1. Background

Epilepsy is the most common disorder of the central nervous system. It occurs due to the disruption of electrical activity, leading to acute and chronic changes in nerve function and mental abnormality (1). Epidemiologic studies show that 1% of people worldwide are affected by epilepsy and its prevalence is two to three times higher in African countries than in the rest of the world (2). In developed countries, there are 4 to 10 people with epilepsy per 10000 population (3). There is a relationship between the epilepsy prevalence and age so that it is more common in the first 10 years of life, especially in the first year (4). The abnormal discharge of nerve cells by various factors such as low blood sugar, oxygen deficiency, and infection makes imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory systems in the brain and leads to convulsion and the loss of consciousness (5).

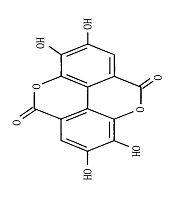

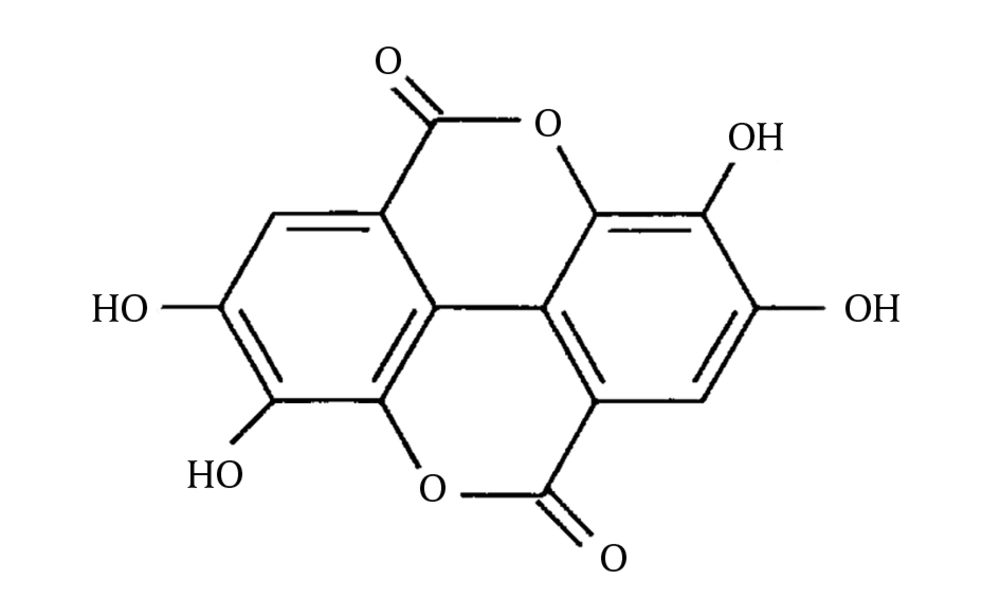

In the last decade, plants have found an important role in clinical application as natural resources of pharmaceutical products. Nowadays different types of herbal medicines are commercially available in various dosage forms in the market (6). The World Health Organization estimates that 80% of populations in Asian and African countries use traditional medicine for the remedy of disease (7). Ellagitannins are hydrolyzable tannins that have functions in cell membranes (8). When ellagitannins are exposed to acid or base, the ester bond is hydrolyzed to form ellagic acid as a gallic acid dimer (Figure 1).

Ellagic acid is found in plants such as pomegranate, walnut, strawberry, blueberry, eucalyptus, and oak (9). Because of the key role of these compounds in the treatment of cancer and cardiovascular diseases, they are considered as useful compounds in the human diet. Several studies confirmed that these effects are attributed to their antioxidant activity (10). Ellagitannins have antidepressant, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic properties, as well (11-13). Several studies showed that ellagic acid is useful for the treatment of colitis, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and anxiety and it can reduce the symptoms of nicotine dependence (14-18). In addition, ellagic acid has a protective effect on liver toxicity induced by carbon tetrachloride (19). It has been shown that ellagic acid considerably increases the activity of glutathione S-transferase and glutathione levels in cancer cells (20). Ellagic acid can make increases in the activity or induction of genes involved in the expression of superoxide dismutase, catalase, and NADPH quinones oxidoreductase and it has a neuroprotective effect on neurons against oxidative damage (21). As previously reported, ellagic acid has neuroprotective and antioxidant effects and increases the brain’s GABA levels and GABAergic transmission (22).

2. Objectives

This study was designed to evaluate and compare the effects of ellagic acid on two models of seizures in mice including maximal electroshock (MES)-induced convulsion for grand mal epilepsy and pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced seizure for absence epilepsy.

3. Methods

3.1. Experimental Animals

C57 albino mice in the weight range of 23 ± 3 g were purchased from the Research Center and Experimental Animal House of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (AJUMS). The mice were kept in standard cages at 23 ± 2°C under a 12-hour light/dark cycle. All animals had free access to food and water throughout the experiment and benefited from the diet and adequate water because dehydration and lack of adequate food could change the seizure threshold (23). The experiments were carried out at a certain time of day (10 a.m. to 14 p.m.). For adaptation to the environment and elimination of anxiety, the animals were put in the experiment place 30 minutes before the experiments started. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of AJUMS for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

3.2. Drugs and Chemicals

Ellagic acid and PTZ (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), diazepam ampoule (Caspian Pharmaceutical Co., Iran), phenytoin ampoule (Caspian Pharmaceutical Co., Iran), and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) (Merck, Germany) were purchased for research in this study. Ellagic acid was suspended in normal saline and CMC 0.1 % and stored at 4°C.

3.3. Selection of Doses

The approved dose of ellagic acid with no side effects in animal models is 778 mg/kg. However, based on a pilot study, ellagic acid was used at the doses of 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg in the current study (12). In addition, PTZ at 85 mg/kg and diazepam at 1 mg/kg were applied (23, 24).

3.4. Animal Models for Evaluation of Anticonvulsant Activity

3.4.1. Maximal Electroshock (MES) Seizure

In the mice model, MES seizure is often induced by an electric current of 50 mA and a frequency of 1500 Hz (21) for 0.2 second. However, the seizure intensity depends on the animal strain and the quality of the apparatus (25-27). In this study, the seizure was induced with an electric current of 50 mA at a frequency of 80 Hz for 0.2 second.

3.4.2. Pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-Induced Seizure

The convulsant doses of PTZ are between 85 and 150 mg/kg in mice. Thus, we needed first to determine the minimum required dose for seizure induction (28). In this study, PTZ was used at a dose of 85 mg/kg for seizure induction.

3.5. Experimental Protocol

3.5.1. Groups for MES-Induced Convulsions

The MES-induced convulsion groups included Group 1 (control) receiving normal saline (NS, 10 mL/kg) intraperitoneally (i.p.), Group 2 receiving phenytoin injection (50 mg/kg i.p.), and Groups 3, 4, and 5 receiving ellagic acid (25, 50, and 100 mg/kg i.p., respectively). After 30 minutes, the electric shock was inserted to animals’ ears with the intensity of 50 mA and the frequency of 80 Hz for 0.2 second through two pegs soaked with salt water. Then, the symptoms of seizures were evaluated by measuring the percent protection and duration of hind limb tonic extension (HLTE). The HLTE was the duration of the legs stretched backward and gathered inside the body.

3.5.2. Groups for PTZ-Induced Convulsions

The PTZ-induced convulsion groups included Group 1 (control) receiving NS (10 mL/kg i.p.), Group 2 receiving diazepam (1 mg/kg, i.p.), and Groups 3, 4, and 5 receiving ellagic acid (25, 50, and 100 mg/kg i.p., respectively). After 30 minutes, PTZ (85 mg/kg, i.p.) was injected to mice and then the latency to convulsions and Straub tail response, myoclonic activity duration, and the rate of mortality were recorded.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

All results are expressed as means ± SEM. To compare the effects of different doses of ellagic acid on seizure, the one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used. P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Effects of Ellagic Acid on MES-Induced Convulsions

As shown in Table 1, MES could induce seizures in the control and ellagic acid-treated groups while phenytoin prevented seizure in mice. The duration of HLTE was significantly different between the group treated with ellagic acid 25 mg/kg and the control group (P < 0.05). The increased dose of ellagic acid led to the longer duration of HTLE so that ellagic acid at the dose of 100 mg/kg could not prevent seizure. It seems that the higher doses of ellagic acid were not effective in the MES model of convulsion in mice.

Abbreviations: EA25, ellagic acid 25 mg/kg; EA50, ellagic acid 50 mg/kg; EA100, ellagic acid 100 mg/kg; NS, normal saline.

aData were analyzed by the one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD multiple comparison test.

bN = 6 in each group.

cValues are presented as means ± SEM.

dP < 0.05 as compared to MES-induced convulsion control mice.

4.2. Effects of Ellagic Acid on PTZ-Induced Convulsion

The results showed that PTZ could induce convulsion, which was associated with the decreased latency to convulsion and latency to Straub tail (Table 2); in addition, the duration of the myoclonic activity was significantly longer in this group than in the group treated with diazepam and ellagic acid. Ellagic acid effects on seizure were dose-dependent in reverse so that the latency to convulsion and latency to Straub tail were shorter in the group treated with ellagic acid 100 mg/kg than in the group treated with ellagic acid 25 mg/kg. These suggest that the anticonvulsant effects of ellagic acid decreased with increasing dose. Furthermore, ellagic acid 25 mg/kg resulted in the decreased duration of myoclonic activity, but this reduction was not statistically significant. Ellagic acid also led to a reduction in mortality rate (3/6, 2/6, and 2/6 in groups treated with ellagic acid 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg, respectively). Diazepam (1 mg/kg, i.p.) failed to show any convulsive activity in mice.

| Groupb | Dose | Latency to Convulsion (s)c | Latency to Straub Tail (s)c | Duration of Myoclonic Activity (s)c | Mortality Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 10 mL NS/kg, i.p. | 65.52 ± 2.48 | 90 ± 2 | 11.48 ± 0.59 | 6/6 (100) |

| Diazepam | 1 mg/kg, i.p. | 1280.2 ± 26.58d | 1800 ± 0d | 0 ± 0d | 0/6 (0) |

| EA 25 | 25 mg/kg, i.p. | 681.17 ± 9.17d | 690 ± 8.67d | 10.59 ± 1.02 | 3/6 (50) |

| EA 50 | 50 mg/kg, i.p. | 363.67 ± 13.11d | 375.83 ± 15d | 10.71 ± 0.28 | 2/6 (33.3) |

| EA 100 | 100 mg/kg, i.p. | 296.4 ± 5.86d | 298.8 ± 6.61d | 11.2 ± 0.20 | 2/6 (33.3) |

Abbreviations: EA25, ellagic acid 25 mg/kg; EA50, ellagic acid 50 mg/kg; EA100, ellagic acid 100 mg/kg; NS, normal saline.

aData were analyzed by the one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s SD multiple comparison test.

bN = 6 in each group.

cValues are presented as means ± SEM.

dP < 0.001 as compared to PTZ-treated control mice.

5. Discussion

Ellagic acid is a polyphenol with antioxidant properties. This compound is found in fruits such as pomegranate (29). Maximal electroshock (MES) is a model for the induction of generalized seizures of the tonic-clonic (grand mal) type. In this model, seizures are induced in animals by the electric current (27, 30). Recent reports have declared that MES represents a good model to study the early stages of epilepsy (31). The sudden discharge of neurons by the electric current occurs once the animal goes to the phase of HTLE and then returns to the initial state or dies. If the electric current is not adequate to create HLTE or the animal is protected by a drug, the animal will not enter this phase (32). In this study, the effect of ellagic acid was evaluated on the HLTE time. The results showed that only were mice in the group treated with ellagic acid 25 mg/kg protected against electroshock. The protective effects of orally administered ellagic acid on different models of seizure have been reported in the literature (22). Absence seizure occurs due to interferences in the function of GABA made by GABAA receptor agonists (33), similar to the one that occurs in the animal model of seizure induced by PTZ. Our results showed that the duration of myoclonic activity was not significantly different between groups treated with different doses of ellagic acid and the untreated control group. Nevertheless, the beneficial effects of ellagic acid on latency to convulsion and latency to Straub tail were seen at lower doses. Therefore, latency to convulsion and latency to Straub tail were significantly more in the group treated with ellagic acid 25 mg/kg than in the groups treated with ellagic acid 50 and 100 mg/kg. In addition, the lowest mortality (50%) was seen in the group treated with ellagic acid 25 mg/kg. The increased dose of ellagic acid was not effective in the reduction of seizure symptoms presumably because ellagic acid was toxic at higher doses (22). Previous studies indicated that flavonoids had the ability to affect the mood and some flavonoids showed antidepressant properties by inhibiting the monoamine oxidase (MAO) enzyme (34). Flavonoids such as flavonols and anthocyanins have anti-inflammatory effects in neurons (28). Animal studies confirm that rutin, vitexin, and naringenin have anticonvulsant effects (35-37). The anticonvulsant mechanism of ellagic acid is not fully determined; however, the elevation of GABAergic transmission is the most prominent mechanism (22). Furthermore, flavonoids can act as ligands for GABAA receptors and exhibit anticonvulsant effects (38, 39). They are also able to bind to the benzodiazepine site in GABAA receptors in the CNS (central nervous system). Many phenolic compounds can prevent ROS (reactive oxygen species) formation. Various studies have shown that ellagic acid has anti-mutagenic and antioxidant properties (40, 41). The role of oxidative stress in epileptogenesis and epilepsy initiation and progression has been proven (42). PTZ-induced convulsion is associated with oxidative stress and depletion of antioxidant levels in the brain (43, 44). This supports that ellagic acid may be an anticonvulsant due to its antioxidant properties. Previous studies confirmed that ellagic acid reduced free radicals formation in brain cells (10). Yang et al. showed that ellagic acid could inhibit the formation of reactive oxygen species in astrocytes (45).

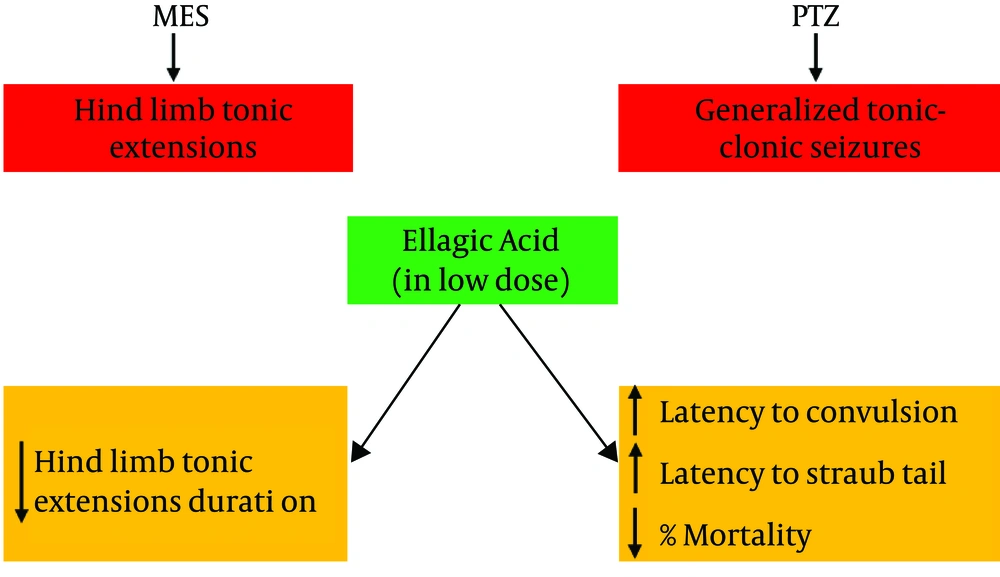

Based on the current study and previous studies, ellagic acid can alleviate convulsions in mice (Figure 2) through the suppression of oxidative stress and modulation of the GABAA pathway. In conclusion, we suggest that ellagic acid has neuroprotective effects in both PTZ and MES models of seizures and its anticonvulsant effects may be exerted through decreasing oxidative stress and increasing GABAA transmission in the brain.

Graphical abstract regarding the anticonvulsant effects of ellagic acid. Ellagic acid at low doses could decrease the duration of hind limb tonic extension in maximal electroshock (MES)-induced seizure in mice as a preclinical model of grand mal epilepsy. Furthermore, ellagic acid delayed the time to the first convulsion and Straub tail and decreased mortality in pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced convulsion in mice as a preclinical model of absence epilepsy.