1. Background

Postpartum depression (PPD) refers to the depressive mood experienced after childbirth. It includes, but is not limited to, feelings of extreme sadness, anxiety, decreased energy, sleep disturbances, and changes in appetite (1). The global prevalence of PPD is 13.9%, having increased from 9.4% in 2010 to 19.3% in 2021 (2). The prevalence of PPD in Iran is also on the rise. A 2019 study showed that 38.8% of Iranian women experienced PPD (3), while another study indicated that during the COVID-19 pandemic, this rate rose to 68.2% (4). Postpartum depression can negatively affect the physical and psychological health of the mother, her marital relationship, and increase risky behaviors such as suicide, which can endanger the lives of both the mother and her baby (5). Some consequences of PPD for the neonate and infant include impaired mother-infant interaction, impaired cognitive development, and reduced exclusive breastfeeding (6).

Antidepressant medications are recommended for severe PPD. However, these medications are usually associated with side effects such as nausea, vomiting, sleepiness, lightheadedness, hypertension, dissociation, increased heart rate, and visual changes (7). Non-pharmacological treatments recommended for PPD include talk therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and mindfulness-based interventions (8). Herbal medicines such as lavender and aromatherapy, with or without massage, have also shown beneficial effects on PPD (9).

Chamomile is a traditional medicine containing terpenoids and flavonoids that can be effective in treating inflammation, muscle spasms, insomnia, and rheumatic pain (10). Amsterdam et al. reported that chamomile has anti-anxiety and antidepressant effects, finding it effective in participants with generalized anxiety disorder (11). Additionally, a study by Chang and Chen found that chamomile tea could significantly reduce scores of sleep insufficiency and depression, though these effects were limited to immediate use and did not last after four weeks of intervention (12). Another study showed that chamomile tea could significantly reduce anxiety and depression levels in postmenopausal women (13). Chamomile's anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-allergic, and antimicrobial activities have also been reported in other studies (14-17). Despite previous studies showing the effect of chamomile on anxiety and depression among various participants, evidence about its impact on postpartum women is rare.

2. Objectives

Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the effect of taking chamomile capsules on the improvement of PPD in Iran.

3. Methods

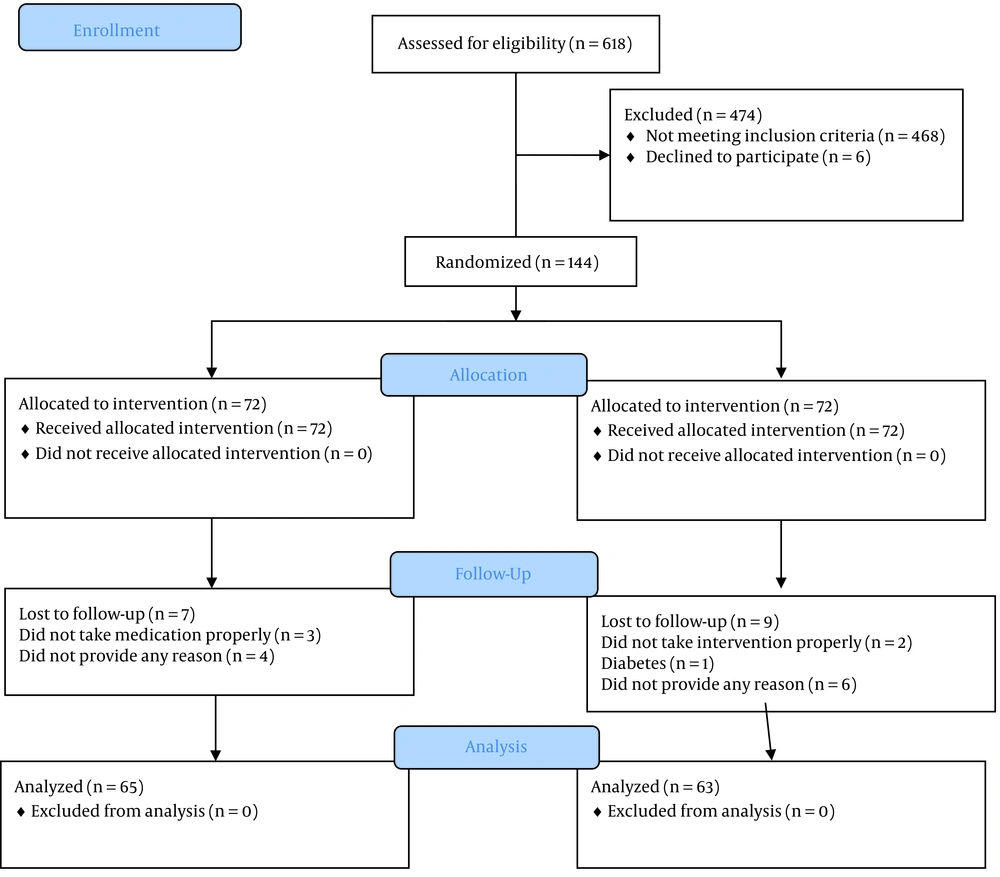

This randomized controlled trial was conducted with the participation of 144 women who had PPD. The study design was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (ref No: IR.AJUMS.REC.1400.523), and the protocol was registered in the Iranian Registry for Randomized Controlled Trials (ref No: IRCT20211207053313N1). All women provided written informed consent before data collection. Data collection started in March and was completed in July 2023.

3.1. Sample Size

Considering a previous study (12) and using the following formula, the sample size was calculated to be 65 for each group, intervention and control. Adding 10% to account for the attrition rate, the final sample size was determined to be 72 in each group.

Control-group mean (¯x1) = 9.51

Experimental group mean (¯x2) = 7.26

Control group standard deviation (s1) = 4.154

Experimental group standard deviation (s2) = 4.361

Significance level (α) = 0.05

Power of study (1-β) = 0.85

z 1-α/2= 1.96

z 1-β = 1.04

3.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Women were eligible to participate in the study if they met the following criteria: They were between two weeks to six months postpartum, had moderate or mild PPD, were of reproductive age (18 - 45 years), had basic literacy, and had given birth to a singleton, living baby. Women suffering from liver or kidney disease, stroke, high blood pressure, diabetes, allergy to chamomile, severe PPD, or those who were under medication for their depression were excluded from the study.

3.3. Randomization, Allocation Concealment and Blinding

A block randomization method with a block size of six and an allocation ratio of 1:1 was used for randomization. The codes were kept in sealed opaque envelopes until the time of intervention. Therefore, neither the researchers nor the participants were aware of group allocation. This was a double-blind randomized study, as the coding of chamomile capsules and the placebo was done by the pharmacist, and both the researchers and the participants were unaware of the content of the drug containers.

3.4. Setting

The postpartum women were screened and recruited from four public health centers in Dezful, Iran (No 1, 4, 2, and Teacher’s Health center).

3.5. Instruments

A demographic questionnaire and Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI-II) were used to collect the data. The demographic questionnaire contained questions about age, education, occupation, economic status, mode of delivery, intention for pregnancy, husband's age, educational attainment, and occupation. The content validity of this questionnaire was confirmed by five faculty members.

Developed by Aaron Beck, BDI-II is a 21-item multiple-choice questionnaire that measures the severity of depression. BDI-II assesses the participant's feelings over the past week. Each question is scored from 0 (indicating no sad feelings) to 3 (indicating unbearable sad feelings). The cut-off points for this questionnaire are as follows: 0 - 9 indicating minimal depression, 10 - 18 indicating mild depression, 19 - 29 indicating moderate depression, and 30 - 63 indicating severe depression (18). The psychometric properties of this questionnaire were evaluated by Toosi et al. in Iran (19).

3.6. Intervention

The chamomile and placebo capsules were purchased from Adonis Gol Daru, Iran. The medications were kept in identical containers. Participants received chamomile or placebo (500 mg) twice a day for eight weeks. This dose was selected according to two previous studies (11-20). Women with mild to moderate depression, as determined by the BDI, were randomized into intervention and control groups. They were requested to complete the demographic and BDI questionnaires before and eight weeks after the intervention.

One of the researchers (ME) was accessible in case participants had any questions during the eight weeks of the intervention. To abide by ethical standards, after the completion of the intervention, participants in the control group were instructed on how to use chamomile if they were interested in using it.

3.7. Statistics

All data were imported into SPSS version 26. The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The chi-square test and independent t-test were used to compare categorical and numerical data between the two groups. For non-parametric variables, the Mann-Whitney U test was used, and the Wilcoxon test was used to compare the frequency of depression between the two groups. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

4. Results

In this study, 144 postpartum women with mild to moderate depression were recruited. Six women in the intervention group and four in the control group withdrew from the study, resulting in 128 women who completed the study. The reasons for dropouts are presented in Figure 1. The mean age of women in the intervention and control groups was 30.50 ± 5.26 years and 31.32 ± 7.05 years, respectively. The mean body mass index of the two groups indicated that women in both groups were overweight. There were no significant differences between the two groups regarding women’s educational attainment, husbands’ educational attainment, economic status, and occupation. Most women in both groups delivered their babies vaginally [intervention: 44 (69.8%); control: 48 (73.8%)] (Table 1).

| Variables | Intervention (N = 63) | Control (N = 65) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 30.50 ± 5.26 | 31.32 ± 7.05 | 0.793 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 30.77 ± 8.62 | 31.81 ± 9.42 | 0.512 |

| Age of husband (y) | 33.85 ± 5.68 | 34.10 ± 7.08 | 0.897 |

| Educational attainment | 0.722 | ||

| Diploma and high school | 14 (22.2) | 18 (27.7) | |

| Associate degree | 37 (58.7) | 37 (56.9) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 12 (19) | 10 (15.4) | |

| Educational attainment of husband | 0.761 | ||

| Diploma and high school | 19 (30.2) | 23 (35.4) | |

| Associate degree | 29 (46) | 26 (40) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 15 (23.8) | 16 (24.6) | |

| Occupation | 0.922 | ||

| Housewife | 48 (76.2) | 50 (76.9) | |

| Employed | 15 (23.8) | 15 (23.1) | |

| Do your income cover your expenses | 0.226 | ||

| No | 23 (36.5) | 29 (44.6) | |

| Somehow | 29 (46) | 31 (47.7) | |

| Yes | 11 (17.5) | 5 (7.7) | |

| Was your pregnancy intended? | 0.614 | ||

| Yes | 58 (92.1) | 61 (93.8) | |

| No | 5 (7.9) | 4 (6.2) | |

| Mode of delivery | 0.614 | ||

| Normal vaginal delivery | 44 (69.8) | 48 (73.8) | |

| Cesarean | 19 (30.2) | 17 (26.2) |

Demographic and Obstetrics Characteristics of the Participants in Intervention and Control Groups a

Table 2 shows the comparison of the mean depression scores and their frequency before and after the intervention. The mean depression score in the intervention group was 21.66 ± 4.01 at baseline, which reduced to 18 ± 3.66 after the intervention. In the control group, the depression scores decreased from 22.36 ± 3.83 at baseline to 20.09 ± 3.77 after the intervention. The within-group differences were significant in both groups (P < 0.0001). The reduction in depression score was statistically significant in the intervention group compared to the control group (P = 0.002).

Before the intervention, 41 (65.1%) women in the intervention group and 50 (76.9%) women in the control group had moderate depression. After the intervention, 7 (11.1%) women in the intervention group were without depression, and 60.3% had mild depression, while the reduction was negligible in the control group (P = 0.002).

| Variables | Intervention (N = 63) | Control (N = 65) | P-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression score before intervention | 21.66 ± 4.01 | 22.36 ± 3.83 | 0.253 |

| Depression score after intervention | 18 ± 3.66 | 20.09 ± 3.77 | 0.002 |

| P-Value c | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | |

| Before intervention | P-Value | ||

| No depression | 0 | 0 | 0.139 c |

| Mild depression | 22 (34.9) | 15 (23.1) | |

| Moderate depression | 41 (65.1) | 50 (76.9) | |

| After intervention | 0.002 | ||

| No depression | 7 (11.1) | 2 (3.1) | |

| Mild depression | 38 (60.3) | 25 (38.5) | |

| Moderate depression | 18 (28.6) | 38 (58.5) |

Comparison of Mean Score and Frequency of Depression in the Intervention and Control Groups a

5. Discussion

This study was designed to evaluate the effect of chamomile on PPD. The pathogenesis of depression mostly relies on the reduction of serotonin and tryptophan, which can induce depressive symptoms (21). In postpartum women, the rapid reduction of estrogen and progesterone hormones after birth is considered an etiology of PPD. These hormones play an important role in preserving emotion, arousal, condition, and motivation (22).

The results of the present study showed that chamomile could significantly reduce the mean score and frequency of PPD. The mechanism by which chamomile reduces depression may result from its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities, modulated by macrophages and CD4 T cells. Therefore, the immune response of people with depression may improve after the consumption of its extract or oil (23). In a study on rats, Juhas et al. found that dietary supplementation of 5000 ppm of chamomile not only significantly reduced edema and weight in the animals but also had protective effects on colonic mucosa and signs of Trinitrobenzene Sulfonic Acid (TNBS)-induced colonic inflammation (24).

Despite a few studies evaluating the effect of chamomile on anxiety and depression in general (11), there is a paucity of research specifically assessing its effect on PPD. The only similar study we found was conducted by Chang and Chen with the participation of 80 postpartum women suffering from poor sleep quality. These women were assigned to a chamomile tea group (for two weeks) and a control group. Sleep quality and symptoms of depression improved significantly in the intervention group, although these effects were immediate and did not last after the post-test. Our results are consistent with those of Chang and Chen, except we used chamomile capsules (500 mg twice a day for eight weeks), which may have improved the efficacy of the intervention.

In another study conducted on 120 patients with depressive disorders, Ahmad et al. found that using a herbal tea including chamomile (20 mg) and saffron (1 mg) twice a day for four weeks significantly improved patient health and depression scores, and reduced inflammatory markers such as C-Reactive Protein (CRP) and Tryptophan (TRP) in the plasma, resulting in an increase of TRP in the brain (21). Although this study was not on postpartum women, it supports our findings.

Heidari-Fard et al. found that chamomile aromatherapy during labor significantly increased satisfaction with birth but was not effective regarding uterus contractions (25). Amsterdam et al. studied 57 participants with co-morbid anxiety and depression and found that chamomile significantly reduced depression scores, with a non-significant reduction in participants who had anxiety and co-morbid depression (26).

Bazrafshan et al. compared the effect of 2 g of lavender with chamomile on anxiety and depression in postmenopausal women. Their results showed that both herbs significantly reduced anxiety and depression scores (13). Our results are consistent with the findings of Amsterdam et al. and Bazrafshan et al. (13, 26).

5.1. Limitations

Despite its merits, this study has some limitations. First, the women were recruited from four public health centers in Dezful, Iran, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, we recruited women with mild and moderate PPD; therefore, the effect of chamomile on severe PPD remains to be evaluated in future studies. Third, participants in the intervention group consumed chamomile for eight weeks and were then assessed for depression. We are uncertain about the durability of the drug's effects beyond eight weeks. Further studies with longer follow-up periods are recommended to shed more light on this issue.

5.2. Conclusions

The results of the present study showed that chamomile capsules (500 mg) consumed twice a day for eight weeks significantly reduced the score and frequency of mild and moderate PPD. Due to the lack of laboratory evaluation, these results should be interpreted with caution, and further studies are needed to confirm these findings.