1. Background

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) represent chronic, relapsing conditions affecting the lower gastrointestinal tract, encompassing disorders such as Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) (1). In UC, inflammatory lesions may manifest in any segment of the colon, initiating with mucosal inflammation in the rectum and advancing proximally in a continuous fashion (2). Currently, the pharmacotherapy of UC aims to induce and maintain remission of symptoms, reduce the risk of complications, and enhance the quality of life (QoL) as the primary objective. Unfortunately, the incidence of UC is increasing globally, and the pharmacological agents used in its management can cause numerous adverse drug reactions (ADRs) in a substantial number of patients (3). Moreover, it has been reported that over 15% of UC patients may require more aggressive interventions, such as surgery, due to the failure of medication (4).

Due to the inadequate response to conventional pharmacotherapy, the occurrence of ADRs, and a desire for greater control over their condition, a significant proportion of patients with UC resort to complementary and herbal medicine more frequently than the general population. In a meta-analysis, Iyengar et al. investigated the effects of 18 herbal medicines on clinical and endoscopic responses in UC patients (5). Among the evaluated herbal treatments, they concluded that Curcuma longa was associated with a significantly higher rate of clinical remission and relief of colonic lesions in UC patients (5). In a clinical study, the effects of Chios mastic gum, derived from the tree Pistacia lentiscus var. Chia, have been evaluated on symptoms of IBD. Their findings indicate that the clinical data regarding the resin’s effects on IBD are highly insufficient. Despite the existence of only three limited clinical trials examining the resin’s impact on patients with UC and CD, notable clinical and paraclinical responses have been observed (6).

The genus Pistacia has been extensively highlighted in traditional medicine for its therapeutic effects on gastrointestinal disorders. A comprehensive review of recent studies examining the impact of the Pistacia genus on gastrointestinal diseases has been published in 2024. The majority of the data up to 2022 pertains to its protective effects against IBD and peptic ulcers (7). It appears that α-pinene, a terpenoid found in the Pistacia genus, plays a significant role in inhibiting IL-1β-stimulated inflammatory pathways (8).

Previous studies on the effects of mastic gum (derived from Pistacia species) on IBD have been limited and contain incomplete data. The comprehensive impact of α-pinene, the principal component of mastic gum, has not been previously assessed. Additionally, prior research has predominantly focused on some inflammatory markers in patients with UC.

2. Objectives

The objective of the current clinical trial is to evaluate the efficacy and safety of α-pinene capsule administration (derived from Pistacia kurdica) as an adjuvant therapy for alleviating symptoms of UC and improving patients’ QoL (primary outcomes). The secondary outcome involves assessing the impact of α-pinene on optimizing laboratory markers in UC patients.

3. Methods

3.1. Trial Design

A randomized double-blind clinical study was designed to be conducted in the gastroenterology clinic of Imam Hossein Hospital, Tehran, Iran. The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pharmacy, Nursing, and Midwifery Schools affiliated with Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1403.024). The trial was registered in the Iranian Clinical Trial Registry with the number IRCT20121021011192N17. Following a comprehensive explanation of the trial’s aim to the participants, informed written consent was obtained, and they were considered for enrollment in the trial.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria comprised individuals aged 20 years and older who had been diagnosed with mild to moderate UC. This diagnosis was established based on a combination of clinical signs and symptoms, laboratory tests, and procedures such as endoscopy and radiologic imaging (9). Exclusion criteria included patients with a history of allergy to herbal medicine, seizure, psychiatric disorders, cirrhosis (Child-Pugh B or C), renal failure (creatinine clearance below 30 mL/min), and pregnant or lactating women.

3.3. Intervention, Outcomes and Follow-up

Baseline assessment of clinical activity was conducted in the participants using the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index Questionnaire (SCCAIQ). It consists of six questions in the areas of bowel frequency, urgency of defecation, blood in stool, general well-being, and extra-colonic symptoms. It is a reliable tool for the clinical evaluation of UC patients (4). Additionally, the Crohn’s and UC Questionnaire-8 (CUCQ-8) was completed through interviews with participants at baseline. The CUCQ-8 is a concise and well-structured tool for assessing the QoL in patients with IBD (10).

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were determined in all participants before entering the trial. Participants were assigned randomization numbers and treated in accordance with the study protocol. All patients received 5-aminosalicylates, with or without azathioprine, as the standard pharmacologic agents for the maintenance therapy of UC. Randomization was conducted using an online statistical computing web program (http://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/randomize1.cfm). Participants were enrolled and randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either α-pinene (0.2 g/day) or an identical placebo. The α-pinene capsules utilized in this trial were procured from Jiran Darou, Sanandaj, Iran. Placebo capsules were also prepared by the same company. The α-pinene capsules were derived from P. kurdica, with each capsule containing 200 mg of α-pinene. There is currently no data available on the effective dose of α-pinene for UC. However, a recent trial demonstrated a positive effect of α-pinene at a dose of 0.2 g/day in functional dyspepsia, with no serious adverse reactions reported (11). Therefore, we opted to use the same dosage. Participants were instructed to take either the active capsule or the placebo for a duration of two months and to refrain from using any herbal medications during the study period due to the potential presence of α-pinene.

After a period of two months, the clinical activity was reassessed using the SCCAIQ and the CUCQ-8. Additionally, ESR and CRP levels were measured at the conclusion of the second month as laboratory parameters. In the event of any serious adverse effects related to the use of α-pinene or placebo, the patient was instructed to discontinue the α-pinene or placebo, resulting in their exclusion from the trial. Patient adherence was monitored throughout the trial via telephone contact. According to the standard definition of adherence, patients who did not consume at least 80% of the α-pinene or placebo were also excluded from the trial (12).

3.4. Statistical Analysis and Sample Size Calculation

All data were analyzed using the statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) version 11.5, with P-values greater than 0.05 considered non-significant. The means of age, Body Mass Index (BMI), duration of UC, SCCAIQ score, items of CUCQ-8, ESR, and CRP were compared within groups using the t-test for normally distributed data or the Mann-Whitney test for non-normally distributed data. For the comparison of categorical variables, including sex distribution and differences in medication use between the two groups, the chi-square test was employed. The required sample size calculations for the trials were adapted from the study by Mohammadi et al. (13). To achieve SCCAIQ scores of 0.8 and 2 in the α-pinene and placebo arms, respectively, after two months, considering a standard deviation of 1.5, an alpha of 0.05, and a beta of 80%, a minimum of 28 patients were required in each arm.

4. Results

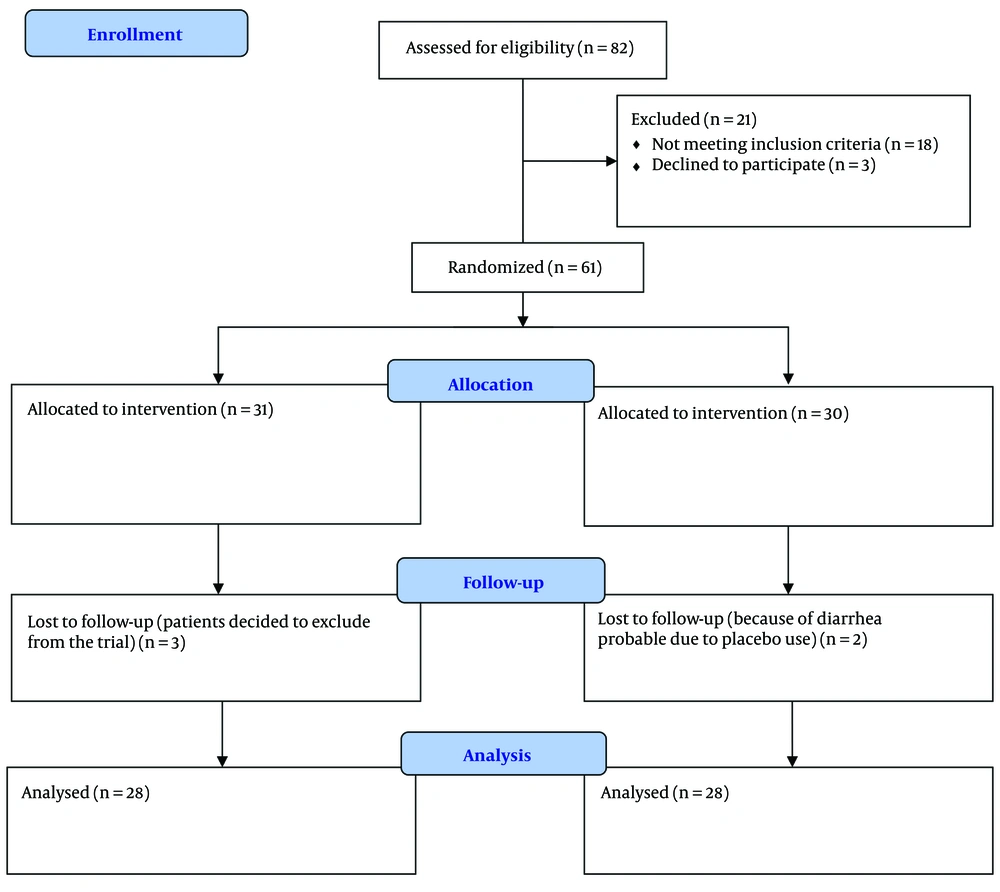

Between June 2024 and November 2024, a total of 82 patients with a diagnosis of mild to moderate UC were screened for the present trial. Finally, 56 patients completed the trial correctly. The flowchart of patients throughout the trial is shown in Figure 1. Demographic data and SCCAIQ scores of participants at baseline are shown in Table 1. At baseline, there were no significant differences between the two arms regarding mean age, sex, BMI, duration of UC, medication for treatment of UC, and SCCAIQ score. After a two-month period, the SCCAIQ scores were determined to be 2.9 ± 1.5 in the α-pinene group and 4.9 ± 2.9 in the placebo group. Statistical analysis revealed that the lower SCCAIQ scores observed in the α-pinene group, compared to the placebo group, were significant (P = 0.02). Table 2 presents the items of the CUCQ-8 for both groups before and after the intervention. Prior to the intervention, there were no significant differences between the two groups regarding the various items of the CUCQ-8. However, post-intervention, the α-pinene group showed significant improvements compared to the placebo group in the number of days participants felt tired, generally unwell, experienced abdominal pain, and had to rush to the toilet (P = 0.04, P = 0.04, P = 0.02, and P = 0.02, respectively).

| Variables | α -pinene Arm (n = 28) | Placebo Arm (n = 28) | P-Value | Total (n = 56) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | 20 (71.4) | 19 (67.8) | 0.86 | 39 (69.6) |

| Mean age (y) | 28.0 ± 6.3 | 30.2 ± 5.4 | 0.57 | 29.2 ± 6.1 |

| BMI | 23.4 ± 1.5 | 24.2 ± 1.6 | 0.89 | 23.8 ± 1.5 |

| UC medications | 0.68 | |||

| Aminosalicylates | 18 | 16 | 34 | |

| Aminosalicylates plus azathioprine | 10 | 12 | 22 | |

| Duration of UC (y) | 4.0 ± 1.5 | 3.1 ± 1.9 | 0.43 | 3.6 ± 1.7 |

| Primary SCCAIQ score | 5.4 ± 2.0 | 5.8 ± 2.3 | 0.39 | 5.6 ± 2.1 |

Abbreviations: UC, ulcerative colitis; SCCAIQ, Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index Questionnaire; BMI, Body Mass Index.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

| Items | α-pinene Group (n = 28) | Control Group (n = 28) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Days felt tired | |||

| Before intervention | 4.3 ± 2.3 | 4.2 ± 2.1 | 0.08 |

| After intervention | 3.1 ± 2.0 | 4.3 ± 2.5 | 0.04 |

| Prevented from going out socially by bowel condition (not at all) | |||

| Before intervention | 14 (50) | 12 (42.8) | 0.65 |

| After intervention | 14 (50) | 13 (46.4) | 0.78 |

| Days felt generally unwell | |||

| Before intervention | 4.3 ± 2.3 | 4.2 ± 2.1 | 0.18 |

| After intervention | 3.1 ± 2.0 | 4.3 ± 2.5 | 0.04 |

| Days felt pain in abdomen | |||

| Before intervention | 1.5 ± 3.2 | 1.3 ± 2.3 | 0.35 |

| After intervention | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 1.2 ± 2.1 | 0.02 |

| Nights getting up to use a toilet | |||

| Before intervention | 2.4 ± 1.1 | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 0.39 |

| After intervention | 2.3 ± 2.1 | 2.5 ± 1.9 | 0.67 |

| Days felt bloated | |||

| Before intervention | 2.0 ± 3.4 | 2.5 ± 3.9 | 0.56 |

| After intervention | 2.0 ± 3.4 | 2.4 ± 3.8 | 0.24 |

| Feeing upset (not at all) | |||

| Before intervention | 14 (50) | 12 (42.8) | 0.65 |

| After intervention | 14 (50) | 13 (46.4) | 0.78 |

| Days had to rush to the toilet | |||

| Before intervention | 2.3 ± 4.4 | 2.1 ± 3.3 | 0.89 |

| After intervention | 1.0 ± 1.2 | 2.2 ± 3.1 | 0.02 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

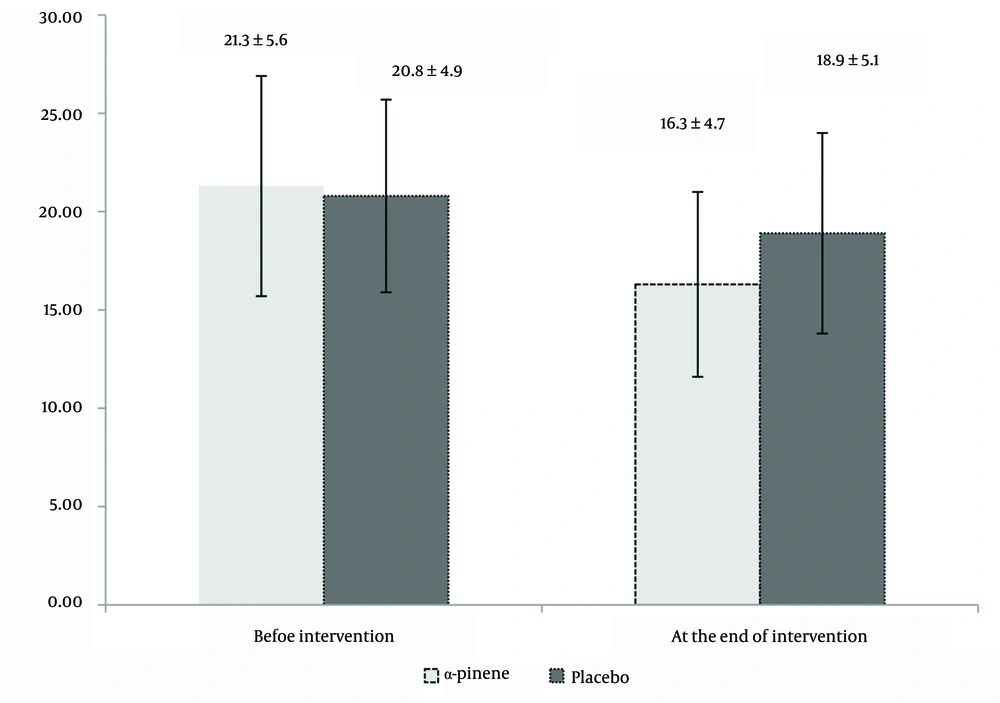

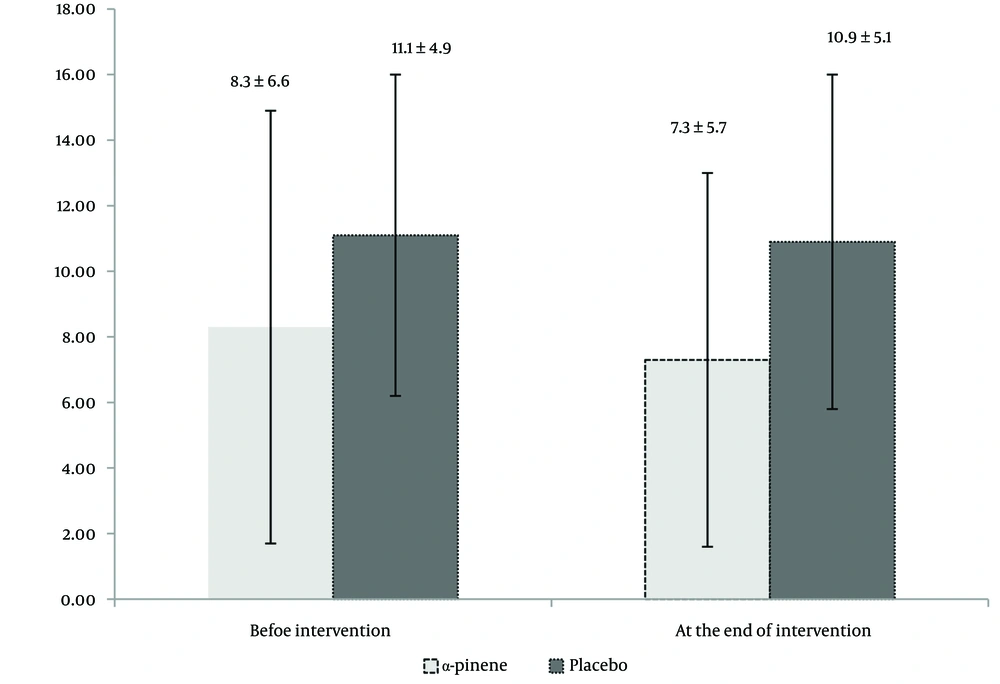

In Figures 2 and 3, the levels of ESR and CRP are presented at the beginning and conclusion of the trial for both groups. There were no significant differences in ESR and CRP levels between the two groups prior to the trial (P = 0.87 and P = 0.69, respectively). After two months, both CRP and ESR levels showed a significant decrease compared to baseline values (P = 0.03 and P = 0.04, respectively). However, by the end of the intervention, there were no significant differences in ESR and CRP levels between the two groups (P = 0.64 and P = 0.78, respectively). No patient missed more than 10% of their doses of either α-pinene or placebo during the trial. In terms of tolerability, one patient in the α-pinene group reported experiencing nightmares on the first and second nights of α-pinene administration, which subsequently resolved and did not necessitate discontinuation of the treatment. Additionally, two patients in the placebo group reported mild headaches on the first day of placebo administration. Overall, participants tolerated both α-pinene and placebo well, with no dropouts from the trial due to ADRs.

5. Discussion

α-pinene, a prominent monoterpene found in various plants, including those of the genus Pistacia, exhibits a wide range of pharmacological properties. It has been documented to exhibit a range of pharmacological properties, including the neutralization of antibiotic resistance, anticoagulant activity, antitumor effects, antioxidant capacity, anti-inflammatory properties, and analgesic effects (8). The anti-inflammatory property of α-pinene could be helpful in the management of chronic inflammatory diseases such as UC (6). IL-1β is a critical mediator of inflammation and tissue damage in UC. Given its pivotal role in promoting inflammation and immune responses in UC, targeting IL-1β or its receptors represents a promising therapeutic strategy (14). In an animal model, biochemical evaluations revealed that the administration of α-pinene significantly moderated the elevation of IL-1β in the spinal cord induced by formalin injection (15). Numerous animal studies have investigated the effects of herbal medicines containing α-pinene on the alleviation of UC models (16, 17). However, there is a paucity of clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of α-pinene as an adjunctive treatment for UC. To the best of our knowledge, our trial is the first to evaluate the net effect of α-pinene administration as an adjuvant therapy for UC patients. It is worth noting that the main constituent of mastic gum oil is α-pinene (79%) (18).

In previous clinical trials, mastic gum (derived from P. lentiscus) consisting of α-pinene has been evaluated. For example, in a randomized, double-blind clinical study, investigators evaluated the effects of P. lentiscus, a rich source of α-pinene, on oxidative stress biomarkers in patients diagnosed with IBD. The study included 20 patients with UC and 40 patients with CD. In addition to the standard IBD therapy, the intervention group received 2.8 g/day of mastic gum for a duration of three months. The results indicated that the intervention led to favorable changes in oxidative stress biomarkers, including plasma oxidized low-density lipoprotein and total serum oxidizability, in IBD patients. However, the trial did not include any clinical outcomes for patient follow-up (19).

In another study, 68 patients with IBD were randomly assigned to receive either mastic gum (2.8 g/day) or a placebo, in addition to their standard treatment regimen. The study assessed IBD activity using a questionnaire, as well as biochemical markers and fecal calprotectin levels. The results indicated no significant differences in the changes of inflammatory markers between the two groups. Notably, increases in serum interleukin-6 and fecal calprotectin were observed only in the placebo group.

Furthermore, disease activity indices did not show significant changes at follow-up in either group (20). In contrast to the aforementioned trial, our study observed a significant clinical response in UC patients treated with α-pinene compared to those receiving a placebo, as measured by the SCCAIQ, a recognized indicator for the clinical assessment of IBD patients. Consistent with the findings of the mentioned study (21), no changes were detected in the inflammatory biomarkers (ESR and CRP) among the participants evaluated. It is noteworthy that, unlike fecal calprotectin, both ESR and CRP are non-specific markers for monitoring the severity of UC alone (22). Recent studies have demonstrated that the assessment of fecal calprotectin is more sensitive and specific than ESR or CRP in estimating the severity of UC (4). Due to budgetary constraints, fecal calprotectin was not assayed in the current trial.

Previous clinical trials have not evaluated the QoL in patients who received a herbal compound containing α-pinene. There was no significant difference in the subdivision of CUCQ-8 between the two groups at baseline. After two months, the α-pinene group showed a greater reduction in the scores for days feeling tired, days feeling generally unwell, days experiencing abdominal pain, and days needing to rush to the toilet. Statistical analysis indicated that these differences were significant (P = 0.04, 0.04, 0.02, 0.02, respectively). Assessing the QoL in patients with UC is of paramount importance. Previous clinical trials investigating the effects of mastic gum on IBD have not included data on QoL before and after the intervention. These studies primarily concentrated on biochemical markers, with clinical indicators being a secondary focus (19, 20, 22). In the current trial, we simultaneously evaluated clinical outcomes, inflammatory markers, and QoL in the patients. The SCCAIQ was utilized to assess the clinical outcomes of the participants, revealing a significant response in the α-pinene group compared to the placebo group after two months. It is important to note that there was no difference in the pharmacotherapy regimen of the UC patients between the α-pinene and placebo groups during the study period (P = 0.02).

In 1989, a questionnaire was developed for the clinical assessment of IBD patients for the first time (23). Although several questionnaires for UC activity have been developed in previous years, there is no gold standard among them (24). Since SCCAIQ, compared with many others, is a purely clinical questionnaire for UC assessment (23), we preferred to use SCCAIQ as a tool for clinical assessment in the present trial. In future studies, we propose the assessment of fecal calprotectin as a significant biomarker for UC to investigate potential differences between groups. Given that the inhibition of IL-1β is likely the mechanism by which α-pinene alleviates UC symptoms, it is highly recommended that future clinical trials evaluate this biomarker. Additionally, given the safety profile of α-pinene, we recommend evaluating its effects at higher doses. Our study was constrained to a dosage of 0.2 g/day of α-pinene, and it is plausible that this dosage is insufficient to elicit a positive response on inflammatory biomarkers. Considering the favorable safety profile of α-pinene, we advocate for the assessment of its effects at higher dosages.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of our study indicate that adjuvant α-pinene therapy at a dosage of 0.2 g/day over a two-month period is relatively safe. Furthermore, it may contribute to the amelioration of clinical signs and symptoms, as well as the enhancement of QoL in patients with UC.