progress section (four questions), and the desire for independence section (four questions). The general attitude towards entrepreneurship is measured through three variables, including the attitude towards the advantages and disadvantages of entrepreneurship (nine questions), the social value of entrepreneurship (four questions), and the attitude towards entrepreneurial activity (two questions). The items are rated on a five-point Likert scale including "I strongly disagree" (score 1), "I disagree" (score 2), "I have no opinion" (score 3), "I agree" (score 4), and the option "I strongly agree" (score 5). Questions 1, 2, 8, 9, 12, 20, 27, 28, 31, 32, 35, and 40 are scored in reverse order, and the other questions are scored directly, so the maximum and minimum scores of this questionnaire are 240 and 48, respectively (14). The validity and reliability of the EIQ have been confirmed in a study by Keshavarz. Its face validity has been confirmed by a panel of experts, and the results of the first-order factor analysis of the variables entered in the smart PLS software also indicated the appropriate validity of this tool. In addition, the reliability and internal consistency of the items have been estimated with Cronbach's alpha coefficient between 0.731 and 0.964 (16).

3.4. Research Implementation

This study was an interventional study with a pretest-posttest design and a control group. The independent variable of the present study was "entrepreneurship education" and its dependent variables included "self-efficacy belief" and "entrepreneurial intention". After obtaining the necessary permits to conduct the study, a list of midwifery graduates who were ready to start working was prepared. Then, the researcher met with those who met the inclusion criteria for the study and after explaining how the study would be conducted, the desired samples were randomly selected and written consent was obtained from them.

Next, the DIF was completed by all study participants, and then the GSES and EIQ were provided to both groups and completed by them as a pre-test. Three two-hour training sessions were held on three consecutive days for the intervention group in the form of lectures with questions and answers, while the control group did not receive any training. The intervention sessions were held by the researcher and also by a successful entrepreneurial midwife. It is worth noting that the researcher had previously been trained in the field of entrepreneurship and its concepts by the professor who advised this study. The content of the sessions was selected using reliable entrepreneurship resources and available articles, as well as using the opinions of entrepreneurship experts in this field (Table 1). After completing the training (end of the third session), participants in both study groups were asked to complete the GSES and EIQ questionnaires again as a post-test.

| Session Number | Content of Intervention Sessions |

|---|---|

| First | Concepts of entrepreneurship, midwifery entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial midwives, innovation and creativity, opportunities available in the field of midwifery, sources of opportunity recognition, motivations and personality traits |

| Second | How to start an independent business? obstacles, sources of support, licensing, securing financial and human resources |

| Third | How to manage a business? |

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 23 software. First, the study variables were described using descriptive statistics methods including central and dispersion indices, including mean and standard deviation. Then, for data analysis, the distribution form of quantitative data was checked for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The mean values before and after the intervention (for each study group) were compared using the paired t-test, and the mean of the two groups before or after the intervention was compared using the independent t-test. Comparisons between qualitative variables were examined using the chi-square test (Fisher's exact test). For all analytical tests, significance level of α = 0.05 was considered.

4. Results

In this study, 76 midwifery graduates (38 in each of the experimental and control groups) with an overall mean age of 22.4 ± 12.2 years participated. Most participants (82.9%) reported a monthly income between 2 - 5 million Tomans. Both control and intervention groups had no history of participating in entrepreneurship courses and had not previously started business. Only 9% of participants had family member who had history of starting a business. Based on the results of the relevant tests, there was no statistically significant difference between the two study groups in terms of demographic information (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

| Variables | Study Groups | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | ||

| Age (y) | 22.3 ± 1.2 | 22.5 ± 1.3 | 0.65 |

| Household income level (million Tomans) | 0.08 | ||

| < 2 | 2 (5.3) | 0 | |

| 2 - 5 | 33 (86.8) | 30 (78.9) | |

| > 5 | 3 (7.9) | 8 (21.1) | |

| History of starting a business by a family member | 0.999 | ||

| Yes | 3 (7.9) | 4 (10.5) | |

| No | 35 (92.1) | 34 (89.5) | |

a Values are expressed mean ± SD or No. (%).

The results showed that the difference in the mean score of the variable "entrepreneurial intention" between the experimental and control groups before the intervention was not significant (P = 0.471). After the intervention, the mean of the above-mentioned variable in the intervention group was 243 ± 1, while this value in the control group was 196 ± 1, which was significantly different (P < 0.001) (Table 3).

| Study Groups | Number of Samples | Before Innervation | After Innervation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 38 | 142 ± 4 | 196 ± 1 |

| Intervention | 38 | 143 ± 2 | 243 ± 1 |

| P-value | - | 0.471 | < 0.0001 b |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Significantly: P < 0.05.

The findings of the study, shown in Table 4, indicate that the mean score of the variable "self-efficacy belief" before the educational intervention was not significant between the control and intervention groups (P = 0.558), while the mean of this variable after the intervention was significant (P < 0.001).

| Study Groups | Number of Samples | Before Innervation | After Innervation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 38 | 40.8 ± 0.4 | 84.8 ± 0.4 |

| Intervention | 38 | 45.5 ± 2.7 | 45.8 ± 2.7 |

| P-value | - | 0.558 | < 0.0001 b |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Significantly: P < 0.05.

5. Discussion

Based on the results, it was found that the average score of "self-efficacy belief" before the educational intervention was not significant between the control and intervention groups, while it was significant after the educational intervention. Based on the evaluation made by the researcher, it was found that no study has been conducted on the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education on the self-efficacy of unemployed graduates, and most studies in this field have been conducted on students or employed individuals. In line with the results of the present study, in the study by Jahani et al., which was conducted to evaluate the effect of entrepreneurship education on the self-efficacy belief of nurses, the results of the aforementioned study showed that after the training, significant difference was observed between the two intervention and control groups in terms of self-efficacy belief (7.59 ± 5.4 vs. 5.56 ± 4.6) (P = 0.044). In addition, based on the findings of that study, there was significant difference in the mean self-efficacy belief in the intervention group between the pre- and post-training stages (P = 0.037), while in the control group this difference was not significant (P = 0.837) (17). Also, a study conducted by Sánchez and Gutiérrez on 890 students in economics, social sciences, technical sciences, law, and health in Spain showed that self-efficacy significantly increased after an entrepreneurship education course compared to before (18). In addition, the findings of Mohseni et al. on undergraduate students in industrial management, computer science, and mathematics departments showed that self-efficacy in the intervention group significantly increased after an entrepreneurship education course compared to before the educational programs (19). Although the results of the aforementioned studies are in line with the results of the present study and their findings show that entrepreneurship education is effective in promoting self-efficacy beliefs, despite the differences in the research population and the method of implementation of the aforementioned study with the present study, comparison of the results should be done with caution.

A study by Farsi et al. was conducted to evaluate the effect of opportunity recognition training on nursing students at Zanjan Azad University. The findings of the aforementioned study showed that "self-efficacy" as a main predictor of entrepreneurial intention did not differ significantly after the implementation of the training program compared to before its implementation (P = 0.775), which is inconsistent with the findings of the present study (20). Also, in the study by Osterbeek et al., which was conducted on students of the Faculty of Labor in the Netherlands with the aim of "determining the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education", the results showed that in the post-test, there was no statistically significant difference in self-efficacy between the intervention and control groups, and the average scores in the control group were higher than in the intervention group. Also, the difference in students’ self-efficacy scores in the pre-test and post-test was not significant in either the intervention or control group (21). In explaining the difference in the results of the present study and the study by Farsi et al. (20), various reasons can be mentioned, including the difference in the population under study (midwifery graduates vs. students), the difference in the content of the educational program, and the difference in the method of conducting and collecting data in the aforementioned studies with the present study.

In addition, the findings of the present study showed that the difference in the mean score of the "entrepreneurial intention" variable before the educational intervention between the two experimental and control groups was not significant, while it was significant after the intervention. This finding indicates that entrepreneurship education can be effective in increasing the score of "entrepreneurial intention". As with self-efficacy belief, no study was found on the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial intention of unemployed graduates, and most studies in this field have been conducted on students or employed people. In line with the results of the present study, in the study of Jahani et al., a significant difference was observed between the two groups after the training in terms of the entrepreneurial intention variable (202.47 ± 15.32 vs. 199.58 ± 14.52) in favor of the intervention group (P = 0.047). Also, in the intervention group, there was a significant difference between the mean entrepreneurial intention (P = 0.041) before and after training, while in the control group, this difference was not significant (P = 0.72) (17). Also, in the study by Osterbeek et al., which was conducted on students of the Faculty of Labor in the Netherlands with the aim of "determining the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education", the results showed that in the post-test, there was no statistically significant difference in self-efficacy between the intervention and control groups, and the average scores in the control group were higher than in the intervention group. Also, the difference in students’ self-efficacy scores in the pre-test and post-test was not significant in either the intervention or control group (21). In explaining the difference in the results of the present study and the study by Farsi et al. (20), various reasons can be mentioned, including the difference in the population under study (midwifery graduates Vsstudents), the difference in the content of the educational program, and the difference in the method of conducting and collecting data in the aforementioned studies with the present study. Azizi and Taheri conducted a study to determine the effect of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial intention and characteristics of students participating in entrepreneurship classes, and the results showed that participation in entrepreneurship classes significantly increased students' entrepreneurial intention after the training compared to before the training (12). Arasti et al. evaluated the effect of teaching an optional course on entrepreneurship fundamentals on creating entrepreneurial intention in students from the faculties of Arts, Literature and Humanities at the University of Tehran. The findings of the aforementioned study showed that the entrepreneurship fundamentals training course was effective on students' entrepreneurial intention. Also, the training course in the intervention group significantly increased entrepreneurial intention scores, and after the intervention, a statistically significant difference was observed between the intervention and control groups in this regard (22). Also, in the study by Osterbeek et al., which was conducted on students of the Faculty of Labor in the Netherlands with the aim of "determining the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education", the results showed that in the post-test, there was no statistically significant difference in self-efficacy between the intervention and control groups, and the average scores in the control group were higher than in the intervention group. Also, the difference in students’ self-efficacy scores in the pre-test and post-test was not significant in either the intervention or control group (21). In explaining the difference in the results of the present study and the study by Farsi et al., various reasons can be mentioned, including the difference in the population under study (midwifery graduates Vsstudents), the difference in the content of the educational program, and the difference in the method of conducting and collecting data in the aforementioned studies with the present study (20).

The findings of Nabi et al. showed that entrepreneurship education including business recognition, understanding and creation, entrepreneurial tools and skills, teamwork to present an entrepreneurial program, business management and entrepreneurship for two academic semesters significantly increased the mean entrepreneurial intention in the intervention group students (23). Rankinen and Ryhänen also reported that nursing students’ beliefs and intentions about entrepreneurship increased after 30 hours of entrepreneurship education in the form of lectures, group work, teamwork and online training (24). The findings of Arranz et al. showed that entrepreneurship education had a positive effect on the entrepreneurial intention of undergraduate and graduate students (25). Pruett reported that an entrepreneurship workshop for four years (two sessions per month) significantly increased the entrepreneurial intention of the study participants (26). The findings of Sánchez also showed that an eight-month entrepreneurship education course significantly increased the entrepreneurial intention of students in the intervention group compared to the control group (27). Although the aforementioned studies differ in methodology and research population from the present study, the results of all the aforementioned studies are in line with the findings of the present study, which show that entrepreneurship education can have a significant effect on the entrepreneurial intention of midwifery graduates. In contrast to the results of the present study, Farsi et al. reported that entrepreneurial intention after the implementation of the opportunity recognition training program (26.3 ± 6.2) was not significantly different from that before the implementation of the training program (25.6 ± 6.3) (20).

5.1. Limitations

One of the limitations of the present study was that the psychological characteristics, cultural backgrounds, interests, and motivations of the study participants may have affected the findings from the pre-test and post-test, which were beyond the researcher's control.

5.2. Conclusions

Based on the findings of the present study, it can be concluded that entrepreneurship education has a significant effect on midwives' self-efficacy beliefs and entrepreneurial intentions, so it is essential to hold appropriate training courses for midwifery graduates. In addition, since midwifery students are considered the best asset for promoting an entrepreneurial culture, the findings of the present study can be used to design and enrich the entrepreneurship curriculum and empower students to promote an entrepreneurial culture.