1. Background

Diabetes and hepatitis are among the most common diseases around the world (1). Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major cause of mortality and morbidity globally, and is also the cause of about 25% of chronic liver diseases and hepatocellular carcinomas (2). It is estimated that 3% of the world's population (170 million people) are infected with hepatitis C and 55 - 80% are infected with chronic infections (2). In 2002, the number of diabetic patients was 177 million, and it is projected to increase to 300 million by 2025 (3). More than 171 million people around the world suffer from diabetes and this number will rise to 366 million by 2030. Most diabetic patients live in countries with a high economic level and it will be prevalent at ages older than 65 years until 2050, while in countries with middle to low economic levels, most diabetic patients will be in the age range of 45 - 64 until 2055.

In addition, HCV causes extrahepatic symptoms, including endocrine and thyroid diseases and diabetes (4). In patients with chronic liver diseases, progressive liver fibrosis is the cause of the progression of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Although diabetes occurs at the early stages of liver diseases (5), the results of a study revealed that the prevalence of diabetes in people with HCV is more than that of the general population (6). Preliminary studies have introduced hepatitis C infection as an additional risk factor for the progression of diabetes mellitus (7). However, some of the factors that increase the prevalence of these diseases have been mentioned, including ages more than 40 years, obesity, severe liver fibrosis, and family history of diabetes (8).

Hepatitis C causes the accumulation of lipids in the liver, while a fatty liver cannot absorb excess glucose from the blood; therefore, blood glucose levels increase. Most patients with hepatitis C have insulin resistance. Most diabetic patients are at higher risk of HCV due to hospitalization and multiple blood sampling and surgeries. In a study, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus in HCV+ patients was higher than that in healthy individuals (9).

About two billion people in the world are exposed to HBV, and about 350 million people are suffering from hepatitis B virus (10). In a study, the HBV prevalence in patients diagnosed with diabetes was above 60% and it was concluded that the prevalence of HBV in diabetics is 1.6 times higher than that in people without diabetes (10). Mekonnen et al. (2014) and Cai et al. (2015) found that the prevalence of HBs Ag was similar in diabetics and non-diabetics, and there was no definitive association between diabetes and HBV (10, 11).

Unfortunately, the number of patients with diabetes is increasing daily, and its complications develop in 75% of the total diabetic population (12-14).

2. Objectives

This study was conducted according to several studies that indicated the association of hepatitis C or B with diabetes and the negative effects that each of these two diseases (hepatitis and diabetes) may have on the outcome of each other.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This case-control study was conducted in Birjand, the capital of South Khorasan province, Iran, in 2018. The study population consisted of 5,000 individuals aged 15 - 70 years.

A multistage sampling method (clustering and random) was implemented. A total of 250 clusters were identified according to the Birjand City Postal Department, and in each cluster, 20 subjects were selected. Then, in this case study, which was conducted at the Hepatitis Research Center, a sample size of 85 people was obtained using the following Formula by substituting the values below (15):

α= 0.05, p2= 0.69, p1 = 0.137, and β = 0.8

Five members of the study group were excluded from the study due to underlying liver disease other than hepatitis. Finally, 80 patients with hepatitis B or C plus 160 patients as a control group were included in the study. As seen, the number of non-hepatitis patients, who were randomly selected, was almost twice the case group members that were matched for age range, sex, and body mass index.

3.2. Measures

The selected people were visited at their homes and invited to participate in sampling for serological diagnosis of hepatitis B and C after the objectives were explained to them and written informed consent was obtained from them. After the participants filled the forms, the researcher asked questions on demographic, specific, and risk factors such as previous blood injections, intravenous drug abuse, and blood transfusion (14).

In both groups, fasting blood glucose was measured according to one of the definitions of diabetes, and subjects who had blood glucose levels higher than 126 mg/dL twice were considered diabetic people according to the criteria of WHO (16). All the selected subjects had fasting blood glucose levels of higher than 126 mg/dL twice and the prevalence of diabetes was determined and compared in both groups. Demographic characteristics (age, sex, occupation, marital status, education, past medical history, family history of diabetes, BMI, etc.) and laboratory factors such as cholesterol, TG, LDL, HDL, and HbA1c were measured in all the subjects, and entered into the information form. Liver ultrasonography was also performed for patients with high blood glucose. To show us as soon as possible if there are changes in the size of the liver or signs that indicated the progression of liver disease (such as fatty liver and fibrosis). This study was approved with IR.BUMS.REC.1395.317 ethical code at Birjand University of Medical Sciences.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed by SPSS version 23 software using descriptive statistics (percentage, mean, standard deviation, chi-square test, and Fisher exact test) at a significance level of α = 0.05.

4. Results

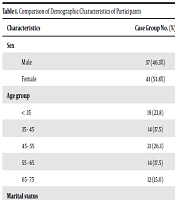

A total of 240 patients [80 cases (33.3%) including 75 patients with hepatitis B, three with hepatitis C, and two with hepatitis B and hepatitis C; and 160 (66.7%) controls] were enrolled. Of them, 111 (46.3%) were females and 129 (53.8%) were males, with no statistically significant difference between the case and control groups in terms of gender (P = 1.0), age range (P = 1), BMI (P = 0.69), marital status (P = 0.11), job (P = 0.38), and education (P = 0.31) (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Case Group No. (%) | Control Group No. (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1 | ||

| Male | 37 (46.3%) | 74 (46.3%) | |

| Female | 43 (53.8%) | 86 (53.8%) | |

| Age group | 1 | ||

| < 35 | 19 (23.8) | 38 (23.8) | |

| 35 - 45 | 14 (17.5) | 28 (17.5) | |

| 45 - 55 | 21 (26.3) | 42 (26.3) | |

| 55 - 65 | 14 (17.5) | 28 (17.5) | |

| 65 - 75 | 12 (15.0) | 24 (15.0) | |

| Marital status | 0.11 | ||

| Single | 9 (11.3) | 8 (5.0) | |

| Married | 67 (83.8) | 148 (92.5) | |

| Job | 0.38 | ||

| Employed | 11 (14.3) | 27 (17.1) | |

| Housewife | 29 (37.6) | 68 (43.0) | |

| Others | 37 (48.1) | 63 (39.9) | |

| Education level | 0.31 | ||

| Illiterate | 11 (13.8) | 17 (10.6) | |

| Undergraduate | 53 (66.2) | 93 (58.1) | |

| Postgraduate | 16 (20) | 50 (31.3) | |

| BMI | 0.69 | ||

| Normal | 43 (53.7) | 87 (54.6) | |

| Overweight | 29 (36.3) | 56 (35) | |

| Obese | 8 (10) | 17 (10.4) |

4.1. Association Between Diabetes and Hepatitis

In this study, 14 (5.8%) subjects had blood glucose levels of higher than 126 mg/dL twice, and were considered as diabetics. Among them, four (5.0%) of the case group (all having hepatitis B) and 10 (6.3%) of the control group were diabetics. The chi-square test results showed no significant difference in the incidence of diabetes between the two groups (P = 0.69, df = 1, χ2 = 0.15) (Table 2).

| Group No. (%) | Significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | All | ||

| Diabetes | χ2 = 0.15; df = 1; P = 0.69 | |||

| Positive | 4 (5.0) | 10 (6.3) | 14 (100.0) | |

| Negative | 76 (95.0) | 150 (93.8) | 226 (100.0) | |

| All | 80 (100) | 160 (100) | 240 (100.0) | |

Statistical analysis showed no significant difference between the mean serum lipids of cholesterol and LDL in both case and control groups, but there was a significant association between HDL and TG in both groups (Table 3). Statistical analysis showed no significant difference in the mean serum fasting blood glucose level in the first measurement between the case and control groups, but there was a significant difference between the two groups in the second measurement. Also, there was a significant difference in HbA1C between the two groups (Table 4).

| Group | Mean ± SD | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol | t = -1.82 P = 0.07 | |

| Control | 191.64 ± 36.76 | |

| Case | 182.24 ± 39.29 | |

| LDL | t = -0.86 P = 0.39 | |

| Control | 122.42 ± 34.65 | |

| Case | 118.43 ± 32.68 | |

| HDL | t = 2.05 P = 0.04 | |

| Control | 39.33 ± 7.60 | |

| Case | 41.86 ± 9.63 | |

| TG | t = -2.20 P = 0.02 | |

| Control | 155.34 ± 87.63 | |

| Case | 134.70 ± 56.47 |

| Group | Mean ± SD | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| FBS1 | t =-1.82 P = 0.07 δ = 9.01 ± 14.21 | |

| Control | 97.44 ± 30.71 | |

| Case | 106.45 ± 44.92 | |

| FBS2 | ||

| Control | 91.97 ± 36.00 | t = -4.12 P = 0.001 δ = 52.76 ± 11.83 |

| Case | 114.73 ± 47.83 | |

| HbA1C | t = -6.42 P = 0.01 δ = 0.98 ± 0.5 | |

| Control | 4.95 ± 0.96 | |

| Case | 5.93 ± 1.46 |

5. Discussion

Based on the statistical results obtained in this study, there was no significant difference in the frequency distribution of diabetes between the two groups. In a study conducted by Mekonenet et al. (2014) in Ethiopia on the prevalence of hepatitis B infection, there was no association between hepatitis B and diabetes (10). In a study conducted by Aziz (2000), no significant association was found between hepatitis B and C patients with fasting blood glucose and insulin resistance (17). According to the results of this study, diabetes was found in 13% of the patients with hepatitis B and C. In contrast to these results, other studies have suggested that the prevalence of diabetes in patients with HCV is higher than that in patients with HBV (18). However, the results of various studies differ because the population of patients studied in various research varied in terms of age, the severity of disease, having cirrhosis, and other factors that are considered as interfering factors in diabetes (18).

In contrast to the results of the current study, in a case-control study conducted by Memon et al. (2013) (18), the incidence of diabetes in patients with hepatitis C was significantly higher than that in the general population. Caronia et al. (19) and Ozylikan et al. (20) proved the high prevalence of diabetes mellitus in patients with hepatitis C.

Drakoulis (2002) and Chern (2001) showed that chronic hepatitis C infection could have a diabetogenic effect because hepatitis C increases liver damage caused by the accumulation of excess iron in the liver, and the developed liver dysfunction can be a factor in insulin resistance and impaired glucose tolerance (21, 22). A study conducted by Ebrahimzadeh in Esfandiare proved that the prevalence of HBsAg in diabetics was higher than that in non-diabetics (23). These differences can be due to the limited sample size of the current study and the differences in the race and geographical distribution or overall incidence of diabetes mellitus in each region, and also different demographic variables, and even the type of tests and kits. In the current study, the highest number of hepatitis was observed for hepatitis B (75 out of 80 cases were with hepatitis B virus).

There was no significant association between the prevalence of diabetes and age in the case group, while in the control group, this association was significant. Abdel-Aziz et al. (2000) also showed a statistically significant association between the incidence of type 2 diabetes and the age of the subjects (17). Contrary to the present study, the study by Liang et al. (2016) showed a higher prevalence of HbsAg in males (24). In the present study, there was no significant association between the prevalence of diabetes and marital status in each group, which is consistent with the study by Jadoon et al. (7). In contrast, in the study by Abdel-Aziz et al. (17), the prevalence of HCV in unmarried individuals was higher than that in married subjects. The results of this study revealed no significant association between the mean serum cholesterol and LDL lipids in both the case and control groups but there was a significant association between the two groups in terms of HDL and TG al. Alwan (2017) revealed a significant association between cholesterol and TG in HBV and HCV patients (4) but Sefidi found that in chronic hepatitis patients, total serum lipids were lower than those in the control group and with progression to end-stage liver disease, this decrease was more specific for cholesterol, LDL, and HDL (8).

In chronic liver diseases, serum lipids metabolism changes and serum lipoproteins decrease and return to normal level after transplantation (24). The difference in the results of the studies can be due to differences in the geographic regions' characteristics, and differences in dietary and physical activity and BMI, which are all effective factors in the serum lipid profile, which were not investigated in the studies. In the current study, the comparison of the mean HbA1c showed a significant difference between the two groups. Consistent with the present study, in the study conducted by Ebrahimzadeh in Esfandiar village, entitled the prevalence and risk factors for type 2 diabetes in hepatitis patients, mean HbA1c in patients with hepatitis B and diabetes was also significantly higher than those in non-diabetic hepatitis patients (22). Also, in a study conducted by Papatheodorid (2006), the mean HbA1c was also reported as a factor with a significant difference between the diabetic and non-diabetic groups in patients with hepatitis (25). It seems logical that the increase in HbA1c, which represents uncontrolled diabetes in patients with hepatitis, is higher in them than in healthy people and is a better factor than fasting blood sugar for hyperglycemia detection.

One of the limitations of our study was the high cost and scarcity of HbA1c kits, which we added to fasting blood sugar to confirm diabetes. The other case, fortunately, was the low prevalence of hepatitis C in the study population in Birjand, which reduced the sample size.

5.1. Conclusions

All patients with hepatitis B and C should be screened for diabetes, and in addition to fasting blood sugar, we suggest that HbA1c be measured to confirm or rule out diabetes. Considering that majority of the people with hepatitis are in the most effective age groups in communities, and considering the direct and indirect costs of diabetes and liver diseases for individuals and the healthcare system, the development of screening programs for these diseases is of utmost importance.