1. Background

Marital quality of life, defined as the subjective satisfaction, adjustment, and relational harmony experienced by spouses within their marriage, is a pivotal determinant of overall well-being, particularly among university students navigating early marital challenges (1, 2). This multifaceted construct encompasses emotional satisfaction, communication quality, relationship stability, and sexual functioning (3). Married students face unique stressors, such as balancing academic workloads, financial constraints, and evolving familial roles, which can strain marital bonds (4). These stressors may disrupt emotional stability and communication, potentially undermining relationship durability (5).

Extensive research has explored the psychological and relational factors influencing marital quality of life (6, 7). Mindfulness, characterized as intentional, non-judgmental awareness of the present moment (8), has been identified as a significant predictor of marital satisfaction (9, 10). Mindfulness mitigates marital stressors by enhancing emotional regulation, reducing conflict reactivity, and fostering empathetic communication, which are critical for students managing academic and relational demands (11). Similarly, interpersonal forgiveness, defined as a positive shift in response to relational offenses (12), promotes marital quality by reducing negative emotions and strengthening relational resilience (13, 14). Studies, such as those by Kavehfarsani et al. (10) and Eftekhari Moghaddam et al. (15), indicate that forgiveness enhances marital quality through improved empathy and conflict resolution. Within the Iranian cultural context, where familial unity is highly valued, forgiveness serves as a strategic mechanism to maintain relational stability, particularly for female students balancing cultural expectations and academic pressures (15). Theoretical frameworks, such as emotion regulation theory and dyadic coping models, underpin the roles of mindfulness and forgiveness in fostering adaptive marital dynamics (5, 16). Notably, gender differences may influence these effects, with women potentially benefiting more from forgiveness due to cultural expectations of nurturing roles, though research on male students remains limited (15).

Despite these insights, gaps remain in the literature. Previous studies, such as those by Afzood et al. (9) and Kavehfarsani et al. (10), have primarily examined mindfulness and forgiveness independently, with limited focus on their combined predictive effects on marital quality among university students. Moreover, few studies have targeted married female students in the Iranian context, where cultural and academic stressors uniquely intersect (15). This study addresses these gaps by investigating the synergistic predictive capacity of mindfulness and interpersonal forgiveness on marital quality of life among married female university students, offering novel insights into tailored interventions for this demographic.

2. Objectives

Consequently, the present study aimed to elucidate how mindfulness and interpersonal forgiveness, grounded in emotion regulation and dyadic coping frameworks, predict marital quality of life in this population, contributing to the development of targeted psychological interventions.

3. Methods

3.1. Design and Participants

The present study adopted a descriptive-correlational research design. The target population for this study encompassed all married female students attending Islamic Azad University of Shiraz during the 2024 academic year. Employing convenience sampling, five faculties were randomly selected from the university’s academic units, and within each faculty, five classes were chosen based on accessibility and instructor permission. Data collection occurred from March to June 2024. A total of 280 research questionnaires were administered to married female students within these designated classes. Following the removal of incomplete or spoiled questionnaires, 259 individuals provided complete responses and were included in the final analysis. A power analysis, assuming a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15), α = 0.05, and power = 0.80, indicated a minimum sample size of 250, justifying the inclusion of 259 participants. Inclusion criteria mandated that participants be currently enrolled married female students at the specified university, whereas exclusion criteria included incomplete questionnaire data, unmarried status, or non-enrollment at the university during the data collection period.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale

Marital quality was assessed using the 14-item Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale (RDAS) (17). This instrument evaluates three facets of dyadic adjustment: Consensus (items 1 - 6), satisfaction (items 7 - 10), and cohesion (items 11 - 14). Responses for items 1 through 10 and items 12 through 14 are captured on a 6-point Likert-type scale (0 - 5), while item 11 utilizes a 5-point scale (0 - 4). Composite scores range from 0 to 69, with higher scores indicating greater marital quality (18). The RDAS has demonstrated strong internal reliability in prior research, with a reported Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85 (19). In this study, the RDAS showed comparable internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84, and its validity was supported by its established use in diverse populations, including Persian-speaking samples (19).

3.2.2. Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire

Mindfulness was evaluated using the 15-item Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) (20). This self-report instrument measures present-moment awareness and non-judgmental acceptance, with responses on a 6-point Likert scale (1 - 6) and total scores ranging from 15 to 90; higher scores reflect greater mindfulness. Prior research has demonstrated strong internal consistency for the FFMQ, with a reported Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86 (18). In the present study, the FFMQ exhibited robust internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88, and its validity was confirmed through prior psychometric evaluations in non-clinical Iranian samples (18).

3.2.3. Interpersonal Forgiveness Measurement Questionnaire

Interpersonal forgiveness was assessed using the 25-item Interpersonal Forgiveness Measurement Questionnaire (IFMQ) (21). This tool measures forgiveness across three dimensions — reconnection and revenge control, resentment control, and realistic understanding — with responses on a 4-point Likert scale (1 - 4) and total scores ranging from 25 to 100; higher scores indicate greater forgiveness. In the present study, the IFMQ demonstrated strong internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85, and its validity was supported by its development and validation in Iranian populations (21).

3.3. Data Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using the statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS), version 26.0. Descriptive statistics, specifically means and standard deviations, were calculated to summarize the sample characteristics and variable distributions. Inferential statistical analyses involved the Pearson product-moment correlation test to examine the linear relationships between marital quality of life, mindfulness, and interpersonal forgiveness, and stepwise multiple regression analysis to evaluate the predictive capacity of mindfulness and interpersonal forgiveness on marital quality of life. All statistical tests were conducted with a significance level of P < 0.01.

4. Results

The demographic characteristics of the sample revealed that 21 participants (8.1%) were undergraduates, 150 (57.9%) were pursuing master’s degrees, and 88 (34.0%) were doctoral candidates. In terms of marital duration, 39 participants (15.1%) had been married for less than one year, 90 (34.7%) for one to five years, and 130 (50.2%) for five to ten years. The age distribution was as follows: Twenty-nine individuals (11.2%) were aged 20 - 25 years, 76 (29.3%) were 25 - 30 years, 83 (32.0%) were 30 - 35 years, 31 (12.0%) were 35 - 40 years, and 40 (15.4%) were 40 - 45 years.

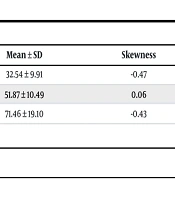

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics for marital quality of life, mindfulness, and interpersonal forgiveness. Marital quality of life had a mean of 32.54 ± 9.91, mindfulness a mean of 51.87 ± 10.49, and interpersonal forgiveness a mean of 71.46 ± 19.10. Skewness values near zero for all variables indicated approximately symmetrical distributions, with interpersonal forgiveness showing a slight negative skew (-1.33), suggesting a modest concentration of higher scores. Kurtosis values near zero indicated roughly mesokurtic distributions, with marital quality of life and interpersonal forgiveness slightly platykurtic (flatter) and mindfulness slightly leptokurtic (more peaked). These distributions suggest that the data are suitable for parametric analyses, with no extreme deviations from normality.

| Variables | Mean ± SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marital quality of life | 32.54 ± 9.91 | -0.47 | 0.01 |

| Mindfulness | 51.87 ± 10.49 | 0.06 | -0.048 |

| Interpersonal forgiveness | 71.46 ± 19.10 | -0.43 | -1.33 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Table 2 presents the Pearson correlation coefficients for the relationships between marital quality of life and the predictor variables. Mindfulness showed a moderate positive correlation with marital quality of life (r = 0.39, P = 0.001), and interpersonal forgiveness exhibited a stronger positive correlation (r = 0.60, P = 0.001). These results indicate that higher levels of both predictors are associated with greater marital well-being.

| Variables | Marital Quality of Life | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Mindfulness | -0.39 | 0.001 |

| Interpersonal forgiveness | 0.60 | 0.001 |

A stepwise regression analysis (Table 3) examined the predictive roles of interpersonal forgiveness and mindfulness on marital quality of life. Assumptions of linearity, independence, homoscedasticity, and normality were assessed and met, with no significant multicollinearity (VIF < 2). In model 1, interpersonal forgiveness alone explained 36% of the variance (R2 = 0.36, F = 145.34, P = 0.001), with a significant positive effect (β = 0.60). In model 2, adding mindfulness increased the explained variance to 42% (R2 = 0.42, F = 93.85, P = 0.001), a statistically significant improvement (ΔR2 = 0.06, P = 0.001). Interpersonal forgiveness (β = 0.54) remained the stronger predictor, followed by mindfulness (β = 0.24). These findings highlight that both variables significantly predict marital quality of life, with interpersonal forgiveness having a more substantial impact.

| Models | Predictor Variables | F | R | R² | B | SE | β | t | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Interpersonal forgiveness | 145.34 | 0.60 | 0.36 | 0.31 | 0.03 | 0.60 | 12.06 | 0.001 |

| 2 | Interpersonal forgiveness and mindfulness | 93.85 | 0.65 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.54 | 10.89 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: SE, standard error; β, standardized beta coefficient.

5. Discussion

The present investigation aimed to evaluate the predictive roles of mindfulness and interpersonal forgiveness in relation to marital quality of life among a sample of university students. The primary finding of this investigation revealed a statistically significant positive correlation between mindfulness and marital quality of life among married female university students. This observation is consistent with the outcomes reported in studies by Afzood et al. (9), Rajabi et al. (22), and Almutairi and Meiri (23). This result can be elucidated by considering mindfulness as a psychological capacity involving the intentional and non-evaluative focus on present moment experiences. This capacity is linked to improved emotional self-regulation, diminished stress reactivity, and enhanced interpersonal communication. Within the realm of marital relationships, mindfulness may contribute to higher marital quality of life by promoting active engagement in the relationship, mitigating conflicts, and fostering greater empathy (9).

Married female students, facing a confluence of academic, familial, and social demands, are vulnerable to psychological stressors that can adversely affect their marital bonds. In these situations, mindfulness, by facilitating emotional management and refining communication skills, can serve as a protective mechanism and bolster marital quality of life (24). Conversely, marital quality of life, characterized by satisfaction, cohesion, and adjustment in the dyadic relationship, is influenced by both intrapersonal and interpersonal variables. Empirical evidence suggests that individuals exhibiting higher levels of mindfulness are more inclined to accept their partners and engage in constructive conflict resolution (10). These characteristics, in turn, contribute to heightened intimacy, trust, and marital satisfaction. Within the specific context of married female students, who may experience constraints on time and energy available for their relationships, mindfulness can facilitate a better equilibrium between their various responsibilities by increasing awareness of both personal and marital requirements. Accordingly, this hypothesis posits a positive association between elevated mindfulness levels and enhanced marital quality of life within this population. This hypothesis is theoretically underpinned by frameworks such as emotion regulation theories and communication models pertinent to marital dynamics. While previous investigations have supported the positive relationship between mindfulness and marital satisfaction, exploring this association among married female students can refine our understanding of mindfulness’s role in demanding environments. The outcomes of this study may inform the development of mindfulness-based psychological interventions aimed at improving marital quality of life in this demographic group. However, direct comparisons with studies focusing on male students are limited by the scope of this research. Future studies should investigate whether these findings generalize to married male students, as gender-specific stressors and coping mechanisms could influence the role of mindfulness in marital quality.

The second significant outcome of this research demonstrated a statistically significant positive association between interpersonal forgiveness and marital quality of life among married female university students. This finding corroborates the results reported by Eftekhari Moghaddam et al. (15), and Ghazanfari Shabankare et al. (25). A potential explanation for this finding is that interpersonal forgiveness among married female students can improve marital quality of life by alleviating tensions stemming from everyday disagreements. This demographic, facing the dual demands of academic and familial responsibilities, is particularly susceptible to stress and marital conflict. The capacity to forgive a partner’s offenses facilitates the replacement of negative emotions, such as anger and resentment, with mutual understanding and empathy. This affective shift fosters a more tranquil relational climate and promotes more productive communication. When married female students are inclined towards forgiveness, their communication patterns within the relationship tend to improve (25). This enhancement not only leads to more effective conflict resolution but also fosters greater trust and intimacy between partners. In circumstances where academic pressures may limit the time and energy available for the relationship, forgiveness functions as a moderating influence, enhancing the relationship's resilience in the face of challenges and mitigating emotional disengagement (15).

Within the Iranian cultural framework, which places a strong emphasis on the preservation of familial unity, forgiveness acquires heightened importance. Married female students, who are tasked with navigating the demands of academic pursuits alongside familial obligations, can utilize forgiveness as a mechanism to prevent the intensification of interpersonal conflicts. This attribute empowers them to pursue constructive resolutions when confronted with the unavoidable errors inherent in marital life, rather than fostering the accumulation of resentment. Indeed, within this context, forgiveness is not indicative of weakness but rather represents a strategic and judicious approach to sustaining relational stability. The significance of this hypothesis resides in its practical implications for marital counseling and psychoeducation. Should a substantial association between forgiveness and marital quality of life be substantiated within this specific demographic, tailored educational programs can be developed to enhance forgiveness capacities. Such initiatives would equip married students with improved coping mechanisms for the multifaceted challenges they encounter. Furthermore, this research can serve as a foundation for the development of couple therapy interventions that are sensitive to the unique needs of the student population, thereby facilitating the enhancement of their dyadic relationships. These findings align with existing theories of relational well-being, which posit that psychological resources like mindfulness and forgiveness contribute to adaptive coping and positive relationship outcomes. Specifically, the results support the idea that emotional regulation (facilitated by mindfulness) and prosocial responses to transgressions (forgiveness) are crucial for maintaining marital quality, especially in demanding contexts.

5.1. Conclusions

In summary, this study’s findings offer empirical validation for the significant positive associations among mindfulness, interpersonal forgiveness, and marital quality of life within a cohort of married female university students. The statistically significant correlations indicate that elevated levels of mindfulness and a greater propensity for interpersonal forgiveness correlate with improved perceptions of marital well-being in this population. Moreover, the considerable predictive capacity of these two variables, explaining 42% of the variance in marital quality of life, emphasizes their relevance in comprehending relational dynamics among young married adults engaged in higher education. Of particular interest is the relatively stronger predictive effect of interpersonal forgiveness, suggesting that the capacity for reconciliation following relational offenses may be a particularly influential factor in cultivating and sustaining marital satisfaction within this specific demographic. However, it is important to avoid overgeneralizing the predictive power of forgiveness and mindfulness; while they account for a substantial portion of the variance, other factors also contribute significantly to marital quality of life. These results augment the expanding literature underscoring the impact of individual psychological resources on marital outcomes and suggest potential directions for interventions designed to enhance marital quality among university students. For instance, specific mindfulness-based interventions could include structured programs focused on mindful communication, cultivating non-judgmental awareness of marital interactions, and stress reduction techniques tailored to academic pressures. Similarly, interventions targeting interpersonal forgiveness could involve exercises in empathy-building, perspective-taking, and guided forgiveness practices to help students navigate relational hurts effectively.

5.2. Limitations

Several limitations warrant consideration when interpreting the outcomes of this investigation. Primarily, given that the study population comprised married female students at Islamic Azad University of Shiraz, the generalizability of these findings to students and other married individuals residing in different urban areas with distinct cultural values and attributes may be constrained. A further limitation lies in the exclusive focus on married female students, thereby excluding their male counterparts, which necessitates a cautious approach when extrapolating the results to married male students. This study's findings on female students may not directly apply to male students due to potential gender-specific factors in marital dynamics. Moreover, the absence of control over potentially confounding variables constitutes another limitation of the current research. It is conceivable that external factors, such as socioeconomic status, individual life experiences, age, the presence of offspring, and the length of the marital union, may have exerted an influence on the study’s findings. Specifically, marital duration, ranging from less than one year to ten years, could potentially moderate the observed relationships, as the dynamics of newly formed marriages may differ from those of more established unions. Future research should explore marital duration as a potential moderating variable. Another significant limitation is the reliance on self-report measures for all variables. While widely used, self-report instruments can be susceptible to social desirability bias and subjective interpretation, which might influence the accuracy of the data collected.