1. Background

The novel coronavirus, the seventh known virus in the family, was named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) on February 11, 2020, by the World Health Organization (WHO). COVID-19 is also a contagious disease caused by SARS-CoV-2. Most people with COVID-19 develop a mild respiratory illness and recover without the need for special care or treatments. Older people and those with underlying diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, and cancer are more likely to develop COVID-19 (1, 2). The SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted primarily through saliva droplets or nasal secretions during sneezing and coughing (3), so practicing good breathing habits (such as coughing at the elbow) is very important. There is currently no specific vaccine or treatment for COVID-19, but clinical trials are ongoing to discover possible treatments (4).

It was reported that enacting social distance policies at the national level was associated with a significant reduction in the transmission of SARS-CoV-2, reducing the rate of viral transmission, as well as COVID19 infection rates (5). The WHO works closely with experts, governments, and global partners to rapidly expand scientific knowledge about SARS-CoV-2. In addition, with timely recommendations, the organization aims to protect public health and prevent the spread of the virus.

The apparently high risk of COVID-19 infection among oil refinery workers may be due to the lack of awareness, inadequate protective measures, and contact with infected people in the community, hospitals, or treatment environments.

2. Objectives

The aim of the present study was to assess clinical characteristics, management, and in-hospital outcomes of COVID-19 among oil refinery workers in a single referral center.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design, Setting, and Population

This cross-sectional study was conducted in a non-COVID single referral center (Naft Grand Hospital, Ahvaz, Iran) from March to August 2020. This study was approved by the Naft Grand Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB), and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before enrollment.

3.2. Specimen Collection Process

At the Naft Grand Hospital, a COVID-19 specimen collection and molecular detection unit was established, and staff were trained how to collect suitable samples (sufficiently deep swabs) and how to store, pack, and transport them. Trained laboratory personnel collected nasal swabs using standard techniques based on health and safety standard protocols. After collection, the swabs were immediately placed into a sterile transport tube containing the viral transport medium and delivered to the laboratory. The diagnosis of COVID-19 infection (SARS-CoV-2) was confirmed by real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Baseline patient characteristics, treatments, and the clinical course of the disease were expressed as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means with standard deviations for continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test, and Fisher's exact test was used when the data were sparse. Continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis test. All tests were two-tailed, and results with P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data preparation and statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS 22.

4. Results

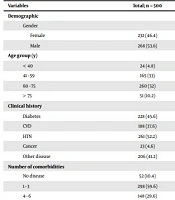

Overall, 500 patients with confirmed COVID-19 were included in this study. In total, 375 (75%) of the patients lived in the metropolitan area, and 125 (25%) lived in urban areas. Men and women constituted 286 (53.6%) and 232 (46.4%) of the patients, respectively. Regarding age, the highest and lowest frequencies were related to the age groups of 60 to 75 and over 75 years with the frequencies of 260 (52%) and 51 (10.2%), respectively. The highest and lowest frequencies of education levels were related to illiteracy and diploma with the frequencies of 80 (16%) and 59 (11.8%), respectively; 255 people (51%) did not determine their education level. Also, 116 people (23.2%) were unemployed; 324 people (64.8%) were employed, and their employment status was unknown in 60 (12%) subjects.

The most common symptoms on admission were dyspnea (56.0%), cough (50.4%), and fever (49.0%). Underlying diseases were reported in 144 patients (28.8%). The most common comorbidities were hypertension (52.2%) and diabetes (45.6%). Moreover, 298 patients (59.6%) had one to three comorbidities; 148 patients (29.6%) had four to six underlying diseases, and two patients (0.4%) suffered from seven and more comorbidities. Finally, 23 people (4.6%) had cancer, and 206 (41.2%) had other diseases.

Regarding COVID-19 treatments, 390 (78.8%) received Kelatra, and 387 (78.02%) received Azithromycin. Overall, PCR result was positive in 377 (75.4%) patients. On the other hand, computed tomography scan (CT-scan) was positive in 413 (82.6%) patients, and the CRP test delivered positive results in 335 patients (67%). Among 55 non-survivors (11% of total), 33 cases (60.0%) were men, and 56.4% of them were in the 65 - 75 years age group. The majority, 34 (61.8%), of deceased patients had hypertension (HTN), and 80% of them were treated with Kelatra. The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients according to their final status (survivor/non-survivor) have been shown in Table 1.

| Variables | Total; n = 500 | Survivor; n = 445 | Non-survivor; n = 55 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||||

| Gender | 0.321 | |||

| Female | 232 (46.4) | 210 (47.2) | 22 (40) | |

| Male | 268 (53.6) | 235 (52.8) | 33 (60) | |

| Age group (y) | < 0.0001 | |||

| < 40 | 24 (4.8) | 23 (5.2) | 1 (1.8) | |

| 41 - 59 | 165 (33) | 156 (35.1) | 9 (16.4) | |

| 60 - 75 | 260 (52) | 229 (51.5) | 31 (56.4) | |

| > 75 | 51 (10.2) | 37 (8.3) | 14 (25.5) | |

| Clinical history | ||||

| Diabetes | 228 (45.6) | 127 (28.5) | 17 (30.9) | 0.753 |

| CVD | 188 (37.6) | 161 (36.2) | 27 (49.1) | 0.076 |

| HTN | 261 (52.2) | 227 (51) | 34 (61.8) | 0.153 |

| Cancer | 23 (4.6) | 17 (3.8) | 6 (10.9) | 0.031 |

| Other disease | 206 (41.2) | 174 (39.1) | 32 (58.2) | 0.009 |

| Number of comorbidities | 0.001 | |||

| No disease | 52 (10.4) | 49 (11) | 3 (5.5) | |

| 1 - 3 | 298 (59.6) | 275 (61.8) | 23 (41.8) | |

| 4 - 6 | 148 (29.6) | 120 (27) | 28 (50.9) | |

| 7 + | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| PCR result | 0.754 | |||

| Positive | 377 (75.4) | 334 (75.1) | 43 (78.2) | |

| Negative | 117 (23.4) | 106 (23.8) | 11 (20) | |

| Unknown | 6 (1.2) | 5 (1.1) | 1 (1.8) | |

| CT result | 0.842 | |||

| Positive | 413 (82.6) | 366 (82.2) | 47 (85.5) | |

| Negative | 25 (5) | 23 (5.2) | 2 (3.6) | |

| Suspicious | 29 (5.8) | 27 (6.1) | 2 (3.6) | |

| Unknown | 33 (6.6) | 29 (6.5) | 4 (7.3) | |

| Effective PCR result | 461 (92.2) | 413 (92.8) | 48 (87.3) | 0.177 |

| Effective CT result | 461 (92.2) | 411 (92.4) | 50 (90.9) | 0.603 |

| Effective clinical diagnosis | 167 (33.4) | 147 (33) | 20 (36.4) | 0.651 |

| Effective laboratory results | 477 (95.4) | 427 (96) | 50 (90.9) | 0.160 |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Fever | 245 (49) | 220 (49.4) | 25 (45.5) | 0.668 |

| Cough | 252 (50.4) | 231 (51.9) | 21 (38.2) | 0.063 |

| Dyspnea | 280 (56) | 247 (55.5) | 33 (60) | 0.567 |

| Myoliagia | 79 (15.8) | 73 (16.4) | 6 (10.9) | 0.334 |

| Anorexia | 57 (11.4) | 53 (11.9) | 4 (7.3) | 0.375 |

| Diarrhea | 30 (6) | 26 (5.8) | 4 (7.3) | 0.559 |

| Headache | 29 (5.8) | 26 (5.8) | 3 (5.5) | > 0.99 |

| Sore Throat | 12 (2.4) | 11 (2.5) | 1 (1.8) | > 0.99 |

| Olfactory dysfunction | 12 (2.4) | 10 (2.2) | 2 (3.6) | 0.631 |

| Nausea | 46 (9.2) | 43 (9.7) | 3 (5.5) | 0.457 |

| Fatigue | 148 (29.6) | 130 (29.2) | 18 (32.7) | 0.639 |

| Other symptoms | 11 (22.2) | 89 (20) | 22 (40) | 0.002 |

| Laboratory results | ||||

| Normal LDH | 118 (23.6) | 115 (48.9) | 3 (13) | 0.001 |

| Lymph | 24.42 ± 12.94 | 25.07 ± 12.74 | 18.90 ± 13.42 | < 0.001 b |

| PMN | 57.46 ± 12.76 | 57.62 ± 12.28 | 56.10 ± 16.24 | 0.523 b |

| Hb | 12.08 ± 1.94 | 12.15 ± 1.93 | 11.51 ± 1.97 | 0.022 b |

| WBC | 7744.54 ± 4438.05 | 7528.69 ± 4287.91 | 9490.91 ± 5229.06 | 0.012 b |

| Platelet | 216.03 ± 81.33 | 214.90 ± 78.45 | 255.18 ± 102.11 | 0.794 b |

| Treatments | ||||

| Kelatra | 390 (78.8) | 346 (78.6) | 44 (80) | > 0.99 |

| Azithro | 387 (78.02) | 357 (81.1) | 30 (54.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 142 (28.6) | 131 (29.7) | 11 (20) | 0.155 |

| Remdesivir | 7 (1.41) | 6 (1.3) | 1 (1.8) | 0.564 |

| Interferon | 3 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (1.8) | 0.298 |

| Corton | 22 (4.4) | 8 (3.2) | 8 (14.5) | 0.001 |

| IVIG | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (1.8) | 0.210 |

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics, Radiographic, and Laboratory Results of Patients with COVID-19 a

To explore age‐related differences, a subgroup analysis was performed, stratifying age groups as ≤ 40, between 41 and 59, between 60 and 75, and > 75 years old. The final outcome was different among the age groups (P < 0.001). Older patients with COVID-19 had a higher proportion of comorbidities compared with younger patients. Hypertension was the most common comorbidity in the eldest three age groups (i.e., ≥ 41 years); nevertheless, it was less frequent in the patients aged ≤ 40 years (P < 0.0001). The distribution of other variables according to age groups has been presented in Table 2.

| Variables | < 40; n = 24 | 41 - 59; n = 165 | 60 - 75; n = 260 | 75 +; n = 51 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||||

| Gender | 0.864 | ||||

| Female | 12 (50) | 87 (52.7) | 139 (53.5) | 30 (58.8) | |

| Male | 12 (50) | 78 (47.3) | 121 (46.5) | 21 (41.2) | |

| Final status | < 0.001 | ||||

| Survived | 23 (95.8) | 156 (94.5) | 229 (88.1) | 37 (72.5) | |

| Dead | 1 (4.2) | 9 (5.5) | 31 (11.9) | 14 (27.5) | |

| Clinical history | |||||

| Diabetes | 1 (4.2) | 67 (40.6) | 136 (52.3) | 24 (47.1) | < 0.0001 |

| CVD | 2 (8.3) | 40 (24.2) | 113 (43.5) | 33 (64.7) | < 0.0001 |

| HTN | 1 (4.2) | 68 (41.2) | 158 (60.8) | 34 (66.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Cancer | 0 (0) | 6 (3.6) | 15 (5.8) | 2 (3.9) | 0.499 |

| Other disease | 6 (25) | 54 (32.7) | 117 (45) | 29 (56.9) | 0.003 |

| Number of comorbidites | < 0.0001 | ||||

| No disease | 11 (45.8) | 27 (16.4) | 13 (5) | 1 (2) | |

| 1 - 3 | 7 (29.2) | 108 (65.5) | 157 (60.4) | 26 (51) | |

| 4 - 6 | 6 (25) | 29 (17.6) | 90 (34.6) | 23 (45.1) | |

| 7 + | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |

| Diagnosis | |||||

| PCR result | 0.717 | ||||

| Positive | 19 (79.2) | 126 (77.8) | 198 (76.7) | 34 (68) | |

| Negative | 5 (20.8) | 36 (22.2) | 60 (23.3) | 16 (32) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 3 (1.8) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (2) | |

| CT result | 0.335 | ||||

| Positive | 22 (100) | 142 (91.6) | 210 (87.1) | 39 (79.6) | |

| Negative | 0 (0) | 7 (4.5) | 13 (5.4) | 5 (10.2) | |

| Suspicious | 0 (0) | 6 (3.9) | 18 (7.5) | 5 (10.2) | |

| Unknown | 2 (8.3) | 10 (6.1) | 19 (7.3) | 2 (3.9) | |

| Effective PCR result | 23 (95.8) | 156 (94.5) | 236 (90.8) | 46 (90.2) | 0.436 |

| Effective CT result | 22 (91.7) | 155 (93.9) | 236 (90.8) | 48 (94.1) | 0.636 |

| Effective clinical diagnosis | 10 (41.7) | 62 (37.6) | 77 (29.6) | 18 (35.3) | 0.285 |

| Effective laboratory results | 23 (95.8) | 159 (96.4) | 248 (95.4) | 47 (92.2) | 0.664 |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Fever | 16 (66.7) | 92 (55.8) | 115 (44.2) | 22 (43.1) | 0.028 |

| Cough | 11 (45.8) | 97 (58.8) | 120 (46.2) | 24 (47.1) | 0.074 |

| Dyspnea | 14 (58.3) | 91 (55.2) | 150 (57.7) | 25 (49) | 0.703 |

| Myoliagia | 5 (20.8) | 36 (21.8) | 31 (11.9) | 7 (13.7) | 0.045 |

| Anorexia | 4 (16.7) | 17 (10.3) | 29 (11.2) | 7 (13.7) | 0.766 |

| Diarrhea | 3 (12.5) | 8 (4.8) | 18 (6.9) | 1 (2) | 0.256 |

| Headache | 5 (20.8) | 6 (3.6) | 17 (6.5) | 1 (2) | 0.005 |

| Sore Throat | 0 (0) | 3 (1.8) | 8 (3.1) | 1 (2) | 0.710 |

| Olfactory dysfunction | 1 (4.2) | 4 (2.4) | 5 (1.9) | 2 (3.9) | 0.783 |

| Nausea | 2 (8.3) | 18 (10.9) | 24 (9.2) | 2 (3.9) | 0.513 |

| Fatigue | 5 (20.8) | 53 (32.1) | 75 (28.8) | 15 (29.4) | 0.691 |

| Other symptoms | 6 (25) | 29 (17.6) | 65 (25) | 11 (21.6) | 0.342 |

| Laboratory results | |||||

| Normal LDH | 6 (25) | 42 (25.5) | 58 (22.3) | 12 (23.5) | 0.923 |

| Lymph | 29.85 ± 15.01 | 25.81 ± 11.27 | 24.03 ± 13.89 | 20.64 ± 11.40 | 0.016 b |

| PMN | 54.58 ± 11.41 | 58.27 ± 12.15 | 57.25 ± 12.89 | 55.84 ± 14.53 | 0.457 b |

| Hb | 13.01 ± 1.78 | 12.38 ± 1.89 | 11.87 ± 1.97 | 11.71 ± 1.80 | 0.016 b |

| WBC | 7170.83 ± 2770.72 | 6837.03 ± 2926.97 | 8015.22 ± 4729.88 | 9570.59 ± 6511.01 | 0.006 b |

| Platelet | 201.70 ± 72.49 | 222.41 ± 79.74 | 213.18 ± 83.94 | 216.66 ± 77.24 | 0.347 b |

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics, Radiographic, and Laboratory Results of Patients with COVID-19 According to Different Age Groups

5. Discussion

Our study was conducted in a large tertiary center, the Naft Grand Hospital, in Southwestern Iran. Although this was a non-COVID center, in the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, several patients diagnosed with the COVID-19 infection were referred to the hospital. The most predominant comorbidity associated with COVID-19-related adverse events was hypertension, followed by diabetes. Our findings were in line with other recent reports. Sanyaolu et al., in a recent systematic review, examined comorbid conditions in the patients infected with the COVID-19 disease and reported hypertension followed by cardiovascular diseases and diabetes as the most common comorbidities identified in these patients (1). Richardson et al., in a large case series of patients with COVID-19, referred to 12 hospitals, reported the most common comorbidities as hypertension, obesity, and diabetes, respectively (6). One possible reason why individuals with hypertension are at a higher risk of death due to COVID-19 is that a well-functioning immune system can help people to better combat this disease without developing too many adverse effects (7). Another possible hypothetical reason is treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) (8), which increase the level of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) in the body. Although no scientific evidence has been provided so far, the SARS-CoV-2 virus attaches to the host’s cells via ACE2 (9).

Moreover, in the present study, most patients belonged to the age group of 60 to 75 years. As older adults are at a higher risk for severe complications than younger people; similarly, people at the age of 60 and above are generally more vulnerable to COVID-19-related severe adverse events. Perez-Saez et al. estimated a relatively high infection fatality risk (IFR) in the COVID-19 patients aged 65 years and older (10). Mueller et al., described molecular differences between younger and older individuals, as well as several biological age clocks and genetic differences that may explain why the chance of developing a severe form of COVID-19 increases with age (11). This fact can be explained by the physiological changes that occur with aging in the human body. In particular, the higher prevalence of comorbidities in older adults contributes to a low functional reserve that reduces the intrinsic ability and flexibility and impedes the capability of controlling the COVID-19 infection (12-14).

Most of our patients had positive RT-PCR and chest CT scan results. The difference between survivors and non-survivors was not statistically significant in terms of PCR and chest CT-scan results. Accordingly, it is recommended to confirm an ultimate COVID-19 diagnosis based on both RT-PCR and CT scan findings because none of the two detection techniques are reliable alone and may not reveal the severity of the disease (15, 16).

The most common symptoms observed in the referred patients in the present study were cough, dyspnea, and fever. Previous studies have reported fever in 99% of people during the COVID-19 disease. On the other hand, in a cohort study, it was reported that this complication at the time of referring to the hospital was present in only 44% of patients, and in some cases, it was reported in up to 89% of patients during hospitalization (17). Other common symptoms such as cough and shortness of breath may occur in 10% of COVID-19 patients (18).

In the present study, the most frequent medications included kaletra (lopinavir/ritonavir), azithromycin, and hydroxychloroquine, of which azithromycin was significantly more prescribed in the survivor than the non-survivor group. In this context, pervasive clinical evidence and existing literature on the antiviral mechanisms of lopinavir/ritonavir, hydroxychloroquine, and azithromycin in the treatment of previous epidemic viral diseases suggested that these combinations may be helpful in the fight against the COVID-19 infection (19-24). Available evidence suggests that these antiviral medications can target RNA polymerase, which blocks viral RNA synthesis, and chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLpro), a major coronavirus protease (25, 26). Nevertheless, the clinical efficacy of these drugs is controversial (27).

5.1. Conclusion

Most referred cases were survivors with mild to moderate symptoms, and a few of them, unfortunately, succumbed to the disease. This can be due to the fact that people with mild COVID-19 symptoms may respond well to the treatment and institutional isolation. The COVID-19 disease not only has created a global epidemic that has had a major impact on public health and changed the daily lives of billions of people, but it has also revealed the weaknesses of apparently strong and well-resourced international health systems. Moreover, it has inflicted a wide and sometimes irreparable economic impact. Advances in medical diagnosis and treatment, such as designing new and rapid diagnostic kits and effective targeted treatments, as well as developing efficient vaccines, are among the priorities that have received much attention during the pandemic. At the same time, good and evidence-based clinical care combined with strict public health interventions would save the lives of thousands, if not millions, worldwide.