1. Background

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) refers to a continuum of physiological, biochemical, clinical, and metabolic factors (1) and is a multifactorial condition characterized by abdominal obesity, elevated glucose levels, hypertension, and altered lipid metabolism (2). The underlying pathophysiology of MetS is complex and not fully understood, involving a combination of genetic predispositions, advancing age, unhealthy lifestyles, and excessive calorie intake (3). Obesity plays a central role in the development of MetS (4). The global prevalence of MetS varies significantly, ranging from 12.5% to 31.4%, depending on the diagnostic criteria used (5). A recent study in Iran reported that the prevalence of MetS among women is approximately 34% (6). The worldwide rise in obesity has contributed to an increase in both the incidence and earlier onset of MetS (7).

There are several definitions of MetS, but the most widely accepted is that of the adult treatment panel III (ATP-III). According to ATP-III, a diagnosis of MetS requires the presence of at least three of the following five criteria: Abdominal obesity (waist circumference > 102 cm in men and > 88 cm in women), hypertension (> 130/85 mmHg), dysglycemia (fasting blood sugar > 110 mg/dL), hypertriglyceridemia (> 150 mg/dL), and low HDL levels (< 40 mg/dL in men and < 50 mg/dL in women) (8).

Mothers play a crucial role in societal health, and the method of childbirth has long been considered a key indicator of social health (9). In recent decades, the rate of cesarean section deliveries has risen dramatically, exceeding recommended norms and accounting for 43% of all births in some countries (10). Cesarean delivery is associated with certain maternal and neonatal complications (11, 12). In parallel with the increasing rate of cesarean sections, there has been a rise in obesity and immune-related disorders, such as type 1 diabetes, allergies, and celiac disease (13-15).

According to clinical observations, abdominal obesity appears to be more prevalent in women with a history of cesarean section (CS) (16). A growing body of evidence suggests that maternal obesity may independently increase the risk of undergoing a CS delivery (6, 17, 18). One possible explanation for the development of metabolic syndrome (MetS) following cesarean delivery is the increase in abdominal obesity. Research has shown that visceral and intra-abdominal fat, unlike subcutaneous fat, is linked to inflammation. The accumulation of abdominal fat can lead to insulin resistance and a higher concentration of toxic free fatty acids in the portal circulation, which can contribute to the development of MetS. Conditions such as hypertension, pre-diabetes, diabetes, and cardiovascular events, all of which are criteria for MetS, are associated with abdominal obesity (19-21).

2. Objectives

However, to the best of our knowledge, no comprehensive study has been conducted on this specific topic. Given the importance of maternal health, the rising prevalence of MetS in society, and the role of obesity as a key determinant, this study aimed to determine the prevalence of MetS in women with a history of either natural vaginal delivery or cesarean section.

3. Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted using data registered in the Sib database at Ilam University of Medical Sciences, Iran, in 2020 - 2021. Ethical approval was granted by the Ilam University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee (IR.MEDILAM.REC.1399.110).

Women with a history of either CS or natural childbirth, who visited health clinics in Ilam city between February 20, 2020, and February 20, 2021, were included in the study. A list of 11 health clinics in Ilam city was created, and three clinics were selected through simple random sampling. The number of women covered by each clinic was then determined, and the sample size was estimated by calculating the sample weight based on the population covered by each clinic. Simple random sampling was employed to recruit women from the selected health clinics. The sample size was determined using a prevalence rate of MetS in Iranian women, with P = 35%, α = 0.05, and d = 0.1, resulting in the selection of 350 eligible women through multistage sampling.

3.1. Inclusion Criteria

Women aged 30 - 40, with a history of two births (either natural or cesarean section), and for whom at least three years had passed since their last birth, were included in the study.

3.2. Exclusion Criteria

Women whose information in the Sib database was incomplete, those with a history of multiple births, women with a history of MetS before their first or second pregnancy, and those with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) or any other chronic diseases (renal, rheumatological, etc.) were excluded from the study.

Data collected from the Sib database included demographic information, the number of visits, services provided to the mother, breastfeeding history, prior pregnancies, and clinical and paraclinical information. These were gathered using a researcher-developed checklist. In this study, MetS was diagnosed according to the NCEP ATP III criteria (22). According to these criteria (23), a diagnosis of Metabolic Syndrome requires the presence of any three of the following five factors: Abdominal obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, low HDL cholesterol, elevated blood pressure, or impaired fasting glucose.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative variables were expressed as means and standard deviations, while qualitative variables were presented as absolute and relative frequencies. A t-test was employed to assess the significance of differences between the NVD and elective CS groups in predicting MetS outcomes. Logistic regression models were used to identify factors associated with the probability of having MetS. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated based on the logistic regression analysis results. Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA 12 software, with a statistical significance level set at P < 0.05.

4. Results

In this study, 350 women with a mean age of 35.2 ± 2.95 years were assessed, divided into two groups: NVD (n = 175) and CS delivery (n = 175). Metabolic syndrome (MetS) was identified in 53 women (30.3%) in the CS group and 32 women (18.3%) in the NVD group. As shown in Table 1, significant differences were observed between the CS and NVD groups regarding BMI, waist circumference, fasting blood sugar (FBS), breastfeeding duration, and lipid levels. Other descriptive variables are summarized in Table 1. Women without MetS had a longer breastfeeding duration compared to those with MetS (Table 2).

| Characteristics | NVD; (N = 175) | CS Delivery; (N = 175) | P-Value; (t-Test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 35.02 ± 3.01 | 35.31 ± 2.90 | 0.36 |

| BMI, (kg/m2) | 26.16 ± 4.47 | 28.27 ± 4.38 | < 0.001c |

| Breastfeeding (mo) | 11.77 ± 3.12 | 10.83 ± 2.28 | 0.001c |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 111.67 ± 10.40 | 111.09 ± 9.20 | 0.58 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 71.61 ± 8.83 | 73.61 ± 6.88 | 0.02c |

| Triglyceride, mgdL | 126.05 ± 21.27 | 135.91 ± 24.69 | < 0.001c |

| Cholesterol, mgdL | 172.04 ± 20.12 | 181.70 ± 14.24 | < 0.001c |

| HDL, mgdl | 47.13 ± 10.63 | 47.54 ± 8.38 | 0.69 |

| FBS, mgdl | 82.78 ± 9.78 | 84.90 ± 8.66 | 0.03c |

| HbA1c (%) | 4.07 ± 2.78 | 3.88 ± 0.39 | 0.75 |

| A_2hpp, mgdL | 115.48 ± 17.33 | 117.59 ± 16.19 | 0.24 |

| Waist size, cm | 86.57 ± 7.81 | 91.75 ± 9.39 | < 0.001c |

Abbreviations: BMI, Body Mass Index; BP, blood pressure; HDL, high density lipoprotein; FBS, fasting blood sugar; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; A_2hpp, 2-hour postprandial glucose

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Quantitative variables were compared between two groups using the Student's t-test.

c P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

| Variables | Metabolic Syndrome | Crude OR (95% CI) | P-Value d | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-Value e | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 85) | No (n = 265) | |||||

| Age (y) | 35.22 ± 3.18 | 35.14 ± 2.88 | 1.01 ± 0.93 - 1.10 | 0.83 | - | - |

| Breastfeeding, (mo) | 9.68 ± 2.37 | 11.82 ± 2.69 | 0.71 ± 0.64 - 0.80 | < 0.001 | 0.71 ± 0.64 - 0.80 | < 0.001 |

| Mode of delivery | ||||||

| CS delivery | 53 (30.29) | 122 (69.71) | 1 c | - | 1 | - |

| NVD | 32 (18.29) | 143 (81.71) | 0.52 (0.31 - 0.85) | 0.009 | 0.57 (0.34 - 0.97) | 0.04 |

Abbreviations: NVD, natural vaginal delivery; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD.

b The significance level was considered as 0.05.

c Reference category.

d P Value for crude OR.

e P Value for adjusted OR.

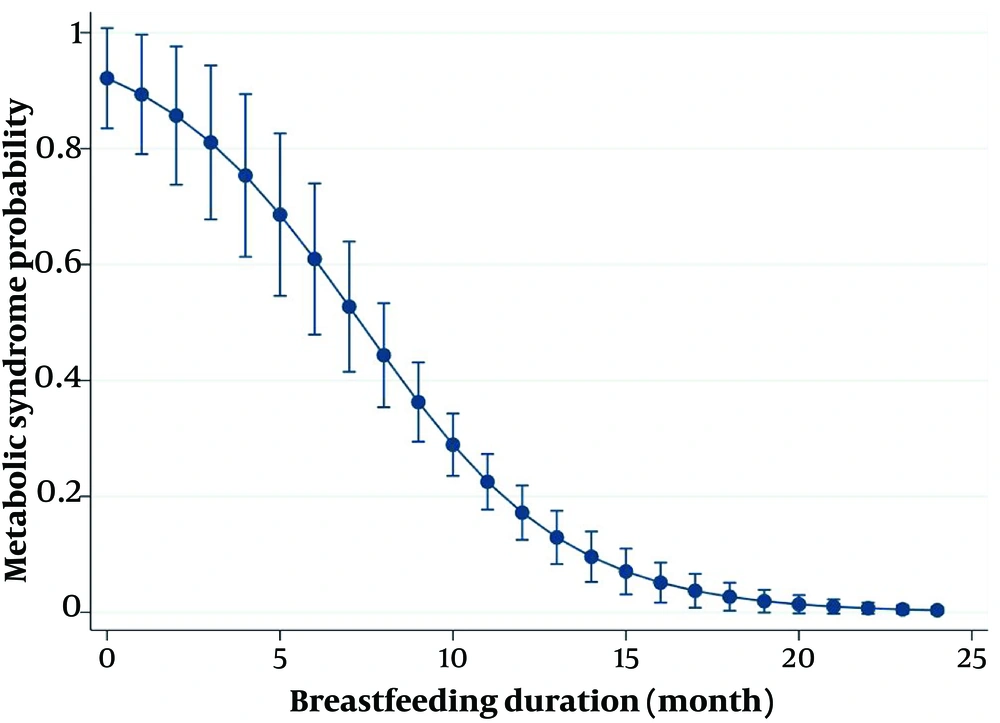

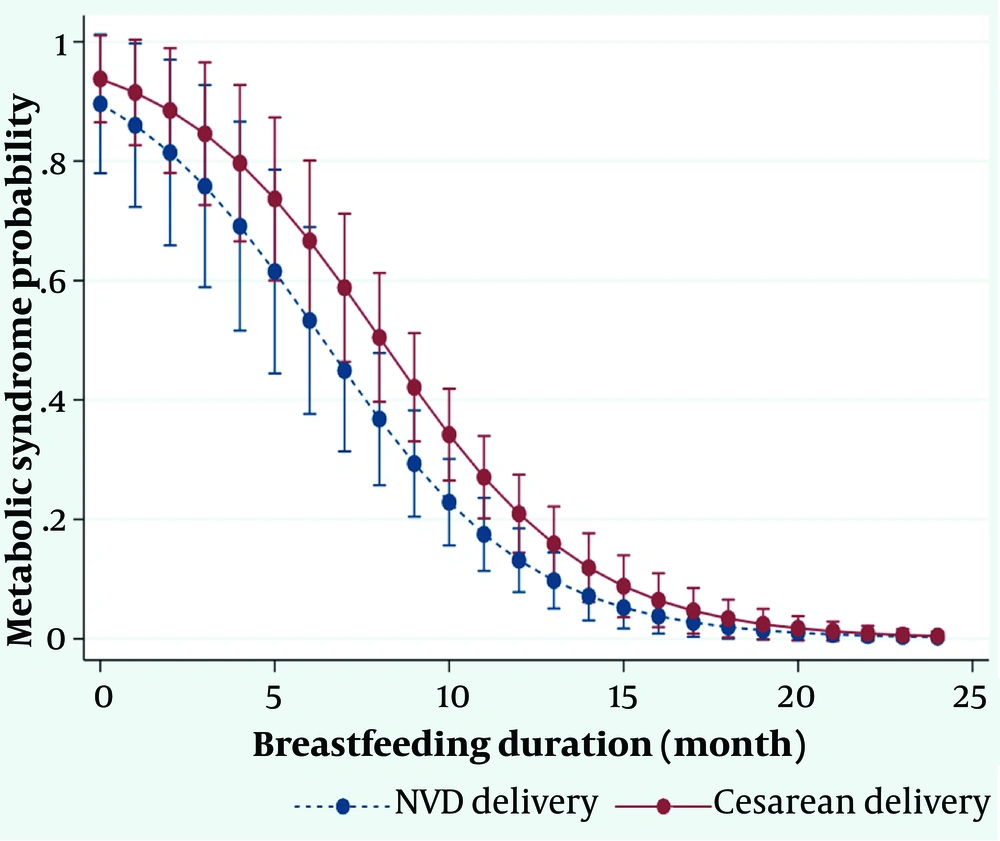

Univariate analysis indicated that breastfeeding (P < 0.001) and NVD (P = 0.009) were associated with a reduced risk of MetS (P < 0.05) (Table 2). The odds ratio (OR) of developing MetS was nearly twice as high in women undergoing CS compared to those with NVD (OR = 1.94, 95% CI: 1.18 - 3.20, P = 0.009). Each year increase in breastfeeding duration decreased the likelihood of MetS by approximately 30% (Table 2 and Figure 1).

In the final regression model, adjusted for breastfeeding duration and age, the type of delivery was significantly associated with the risk of MetS. Women in the NVD group had a 33% lower likelihood of developing MetS compared to those in the CS group (OR = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.34 - 0.97, P = 0.04), confirming that NVD served as a protective factor against MetS (P = 0.04) (Table 2). Figure 2 shows that while the prevalence of MetS was higher in the CS group than in the NVD group, this difference was modulated by an increase in breastfeeding duration. Our findings demonstrated that for each additional month of breastfeeding, the odds of developing MetS decreased by 29% (OR = 0.71, 95% CI: 0.64 - 0.80, P < 0.001). Notably, none of the mothers who breastfed for more than 20 months were diagnosed with MetS, regardless of whether they had NVD or CS delivery.

5. Discussion

In the present study, we aimed to compare the prevalence of MetS in women with a history of CS or NVD. The study of metabolic syndrome and the factors influencing it after childbirth is of great importance given the rising prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndrome in women (24). In this study, 30% of mothers who underwent CS and 18% of mothers with a history of NVD were identified with MetS. Studies have revealed that an increase in maternal BMI is also linked to a rise in emergency CS delivery rates (17, 25-27). Research has indicated that CS is associated with slight increases in blood pressure, BMI, and fat mass, but not with other metabolic risk factors (28). Metabolic syndrome is connected to various reproductive factors, such as the onset of menarche, the number of births, and the age at first birth (29). However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the relationship between mode of delivery and metabolic syndrome in women.

The OR of developing MetS in women with a history of CS was nearly double that of mothers who had NVD. Specifically, the OR for developing MetS in women with NVD was found to be 0.57, indicating a 33% lower likelihood of MetS in these women compared to those who underwent CS. This finding suggests that NVD may be a protective factor against MetS. Despite this result, we did not find any studies directly linking metabolic syndrome to mode of delivery. Abdominal obesity following cesarean delivery is one factor that may explain the higher rate of MetS among women who delivered via this method. Studies indicate that visceral and intra-abdominal fat, unlike subcutaneous fat, can promote inflammation. Additionally, abdominal fat has been linked with insulin resistance, leading to a higher concentration of toxic free fatty acids in the portal blood flow, which predisposes women to metabolic syndrome (16, 17, 19). Abdominal obesity is also associated with an increased risk of hypertension, pre-diabetes, diabetes, and cardiovascular events, all of which are risk factors for metabolic syndrome (20, 21).

Mothers who had NVD and did not have MetS were found to have a longer duration of breastfeeding. Our findings align with a cross-sectional study conducted in Poland, which indicated that women who breastfed had a lower rate of MetS (30). Similarly, the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study demonstrated that women may be more protected against MetS if they breastfeed for up to 12 months (31). However, another study conducted three years postpartum found no dose-response relationship between the duration of lactation and MetS (32). These varying results may be attributed to factors such as selection bias, differences in study timeframes, declines in breastfeeding rates, or unmeasured biomarkers in the studies.

Univariate analysis in our study revealed that both breastfeeding and NVD were strongly associated with a reduced risk of MetS. Specifically, the duration of breastfeeding was significantly linked to a decreased likelihood of MetS, with each additional year of breastfeeding lowering the risk by nearly 30%. The prevalence of MetS was higher among women with a history of CS delivery compared to those with NVD. Importantly, we found that the difference in MetS prevalence between the two delivery methods diminished with an increase in breastfeeding duration. Notably, mothers who breastfed for more than 20 months in either group had zero prevalence of MetS.

Additionally, other studies have reported that breastfeeding has a protective effect against the development of MetS after delivery, with breastfeeding for 1 to 1.5 years significantly reducing the risk (31). Experimental research has also indicated that not breastfeeding may be associated with weight gain (33), obesity (34), and MetS (35) postpartum.

Altogether, women with a history of cesarean section are advised to follow healthcare guidance and undergo appropriate preventive measures to reduce the risk of abdominal obesity and MetS.

Our study has several limitations. First, its cross-sectional design limits the ability to infer causal relationships. Secondly, while we found an association between metabolic syndrome and mode of delivery, it is important to determine whether this relationship is causal or influenced by confounding factors. Third, the small sample size necessitates caution when interpreting the results.

5.1. Conclusion

This study found that women who had undergone cesarean section were more likely to develop metabolic syndrome compared to those who had natural vaginal delivery (NVD). Since we did not assess or compare certain confounding variables, such as BMI, waist circumference, and lipid levels between the NVD and CS groups at the time of delivery, we cannot rule out their influence on the results. Therefore, we cannot definitively conclude that mode of delivery is a direct predictor of MetS. Additionally, our findings suggest that increased breastfeeding duration and the choice of NVD are associated with a lower likelihood of MetS. As a result, obstetricians and midwives should consider the potential risk of MetS when deciding whether to perform elective CS. Moreover, planning to reduce the rate of unnecessary cesarean sections is recommended.