1. Background

Acetaminophen (APAP) is one of the most common over-the-counter antipyretic/analgesic medications for fever or pain (1, 2). Although acute overdose or cumulative chronic use of APAP is well tolerated at typical therapeutic doses, it can also lead to severe hepatic necrosis and acute liver failure (3-5).

At therapeutic levels in body cells, APAP is converted by cytochrome P450 (CYP450) isoforms (CYP2E1, CYP3A4, and CYP1A2) to the reactive metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI), which is subsequently detoxified by hepatic glutathione (5, 6). However, when taken in overdose, this metabolite reduces liver glutathione (GSH) reserves. It binds to various mitochondrial macromolecules (DNA, lipids, and cysteine groups in proteins), leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), especially superoxide anions. Finally, impaired mitochondrial respiration and oxidation of lipids and other molecules, along with the death of hepatocytes and activated inflammatory cells, lead to hepatocyte necrosis and liver damage (7-10).

The only treatment for APAP-induced hepatotoxicity is N-acetylcysteine (NAC). This substance can prevent liver damage by restoring GSH. However, because of its adverse effects and narrow therapeutic window, it is vital to find new agents superior to NAC in terms of effectiveness and safety (11-13). In recent years, there has been a growing interest in discovering and developing harmless and efficient natural products against APAP-induced hepatotoxicity. Antioxidant phytochemicals can delay or inhibit oxidative stress by preventing the initiation or propagation of oxidative chain reactions (14, 15).

Flavonoids are phenolic compounds that exert their antioxidant activity by modulating different signaling pathways (16, 17). Biochanin A (BA) is an O-methylated flavonoid in various plants, such as red clover, alfalfa sprouts, and peanuts (18, 19). A broad spectrum of pharmacological properties has been reported for BA, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, antineoplastic, carcinogenic, and hypolipidemic effects (18, 20).

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to assess the effects of BA on acetaminophen-induced liver toxicity in mice.

3. Methods

3.1. Chemicals

BA, APAP, and DTNB were prepared from Sigma Chemical Co. (USA). Thiobarbituric acid (TBA) was prepared by Merck Company. The rest of the chemicals used in this study were purchased from local firms in Iran and were of analytical grade.

3.2. Animal Experiments

Adult male Naval Medical Research Institute (NMRI) mice (weighing 25 - 30 g) were used for this study. The study was approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (ethical approval ID: IR.AJUMS.ABHC.REC.1397.066). APAP and BA were dissolved in warm saline and 1% DMSO solutions, respectively. The animals were randomly divided into six groups (seven animals in each group): Group 1 received normal saline (NA, gavage) and was used as control; group 2 was exposed to BA alone (40 mg/kg, oral); group 3 received APAP alone (300 mg/kg); and groups 4, 5, and 6 were co-treated by APAP and BA at doses of 10, 20, and 40 mg/kg, respectively. BA was administered before and 2 and 4 hours after APAP (11, 18).

3.3. Biochemical Blood Tests

Seven hours after the end of treatment, the animals were sacrificed after a night of fasting. For biochemical tests, the blood was immediately collected in the anticoagulant tubes and centrifuged for 15 min at 2000 g to obtain serum. Serum samples were used to investigate liver biomarkers, such as alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP).

3.4. Liver Tissue Lipid Peroxidation Assay

The lipid peroxidation rate in the liver was calculated by forming TBA reactive materials. The liver tissue was added to TBA and then centrifuged for 15 min. After adding TBA, the samples were placed in the water bath. Finally, the absorbance of the samples was read at 532 nm, and the lipid peroxidation rate was reported as nmol/mg protein (18).

3.5. Determination of Liver Tissue Antioxidants Assay

Reduced GSH content was measured in the liver using DTNB as an indicator. Briefly, the liver tissue specimens were homogenized in phosphate buffer. Tissue homogenates were mixed with TCA and centrifuged. Supernatant fractions were mixed with phosphate buffer and DTNB solution. The produced yellow color was read by a spectrophotometer at 412 nm. The GSH content was calculated according to a standard curve and was expressed as nmol/mg protein (18). Superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) activities were measured according to the manufacturer’s protocol of the ZellBio kit (ZellBio GmbH, Germany). The results were reported as U/mg protein.

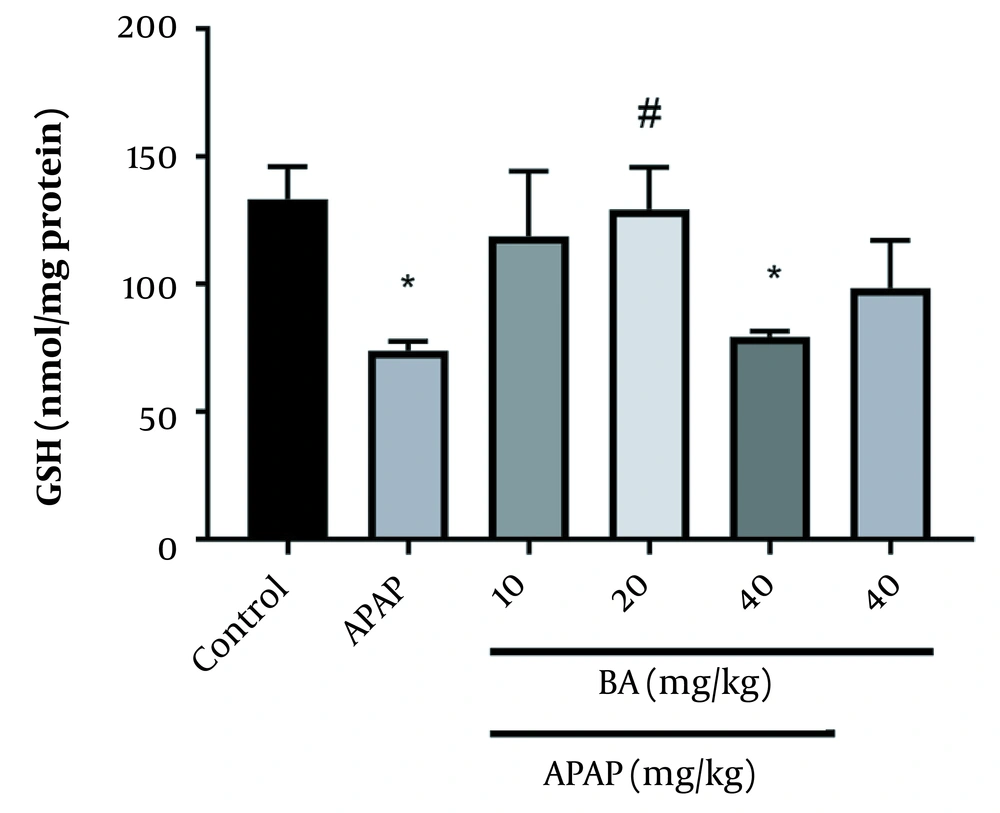

3.6. Histopathological Evaluation

After fixing the liver tissue in formalin solution, dehydrating it in graded alcohol concentrations, embedding it in paraffin, and preparing 4 - 6 micrometers sections, the samples were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Histological changes, such as fat deposition in liver cells, congestion of red blood cells (RBCs), infiltration of inflammatory cells, and central lobular necrosis, were examined in microscopic slides. Histological characteristics were graded into four categories normal (0), weak (1), moderate (2), or severe (3), and the averages were considered (11).

3.7. Statistical Analysis

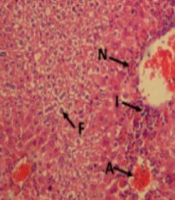

Descriptive results are provided as mean ± SEM. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s post hoc analysis were applied to compare the groups. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. In each group, n = 7 and *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 indicate significant difference from the control group, and #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 and ###P < 0.001 indicate significant difference from the APAP group.

4. Results

4.1. Biochemical Blood Tests

As shown in Figure 1, APAP significantly increased ALP, AST, and ALT levels in the toxic group compared to the NA group. Pre-treatment by BA caused a marked decrease in the levels of ALP, AST, and ALT that were raised by APAP. Moreover, the most significant change was observed at the dose of 20 mg/kg (P < 0.05). In addition, the administration of BA alone (40 mg/kg) showed a toxic effect on the AST level compared to the control group.

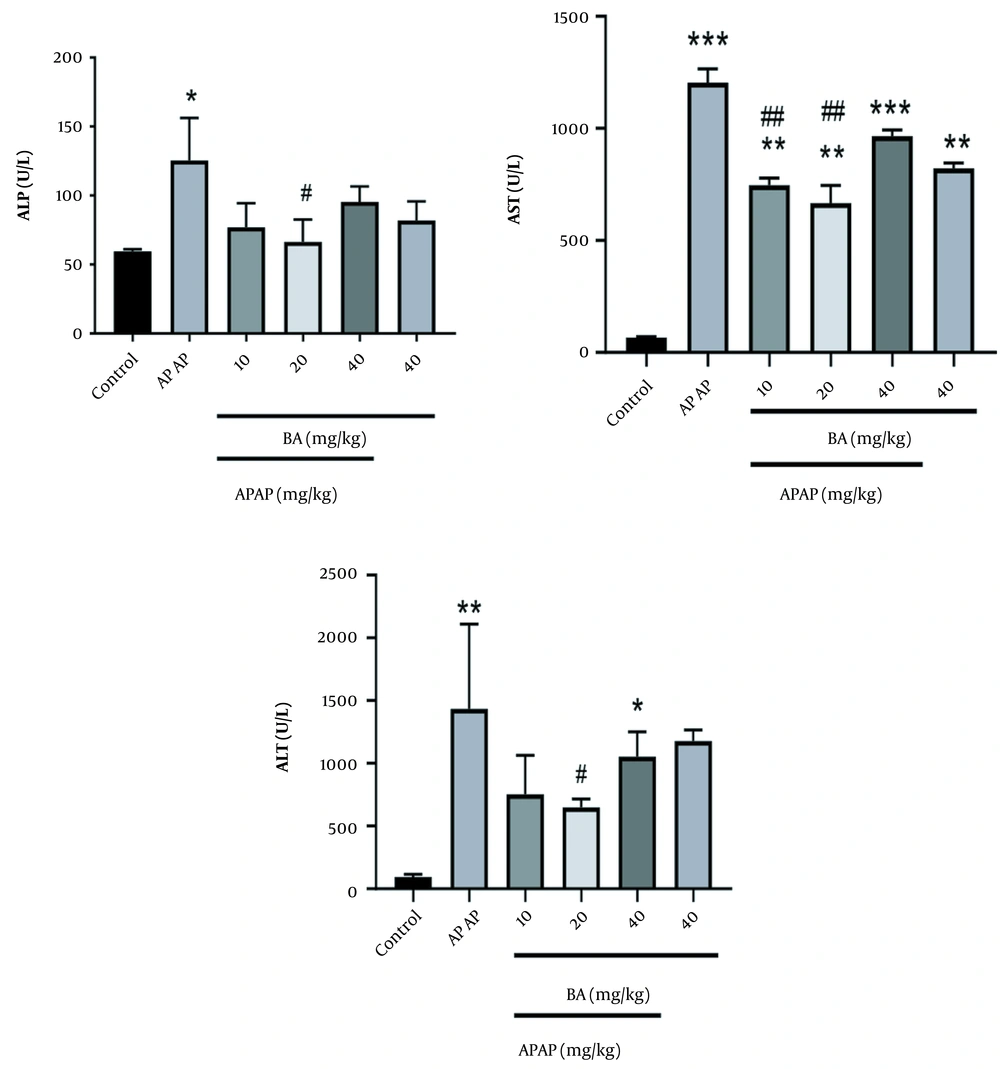

4.2. Liver Tissue Lipid Peroxidation Assay

Gavage administration of APAP significantly raised the malondialdehyde (MDA) level compared to the control group (P = 0.01). However, BA (10 and 20 mg/kg) caused a significant reduction in MDA level in comparison with the APAP group (P = 0.01 and P = 0.001, respectively) (Figure 2).

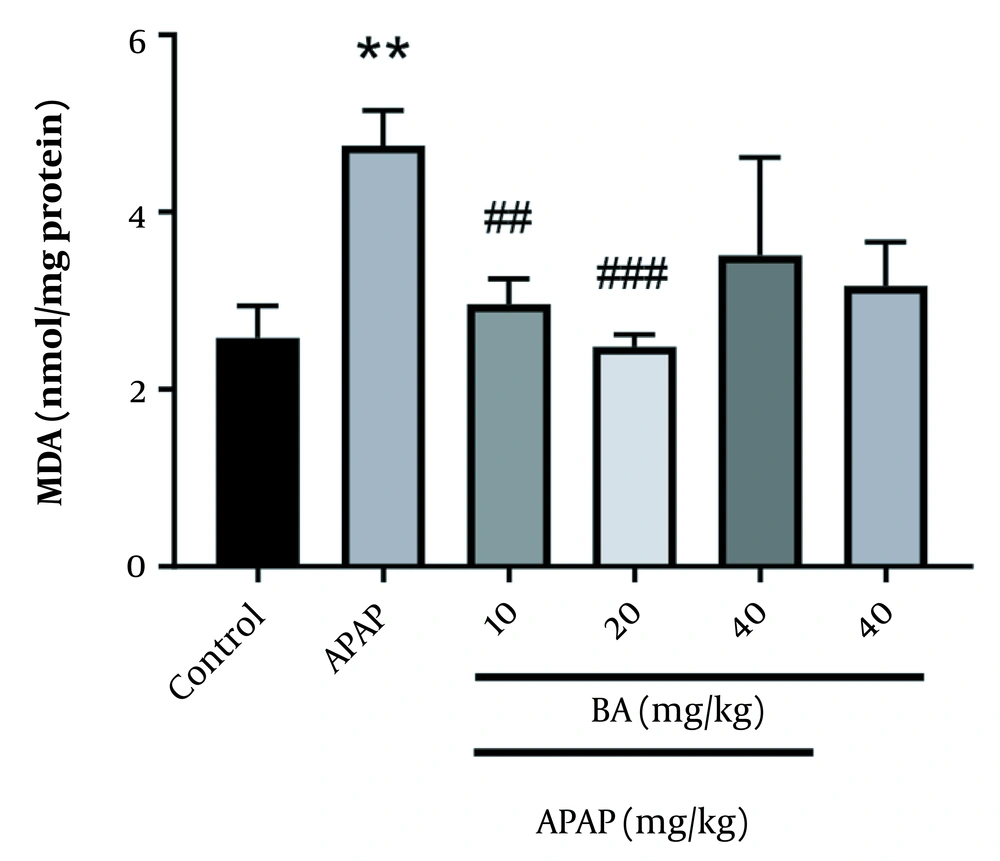

4.3. Determination of Reduced Glutathione Level

Figure 3 displays the GSH concentrations in the livers of various animal groups. Compared to the control group, GSH levels were significantly lower after APAP treatment (P < 0.05). In comparison with the control animals, GSH levels were lower after receiving 40 mg/kg of BA (P < 0.05). The APAP groups (20 mg/kg) treated with BA and the APAP group were significantly different in terms of the GSH levels.

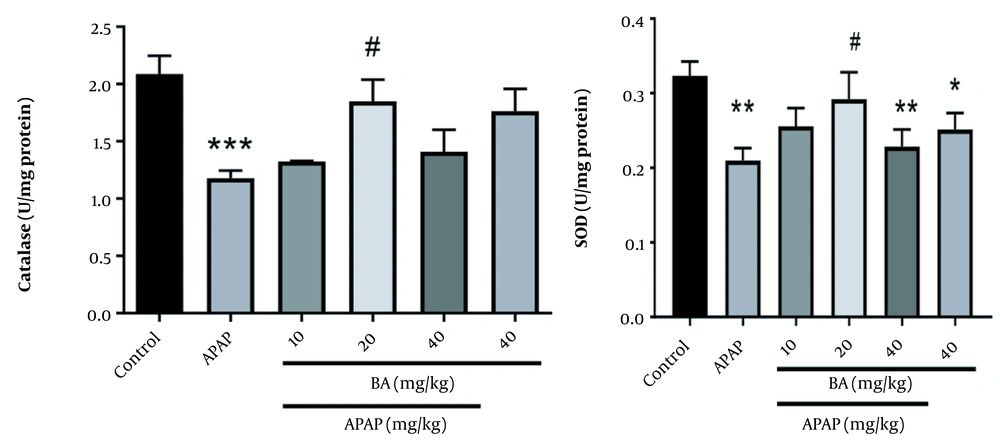

4.4. Antioxidant Enzymes Assessments

We observed a statistically significant difference in the catalase enzyme activity between the APAP-treated and control groups (P < 0.001). The APAP group treated with BA (20 mg/kg) showed a significant increase in catalase enzyme activity compared to the control group (P < 0.001). A marked reduction was found in the hepatic content of SOD in the animals treated with APAP alone, APAP + BA, and BA alone (40 mg/kg) (P < 0.01, P < 0.01, and P < 0.05, respectively). BA at the dose of 20 mg/kg reduced the hepatic content of SOD in mice treated with a combination of BA and APAP compared to animals treated only with APAP (Figure 4).

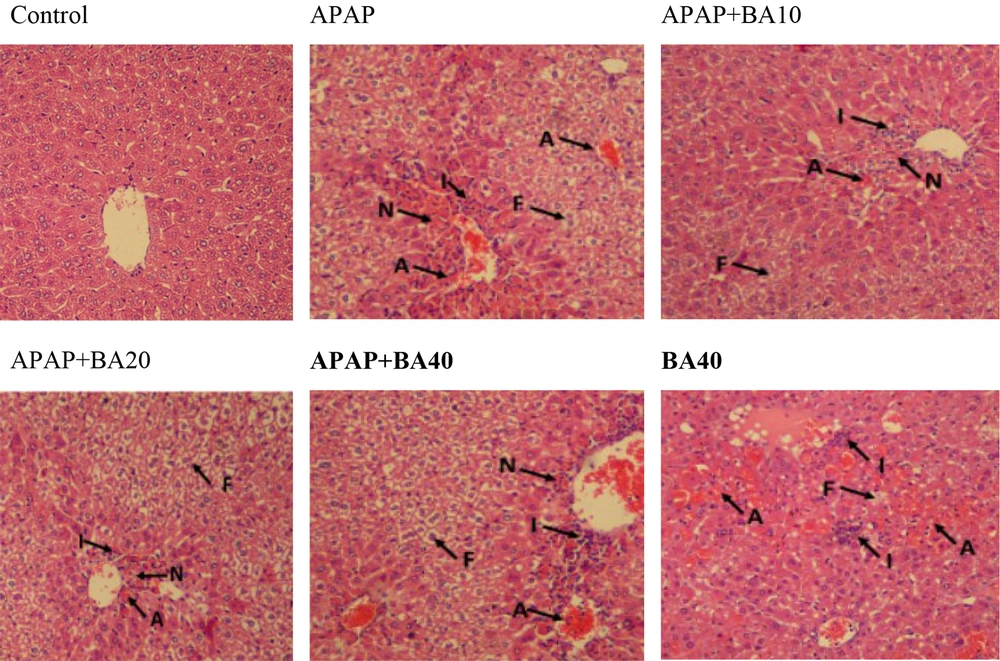

4.5. Histopathological Evaluation

Using H&E histological examination, the presence of APAP-induced hepatotoxicity was approved. The H&E staining of liver tissue sampled from mice showed inflammation, acinar necrosis, and hepatocyte necrosis. Moreover, during the histological analysis, fat deposits were observed. In contrast, BA at 10 and 20 mg/kg doses significantly restored hepatocellular damage brought on by APAP (Figure 5 and Table 1).

| Groups | Histological Criteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBCs Congestion | Inflammation | Fat Deposit | Necrosis | |

| Control | 0.13 ± 0.00 | 0.12 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| APAP | 2.26 ± 0.33 *** | 2.23 ± .34 *** | 2.13 ± 0.22 *** | 2.46 ± 0.42 *** |

| APAP + BA10 | 0.52 ± 0.08 **## | 0.41 ± 0.09 **## | 0.36 ± 0.05 ***## | 0.32 ± 0.06 ***## |

| APAP + BA20 | 0.61 ± 0.24 **## | 0.56 ± 0.00 **## | 2.05 ± 0.29 *** | 0.37 ± 0.35 ***## |

| APAP + BA40 | 2.42 ± 0.36 *** | 2.73 ± 0.25 *** | 2.47 ± 0.41 ** | 2.67 ± 0.32 *** |

| BA40 | 1.92 ± 0.26 *** | 1.03 ± 0.15 *** | 0.51 ± 0.14 *** | 0.08 ± 0.00 *** |

Abbreviations: RBC, red blood cells; APAP, acetaminophen; BA10, biochanin A 10 mg/kg; BA20, biochanin A 20 mg/kg; BA40, biochanin A 40 mg/kg

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD. In each group, n = 7 and *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 indicate significant difference from the control group, and #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 and ###P < 0.001 indicate significant difference from the APAP group.

5. Discussion

The liver is recognized as the vital organ that controls the metabolism of lipids, glucose, and energy (21). The liver tissue of APAP-treated animals underwent a histological analysis, which demonstrated histopathological alterations linked to hepatic toxicity. Oxidative stress, APAP-induced lipid peroxidation, and the consequent disturbance of liver function and structure may be attributed to the damage to liver tissue (22). By pretreating mice with BA (10 and 20 mg/kg), the histological damages, such as necrosis, inflammatory RBC congestion, and fat deposit, were also noticeably reduced. One potential mechanism is that BA scavenges ROS in order to suppress them (20).

The BA-treated group showed substantial histological alterations. Similar findings have already been published (19, 23). The ALP, ALT, and AST activities are regarded as sensitive markers of liver damage (24). Numerous investigations have revealed increased liver-associated enzyme activity in the plasma of animals exposed to APAP (25, 26). According to our findings, which were in line with those of earlier studies, serum levels of ALP, ALT, and AST were elevated in animals exposed to APAP. This may be primarily because of cellular leakage into the blood as a result of the loss of functional integrity of the hepatic membrane, nuclear DNA damage, and subsequent cell death (27).

Comparing the APAP-induced animal with the control group, the oral administration of BA, especially at a dose of 20 mg/kg, dramatically reversed these changes, demonstrating cellular integrity preservation and membrane protective effects, which finally prevent the leakage of cytoplasmic enzymes and components into the serum and cell death (18, 28). According to earlier studies, APAP has a negative effect on the hepatic tissue. Our findings that APAP 300 mg/kg increased the development of MDA in the liver support those findings (29, 30). In this regard, we demonstrated that treatment with BA (10 and 20 mg/kg) significantly reduced MDA levels in mice treated with APAP, which could be related to the ability of BA to scavenge free radicals and inhibit inflammation and oxidative stress (31, 32).

Enzymatic antioxidants SOD and CAT neutralize free radicals generated during oxidative stress. SOD catalyzes the conversion of H2O2 into water and oxygen, which is then deactivated by CAT (33). According to the available data, the livers of mice treated with APAP had considerably reduced levels of oxidative stress enzymes SOD and CAT because of increased superoxide radical anions generation and insufficient NADPH reserves (34, 35). Numerous animal studies have indicated that BA can prevent oxidative liver damage, which may result from effective free radical scavenging abilities and the potential to boost CAT and SOD activity (18, 19).

Our results showed that administering BA at a dose of 20 mg/kg significantly increased SOD and CAT activities in APAP-exposed animals, consistent with earlier findings. Furthermore, we observed that the liver function of animals given APAP alone or combined with BA 40 mg/kg had considerably decreased CAT and SOD activities. The latter finding could be attributed to BA metabolism. BA is first converted into genistein in the body. In addition, large amounts of BA are converted to both genistein and daidzein. Daidzin has a weak antioxidant effect and can cause oxidative stress by producing free radicals (18). Compared to the control group in this investigation, APAP therapy reduced liver GSH concentration. Potent antioxidants, such as GSH, are essential for maintaining the decreased cell state, and their significant depletion increases ROS and modifies apoptosis (36, 37). Our results revealed that BA considerably affected the GSH levels in animals exposed to APAP.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, our results indicated that BA at an optimal dose (low dose) could be protective against APAP-induced hepatic injury in mice. Protection may be due to its ability to reverse the imbalance between free radical production and degradation by antioxidant systems with an increased accumulation of ROS in the liver tissue, subsequently improving liver inflammation.