1. Background

Postpartum period induces mental and physical changes in women (1). Women may experience a wide range of mild to severe mental disorders in this period, including postpartum depression. Postpartum depression is a serious mental disorder and is one of the most important and common medical problems. Prevalence of postpartum depression was previously reported to range from 10% to 15%. The prevalence of postpartum depression has increased in recent decades. Based on the findings of a study, postpartum depression was observed in one out of four women (2). Postpartum depression can present as a combination of sadness, anhedonia, irritability, anger, and decreased self-esteem (3). It can occur due to maternal stress during pregnancy (3). Postpartum depression is due to the rapid drop in placental estrogen and progesterone after delivery, as well as disruption in hypothesis-pituitary-adrenal axis (4). This disruption results in reduced cortisone. Similarly, the sympathetic nervous system response to stress is also affected due to the rapid decline in the placental hormones. Furthermore, a reduced cerebrospinal concentration of gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) is also detected after delivery (4).

The complications of postpartum depression may involve both mother and newborn. Postpartum depression is also important due to its negative effects on social relationships and delay in the emotional contact between mother and newborn (2). Two common treatment options exist for postpartum depression, including antidepressants and psychotherapy. But women in postpartum period do not prefer medications due to the concerns regarding the side effects of drugs on breastfeeding (1, 5, 6). Antidepressants have not received attention from breastfeeding mothers due to their concerns about side effects on infants. Considering the complications of depression, including family relationship disturbances, family problems, postpartum depression may cause growth restriction in children, reduced attachment, and delayed mother-infant contact. Unlike psychotherapy that focuses only on improvements in psychological aspects of life, exercises during pregnancy can improve strength and energy and add to the benefits of psychotherapy. Exercise and physical activity have a crucial role in the improvement of disease symptoms (7). Even a low level of exercise can increase serum levels of serotonin, dopamine, and release of endorphins, which can improve postpartum depression (8). Various studies showed that different types of exercises were effective in reducing depressive symptoms in the elderly (9). Yoga is one of the recommended exercises for reducing depression (10). Yoga exercises can improve mood and affect (11).

Yoga is known to be among the top 10 complementary and alternative treatments for depression (12). Yoga exercises not only improve mild to moderate stress, anxiety, and depression but also can prevent these disorders (13). Various studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of Yoga in depression and anxiety in general population (14, 15). Yoga is an exercise that involves body and mind. Numerous studies have shown that Yoga was effective in decreasing depression and anxiety in general population (16-18). The mechanism of performing regular exercises in Yoga results in long-term sympathetic effects, changes hippocampal function, and prevents depression (19). A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials showed that Yoga practice may reduce cortisol, autonomic response (changes in heart rate and systolic blood pressure), cytokines, and lipid levels and, as a result, reduce stress symptoms (19). Yoga practice was found to have a positive effect on depression and anxiety symptoms in depressed pregnant women and was able to improve mood states in admitted psychiatric patients. Beneficial effects of Yoga on depression outcomes have also been reported in patients with major depressive disorder (19). Yoga is a physical activity that can reduce depressive symptoms in women with postpartum depression (20). In a study by Buttner et al. (2), depression, anxiety, wellbeing, and quality of life improved faster in women in the Yoga group compared to the control group. Previous studies proposed that pre-conception Yoga is a suitable method in the management of depression during pregnancy and that Yoga may be more acceptable than medication by pregnant women (21-23).

Although the majority of previous studies assessed the effects of Yoga on reducing depressive symptoms in postpartum period, there are few published articles on the preventive effects of Yoga during pregnancy on postpartum depression in healthy women (24). However, two systematic review and meta-analysis assessed the effect of yoga on anxiety and depression during pregnancy and prenatal periods before the year 2000 (14, 25). Satyapria et al. (26) suggested that Yoga practice before pregnancy is a suitable method for the management of depression in pregnancy. The majority of previous studies evaluated the effects of Yoga in specific periods of pregnancy or postpartum, mainly in women with a previous history of mild to moderate mood disorders. However, the preventive effects of Yoga on healthy pregnant women have not been fully evaluated.

Furthermore, only one meta-analysis was performed on the effects of Yoga on pregnancy in 2000.

2. Objectives

The present study was conducted with the aim of investigating the effects of performing Yoga in pregnancy and its preventive effect on Postpartum Depression.

3. Methods

This systematic review was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) checklist (27).

3.1. Paper Searching Strategy

The electronic databases, including PubMed, Google Scholar, Medlib, Scopus, Web of Science, Psych Info, and Cochrane Library were searched. Since previous systematic review papers on Yoga were published before the year 2000, the search time range was between 2000 and 2020. Moreover, the reference list of the identified papers was manually searched to find relevant papers.

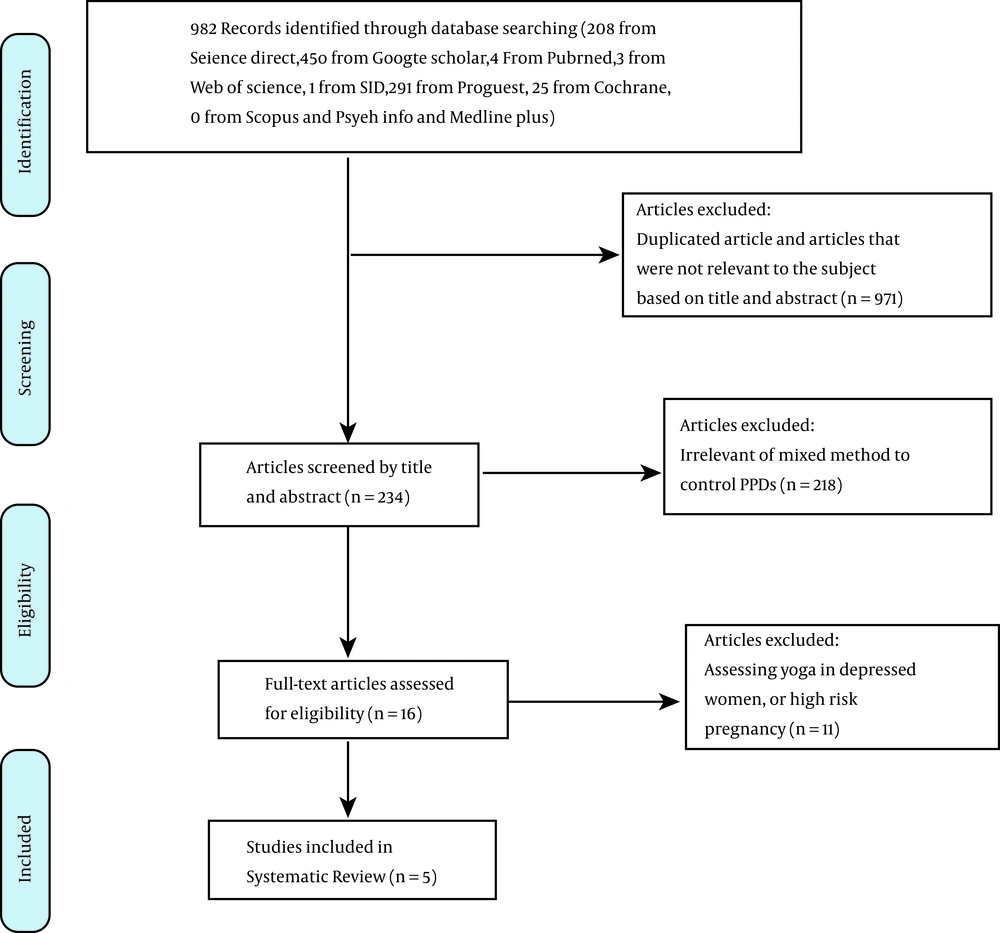

Search was performed in Peer-reviewed journals. Different combinations of the Boolean operators “AND”, “OR”, and “∗”, were utilized with the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) for search in PubMed. Search strategy was changed to search other databases using the following the keywords; “pregnant women”, “women”, “maternal period”, “yoga, mindfulness”, “postpartum depression”, “depression”. Modifications were made to search strategies for each database. The final search strategies are reviewed and approved in Figure 1.

3.2. Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were: papers in English language, randomized clinical trials (RCT), as well as studies conducted on healthy subjects with no history of depression. Studies that implemented Yoga, defined as postures, as an intervention were eligible for the review. Studies that included additional elements, including breathing, meditation, and relaxation, were included in the review. As these principles were the core principles in different types of Yoga, all types of Yoga that reported these principles were included. There was no restriction on the comparison groups and all studies that compared the effects of Yoga on postpartum depression were included.

3.3. Exclusion Criteria

Since the aim of this study was to assess the preventive effects of Yoga on postpartum depression in healthy women, studies on at-risk or high-risk pregnant women as well as women with the diagnosis of depression were excluded. Furthermore, non-randomized studies, irrelevant, studies with insufficient data, and papers investigating several sport methods simultaneously were excluded in the next stage of the review. The screening stages in the present study included title, abstract, and research question based on population, intervention, comparison, outcome, (PICO) criteria, and study design. Articles that were in line with the aim of this study and met the inclusion criteria based on PRISMA checklist were included in the review. The PRISMA flowchart of the screening and selection stages of this review is shown in Figure 1.

3.4. Data Extraction

Titles and abstracts were screened based on the population, intervention, comparison, outcome and study design (PICOS) and for inclusion criteria, by three researchers. In case of disagreements, a decision was made through conducting group discussions. SD and NS designed the search strategy in databases. Full texts of the eligible papers were reviewed by two authors (TFN and DA), and the study data were extracted. Two authors initially performed data extraction. The corresponding author re-checked data extraction for all included articles. The study procedure and manuscript writing were supervised by SD.

Screening for titles and abstracts resulted in the identification of 971 studies. A total of 234 articles remained after excluding duplicate studies (Figure 1). Then the full text of the selected papers was assessed. All of the selected clinical studies, based on the mentioned criteria, were analyzed, and data including title, authors, publication year, settings, sample size, participants’ age, and the main results, including the risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were recorded in a checklist according to predetermined criteria. Finally, seven papers were included for final investigating.

3.5. Quality Assessment

This review was performed based on the guidelines reported in the PRISMA statement. Quality assessment of the included studies was performed using the standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers (QUALSYST) (28). QUALSYST includes scoring systems for qualitative and quantitative research. QUALSYST includes eight domains, including study design and research question appropriateness; exposure and outcome determination; reporting bias, and confounders, as well as reporting results and study limitations. The scoring system is based on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (no) to 1 (partial), 2 (yes), and NA. The scores are summed to generate the overall score of the tool. Based on the recommended cut-off, articles that attained scores higher than 22 were considered to have acceptable quality (28). The methodological quality of papers was classified into low, medium, good, and high quality if the 14 QUALSYST criteria scores were < 50%, 50% - 69%, 70% - 79%, and > 80%, respectively (Table 1) (28). As no ethical approval was needed for conducting the systematic review based on Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, only university permission was obtained (29).

Abbreviations: N/A, not available; 0, No; 1, partial; 2, yes.

A standard form was designed to extract information from included studies. The extracted data included publication author(s) and year; country of origin, subject characteristics (sample size, maternal age, and gestational age [GA]); study design; conceptual framework; intervention; intervention provider; controlling the intervention; outcomes; and findings (28). The findings of the studies were synthesized using a narrative review instead of quantitative meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity in intervention approach, duration, length of follow-up, and outcome measures.

3.6. Data Analysis

Due to the substantial heterogeneity in study designs and outcomes, the initially planned meta-analysis could not be performed in this study.

4. Results

4.1. Study Quantity

Five articles were assessed for eligibility. The most common sources of bias were related to study protocols, using a mixed-method to control depression, unclear methodology, and inclusion of high-risk pregnancy in some studies. Characteristics of included studies are summarized in Table 2.

| Authors/Years of Publication | Country | Sample Size | Study Design | Theoretical Framework | Study Population Characteristics | Intervention | Control | Findings | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bershadsky et al. (30), 2014 | USA | 51 | Mixed within- and between-subject. | Controlled trial | 1) Older than 18 years old; 2) English speaking; 3) nulliparous; 4) Gestational age between 12 and 19 weeks; 5) no current diagnosis of depressive and/or anxiety disorders based on self-report. | Prenatal Hatha Yoga (90-min), asana (60 min) (body postures), stretching (10-min), and savasana (5 - 10 min) (final relaxation), and pranayama (breathing) | Routine prenatal care | Fewer postpartum depression symptoms in the Yoga group (P < 0.05). No change in antepartum depressive symptoms compared to the control group | Findings indicate that prenatal Hatha Yoga may; improve current mood and may be effective in reducing postpartum depressive symptoms. |

| Newham et al. (23), 2014 | UK | 59 | Two (groups) × two (time points) factorial design; Study duration was eight weeks | RCT* | 1) Healthy women (> 18 years old); 2) between second; or early third trimester; 3) uncomplicated singleton first pregnancy; (lasted more than 13 weeks); 4) higher levels of pregnancy-specific anxiety; 5) Gestational age of 20 weeks or 24 weeks) | Yoga intervention in three groups of 10 - 11 women. Hatha Yoga before birth and Bikram and Iinger after birth | Routine prenatal care | Pregnancy-specific anxiety (WDEQ score) was significantly lower in Yoga (P < 0.0001) and TAU groups (P = 0.04) after the intervention compared to baseline. | Practicing Yoga before birth reduces anxiety and preventing the onset of depressive symptoms. |

| Vieten and Astin (31), 2008 | USA | 31 | Randomized wait-list controlled trial | A mindfulness intervention based on MBSR intervention elements | 1) Between second and third trimesters; 2) gestational age between twelve and thirty weeks; 3) ability to read and write in English; 4) women with depression or anxiety; 5) Mean age of 33.9 | Eight-week mindfulness-based intervention directed toward Mindful Motherhood intervention | - | Anxiety and negative affect significantly reduced in the intervention group | Mindfulness based intervention during pregnancy could reduce negative affect and anxiety. |

| Satyapriya et al. (26), 2013 | India | 96 | Prospective randomized two-armed control | Prospective randomized control | 1) Gestational age between 18 and 20 weeks 2) prime gravid 3) multi gravid with at least one live child. | Specific set of integrated Yoga. Both groups learned the practices from trained instructors (3x2h/day sessions/week) for one month and continued the practices at home | Standard antenatal exercises. | Depression (HADS) reduced in Yoga (P < 0.001) with significant difference between groups (P < 0.001). | Yoga reduced anxiety, depression, and pregnancy related uncomfortable experiences. |

| Yazdanimehr et al. (32), 2016 | Iran | 80 | Single blind RCT | RCT* | 1) Gestational age between one and six months; 2) minimum high school education; 3) score of greater than 13 in the Edinburgh Depression scale and a score of greater than 16 in the Beck Anxiety Inventory; 4) no history of psychological disorders or chronic physical problems; 5) not receiving psychotherapy or drug therapy during the last six months; 6) depression and anxiety were not secondary to certain known causes (grief, marital conflict, divorce, or unwanted pregnancy) | MiCBT; mindful; breathing, step-by-step body scanning exercises, and awareness of visceral sensations; body scanning exercises, behavior therapy techniques (problem-solving), and interpersonal skills | Routine prenatal care | The mean anxiety and depression scores were significantly lower in the experimental group compared to the control group (P < 0.001). | Mindfulness-integrated cognitive behavior therapy can significantly improve depression and anxiety in pregnant women |

4.2. Summary of Quality Assessment

Table 1 shows the quality assessment of the articles using QUALSYST. Based on the evaluation performed, one study had medium quality (quality score = 60%) (31), one study had good quality (quality score = 75%) (30), and three studies had high quality( > 80%). (23, 26, 32).

4.3. Participants’ Features

Overall, the studies included 217 subjects. Sample size in the studies ranged from 20 to 96 subjects. The overall age range of the subjects was 15 - 35 years old. The ethnicity of the subjects varied between the studies. The gestational age for pregnant women who gave informed consent in the Yoga arm ranged between 6 and 24 weeks.

4.4. Intervention Characteristics

The reviewed studies used different interventions. The design of the reviewed studies was pre- and post-study, prospective, single blind, quasi-experimented, and pilot studies. One study was conducted in Iran, one in the UK, one in India, and two in the United States. All of the studies applied Yoga for physical and mindfulness exercises and breathing techniques.

In the study by Yazdanimehr et al. (32), a Mindfulness-Integrated Cognitive Behavioural therapy (MiCBT) program was administered in eight sessions, with each session lasting for 90 minutes. The intervention consisted of eight sessions, including a review of MiCBT (program structure and the materials), information about the essentials of concentration and breathing techniques, information about breathing awareness, physical exercises and awareness about visual sense, physical exercises and provided information on behavioral treatment techniques (including problem-solving techniques), the physical exercises, information on interpersonal skills, decisiveness and role play, information about acceptance and agony management in daily life, and assessment and evaluation.

In the study by Bershadsky et al. (30), 90-minute Yoga sessions were implemented with the focus on physical, mental, and breathing techniques for body situations, mental concentration, and body-mind relationship. Participants were evaluated five times during the study, at the beginning, and in mid-pregnancy, and once within two months after delivery. Evaluation was performed using health and behavior changes questionnaire (19).

In the study by Vieten and Astin (31), pregnant women received intervention on mental concentration, mental and sensual awareness through breathing awareness and reflective activities. Intervention included education, discussion, and experimental exercises. The intervention was based on self-awareness, including providing information about growing fetus and abdomen during meditation, stress about pain or sleep problems during pregnancy, anxiety about delivery, and problems in mindfulness. Sessions lasted for eight weeks, and the duration of the sessions was two hours (18).

In the study by Satyapriya et al. (26), the intervention included physical, mental, emotional, and mindfulness techniques for improving mental balance through breathing techniques and simple stretching exercises. These interventions improved vital capacity and vital energy equilibrium (26). In the study by Newham et al. (23), participants were divided into three groups (n = 10 - 11) for eight weeks. Each intervention session included Hatha Yoga and similar exercises, somatic position, and breathing techniques. But the intervention sessions were performed with the aim of assessing the effects of Yoga on pain relief in pregnancy (23).

5. Discussion

Vieten and Astin (31) showed that the intervention significantly decreased mean depression scores (from 20.4(8.4) to 16.2 (7.3)), while the mean depression score increased in the control group (from 14.2 (5.4) to 17.2 (7.4)) (P = 0.06). Bershadsky et al. (30) indicated that Hatha Yoga may improve mood in pregnant women before childbirth. The mean depression score in Yoga and control groups was 5.29 (3.14) and 4.54 (3.43), respectively at baseline and 3.92 (2.68) and 6.63 (2.83) in the postpartum period, respectively (P < 0.05) (30).

Newham et al. (23) showed that both yoga (P = 0.014) and usual treatment (P = 0.04) interventions significantly reduced pregnancy-specific depressive symptoms as compared to baseline (Mean difference = -0.76 (3.07)). The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression scale (EPDS) scores at follow-up were significantly higher in the control group. The observed increase in EPDS scores was significantly greater in the control group compared to the yoga group (2 [-1 to 4] Vs. 0[-3 to 2]) (23).

Satyapriya et al. (26) reported that Yoga resulted in a significant decrease in the hospital anxiety and depression score (HADS) (6.39 (2.55) to 4.43 (1.39)), while the HADS was increased in the control group (6.73 (2.22) to 6.98 (2.91)). It seems that HADS can better identify depressive symptoms compared to other similar tools (26). Depression was significantly improved in the Yoga group (P < 0.001), while no significant difference (P = 0.592) was observed in the control group (26). In the study by Yazdanimehr et al. (32), Yoga intervention resulted in significantly lower mean anxiety and depression scores compared to the control group (P < 0.001) (32). They reported that the HADS scores in depression in the control group changed from (16.63 (2.64) to 16.03 (2.45)) while it changed from 16.83 (2.7) to 9.03 (2.95) in the Yoga group (32).

Kmet et al. (28) concluded that the nature of Yoga is mastering mind and central nervous system and that, unlike other sports, Yoga has a moderating effect on internal neural function, hormone secretion, and physiologic factors, as well as regulating neural signaling. Many researchers hypothesized that Yoga affects nervous system, cardiovascular system, and genetic structure. It is hypothesized that Yoga exercises correct hypoactivity of the peripheral nervous system and GABA through vagus nerve stimulation and reducing the internal allostatic load; thus culminating the symptoms (24, 29, 31). Yoga also reduces cortisol hormone secretion, which is highly associated with stress in humans (30). Since yoga has a multidimensional effect on the body, its effects on psychological distress are comprehensive (32). The mechanism of Yoga in reducing serum cortisol levels is through the downregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (33). The therapeutic effects of Yoga-based practices have been reported in several psychiatric disorders. These mechanisms are believed to have positive effects on both healthy subjects and psychiatric patients (33).

All of the studies (five articles) reported depression was improved in the intervention group (26-30). Therefore, it seems that Yoga techniques can be used as complementary and alternative treatments for mental disorders (34). Some studies showed positive impact on Yoga in decreasing postpartum depression. Buttner et al. (2) showed that practicing Yoga during pregnancy resulted in more decrease in anxiety and depression scores and quality of life improvement compared to the control group. Beddoe et al. (35) showed that Yoga practice from 6th to 9th months gestation lowered the levels of stress and mental anxiety. Jakhar et al. (36) and Rakhshani et al. (37) showed that depression, anxiety subscales of the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) questionnaire improved faster in the Yoga group compared to the control group. Wilson suggested that teaching mindfulness during the pregnancy leads to a significant reduction in anxiety and negative outcomes (33). These results were consistent with the results of the present study. The results of the study by Sharma et al. showed that Yoga can reduce postpartum depression and suggested Yoga practice during pregnancy to reduce the effects of pregnancy events on mood (38).

An important limitation of this study was excluding articles that were not published in English language. Also, failure to performing meta-analysis can be considered a limitation. However, since different researchers used different questionnaires to assess depression, combining the findings of these questionnaires was not possible. This can affect the final interpretation of the study findings. Limitations of the reviewed studies included lack of consistency in sample size, type of Yoga administration, duration, follow-up, and study participants, which prevented us from performing meta-analysis. The strengths of this review included originality, extensive search strategy, using reliable quality assessment tools, and performing measures to reduce bias (e.g., each stage of the review was undertaken by at least three authors).

6. Conclusions

Yoga may significantly reduce postpartum depression in healthy pregnant women. Therefore, it is recommended that Yoga should be used as a strong and effective means to reduce depression in healthy pregnant women. It is suggested that future studies be performed to investigate the effect of this intervention on maternal mood changes during pregnancy. These findings indicated that Yoga is a feasible, safe, and acceptable intervention for pregnant women with signs of depression and anxiety. Although medication and cognitive therapies were effective in the treatment of major depressive disorders, these methods were less effective in milder levels of depression. Furthermore, these therapies are time-consuming, expensive, and may have side effects; therefore, there is a need for developing non-medical therapies for different levels of depressive disorder. Nowadays, exercise and physical activity are regarded as therapeutic methods for such disorders.

This review showed that currently available studies were heterogeneous, and therefore, no meta-analysis could be performed on the extracted data. Therefore, there is a need for further studies before reaching a recommendation.