1. Background

Marriage is often anticipated as a significant life event, yet conflict within marital relationships is common (1). A particularly damaging form of conflict is domestic violence, encompassing a pattern of behaviors — including physical aggression, psychological abuse, sexual coercion, economic control, and threats — used by one partner to maintain power and control over the other in an intimate relationship. This issue is a pervasive global problem that transcends cultural, geographic, religious, social, and economic boundaries, disproportionately impacting women (2). Despite its prevalence, domestic violence often goes unreported, sometimes normalized or justified by cultural norms (3). The persistent threat of violence poses a severe risk to family stability and inflicts significant emotional distress on women, including fear, pain, humiliation, and anger (4). Therefore, understanding the psychological factors influenced by domestic violence is crucial for developing effective support.

Among the significant psychological impacts is rumination, a cognitive process involving repetitive, passive focus on negative emotions and the details and meanings of past distressing events, such as experiences of abuse (5). For women experiencing domestic violence, the trauma, fear, and sense of powerlessness can trigger and intensify rumination as they try to make sense of the violence or dwell on the negative feelings associated with it (6). This persistent negative thinking is not merely distressing; it disrupts essential cognitive functions, impairing emotional regulation and problem-solving abilities (7). Consequently, rumination can worsen anxiety and depressive symptoms, foster feelings of learned helplessness, hinder psychological recovery, and make it difficult to cultivate hope for the future (8). It can also make life’s challenges seem less manageable, increasing vulnerability to further psychological distress.

Complementary to the issue of rumination is the concept of sense of coherence (SOC), which reflects a person’s enduring confidence that life is comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful. A strong SOC acts as a buffer against stress and promotes adaptive coping (9, 10). However, the chronic insecurity, unpredictability, and betrayal inherent in domestic violence can severely erode a woman’s SOC (11). The experience often shatters the belief that the world is orderly and predictable (comprehensibility), undermines the confidence in one’s internal and external resources (like coping skills or social support) to meet life’s demands (manageability), and damages the perception that life has purpose and is worth investing energy in (meaningfulness) (12). When comprehensibility is low, the world feels chaotic; when manageability is low, one feels helpless; and when meaningfulness is low, motivation wanes, making challenges seem like burdens rather than tasks worth tackling (13). This erosion of SOC compromises resilience and the ability to navigate life effectively after experiencing violence (12). A weakened SOC can also impede the formation of trusting relationships, potentially leading to social isolation (14).

Given that heightened rumination and diminished SOC are significant psychological burdens for women experiencing domestic violence, interventions targeting these specific issues are vital (15, 16). Addressing rumination can help break cycles of negative thinking and emotional distress, while strengthening SOC can rebuild a woman’s fundamental sense of security, capability, and purpose, fostering resilience. Positive psychotherapy emerges as a relevant and promising therapeutic approach in this context (17). Unlike traditional models that may focus primarily on deficits, positive psychotherapy emphasizes identifying and cultivating individual strengths, positive emotions, and a sense of meaning (18). This focus is particularly pertinent for survivors of domestic violence. By guiding women to recognize their strengths, practice gratitude, savor positive experiences, and reconstruct a sense of meaning in their lives, positive psychotherapy aims directly at counteracting rumination and rebuilding SOC (19, 20). Techniques fostering optimism and cognitive flexibility can help shift focus away from repetitive negative thoughts (21, 22). Furthermore, by emphasizing personal strengths and incorporating mindfulness, positive psychotherapy can enhance a woman’s perceived control over her thoughts and emotions, increase her capacity to manage stressors (bolstering manageability), and help her re-engage with life in a way that feels meaningful, thus directly supporting the recovery of her SOC (23-25). Therefore, evaluating the effectiveness of positive psychotherapy in reducing rumination and enhancing SOC offers a valuable avenue for improving the psychological well-being of women affected by domestic violence.

2. Objectives

Consequently, in consideration of the aforementioned theoretical and empirical considerations, the present study sought to investigate the effectiveness of positive psychotherapy on rumination and SOC among women experiencing domestic violence who were accessing services at counseling centers.

3. Methods

This study employed a quasi-experimental pretest-posttest control group design. The target population consisted of women experiencing domestic violence who sought services at family counseling centers in Ahvaz, Iran, during 2024. Ethical approval for the study protocol was obtained from the relevant institutional ethics committee prior to participant recruitment. All potential participants received comprehensive information regarding the study’s purpose, procedures, expected duration, potential risks and benefits, and the voluntary nature of their involvement. They were explicitly informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any point without penalty and assured that all personal data would be kept confidential and anonymized for reporting. Written informed consent was secured from each woman before her inclusion in the study. A convenience sample of 30 women, who reported experiencing domestic violence and met the inclusion criteria, agreed to participate. Exclusion criteria included concurrent enrollment in other psychological interventions or attending fewer than 80% of the scheduled therapy sessions. These 30 participants were then randomly assigned, using a computer-generated random number sequence, into one of two groups: The experimental group (n = 15), which received eight sessions of positive psychotherapy training, or the control group (n = 15), which received no psychological intervention during the study period but was placed on a waitlist. Following the intervention period for the experimental group, both groups completed the post-test assessments. To ensure ethical treatment, upon completion of the study’s data collection phase, the participants in the control group were offered and received the same positive psychotherapy protocol in an intensive format.

3.1. Measurement Tools

The Rumination Response Scale (RRS), developed by Nolen-Hoeksema et al. (26), is a 22-item self-report instrument used to measure response styles to negative affect. Participants rate items on a four-point Likert scale ('never' to 'always') across three subscales: Reflection, brooding, and depression. Aghebati et al. (27) reported high internal consistency for the RRS (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90). In the current investigation, the internal reliability of the RRS was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, yielding a value of 0.81, which indicates good internal consistency for the scale within this study’s sample.

The SOC Questionnaire, created by Antonovsky (28), assesses an individual’s perceived capacity to manage stress through 13 items rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale (potential score range: 13 - 81). Antonovsky (28) reported Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.82 to 0.95 for this scale. A normalization study in Iran by Mohammadzadeh et al. (29) found a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80. For the present study, the reliability analysis yielded a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.85, suggesting good internal consistency for the questionnaire in this sample.

3.2. Intervention Protocol

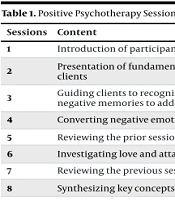

The experimental group received eight 90-minute sessions of positive psychotherapy, structured according to the model proposed by Seligman et al. (30). The content and progression of these sessions are detailed in Table 1.

| Sessions | Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction of participants, building initial rapport, orienting clients to the positive psychology framework, and promoting positive self-identification |

| 2 | Presentation of fundamental positive thinking concepts, identification of positive thinking indicators, and exploration of strengths to foster positive traits in clients |

| 3 | Guiding clients to recognize the impact of positive and negative memories, initiating a gratitude journal, documenting three positive memories, processing three negative memories to address negative emotions, and assigning corresponding homework |

| 4 | Converting negative emotions into positive ones, emphasizing gratitude and forgiveness, and assigning related homework |

| 5 | Reviewing the prior session, concentrating on hope and optimism, and summarizing core concepts |

| 6 | Investigating love and attachment, nurturing positive relationships, analyzing response styles (active-constructive responding), and assigning related homework |

| 7 | Reviewing the previous session, exploring the practice of savoring and deriving pleasure, and assigning related homework |

| 8 | Synthesizing key concepts, promoting a positive environment, highlighting the significance of health in positive psychology, and collecting feedback |

3.3. Statistical Procedures

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 27. The significance level (alpha) for all inferential statistical tests was established at P < 0.05. Prior to the primary analysis, assumptions for the Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) were evaluated. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was applied to determine whether the dependent variables — rumination scores and SOC scores — exhibited a normal distribution within each group (experimental and control). Furthermore, Levene’s test was utilized to assess the homogeneity of variances across groups for each dependent variable. The main statistical method, ANCOVA, was employed to examine the efficacy of the positive psychotherapy intervention.

4. Results

The mean age of participants was comparable between the experimental (M = 33.17, SD = 3.68) and control (M = 32.22, SD = 3.10) groups. Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) for rumination and SOC measured at both pre-test and post-test stages.

| Variables and Stages | Positive Psychotherapy Group | Control Group |

|---|---|---|

| Rumination | ||

| Pre-test | 63.55 ± 9.08 | 61.40 ± 8.34 |

| Post-test | 50.21 ± 7.15 | 60.23 ± 7.20 |

| SOC | ||

| Pre-test | 99.27 ± 15.16 | 97.50 ± 13.78 |

| Post-test | 120.31 ± 17.55 | 99.19 ± 16.53 |

Abbreviation: SOC, sense of coherence.

Table 2 demonstrates a marked change in mean scores for the experimental group across pre- and post-test assessments, whereas the control group exhibited minimal variation. To evaluate the statistical significance of differences between groups, an ANCOVA was conducted. Prior to this analysis, key assumptions were thoroughly assessed. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test verified the absence of significant outliers, confirming adherence to the normality assumption. Levene’s test supported homogeneity of variances for rumination (F = 2.40, P = 0.103) and SOC (F = 1.44, P = 0.280). Additionally, the assumption of homogeneity of regression slopes was satisfied for rumination (F = 2.45, P = 0.196) and SOC (F = 1.97, P = 0.252). Based on these findings, ANCOVA was deemed an appropriate analytical approach.

The impact of positive psychotherapy intervention on post-test rumination and SOC, adjusted for pre-test scores, was examined using ANCOVA. Table 3 presents the findings, which demonstrate a statistically significant intervention effect. Specifically, significant differences were observed between the experimental and control groups in post-test rumination (F = 88.21, P = 0.001, η2 = 0.83) and SOC (F = 43.36, P = 0.001, η2 = 0.72). These large eta-squared (η2) values, often interpreted as effect sizes, indicate that the positive psychotherapy intervention had a very strong impact. For readers unfamiliar with this statistic, these η2 values suggest that approximately 83% of the observed post-intervention difference in rumination and 72% of the difference in SOC between the groups can be attributed to the therapy itself, after accounting for participants’ initial scores. This confirms that the intervention accounted for a substantial proportion of the variance in both outcome variables.

| Variables | SS | df | MS | F | P-Value | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rumination | 1854.13 | 1 | 1854.13 | 88.21 | 0.001 | 0.83 |

| SOC | 2291.09 | 1 | 2291.09 | 43.36 | 0.001 | 0.72 |

Abbreviations: ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; SS, sum of squares; MS, Mean Square; df, degrees of freedom; F, F-statistic; η2, Eta-squared; SOC, sense of coherence.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to determine whether positive psychotherapy effectively reduces rumination and enhances SOC among women exposed to domestic violence accessing family counseling centers in Ahvaz. The findings strongly support the efficacy of this intervention, demonstrating significant reductions in rumination and significant improvements in SOC within this vulnerable population.

The substantial decrease observed in rumination following the positive psychotherapy intervention aligns with previous research conducted in similar contexts (25, 31). While consistent with these specific studies, comparing these findings with a broader range of international research on therapeutic interventions targeting rumination in diverse trauma survivors could provide richer context. The effectiveness of positive psychotherapy in reducing rumination likely stems from several mechanisms of change. Rumination, characterized by repetitive negative thoughts about past experiences and perceived helplessness (20), is common among domestic violence survivors due to chronic fear and injustice. Positive psychotherapy directly counters this by shifting cognitive focus. Techniques such as gratitude exercises, recalling positive experiences, and identifying personal strengths actively compete for cognitive resources, interrupting the ruminative cycle. Furthermore, by fostering hope, optimism, and perceived control, PPT helps challenge the feelings of helplessness often associated with rumination, promoting a more agentic and future-oriented perspective rather than a passive focus on past negative events (25, 31). Identifying and utilizing strengths can enhance self-efficacy, directly counteracting the diminished sense of personal control that fuels rumination.

Similarly, the study confirmed positive psychotherapy’s efficacy in bolstering SOC, consistent with prior findings (22). Again, broader comparison with studies on SOC enhancement across different therapeutic modalities and populations would be valuable. The observed improvement can be attributed to how PPT techniques address the core components of SOC. The emphasis on finding meaning and purpose, even amidst adversity [a key element of positive meaning therapy mentioned by Homayoun Rad et al. (31)], directly strengthens the meaningfulness component. By focusing on identifying and utilizing personal strengths and resources (internal and external), PPT enhances perceived manageability – the belief that one has the resources to cope with stressors (18). Techniques promoting positive reframing, hope, and acceptance may contribute to comprehensibility by helping individuals integrate difficult experiences into a life narrative that, while painful, makes cognitive sense and allows for growth (30). The structured, positive strategies taught in PPT equip women not just to manage negative experiences but to actively build self-confidence, validate their own experiences, and improve various life domains, collectively fostering a stronger, more balanced SOC (18, 24).

It is also important to consider the potential influence of Iranian cultural factors on the intervention’s effectiveness, although this study did not directly measure these effects. Cultural norms regarding family, resilience, and help-seeking could interact with both the experience of domestic violence and the reception of positive psychotherapy. For instance, strong family or community ties, if supportive, could potentially amplify the benefits of interventions focusing on positive relationships and meaning. Conversely, cultural stigma surrounding domestic violence and mental health issues (alluded to in the limitations) might create barriers to disclosure or engagement. Values emphasizing endurance or particular frameworks for finding meaning might shape how participants connect with specific PPT exercises like gratitude or hope cultivation. Future research could benefit from explicitly exploring these cultural nuances to better tailor interventions.

5.1. Conclusions

This study provides robust evidence supporting the efficacy of positive psychotherapy for women experiencing domestic violence, demonstrating significant reductions in rumination and enhancements in SOC. These findings bolster the growing body of literature advocating for the integration of positive psychology principles into trauma-informed care, highlighting the therapeutic potential of strength-based approaches in addressing the psychological sequelae of abuse. For clinicians, the results offer actionable insights, encouraging the incorporation of techniques such as leveraging character strengths, fostering gratitude through journaling, facilitating the savoring of positive memories, and promoting meaning-making activities. Such strategies can complement trauma processing by cultivating positive emotions, resilience, and hope, with tailored application based on clients’ rumination levels, SOC, cultural backgrounds, and readiness. The findings also have broader implications for clinical practice and service design, suggesting that integrating positive psychotherapy components into domestic violence support programs could enhance empowerment and complement deficit-focused approaches. However, further research is imperative to assess the long-term durability of these effects through extended follow-up studies, elucidate specific mechanisms of change, and compare positive psychotherapy’s efficacy against or alongside other trauma interventions. Additionally, investigating its applicability across diverse populations, including varied genders, cultural contexts, and violence severities, while developing culturally sensitive adaptations, will strengthen its utility and generalizability.

5.2. Limitations

This study is subject to several limitations that merit attention. The focus on women experiencing domestic violence referred to family counseling centers in Ahvaz limits the generalizability of findings to other populations, such as men or individuals not seeking counseling, and to diverse geographical or cultural contexts. The absence of follow-up assessments precludes evaluation of the long-term efficacy of positive psychotherapy, necessitating future studies with longitudinal designs. The sensitive nature of domestic violence may have introduced response bias, potentially affecting participants’ candor or cooperation. Additionally, heterogeneity in participants’ education, cultural backgrounds, and violence experiences complicates broad generalizations. Individual differences in personality, coping mechanisms, and intervention responsiveness suggest variable treatment benefits. Lastly, the use of a waitlist control group raises the possibility that observed improvements may partly reflect placebo or non-specific therapeutic effects, such as therapist attention, group support dynamics, or positive expectations, rather than the unique components of positive psychotherapy.