1. Context

The prenyloxy coumarins are a class of secondary metabolites with promising pharmacological activities. These compounds comprise structures in which a prenyl side chain is linked to the coumarin scaffold through an ethereal bond. In a type of prenyloxy coumarins, the prenyl side chain is an isopentenyl moiety (1) or, in other words, a hemiterpene moiety (C5) (2). Although a hemiterpene is an isoprene group, several five-carbon compounds containing an isopentane skeleton, which can be saturated, unsaturated, repeatedly oxygenated, or methoxylated, are known as hemiterpenes (3). Szabo et al. first used the term “Coumarin-Hemiterpene Ethers” in 1985 for coumarins bearing a hemiterpene moiety by a C-O linkage (4). To date, numerous natural coumarin-hemiterpene ethers (NCHEs) have been reported with various biological activities such as antioxidant (5, 6), anti-inflammatory (7-9), antiviral (10, 11), antifungal (12, 13), cytotoxic, apoptotic (14), and antimutagenic activities (15). There are also reports on the synthesis and biological evaluation of coumarin-hemiterpene ethers (CHEs) that have not been found in nature (16). Although most NCHEs are aglycones, a limited number of glycosylated NCHEs have also been documented (17, 18). However, a comprehensive report on NCHEs and their plant sources has not been available. Additionally, the significance of NCHEs as chemotaxonomic markers has not been thoroughly investigated or discussed.

For the first time, in this review, we have categorized NCHEs based on their structural features and plant sources and have introduced their chemotaxonomic potential.

2. Evidence Acquisition

Electronic databases, including PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, Google Scholar, and ScienceDirect, were searched for isolation reports of NCHEs. All relevant papers published up to February 2025 were collected. Relevant articles written in English or those that had at least an English abstract were included in this study. Studies involving synthetic CHEs and CHEs isolated from non-plant sources were excluded from the current study. The search terms were as follows: Hemiterpene, isopentenyloxy, prenyloxy, oxy prenyl, dimethyl allyloxy, methyl butoxy, methyl butyloxy, isoprene, and coumarin.

3. Results

3.1. Coumarin-Hemiterpene Ethers and Their Plant Sources

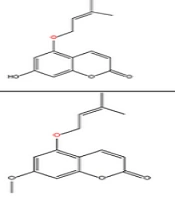

As previously mentioned, only a few glycosylated NCHEs, such as 4'-O-(β-D-glucopyranosyl) desoxylacarol and 5-O-(β-D-glucopyranosyl) lacarol from the aerial parts of Artemisia armeniaca (Asteraceae) (17), and 6-O-[β-D-apiofuranosyl-(1-6)-β-D-glucopyranosyl]-prenyletin from the roots of Prangos uloptera (Apiaceae) (18), have been reported to date. The structures of these glycosylated NCHEs are illustrated in Figure 1.

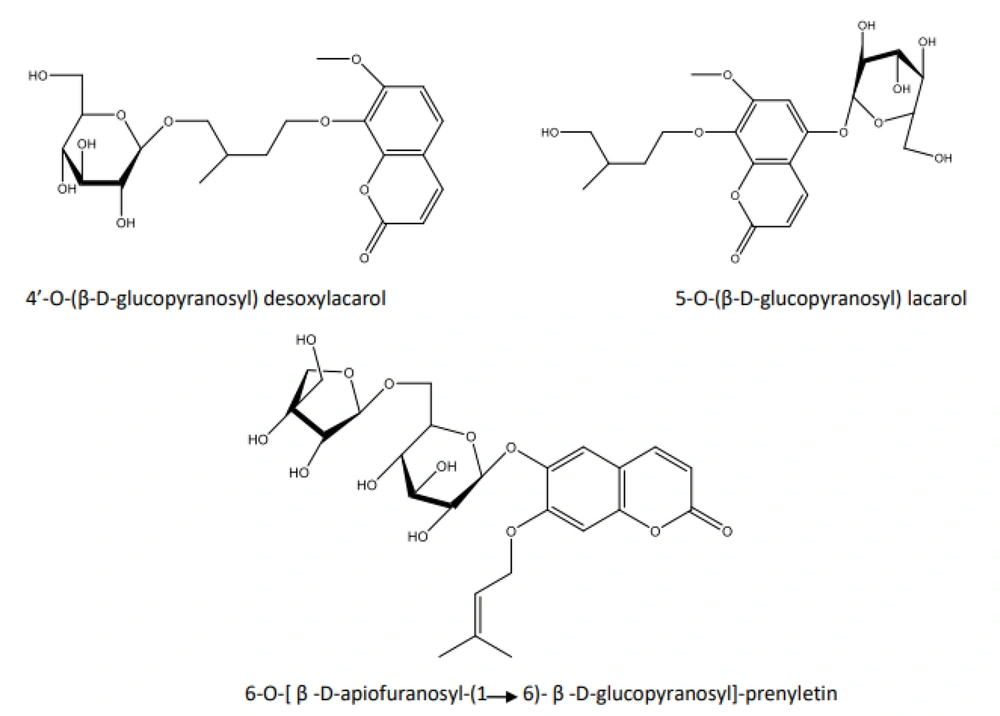

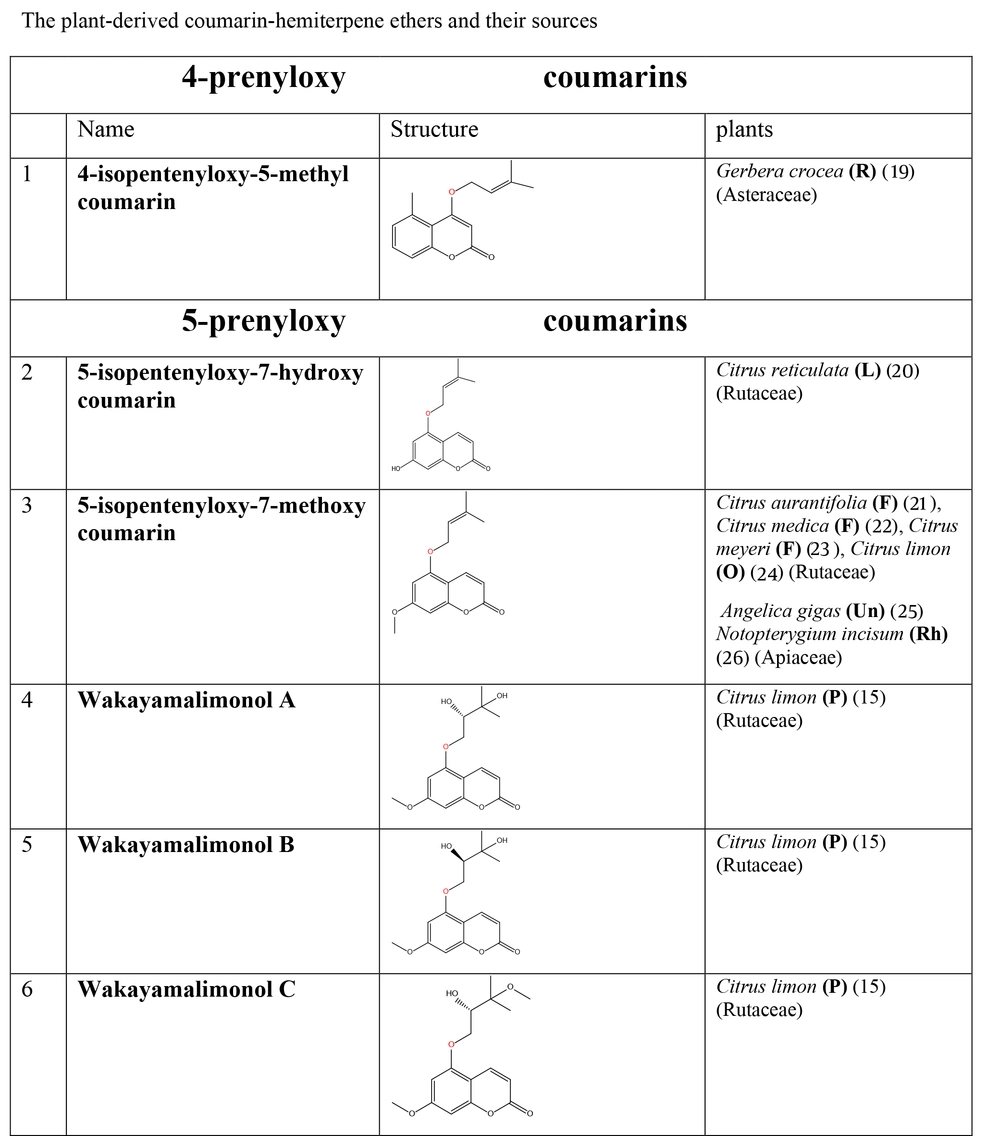

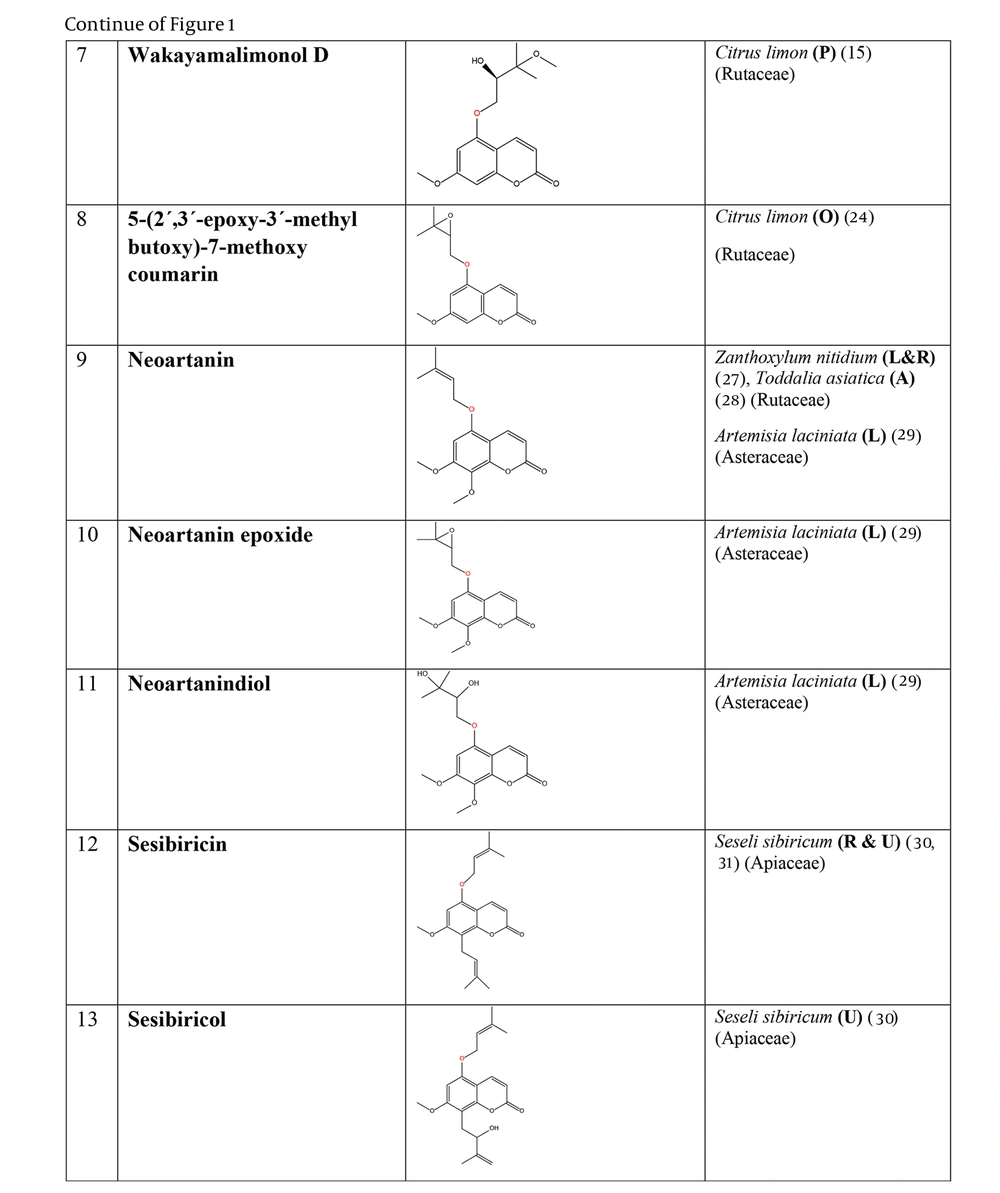

The non-glycosylated NCHEs are found in 15 plant families, including Rutaceae, Asteraceae, Apiaceae, Cucurbitaceae, Amaranthaceae, Myrtaceae, Campanulaceae, Solanaceae, Polygalaceae, Convolvulaceae, Simaroubaceae, Thymelaeaceae, Theaceae, Scrophulariaceae, and Lamiaceae. Their structures, arranged based on the attachment site of the hemiterpene ether portion to the coumarin scaffold, and plant sources containing CHEs, are depicted and presented in Figure 2.

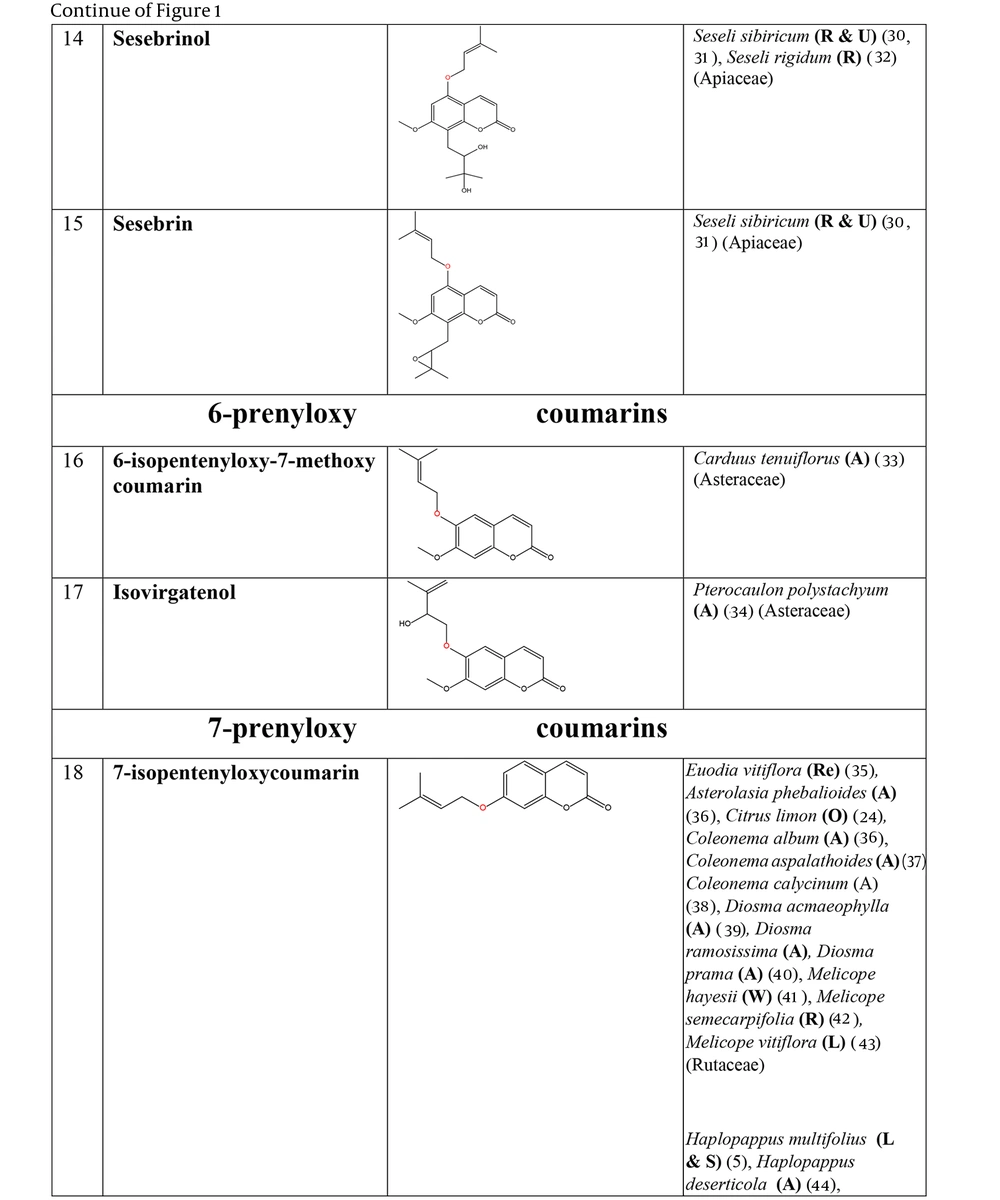

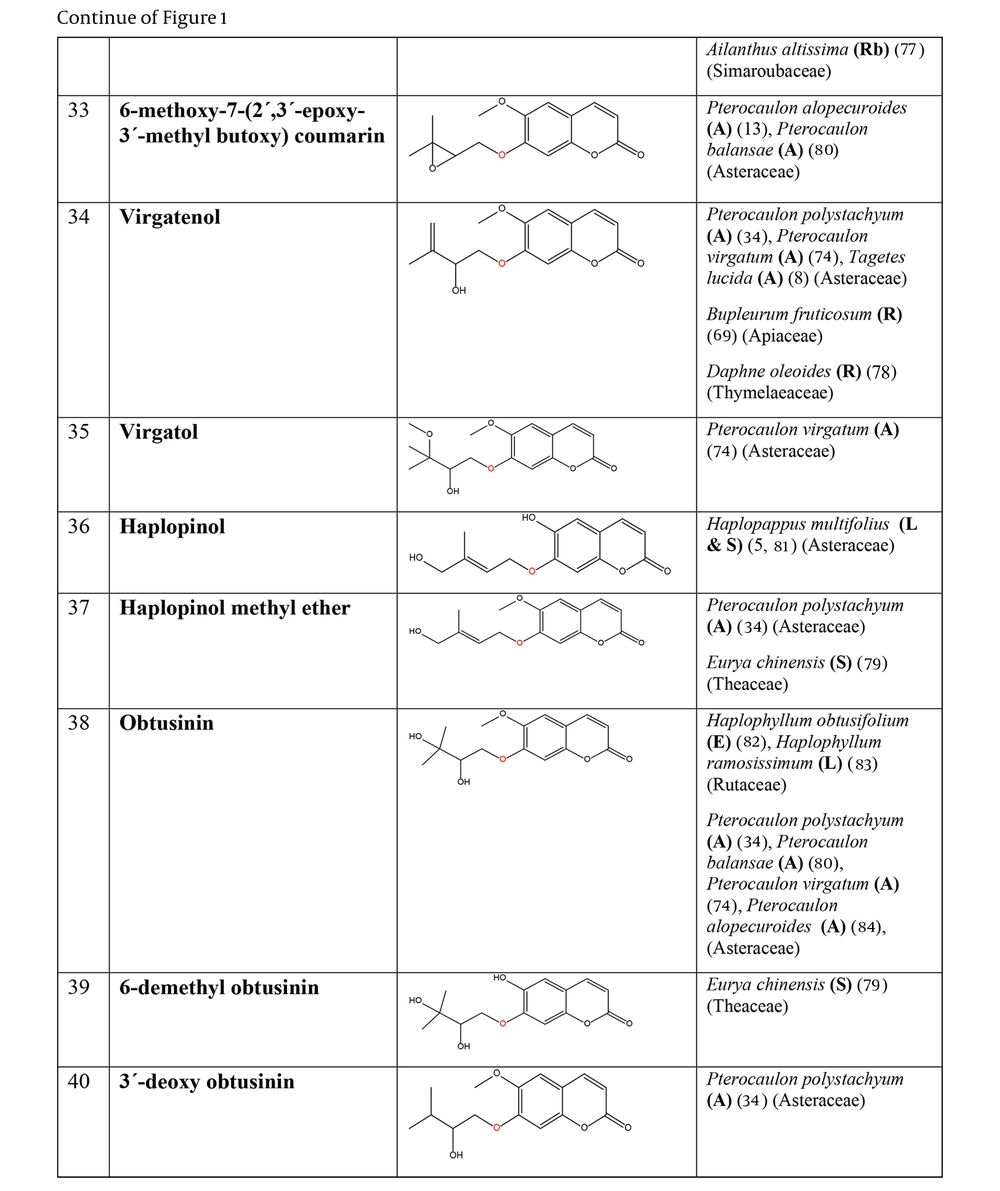

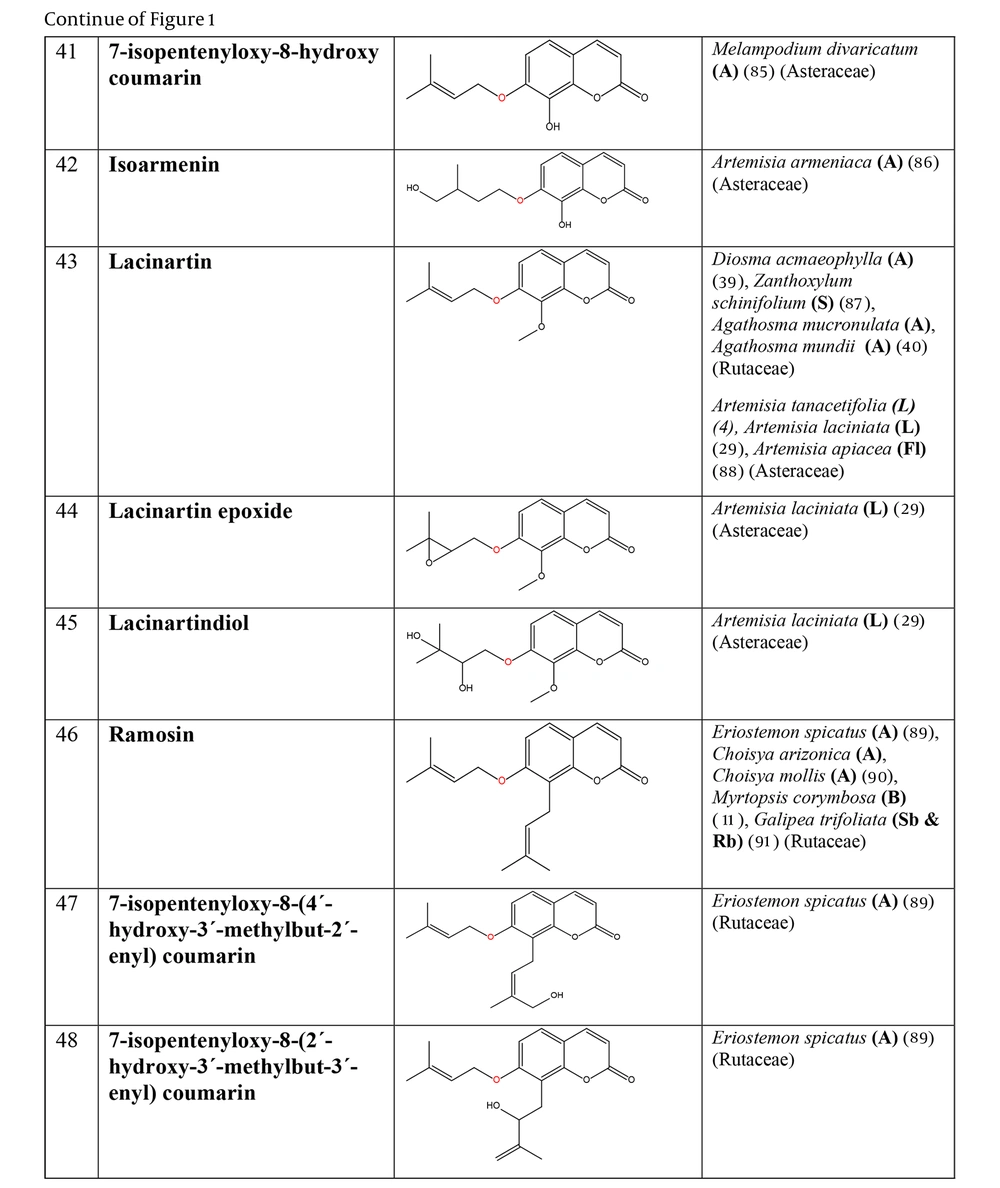

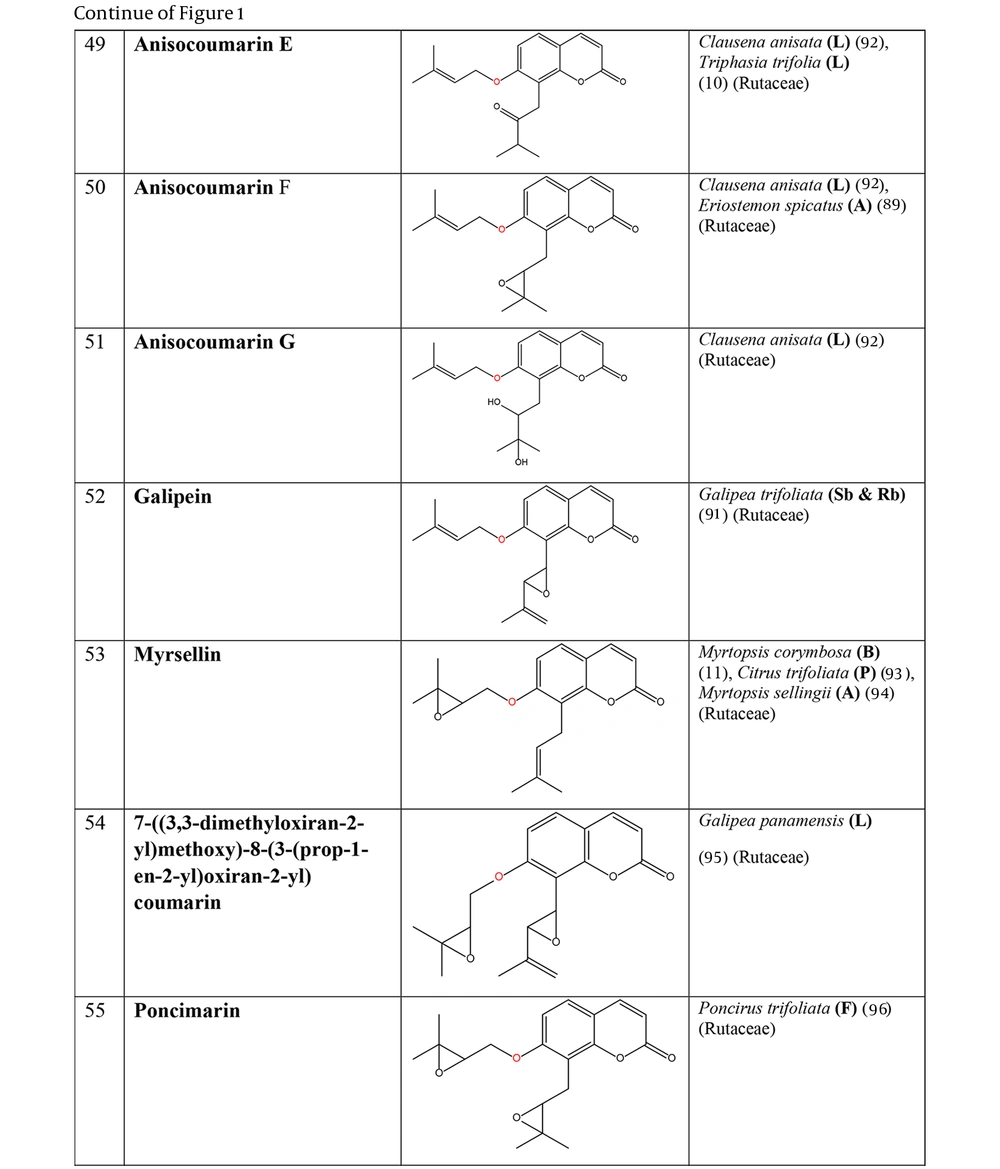

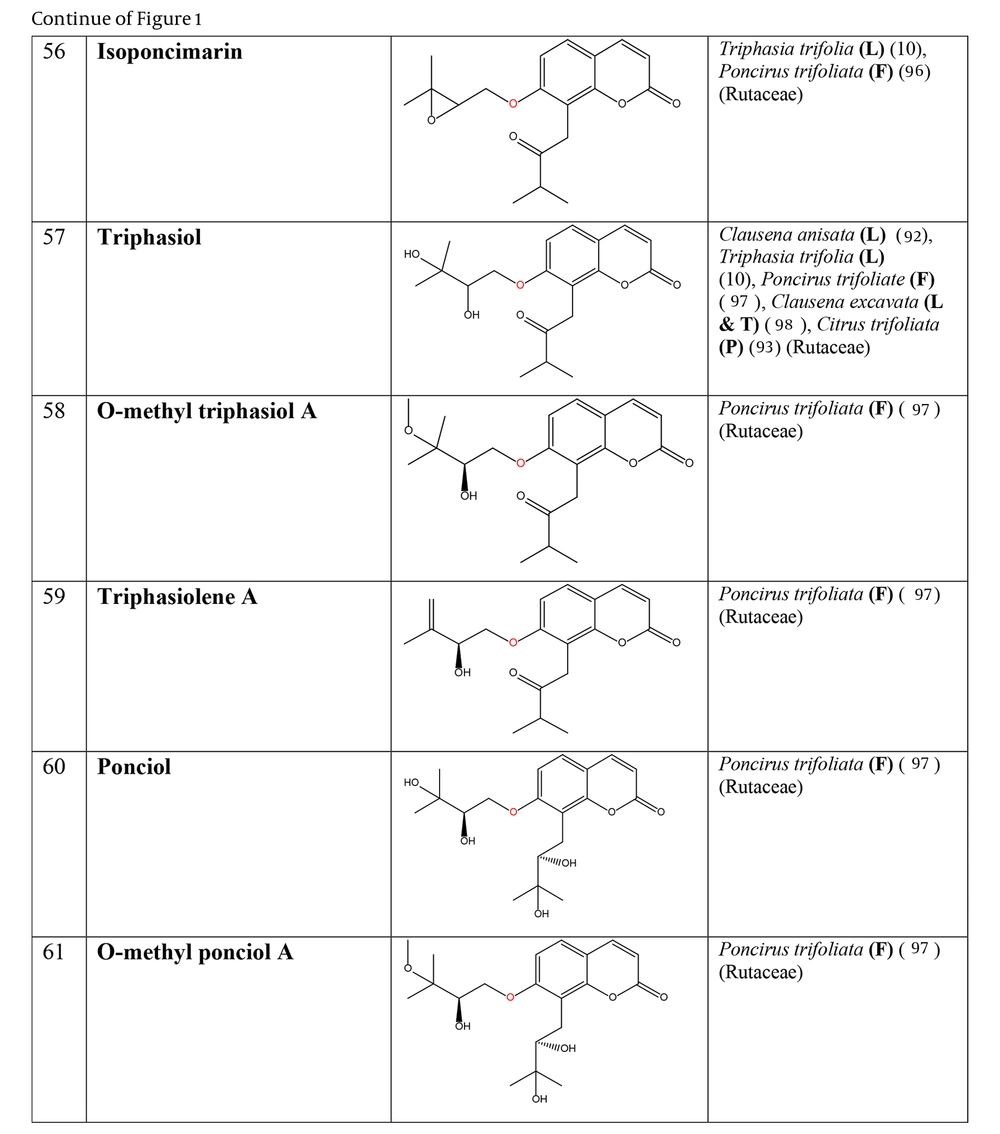

The plant-derived coumarin-hemiterpene ethers (CHEs) and their sources (Abbreviations: A, aerial parts; B, bark; Br, branches; E, epigeal parts; Eo, essential oil; F, fruits; Fl, flowers; L, leaves; O, oil; P, peels; R, root; Rb, root barks; Re, resin; Rh, rhizome; S, stems; Sb, stem bark; Se, seed; T, twigs; U, umbls; Un, underground parts; W, wood; Wh, whole herb) (15, 19-26).

The plant-derived coumarin-hemiterpene ethers (CHEs) and their sources (Abbreviations: A, aerial parts; B, bark; Br, branches; E, epigeal parts; Eo, essential oil; F, fruits; Fl, flowers; L, leaves; O, oil; P, peels; R, root; Rb, root barks; Re, resin; Rh, rhizome; S, stems; Sb, stem bark; Se, seed; T, twigs; U, umbls; Un, underground parts; W, wood; Wh, whole herb) (15, 24, 27-31).

The plant-derived coumarin-hemiterpene ethers (CHEs) and their sources (Abbreviations: A, aerial parts; B, bark; Br, branches; E, epigeal parts; Eo, essential oil; F, fruits; Fl, flowers; L, leaves; O, oil; P, peels; R, root; Rb, root barks; Re, resin; Rh, rhizome; S, stems; Sb, stem bark; Se, seed; T, twigs; U, umbls; Un, underground parts; W, wood; Wh, whole herb) (5, 24, 30-44).

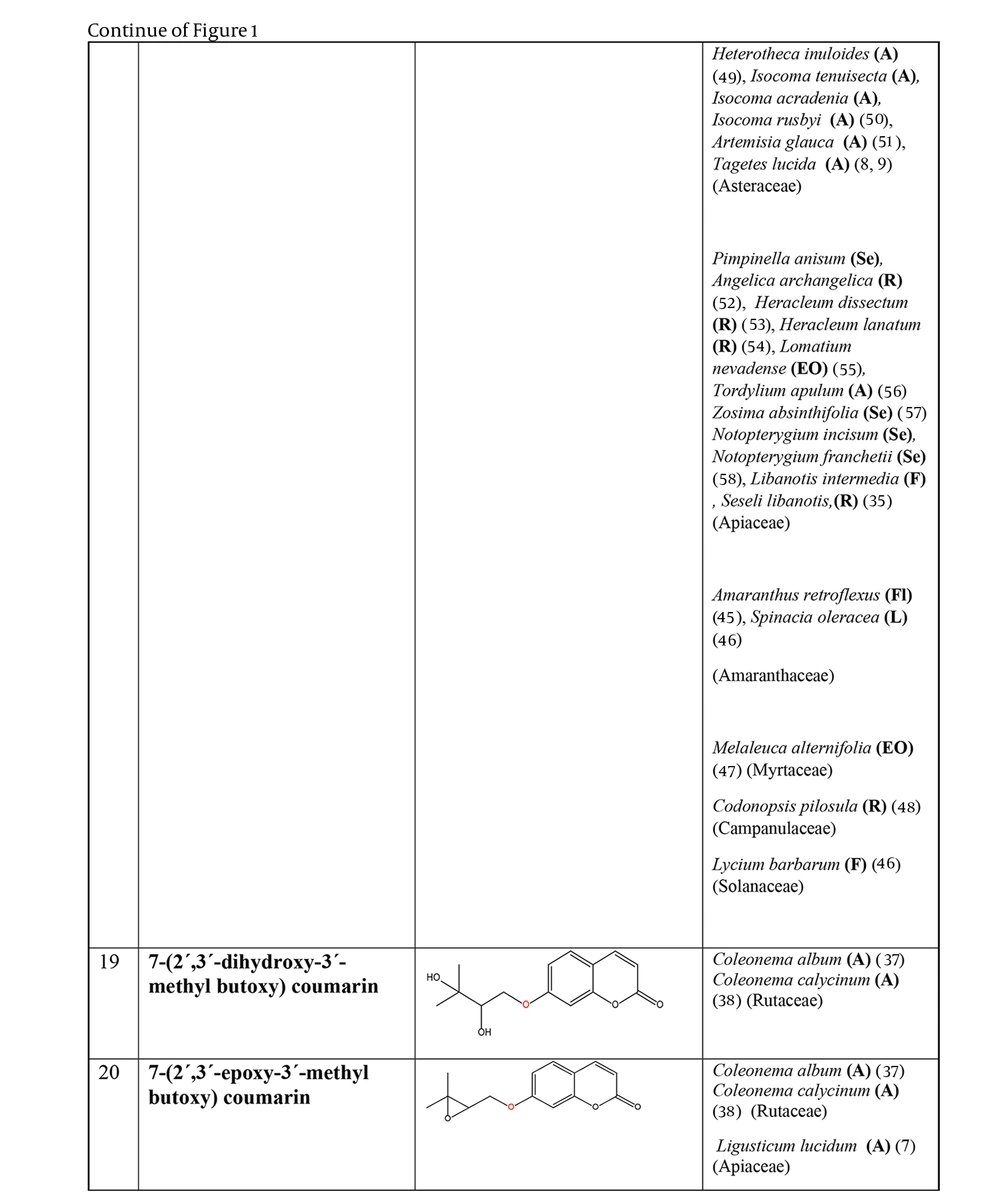

The plant-derived coumarin-hemiterpene ethers (CHEs) and their sources (Abbreviations: A, aerial parts; B, bark; Br, branches; E, epigeal parts; Eo, essential oil; F, fruits; Fl, flowers; L, leaves; O, oil; P, peels; R, root; Rb, root barks; Re, resin; Rh, rhizome; S, stems; Sb, stem bark; Se, seed; T, twigs; U, umbls; Un, underground parts; W, wood; Wh, whole herb) (8, 9, 35, 45-58).

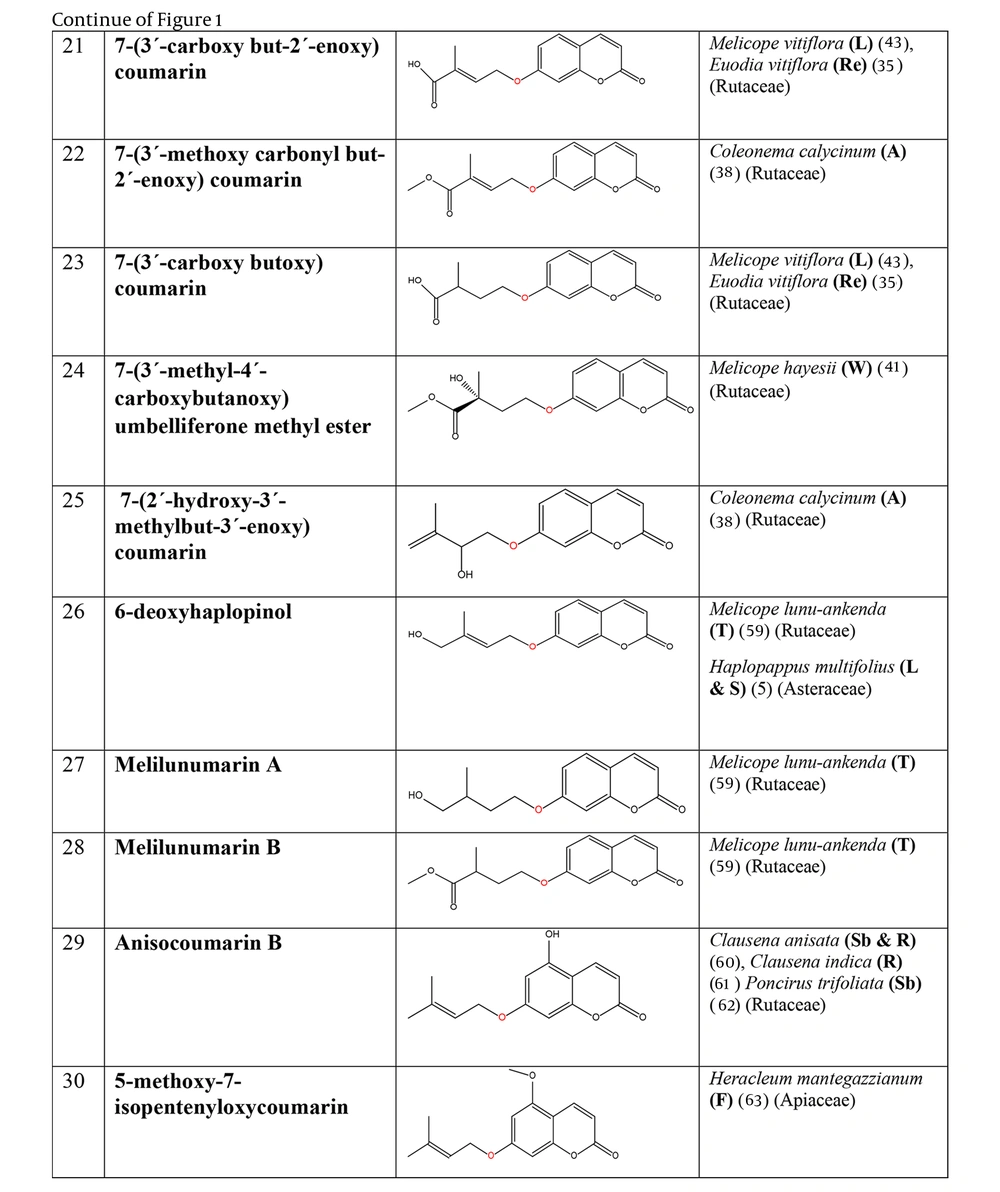

The plant-derived coumarin-hemiterpene ethers (CHEs) and their source (Abbreviations: A, aerial parts; B, bark; Br, branches; E, epigeal parts; Eo, essential oil; F, fruits; Fl, flowers; L, leaves; O, oil; P, peels; R, root; Rb, root barks; Re, resin; Rh, rhizome; S, stems; Sb, stem bark; Se, seed; T, twigs; U, umbls; Un, underground parts; W, wood; Wh, whole herb) (5, 35, 38, 41, 43, 59-63).

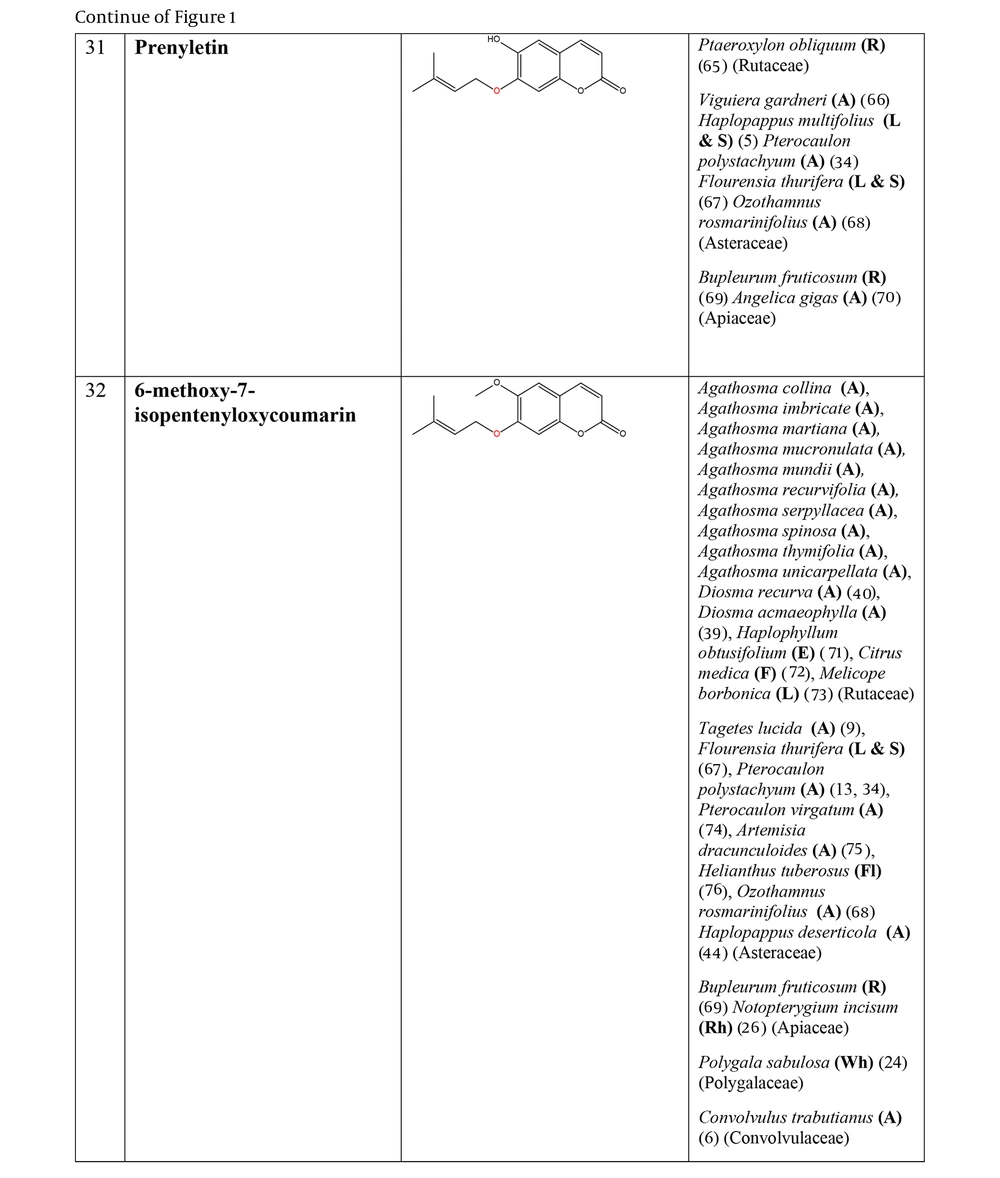

The plant-derived coumarin-hemiterpene ethers (CHEs) and their sources (Abbreviations: A, aerial parts; B, bark; Br, branches; E, epigeal parts; Eo, essential oil; F, fruits; Fl, flowers; L, leaves; O, oil; P, peels; R, root; Rb, root barks; Re, resin; Rh, rhizome; S, stems; Sb, stem bark; Se, seed; T, twigs; U, umbls; Un, underground parts; W, wood; Wh, whole herb) (5, 6, 9, 13, 26, 34, 39, 40, 44, 64-76).

The plant-derived coumarin-hemiterpene ethers (CHEs) and their sources (Abbreviations: A, aerial parts; B, bark; Br, branches; E, epigeal parts; Eo, essential oil; F, fruits; Fl, flowers; L, leaves; O, oil; P, peels; R, root; Rb, root barks; Re, resin; Rh, rhizome; S, stems; Sb, stem bark; Se, seed; T, twigs; U, umbls; Un, underground parts; W, wood; Wh, whole herb) (5, 8, 13, 34, 69, 74, 77-84).

The plant-derived coumarin-hemiterpene ethers (CHEs) and their sources (Abbreviations: A, aerial parts; B, bark; Br, branches; E, epigeal parts; Eo, essential oil; F, fruits; Fl, flowers; L, leaves; O, oil; P, peels; R, root; Rb, root barks; Re, resin; Rh, rhizome; S, stems; Sb, stem bark; Se, seed; T, twigs; U, umbls; Un, underground parts; W, wood; Wh, whole herb) (4, 11, 29, 39, 40, 85-91).

The plant-derived coumarin-hemiterpene ethers (CHEs) and their sources (Abbreviations: A, aerial parts; B, bark; Br, branches; E, epigeal parts; Eo, essential oil; F, fruits; Fl, flowers; L, leaves; O, oil; P, peels; R, root; Rb, root barks; Re, resin; Rh, rhizome; S, stems; Sb, stem bark; Se, seed; T, twigs; U, umbls; Un, underground parts; W, wood; Wh, whole herb) (10, 11, 89, 91-96).

The plant-derived coumarin-hemiterpene ethers (CHEs) and their sources (Abbreviations: A, aerial parts; B, bark; Br, branches; E, epigeal parts; Eo, essential oil; F, fruits; Fl, flowers; L, leaves; O, oil; P, peels; R, root; Rb, root barks; Re, resin; Rh, rhizome; S, stems; Sb, stem bark; Se, seed; T, twigs; U, umbls; Un, underground parts; W, wood; Wh, whole herb) (10, 92, 93, 96-98).

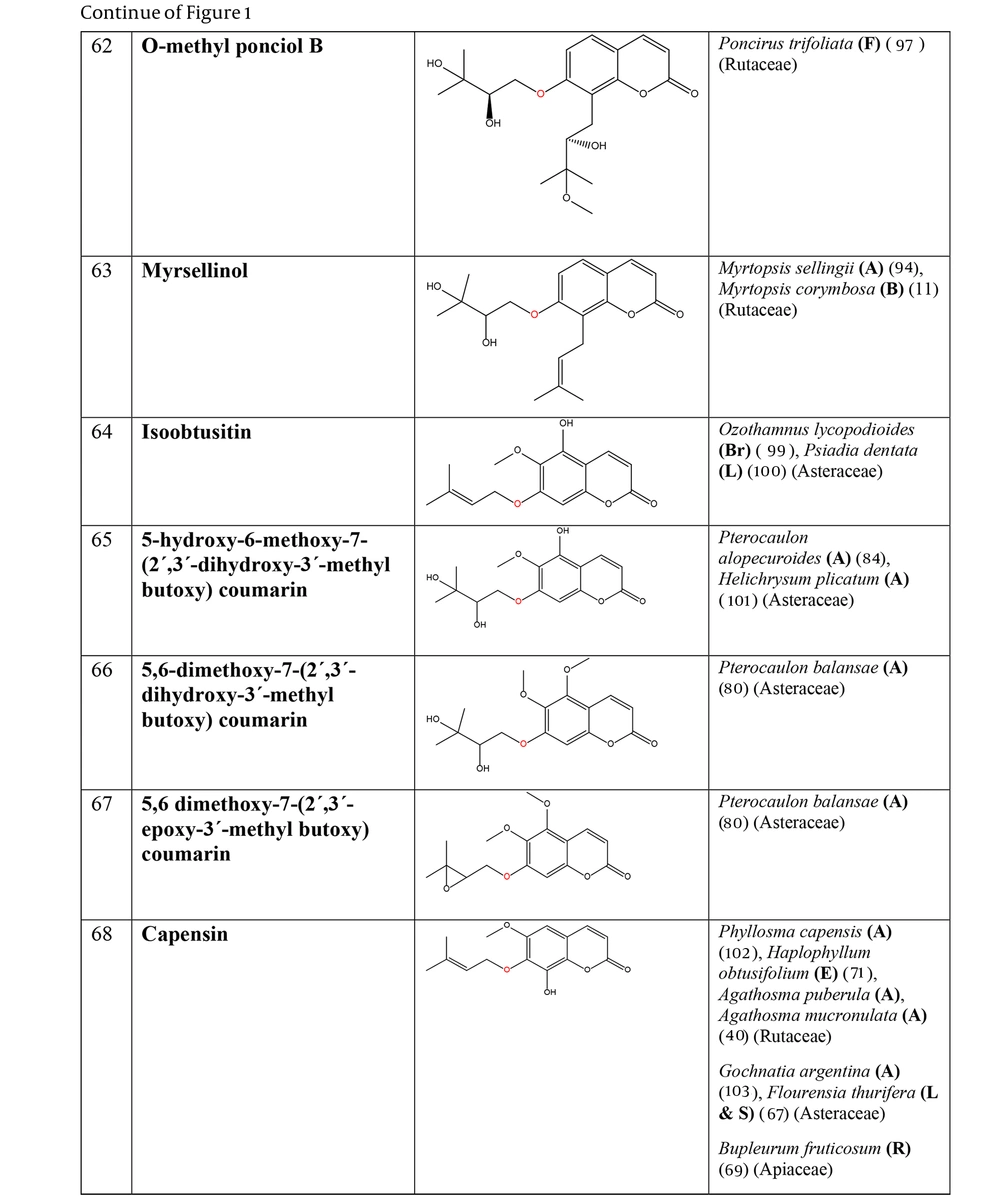

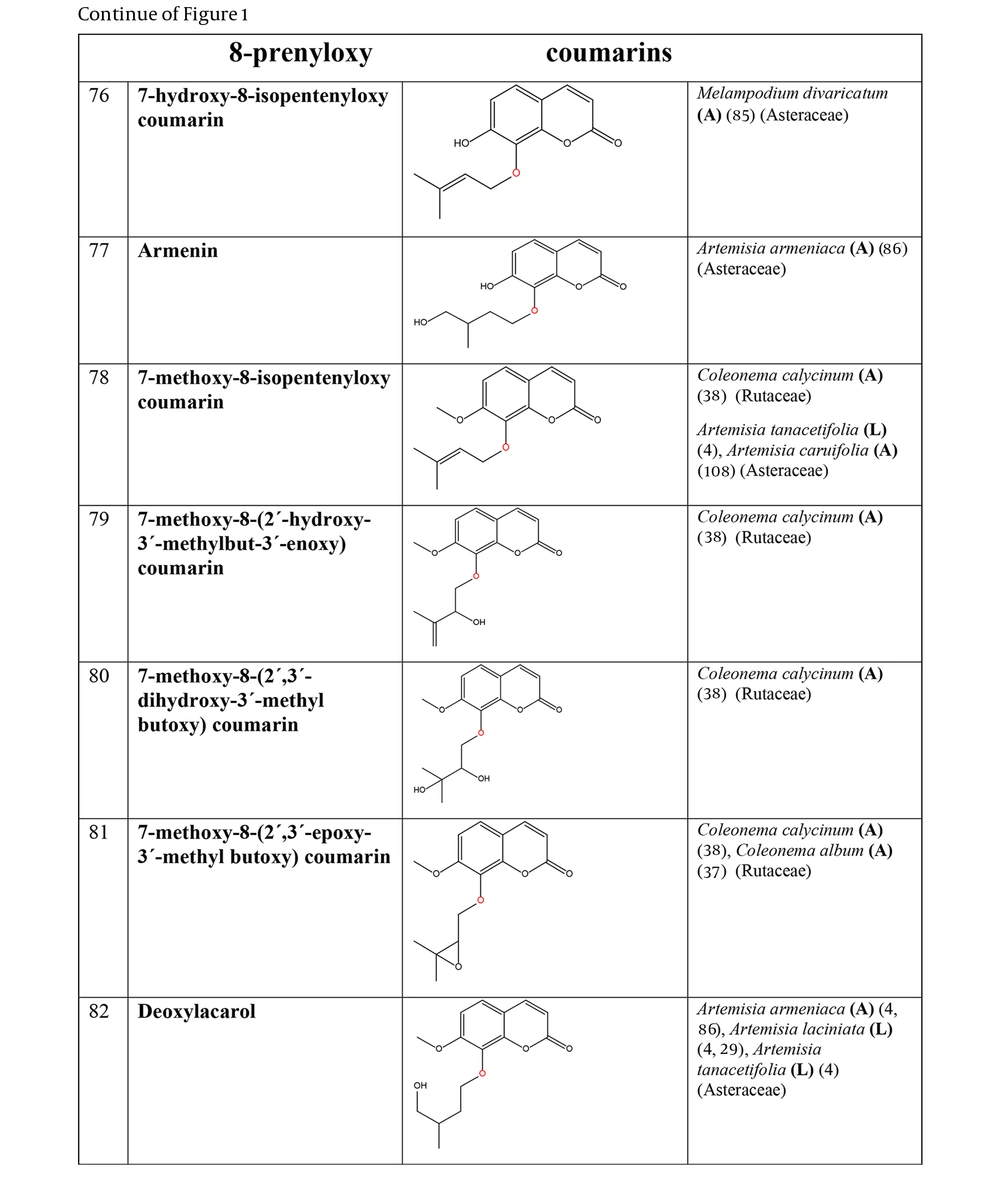

The plant-derived coumarin-hemiterpene ethers (CHEs) and their sources (Abbreviations: A, aerial parts; B, bark; Br, branches; E, epigeal parts; Eo, essential oil; F, fruits; Fl, flowers; L, leaves; O, oil; P, peels; R, root; Rb, root barks; Re, resin; Rh, rhizome; S, stems; Sb, stem bark; Se, seed; T, twigs; U, umbls; Un, underground parts; W, wood; Wh, whole herb) (11, 40, 67, 69, 71, 80, 84, 94, 97, 99-103).

The plant-derived coumarin-hemiterpene ethers (CHEs) and their sources (Abbreviations: A, aerial parts; B, bark; Br, branches; E, epigeal parts; Eo, essential oil; F, fruits; Fl, flowers; L, leaves; O, oil; P, peels; R, root; Rb, root barks; Re, resin; Rh, rhizome; S, stems; Sb, stem bark; Se, seed; T, twigs; U, umbls; Un, underground parts; W, wood; Wh, whole herb) (40, 71, 77, 87, 101, 104-107).

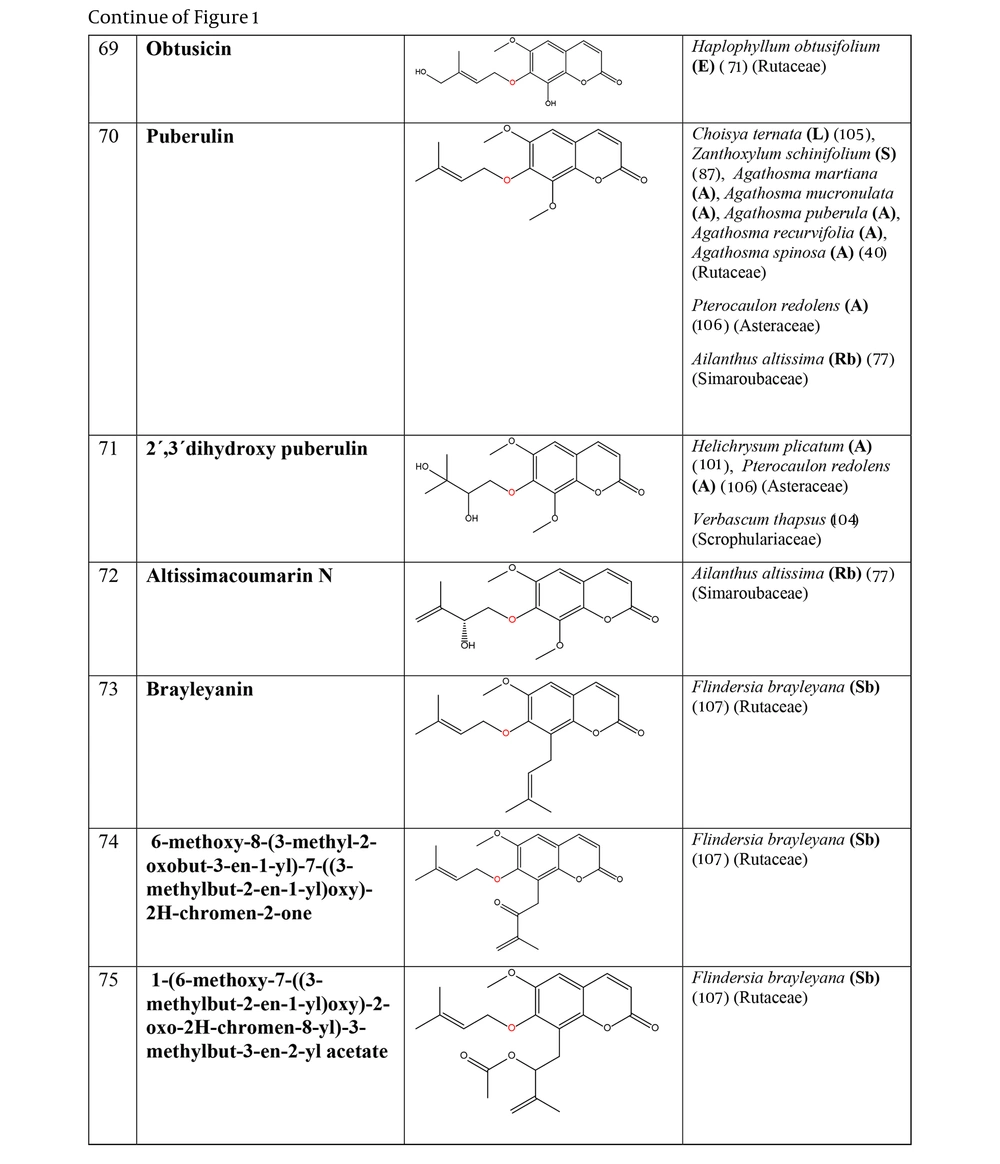

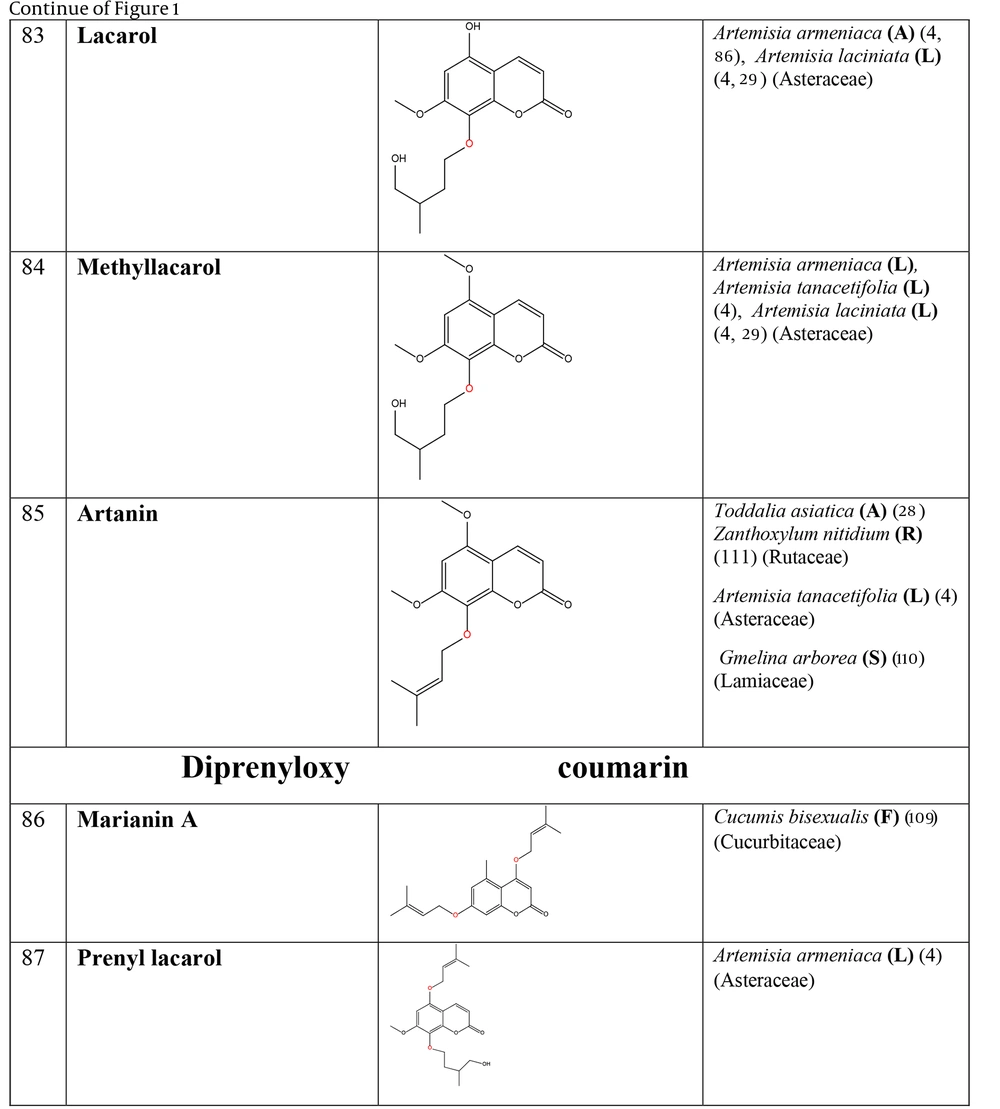

The plant-derived coumarin-hemiterpene ethers (CHEs) and their sources (Abbreviations: A, aerial parts; B, bark; Br, branches; E, epigeal parts; Eo, essential oil; F, fruits; Fl, flowers; L, leaves; O, oil; P, peels; R, root; Rb, root barks; Re, resin; Rh, rhizome; S, stems; Sb, stem bark; Se, seed; T, twigs; U, umbls; Un, underground parts; W, wood; Wh, whole herb) (4, 37, 38, 85, 86, 108).

The plant-derived coumarin-hemiterpene ethers (CHEs) and their sources (Abbreviations: A, aerial parts; B, bark; Br, branches; E, epigeal parts; Eo, essential oil; F, fruits; Fl, flowers; L, leaves; O, oil; P, peels; R, root; Rb, root barks; Re, resin; Rh, rhizome; S, stems; Sb, stem bark; Se, seed; T, twigs; U, umbls; Un, underground parts; W, wood; Wh, whole herb) (4, 28, 29, 86, 109-111).

Regarding to this table, there are no reports of 3-prenyloxy coumarins of plant origin. 4-prenyloxy coumarins and 6-prenyloxy coumarins have a very limited distributions. The findings suggest that 5-prenyloxy coumarins are more common, but they are restricted to the Rutaceae, Asteraceae, and Apiaceae families. 7-prenyloxy coumarins are the most prevalent NCHEs, found in 13 families. Among all known NCHEs, 7-isopentenyloxycoumarin and its 6-methoxy derivative are highly prevalent.

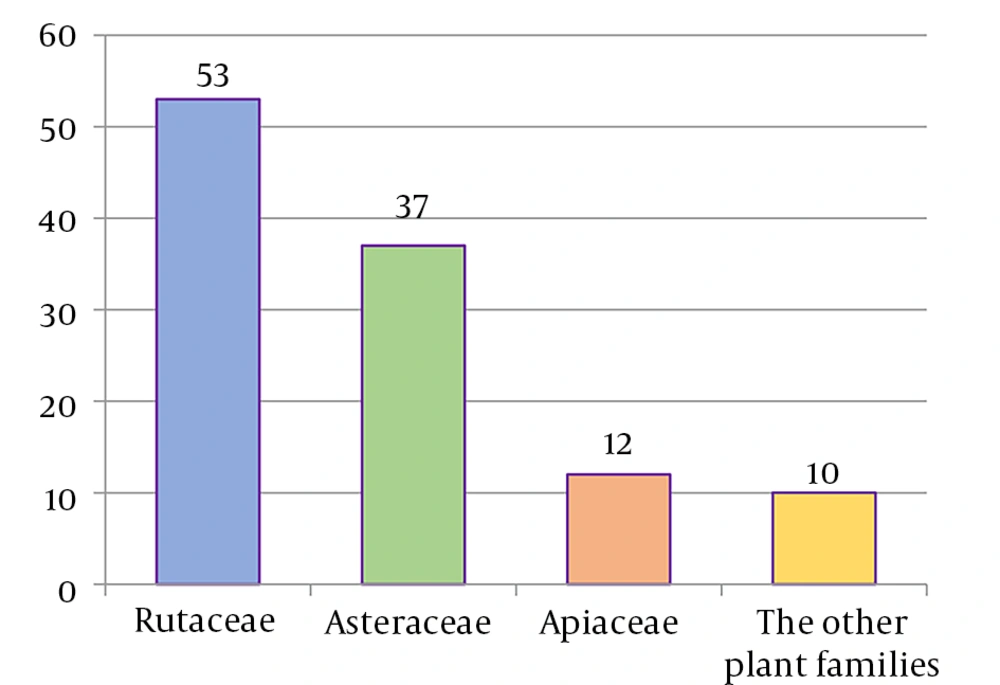

A remarkable point about 8-prenyloxy coumarins is that two-thirds of these compounds have been isolated from the Asteraceae (genus Artemisia). Prenyl lacarol and marianin A are NCHEs that contain two hemiterpene ether moieties. These two NCHEs are categorized in a distinct section named diprenyloxy coumarins. Figure 3 presents the occurrence of NCHEs in different plant families.

The Rutaceae (53 compounds), Asteraceae (37 compounds), and Apiaceae (12 compounds) families are the richest sources of NCHEs. However, a limited number of NCHEs (10 compounds) have been reported from the other plant families. The various types of NCHEs isolated from the three families — Rutaceae, Asteraceae, and Apiaceae — are displayed in Table 1.

| Variables | Families |

|---|---|

| Rutaceae (53 compounds) | |

| 4-prenyloxy coumarins | - |

| 5-prenyloxy coumarins (8 compounds) | Citrus reticulata (20), C. aurantifolia (21), C. medica (22), C. meyeri (23), C. limon (15, 24), Zanthoxylum nitidium (27), Toddalia asiatica (28) |

| 6-prenyloxy coumarins | - |

| 7-prenyloxy coumarins (40 compounds) | Agathosma collina, A. imbricata, A. martiana, A. mucronulata, A. mundii, A. recurvifolia, A. serpyllacea, A. spinosa, A. thymifolia, A. unicarpellata, A. puberula (40), Melicope lunu-ankenda (59), M. hayesii (41), M. semecarpifolia (42), M. vitiflora (43), M. borbonica (73), Diosma ramosissima, D. prama, D. recurva (40), D. acmaeophylla (39), Coleonema album (37), C. calycinum (38), C. aspalathoides (38), Clausena anisata (60, 92), C. indica (61), C. excavata (98), Citrus trifoliata (93), C. medica (72), C. limon (24), Choisya arizonica, Ch. mollis (90), Ch. ternata (105), Myrtopsis sellingii (94), M. corymbosa (11), Haplophyllum obtusifolium (71, 82), H. ramosissimum (83), Galipea panamensis (95), G. trifoliata (91), Zanthoxylum schinifolium (87), Z. nitidium (111), Poncirus trifoliata (62, 96, 97), Phyllosma capensis (102), Triphasia trifolia (10), Eriostemon spicatus (89), Flindersia brayleyana (107), Euodia vitiflora (35), Asterolasia phebalioides (36), Ptaeroxylon obliquum (65) |

| 8-prenyloxy coumarins (5 compounds) | C. calycinum (38), C. album (37), T. asiatica (28), Z. nitidium (111) |

| Diprenyloxy coumarins | - |

| Asteraceae (37 compounds) | |

| 4-prenyloxy coumarins (1 compound) | Gerbera crocea (19) |

| 5-prenyloxy coumarins (3 compound) | Artemisia laciniata (29) |

| 6-prenyloxy coumarins (2 compound) | Carduus tenuiflorus (33), Pterocaulon polystachyum (34) |

| 7-prenyloxy coumarins (23 compound) | P. polystachyum (13, 34), P. virgatum (74), P. alopecuroides (13, 84), P. balansae (80), Pt. redolens (106) Artemisia glauca (51), A. dracunculoides (75), Artemisia armeniaca (86), A. apiacea (88), A. laciniata (29), Haplopappus multifolius (5, 81), H. deserticola (44), Isocoma tenuisecta, I. acradenia, I. rusbyi (50), Ozothamnus rosmarinifolius (68), O. lycopodioides (99), Tagetes lucida (8, 9), Helianthus tuberosus (76), Heterotheca inuloides (49), Viguiera gardneri (66), Flourensia thurifera (67), Melampodium divaricatum (85), Psiadia dentata (100), Gochnatia argentina (103), Helichrysum plicatum (101) |

| 8-prenyloxy coumarins (7 compound) | Artemisia tanacetifolia (4), A. caruifolia (108), A. armeniaca (4, 86), A. laciniata (4, 29), M. divaricatum (85) |

| Diprenyloxy coumarins (1 compound) | A. armeniaca (4) |

| Apiaceae (12 compounds) | |

| 4-prenyloxy coumarins | - |

| 5-prenyloxy coumarins (5 compounds) | Seseli sibiricum (30, 31), S. rigidum (32), Angelica gigas (25), Notopterygium incisum (26) |

| 6-prenyloxy coumarins | - |

| 7-prenyloxy coumarins (7 compounds) | Heracleum mantegazzianum (63), H. dissectum (53), H. lanatum (54), Angelica gigas (70), A. archangelica (52), Notopterygium franchetii (58), N. incisum (26, 58), Ligusticum lucidum (7), Seseli libanotis (35), Bupleurum fruticosum (69), Pimpinella anisum, Anethum graveolens (52), Lomatium nevadense (55), Tordylium apulum (56), Zosima absinthifolia (57), Libanotis intermedia (35) |

| 8-prenyloxy coumarins | - |

| Diprenyloxy coumarins | - |

The following sections provide detailed descriptions of NCHEs in different plant families.

3.2. Natural Coumarin-Hemiterpene Ethers from Rutaceae

Almost half of the reports on the isolation of NCHEs have resulted from phytochemical investigations on Rutaceae members. There are no reports of 4-prenyloxy coumarins, 6-prenyloxy coumarins, and diprenyloxy coumarins in Rutaceae. The genera Citrus and Agathosma had the highest occurrence of 5-prenyloxy coumarins and 7-prenyloxy coumarins, respectively.

3.3. Natural Coumarin-Hemiterpene Ethers from Asteraceae

Asteraceae is the sole plant family in which NCHEs with all different substitution patterns (based on the attachment site of the hemiterpene ether portion) have been identified. The genera Pterocaulon and Artemisia had the highest number of 7-prenyloxy coumarins and 8-prenyloxy coumarins, respectively.

3.4. Natural Coumarin-Hemiterpene Ethers from Apiaceae

There are no reports of 4-prenyloxy, 6-prenyloxy, 8-prenyloxy, and diprenyloxy coumarins in Apiaceae.

3.5. Natural Coumarin-Hemiterpene Ethers from Other Plant Families

Several phytochemical findings have confirmed that other families, including Cucurbitaceae (109), Amaranthaceae (45, 46), Myrtaceae (47), Campanulaceae (48), Solanaceae (46), Polygalaceae (64), Convolvulaceae (6), Simaroubaceae (77) Thymelaeaceae (78), Theaceae (79), Scrophulariaceae (104), and Lamiaceae (110), also contain NCHEs. The NCHEs from the other plant families are summarized in Table 2. As is evident, most of these families have provided 7-prenyloxy coumarins, particularly 7-isopentenyloxycoumarin (6, 45-48, 64, 77-79, 104), while two families, Cucurbitaceae and Lamiaceae, possess a 4,8-diprenyloxy coumarin and an 8-prenyloxy coumarin, respectively (109, 110).

| Families | 4-prenyloxy Coumarins | 5-prenyloxy Coumarins | 6-prenyloxy Coumarins | 7-prenyloxy Coumarins | 8-prenyloxy Coumarins | Diprenyloxy Coumarins |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cucurbitaceae (Cucumisbisexualis) | - | - | - | - | - | Marianin A (109) |

| Amaranthaceae (Amaranthusretroflexus, Spinaciaoleracea) | - | - | - | 7-isopentenyloxycoumarin (45, 46) | - | - |

| Myrtaceae (Melaleuca alternifolia) | - | - | - | 7-isopentenyloxycoumarin (47) | - | - |

| Campanulaceae (Codonopsispilosula) | - | - | - | 7-isopentenyloxycoumarin (48) | - | - |

| Solanaceae (Lyciumbarbarum) | - | - | - | 7-isopentenyloxycoumarin (46) | - | - |

| Polygalaceae (Polygala sabulosa) | - | - | - | 6-methoxy-7-isopentenyloxycoumarin (64) | - | - |

| Convolvulaceae (Convolvulus trabutianus) | - | - | - | 6-methoxy-7-isopentenyloxycoumarin (6) | - | - |

| Simaroubaceae (Ailanthus altissima) | - | - | - | 6-methoxy-7-isopentenyloxycoumarin (77), Altissimacoumarin N (77), Puberulin (77) | - | - |

| Thymelaeaceae (Daphne oleoides) | - | - | - | Virgatenol (78) | - | - |

| Theaceae (Euryachinensis) | - | - | - | Haplopinol methyl ether, 6-demethyl obtusinin (79) | - | - |

| Scrophulariaceae (Verbascumthapsus) | - | - | - | 2´, 3´dihydroxy puberulin (104) | - | - |

| Lamiaceae (Gmelinaarborea) | - | - | - | - | Artanin (110) | - |

3.6. Chemotaxonomic Significance of Natural Coumarin-Hemiterpene Ethers

The NCHEs possess considerable chemotaxonomic significance, as a large number of them (71 compounds) have been identified exclusively in single plant families to date. The Rutaceae family has the highest number of unique NCHEs (40 compounds). Furthermore, more than three-fourths of the exclusive NCHEs in the Rutaceae family (31 compounds) are genus-specific or species-specific. Two genera, Citrus and Coleonema, provide six exclusive NCHEs, while the number of genus-specific NCHEs in Melicope, Galipea, and Myrtopsis is three, two, and one, respectively. It is noteworthy that Poncirus trifoliata, Flindersia brayleyana, and Eriostemon spicatus possess six, three, and two species-specific NCHEs, respectively. Additionally, each of the two species, Clausena anisata and Haplophyllum obtusifolium, contains one species-specific NCHE.

Nearly half of the exclusive NCHEs in the Rutaceae family (18 compounds) are 8-C-prenylated 7-prenyloxy coumarins that were observed in eight genera, including Myrtopsis, Poncirus, Clausena, Triphasia, Citrus, Galipea, Eriostemon, and Choisya. Besides, three species-specific NCHEs in F. brayleyana are the 8-C-prenylated 6-methoxy 7-prenyloxy coumarin derivatives. The structural pattern of 5-hydroxy 7-prenyloxy coumarin is restricted to the Poncirus and Clausena genera, while the pattern of 5-prenyloxy 7-hydroxy coumarin is characteristic of the genus Citrus and is specifically found in Citrus reticulata.

The occurrence of 23 exclusive NCHEs has been reported in the Asteraceae family. The genus Artemisia contains 10 unique NCHEs, among which four are species-specific to A. laciniata, and three are species-specific to A. armeniaca. Moreover, six exclusive NCHEs belong to the genus Pterocaulon, of which two are species-specific to Pterocaulon balansae, and the other two are species-specific to P. polystachyum, while P. virgatum provides one species-specific NCHE. Additionally, Melampodium divaricatum possesses two species-specific NCHEs, and one unique NCHE has been reported for each of the following species: Gerbera crocea, Carduus tenuiflorus, and Haplopappus multifolius.

Two other exclusive NCHEs in the Asteraceae family have been found in more than one genus (Ozothamnus, Psiadia, Pterocaulon, and Helichrysum). The substitution pattern of both of them is 5-hydroxy 6-methoxy 7-prenyloxy, which has not been observed in other plant families. Other exclusive NCHE substitution patterns observed in Asteraceae include 4-prenyloxy 5-methyl (found in the genus Gerbera), 6-prenyloxy 7-methoxy (found in the genera Carduus and Pterocaulon), 5,6-dimethoxy 7-prenyloxy (found in the genus Pterocaulon), 7-prenyloxy 8-hydroxy (found in the genera Artemisia and Melampodium), 5-hydroxy 7-methoxy 8-prenyloxy (found in the genus Artemisia), 7-hydroxy 8-prenyloxy (found in the genera Artemisia and Melampodium), and 5,8-diprenyloxy 7-methoxy (found in the genus Artemisia).

There are five NCHEs restricted to the Apiaceae family. These compounds exhibit two exclusive substitution patterns, including 5-methoxy 7-prenyloxy (found in Heracleum) and 5-prenyloxy 7-methoxy 8-prenyl (found in Seseli). Besides, three NCHEs are species-specific to Seseli sibiricum. One exclusive NCHE has been reported for each of the families Cucurbitaceae (Cucumis bisexualis), Theaceae (Eurya chinensis), and Simaroubaceae (Ailanthus altissima). The Cucurbitaceae family (C. bisexualis) provides a notable exclusive substitution pattern (4, 7-diprenyloxy 5-methyl).

In summary, the Rutaceae family possesses the highest number of exclusive NCHEs, following eight substitution patterns. Half of these patterns are not observed in other plant families. The 7-prenyloxy 8-prenyl pattern is found with the greatest abundance across eight genera. The Asteraceae family exhibits the highest diversity of unique substitution patterns, mainly with a distribution limited to a single genus (4 patterns) or two genera (3 patterns). Among all plant genera studied, Artemisia has the highest number of exclusive NCHEs (10 compounds). The Apiaceae and Cucurbitaceae families exhibit five and one exclusive NCHEs, respectively. All of these compounds also display specific substitution patterns that are observed exclusively in these two families. Moreover, one exclusive NCHE has been reported from each family, Theaceae and Simaroubaceae. However, similar substitution patterns have been observed in NCHEs from other families.

4. Conclusions

The CHEs are a class of coumarins in which a hemiterpene moiety (C5) is attached to the coumarin scaffold by O-prenylation. The plant-derived CHEs were abundantly isolated from the Rutaceae, Asteraceae, and Apiaceae families. However, these compounds have also been reported in 12 other plant families. 7-isopentenyloxycoumarin is the most common NCHE. Almost 80% of NCHEs have been exclusively isolated from a single plant family. The highest number of exclusive NCHEs was identified in the Rutaceae family, while the Asteraceae family exhibits the highest diversity of unique substitution patterns. Accordingly, NCHEs can be considered valuable chemotaxonomic markers.

4.1. Study Limitations

The number of phytochemical studies in some plant families and genera was not sufficient to draw definitive conclusions about the chemotaxonomic significance of isolated NCHEs.

4.2. Future Directions

The findings of this study may help researchers conduct phytochemical studies on the plant genera that are likely to be rich in this type of secondary metabolite. This, in turn, will increase our understanding of their chemotaxonomic significance.