1. Context

In 2019, cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome were first reported in Wuhan, Hubei province, China. The illness spread rapidly worldwide, resulting in serious health consequences for the global population and healthcare systems (1). By November 2024, over 776 million people had been diagnosed with the coronavirus infection, commonly known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus.

1.1. Morphology of Virion

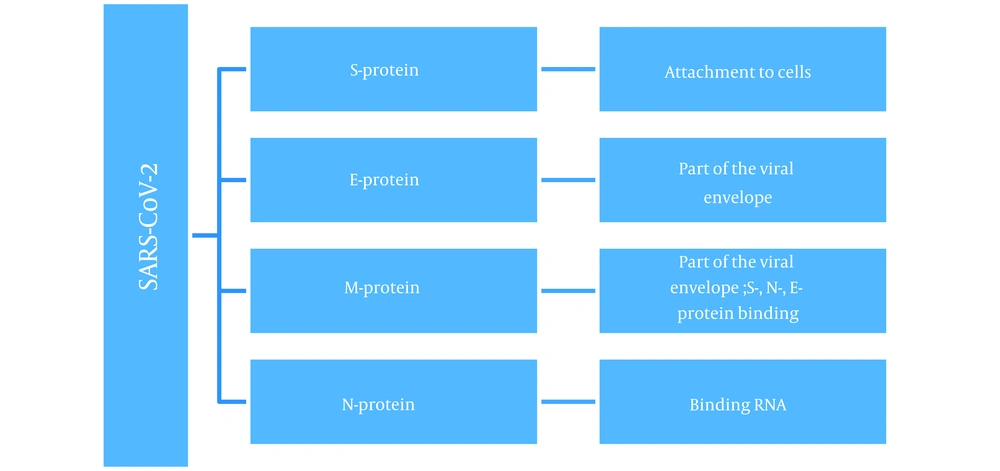

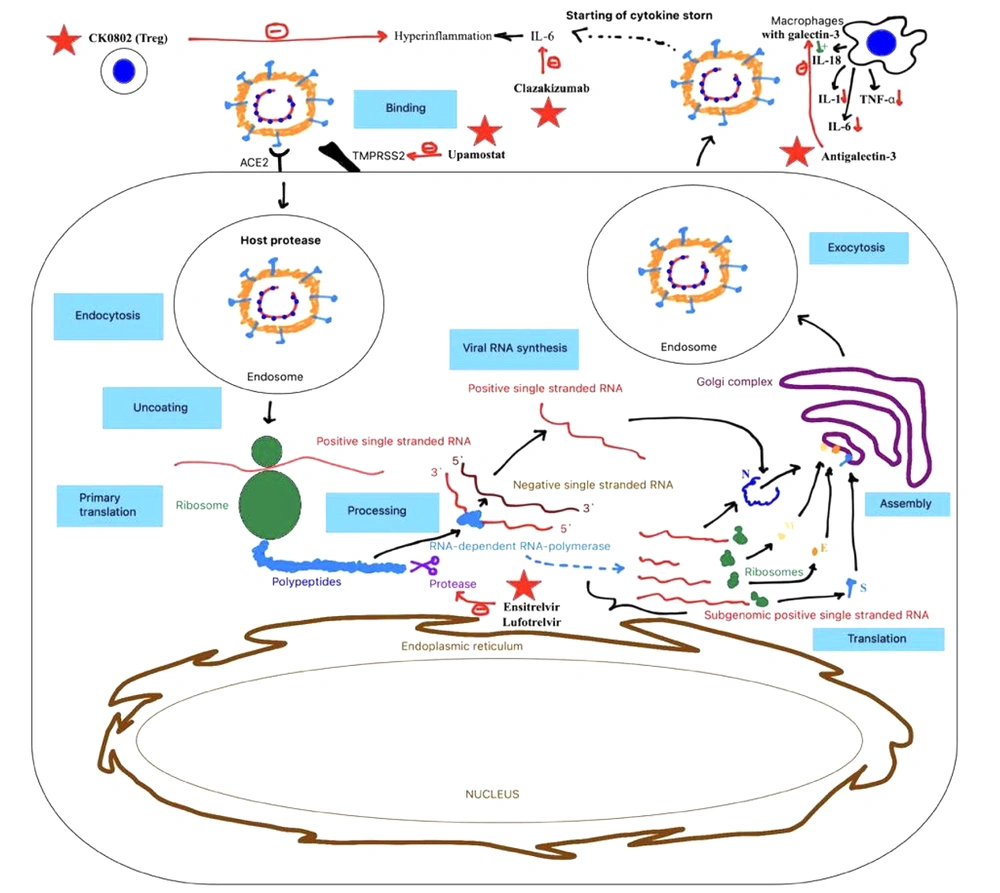

Syndrome coronavirus 2 is an enveloped virus with a positive ribonucleic acid (RNA) strand (+ssRNA) belonging to the Coronaviridae family of viruses (2). The virus contains four structural proteins (Figure 1): Spike (S) protein—a glycoprotein spike, envelope (E) protein, membrane (M) protein, and nucleocapsid (N) protein (3).

The S-protein is presented as a spike on the surface of the viral particle and is responsible for binding the virus to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors (4). These receptors are abundant on epithelial cells of the respiratory tract, such as type 2 alveolocytes (5, 6). The ACE2 receptors are also found on cells in the upper esophagus, ileal enterocytes, myocardial cells, proximal tubule cells of the kidneys, and bladder cells (7), leading to a wide range of possible virus-organ interactions.

Among the primary clinical manifestations of COVID-19, particularly the Omicron variant, are fever, cough, shortness of breath, and dyspnea. Although SARS-CoV-2 can enter various organs, it predominantly affects the respiratory system and blood vessels. Other systems, including the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, cardiovascular, hepatobiliary, renal, and central nervous systems, may also be impacted, though less commonly (8). These effects may result from mechanisms such as viral toxicity, ischemic injury caused by vasculitis, thrombosis or thromboinflammation, impaired immune regulation, and dysregulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (9).

As a result, SARS-CoV-2 can trigger a wide range of pathological processes. This raises critical concerns regarding effective antiviral and systemic treatment for patients diagnosed with coronavirus infection, as the extensive inflammatory and infectious process affects the entire organism, potentially leading to unfavorable outcomes or even death (10).

Currently, several commonly used treatment strategies exist for COVID-19. However, mutations, the emergence of novel strains, and the increasing resilience of the virus pose significant challenges. These developments reduce the effectiveness of standard treatment regimens, potentially rendering them inadequate (11, 12). This underscores the urgent need to develop new drugs and treatment approaches for SARS-CoV-2 to enhance the efficacy of medications and therapeutic plans. A summary of medicines in development is provided in Table 1.

| Drugs | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|

| Ensitrelvir | Inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease |

| Clazakizumab | Monoclonal antibody with a high affinity for human interleukin-6 |

| Upamostat | Block the attachment of the virus to the cell surface |

| CK0802 | Suppress intense immune responses |

| Antigalectin-3 | Decrease in the secretion of cytokines IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α by macrophages and dendritic cells |

| Lufotrelvir | Inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease |

List of Medicines in Development Against Syndrome Coronavirus 2

2. Ensitrelvir

Ensitrelvir (Xocova), a newly synthesized oral inhibitor of the SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease (Figure 2), has been used to treat patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 or asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection (13, 14). Clinical trials demonstrated that a 5-day course of ensitrelvir rapidly reduced viral titer and viral RNA levels between days 2 and 6 in the study population. Minor side effects included decreases in high density lipids (HDL) and triglyceride levels and increases in total bilirubin and iron levels. Importantly, these changes were asymptomatic and resolved without additional treatment.

A potential limitation of the study is that participants had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, making it challenging to assess the drug's standalone efficacy. However, this reflects current global realities, as a significant portion of the population has already been vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 (15).

3. Clazakizumab

Clazakizumab is a genetically engineered humanized monoclonal antibody with a high affinity for human interleukin-6 (IL-6) (16). As a direct ligand inhibitor that does not bind to circulating soluble receptors, clazakizumab may outperform IL-6R inhibitors, potentially offering greater benefits to patients with severe disease complicated by hyperinflammation (Figure 2).

Clinical trial results suggest that adding clazakizumab to standard therapy improves the 28-day survival rate without mechanical ventilation and enhances overall survival at 28 and 60 days compared to a placebo. However, a potential drawback is the reported association between clazakizumab and hypoxemia, which has been observed as a side effect. This raises concerns about its safety, as the treatment may lose effectiveness if the patient develops severe hypoxemia, warranting further evaluation of its risk-benefit profile (17).

4. Upamostat

Current treatment strategies for COVID-19 primarily target the virus itself rather than host factors, which also play a role in viral spread and entry. For instance, transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) facilitates the cleavage of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (18, 19). Upamostat, a prodrug of WX-UK1, targets the activity of multiple serine proteases (20). By doing so, upamostat blocks viral attachment to the cell surface and inhibits viral uptake by host cells (Figure 2).

A recent outpatient study on upamostat in patients exhibiting two moderate or severe symptoms of COVID-19, but not requiring hospitalization, demonstrated that the drug is safe and well-tolerated. It showed high bioavailability when self-administered and was intracellularly converted to WX-UK1. The study reported no adverse effects on liver, kidney, or hematological parameters, and no bleeding was observed. These findings suggest a modest anticoagulant effect, which could be potentially beneficial for COVID-19 patients, as coagulopathy is one of the most severe complications of the disease (21).

5. CK0802

Regular T-cells have shown potential in the treatment of COVID-19 (22) (Figure 2), as they can mitigate excessive immune responses (23). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1 RESOLVE clinical trial investigated the safety and early efficacy of CK0802, a cryopreserved allogeneic umbilical cord blood (UCB) Treg cell product, in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 (24). The study confirmed the safety of this therapy in critically ill patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) associated with COVID-19; however, its efficacy remains uncertain, necessitating larger clinical trials.

This treatment approach holds promise due to its convenience. The use of cryopreserved cell therapy products allows for application in intensive care unit settings without requiring complex on-site recovery of cell products. The therapy involves the infusion of ready-to-use CryoStore CS50N bags, which can be thawed bedside, and the capability to store medication stocks on-site ensures immediate availability (25). Overall, this method appears highly advantageous and has the potential to revolutionize COVID-19 treatment paradigms.

6. Antigalectin-3

In COVID-19, the severity of the disease correlates with an increase in galectin-3 levels (26), a mammalian β-galactoside-binding lectin (27). Galectin-3 plays a role in regulating systemic and pulmonary pro-inflammatory cytokine profiles by promoting IL-18 production by macrophages, which activates NLRP3 inflammasomes (28) (Figure 2). The therapeutic effect of antigalectin-3 involves reducing the secretion of cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, and tumor necrotic factor – alpha (TNF-α) by macrophages and dendritic cells (29), thereby mitigating inflammatory responses.

The investigational drug GB0139, an inhaled thiodigalactoside inhibitor of galectin-3, has demonstrated safety in COVID-19 patients. Clinical data have shown reductions in markers of inflammation, including C-reactive protein (CRP), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and chemokine CXCL10, in patients treated with GB0139 compared to those receiving a placebo (30). These findings suggest that targeting galectin-3 could provide a promising anti-inflammatory strategy for managing COVID-19.

7. Lufotrelvir

PF-00835231 is a small-molecule protease inhibitor designed to target the 3CL protease of SARS-CoV-2, an essential enzyme responsible for viral replication, and is also implicated in the earlier SARS outbreak (31-33) (Figure 2). In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1 clinical trial, single doses of its phosphate prodrug, lufotrelvir, administered via continuous infusion (50 mg to 700 mg over 24 hours), demonstrated safety (34).

Lufotrelvir has also shown potential as part of combination therapy, with a relatively low incidence of contraindications and side effects (35). A completed phase 1b study evaluating its safety and efficacy in hospitalized COVID-19 patients has produced promising results, paving the way for further exploration in future clinical trials.

8. Conclusions

The search for an optimal and most effective treatment strategy for COVID-19 is ongoing, with a primary focus on preventing and rapidly eliminating the virus from the body. Key criteria for such treatments include minimal side effects, efficacy across a range of patient severities (from mild to severe cases), and ease of access, storage, and administration. Efforts are also being made to test combination therapies with existing drugs to enhance their effects, accelerate action, and mitigate side effects.

While the efficacy of many new drugs against COVID-19 remains unproven in large-scale clinical trials, early research data provide a foundation for further testing. Additionally, the use of innovative drug delivery systems may play a role in simplifying treatment processes in the near future. In conclusion, the primary challenge lies in systematizing all available information to devise the most effective treatment strategy for managing this infection.

8.1. Limitations

Based on our analysis, it is important to note that the new treatment options are still undergoing pre-clinical and clinical research, and therefore, it cannot be stated with absolute certainty that they offer comprehensive treatment solutions.

Moreover, the development of these new treatment options is driven by the increasing emergence of therapy-resistant viral particles, which pose a significant new challenge to healthcare systems.

Additionally, there is growing evidence of adverse reactions associated with medications targeting cytokine storms, highlighting another critical factor that must be considered in the development of new treatments for COVID-19.