1. Background

Fungi which produce several metabolites develop rapidly on different kinds of food and food products (1). These microorganisms can easily spread by wind, insects and rain (2). So far scientific studies have shown that various fungal species as much as 100000 are regarded as typical contaminants of food and agricultural crops (3). Molds naturally yield a wide range of metabolites which are called mycotoxins. Mycotoxins can cause toxic effects on human and animal tissue and organs (4). They are among the 21st century major concerns due to their important pathogenic role (5, 6). According to the previous studies, A. Rhizopus and Penicillium spp. are common molds in nuts, dried fruits and foodstuff (7, 8).

Fungal contamination in nuts due to Penicillium spp., Aspergillus, Fusarium spp., Trichoderma spp. and Cladosporium spp. have been reported from America, Brazil and western Africa (9, 10). Food contamination with Aspergillus was first reported for pepper and then for other foodstuff such as nuts (11). An Iranian study indicated that 30% of pistachio and 36.1% of peanut products were contaminated with Penicillium spp. and Aspergillus, respectively (1). Various epidemiologic studies have indicated that fungus, especially species that produce aflatoxin, cause human gastrointestinal disorders, hepatic neoplasm, and liver cell carcinoma (4, 12). These days prevention of fungal contamination in foodstuffs especially nuts has become a public health issue (13).

In some Asian and African countries, 30.97 million tons of the greasy products especially peanuts and pistachios are spoiled by A. flavus and A. niger (1). Fungal infestation happens during or after harvesting, storage and transition (14). Some important factors such as storage temperature, amount of moisture, oxygen existence and composition of gaseous compounds can affect the growth of mold during storage (15). However, several countries have tried to control the levels of mycotoxins, particularly aflatoxin in food and agricultural products, but sometimes it is difficult to deal with certain factors to lower levels of aflatoxin (16). In some countries such as Iran, production and consumption of nuts (untreated and roasted with salt) has increased (17, 18). Since nuts are known as a healthy food and have a pleasant taste, people have a great tendency to consume them instead of other snacks such as chips and popcorn (19).

2. Objectives

Fungal contamination is currently regarded as a public health concern and there is a global trend to reduce the resulting health problems. Moreover, considering the fact that nuts consumption is high in Iran (1), the aim of this study was to determine the contaminant microflora of Iranian nuts such as untreated and roasted with salt pistachios, peanuts and also untreated walnuts.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Samples

During the fall of 2011, 100 samples of each untreated nuts (pistachios, walnuts and peanuts) and 50 samples of each roasted with salt nuts (pistachios and peanuts) were collected randomly (area sampling) from deferent parts of the city (50 gr), transported in sterile packets to the laboratory and kept in a cool place (3 - 5ºC) for a maximum of three days. Nuts were surface-sterilised in 4% sodium hypochlorite for 2 minutes, diluted with distilled water three times to reach a concentration of 2%, rinsed in 100 mL distilled water and then let dry.

3.2. Mold Identification

Nuts were cultured on Sabouraud’s 4% dextrose agar (SDA, Merk, Germany) prior to incubation at 25ºC for 7 - 15 days and then examined daily for fungi growth. Taxonomic identification of fungi colonies was carried out by morphological, macro and microscopic characteristic, according to standard methods (20, 21). When necessary, culturing was repeated using other mediums (Czapel-Dex Agar (Oxoid - CM97, UK), Malt extract Agar (Oxoid - L39, UK) or APFA Agar (Oxoid- CM0731, UK)) for exact identification.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

For statistical analysis SPSS version 11.5 (SPSS Institute Inc. Chicago, Illinois) was used. Descriptive statistical analysis including mean ± SD for fungi number, frequency and percentage for determination of fungal contamination were used. Comparison of percentages was done by statistics calculation software that was downloaded from www.statpac.com.

4. Results

A. niger and Mucor were the predominant molds observed among the roasted with salt and untreated nuts. In addition, in the untreated group, Penicillium spp. (25.3%), Helminthosporium spp. (20%) and Acremonium spp. (15%) were prevalent and in the roasted group A. fumigatus (14%) was found in considerable amounts. Bacterial contamination in the roasted group (31%) was more than the untreated group (3%). According to Table 1, fungal contamination in the untreated group was higher than the roasted group.

| Fungi | Roasted With Salt, No. (%) | Untreated, No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus spp. | 35 (35) | 163 (54.3) |

| Mucora | 14 (14) | 188 (62.7) |

| A. nigera | 14 (14) | 132 (44) |

| A. fumigatusa | 13 (13) | 8 (2.7) |

| Penicillium spp.a | 8 (8) | 76 (25.3) |

| A. flavus | 5 (5) | 18 (6) |

| A. ochraceusa | 2 (2) | 0 |

| Helminthosporium spp.a | 3 (3) | 60 (20) |

| Acremonium spp.a | 2 (2) | 45 (15) |

| Gliocladium spp. | 1 (1) | 9 (3) |

| Trichoderma spp. | 2 (2) | 6 (2) |

| Geotrichum Candidum | 3 (3) | 3 (1) |

| Candida albicans | 2 (2) | 1 (0.3) |

| Cladosporium spp.a | 3 (3) | 0 |

| A. albidus | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Bactriaa | 31 (31) | 9 (3) |

| A.terreus | 0 | 5 (1.7) |

| Drechslera spp. | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Stachybotrys spp. | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Fusarium spp. | 0 | 2 (0.7) |

| Rhodotorula Rubra | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

a P Value ≤ 0.05

Table 2 shows the percentage of roasted and untreated nuts samples that were contaminated by fungi. In salty pistachios and peanuts, the most prevalent fungi were A. fumigatus (14%) and Penicillium spp. (14%) while in untreated peanuts, pistachios and walnuts, A. niger was predominant (14%, 62%, 41%, respectively). Percentages of Aspergillus genus were 54.3% and 35% for untreated samples and roasted with salt samples, respectively (P < 0.001). Bacterial contamination was 3% in untreated and 31% in roasted samples (P ≤ 0.001). There was a significant contamination in roasted with salt pistachio samples (50%).

| Fungi | Untreated pistachios | Roasted pistachios | Untreated peanuts | Roasted peanuts | Untreated walnuts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus spp. | 79 | 24 | 19 | 46 | 71 |

| Mucor | 38 | 4 | 84 | 24 | 66 |

| Penicillium spp. | 22 | 2 | 13 | 14 | 41 |

| A. niger | 62 | 8 | 14 | 20 | 56 |

| A. flavus | 6 | 0 | 3 | 10 | 9 |

| A. fumigatus | 5 | 14 | 0 | 12 | 3 |

| A. ochraceus | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Helminthosporium spp. | 39 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 15 |

| Acremonium spp. | 23 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 20 |

| Gliocladium spp. | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Trichoderma spp. | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Bactria | 5 | 50 | 0 | 12 | 4 |

| Other fungus | 5 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

According to Table 3, the most and the least mold contaminated nuts were walnuts (mean: 2.2 ± 0.98) and roasted with salt pistachios (mean: 0.38 ± 0.60), respectively.

| Nuts | Mean ± SD | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Untreated walnuts | 2.2 ± 0.98 | 1 - 5 |

| Untreated pistachios | 2.1 ± 1.08 | 1 - 6 |

| Untreated peanuts | 1.29 ± 0.64 | 0 - 3 |

| Roasted pistachios | 0.38 ± 0.60 | 0 - 3 |

| Roasted peanuts | 0.98 ± 0.76 | 0 - 3 |

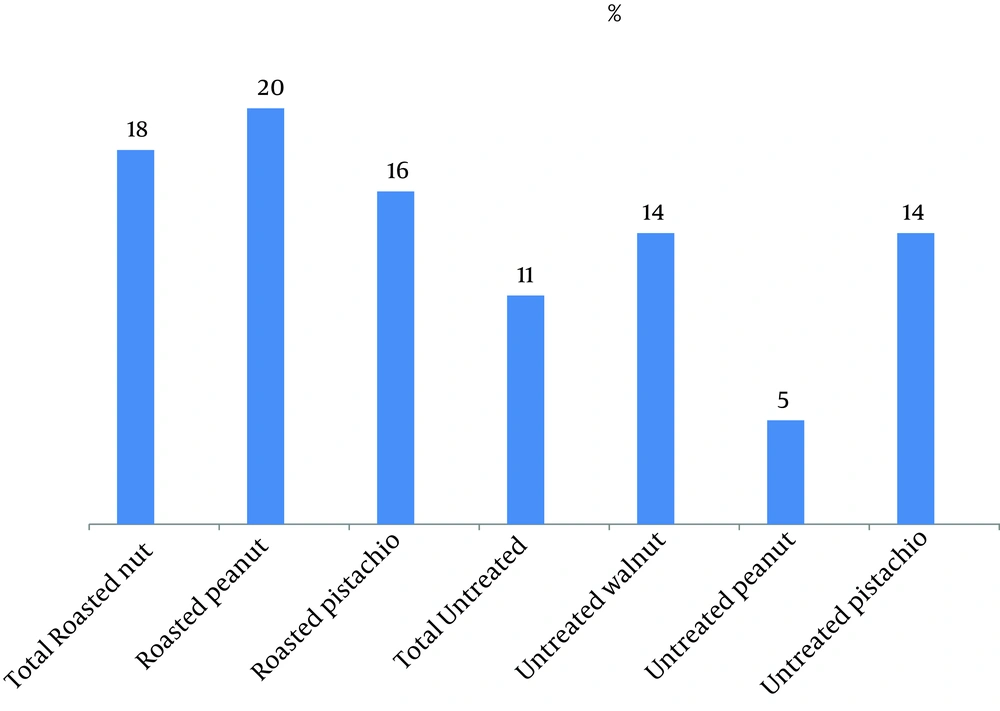

According to Table 2, Aspergillus genus frequency was 79% in untreated pistachios and 71% in walnut samples, while contamination with this genus in untreated peanuts was 19%. A. niger was the predominant fungi in all untreated and roasted with salt peanut samples, while A. fumigates was prevalent in roasted with salt pistachios. Distinctive mycotoxigenic molds in the present study included A. flavus , A. fumigatus , A. terreus , A. ochraceus , Penicillium spp., Gliocladium spp., Fusarium spp., and Stachybotrys spp. and Figure 1 shows the contamination percentage of these fungi in samples. Percentage of mycotoxigenic fungal contamination in roasted samples (18%) was more than untreated samples (11%); this was considerable although not significant (P = 0.069). Fungal contamination in roasted samples was lower than untreated nuts. This reduction was significant for some types of fungi (P < 0.05) ( Penicillium spp., A. niger , A. fumigatus , Acremonium spp., Helminthosporium spp., Cladosporium spp., A. ochraceus ).

5. Discussion

Fungi accidently contaminate and decay food and food products (22). Fungal contamination of edible greasy seeds and nuts were reported from different countries (1). The obtained results show that the most dominant fungal genera in untreated and roasted with salt peanuts was A. niger, contaminating 14% of untreated and 20% of roasted with salt samples. In contrast to the findings of Hedayati, Gurses, Khomeiri, Vaamonde and Nakai, the present results showed that A. niger was prevalent in peanuts (both untreated and roasted with salt), whereas in their studies A. flavus was dominant (23-27). Furthermore, Hedayeti's study identified three strains of Aspergillus from peanut samples, namely A. flavus, A. niger and A. fumigatus (23).

The results of another study on fungal contamination of peanuts in Zanjan Bazar (Iran) in comparison to Tabriz markets are shown in Table 4. Fungal contamination of peanuts in Tabriz is less than the Bazar of Zanjan (28). This can be the result of suitable conditions for the growth of fungi in the Bazar of Zanjan such as high temperature, high relative humidity, low light intensity, long-term storage and the natural fungal content of soil (29). Contamination of dried nuts such as peanuts, walnuts, and pistachios with mycotoxigenic species occurs generally during the harvest procedure and storage (24).

| Fungal Contamination | Zanjan | Tabriz | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | Salted | Untreated | Salted | |

| A. niger | 62.5% | 90% | 14% | 20% |

| Penicillium spp. | 6.2% | 40% | 13% | 14% |

| A. flavus | 93.7% | 60% | 3% | 10% |

It seems that low fungal contamination in this study may be due to the nuts being fresh, because peanuts used in the present study were purchased during the harvesting season. Research on Egyptian peanuts showed that A. niger was the dominant mold in salted peanut samples (28.1%) which was similar to our results about roasted peanuts (20%); also in untreated samples Penicillium spp. (24%) was more than the present study (13%) (30). In the present study the predominant fungi in untreated pistachio samples were Aspergillus spp. (78%), Helminthosporium spp. (39%), Acremonium spp. (23%), Penicillium (22%) and Mucor (38%), while in roasted with salt pistachios, Aspergillus spp. (24%) and Cladosporium spp. (16%) were prevalent. Among the Aspergillus family, A. niger with 62% contamination was prevalent in untreated pistachios, but in roasted with salt pistachios, A. fumigatus with 14% contamination was dominant.

The isolation of Aspergillus spp. agrees with the findings of other researchers evaluating peanuts in tropical areas (31, 32). The prevalence of Aspergillus may be because of the climatic conditions of these countries, which can be appropriate for the development of fungi like Aspergillus (33). A study by Fernane reported that contamination by A. niger (34) was 30% which is less than Tabriz untreated and roasted with salt pistachios with 62% and 8% contamination rate, respectively. Furthermore, as reported by Fernane, pistachios contamination by Penicillium spp. was 38% and more than untreated and roasted with salt pistachios contamination in samples of Tabriz markets. Also Shahidi reported that 12.5% of pistachio samples were contaminated by Aspergillus species (35). The results of another study on pistachios fungal contamination in America showed that Aspergillus spp. with 94.5% contamination rate was the dominant fungi (36).

A. niger was the most frequently isolated mold in walnuts, contaminating 56% of walnut samples. Walnut contamination by this fungus was less than that of Saudi Arabia (78.5%) (13). The excessive growth of Aspergillus spp. may be due to the fact that this genus is regarded as a storage mold while Fusarium spp. is considered as a field fungus (33). High fungal contamination in walnuts may be due to the fact that, all walnut samples were without shells (12). Also some samples had been damaged, thus this factor beside others mentioned above may facilitate the fungal growth on nuts (7, 27, 28).

Some explanations for the low contamination of roasted samples can be suggested. Firstly, salt on nuts is an important factor which prevents the growth of different fungi (37, 38). Secondly, low moisture content of salted and roasted nuts is a preventive factor of mold growth. Thirdly, it seems that high temperature during roasting of nuts can reduce fungal contamination of nuts (39, 40). Results of this study showed that contamination with Mucor was prevalent especially in untreated nuts. Even though this fungus is not a mycotoxigenic fungi, contamination with this microorganism should be monitored for maintenance of foodstuff hygiene and safety. Furthermore, it is suggested that high microbial contamination of roasted with salt samples should be further studied.

According to the results of the present study, incidence of fungal contamination in nuts with Aspergillus family and mycotoxigenic molds is high; on the other hand, nuts are considered as an Iranian favorite snack due to their notable health effects. Since consumption of contaminated nuts for long periods has carcinogenic and toxigenic effects on human health, hence government authorities should monitor and set suitable guidelines for food safety, furthermore take steps to educate people about the dangers of toxigenic molds and promote the health knowledge for people to select safe foods.