1. Background

Gynecological cancers are the fourth most common malignancy in the female population (1). According to the American Cancer Society, 100,000 new cases of gynecological cancers were reported in 2019 (2). In Iran, in 2018, the incidence of gynecological cancers in women was 10.2 per 10000 people (2). Uterine cancer is the most common one (53%), followed by ovarian (25%) and cervical (14%) cancers; vaginal and vulvar cancers and neoplastic forms such as trophoblastic tumors are diagnosed less frequently (3-7). A range of site-specific difficulties can persist after care, including sexual challenges (12%), bladder dysfunction (11%), vaginal problems (e.g., recurrent infections) (10%), and limb lymphedema (10%) (8, 9).

With the exception of ovarian cancer, most gynecological cancer diagnoses are associated with moderate survival rates; the five-year survival rates for cervical, endometrial, and ovarian cancers are 75%, 83%, and 55%, respectively (10). Approximately 21% of women diagnosed with gynecological cancers are under 45 years of age and are of childbearing age. Furthermore, childbearing is increasingly delayed and for this reason, an increasing number of women are diagnosed with cancer before their first pregnancy (11).

Relational and sexual problems are frequent in women with a diagnosis of gynecological cancer, because this cancer has a strong adverse impact on the female identity and threatens the perception of own sexuality (3, 12). Psychological and sexual functions are affected by inauspicious diagnosis. Moreover, therapies of these tumors have a serious impact on sexuality and fertility, influencing the psychosexual balance of these woman as well as their body image perception (3, 13, 14). This issue becomes more significant in societies such as Iran, where women are the pillar of the family and society (15). Complex diseases, such as cancer, negatively affect the psychological, emotional, and physical dimensions of women along with their roles in the family (16, 17). Furthermore, the negative side effects of treatments on fertility are another challenge for the marital life of these women (18, 19). Another challenge in the marital life of these patients is the way that their husbands think about them as a “patient” or a “child”, not as a marital partner. These challenges cause unpleasant impacts on these women’s marital relations (20). There have been several studies about the medical aspects of these cancers, but few have investigated the marital problems of these patients.

It is worth noting that quantitative studies cannot cover the deep aspects of subjects’ experiences. Qualitative studies focus on the lived experiences of the individuals, and the most principal matter is that these experiences are revealed through the cultural and social background of the specific country (21). Therefore, it seems that understanding the experiences and challenges of women with gynecological cancers can help in determining the educational and counseling needs of these patients and their families, identifying the common challenges, problems and barriers, and recognizing facilitating factors. In doing so, the quality of care and support to these women and their husbands can be improved.

2. Objectives

In conclusion, the aim of this study was to explain the challenges in the marital life of women with gynecological cancers.

3. Methods

This was a qualitative study was extracted from a doctoral dissertation in Nursing with the code of ethics IR.BUMS.REC.1397.363. Using the purposive sampling method, 16 women with gynecological cancers from different referral centers in Mashhad city, Iran, were selected. To achieve maximum variation of participants (e.g., age, social and economic situation, the stage of disease, etc.), sampling was performed until reaching data saturation. Interviews were conducted whenever the patients were available.

The interviews were conducted in a quiet place such as a silent room in clinics or the head nurse room when it was allowed. The interviews were held without the presence of a third participant. The inclusion criteria were: (1) being diagnosed with gynecological cancers for six months, (2) living under the same roof with their husbands, (3) not having metastasis diagnosed based on medical records and the opinion of an oncologist, and (4) having the ability to participate in face-to-face interviews and speak fluent Persian. The exclusion criterion was unwillingness to continue the interview. Ethical considerations included obtaining permission from the ethics committees of Birjand and Mashhad universities of medical sciences, obtaining oral and written consent from the patients, and obtaining permission from the patients to record their voices and conducting individual interviews at the venue. Patients felt more comfortable and secure in expressing their experiences by assigning separate codes to each patient instead of mentioning their names.

After explaining the purpose of the study and obtaining written and oral consent, semi-structured and in-depth interviews were conducted with the participants. The interviewer was a PhD candidate in Nursing, and since she was a woman, the participants felt comfortable to share their sexual and marital experiences.

The participants were asked to talk about their "Marital life after gynecological cancer" to begin the interview. Then, according to the purpose of the research, they were asked about their worries, challenges and problems of marital life after being diagnosed with this disease. In other words, the interviews were initiated with general questions and the subsequent questions were based on the concepts extracted from the initial answers. Also, follow-up questions such as "Please explain more about this issue" were used to encourage the patients to further explain the issue. In addition to recording the interviews with an MP3 player, observation, field notes, and memos were used by the researcher. Each interview lasted about 40 minutes (30 - 60 minutes). The verbatim transcript of each interview was coded, and after analyzing each interview, the next interview was conducted. To manage the coding process, MAXQDA version 18 was used. Data were analyzed by the conventional content analysis method.

3.1. Trustworthiness of the Study

Lincoln and Guba criteria include (credibility), transferability and fittingness, conformability, and dependability for data accuracy (22). For ensuring creditability, the authors had a long-term engagement with the participants in this study. Furthermore, the study team, showed the encoded interviews to the patients to check if the codes are in line with their experiences. Moreover, all the concepts were investigated by experts during the study. Dependability was approved with a sample of women that had a rich experience in marital life after these types of cancer. Confirmability was approved through comparing the results with other studies on this issue. Also, by selecting the widest diversity of patients with gynecological cancers, the authors tried to establish the transferability of the study, and the authors carefully explained the method of the study for future studies and researchers (23).

4. Results

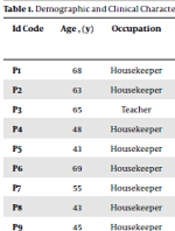

A total of 16 women with gynecological cancers were interviewed. The age of these women ranged from 35 to 62 years (mean: 53.4 ± 8.2 years), and their level of education spanned from fifth grade to master's degree. The duration of gynecological cancer was 1 - 10 years (mean: 2.88 ± 2.27 years). In addition, 37% of these women had uterine cancer, 38% had cervical cancer, and 25% had ovarian cancer (Table 1). The three themes emerged from these women's experiences related to the challenges of gynecological cancer included: (1) concerns about losing their position in marital life (forcing to stop sexual intercourse, increasing the burden of life on the spouse, and reducing the patient's presence in marital life), (2) effect of the disease on sexual relations (deterioration of intimacy, unpleasant experiences during sexual intercourse, and the occurrence of gradual sexual frigidity), and (3) concerns about the possibility of divorce and separation (being out of favor with husband and marital conflicts) (Table 2).

| Id Code | Age , (y) | Occupation | Type Of Genital Cancer | No. Of Child | Time Elapsed from Diagnosis the Cancer(y) | Current Treatment | Husband’s Occupation | Husband’s Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 68 | Housekeeper | Cervix | 1 | 5 | Hysterectomy | Employed | 70 |

| P2 | 63 | Housekeeper | Cervix | 4 | 2 | Follow up | Farmer | 68 |

| P3 | 65 | Teacher | Cervix | 3 | 2 | B.T | Military | 75 |

| P4 | 48 | Housekeeper | Uterus | 3 | 1 | B.T | Businessman | 56 |

| P5 | 43 | Housekeeper | Uterus | 4 | 2 | B.T | Unemployed | 53 |

| P6 | 69 | Housekeeper | Uterus | 6 | 1 | B.T | Military | 77 |

| P7 | 55 | Housekeeper | Ovary | 4 | 2 | Follow up | Driver | 69 |

| P8 | 43 | Housekeeper | Cervix | 4 | 3 | Follow up | Farmer | 59 |

| P9 | 45 | Housekeeper | Uterus | 6 | 3 | Follow up | Employed | 58 |

| P10 | 41 | Housekeeper | Uterus | 2 | 3 | B.T | Military | 45 |

| P11 | 52 | Teacher | Cervix | 3 | 1 | B.T | Teacher | 62 |

| P12 | 64 | Housekeeper | Uterus | 6 | 10 | Follow up | Employed | 70 |

| P13 | 72 | Housekeeper | Cervix | 6 | 5 | Follow up | Farmer | 76 |

| P14 | 23 | Housekeeper | Ovary | 2 | 1 | Follow up | Manual worker | 25 |

| P15 | 44 | Teacher | Ovary | 3 | 2 | Follow up | Teacher | 52 |

| P16 | 48 | Housekeeper | Uterus | 6 | 3 | Follow up | Farmer | 50 |

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Participants (N = 16)

| Major Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Concerns about losing their position in marital life | Forcing to stop sexual intercourse |

| Increasing the burden of life on the spouse | |

| Reducing the patient's presence in marital life | |

| Effect of the disease on sexual relations | Deterioration of intimacy |

| Unpleasant experiences during sexual intercourse | |

| The occurrence of gradual sexual frigidity | |

| Concerns about the possibility of divorce and separation | Being out of favor with husband |

| Marital conflicts |

Themes and Subthemes

4.1. Concerns about Losing their Position in Marital Life

Gynecological cancers had affected the patients’ lives in several ways, and in fact, it was a serious threat to their current status in marital life. Thus, these women could not have sexual relations with their husbands and were forced to stop having sexual intercourse.

As stated by one of the participants: “The first time I went to the doctor. and took my tests and documents ... the first thing she said was that I should not have sex with my husband at all I said to myself at that time, well, how dangerous is this disease?" (Partner No. 4).

In addition to challenge in sexual relationships, the chronic and long-term process of the disease had disrupted the main roles of the patients as a mother or wife in the house. The shift of performing these duties to the husband and his involvement in these matters had increased the burden of life on their shoulders, which was one of the concerns of the patients.

In this regard, one of the patients stated:

"My poor husband, goes to garden on his own Previously, I used to get up early and do a series of things ... I prepared lunch and tea... now my poor husband does all these things by himself... he tells me not to do anything, just rest, I will come home in the evening to do the housework… oh, my husband had not poured me a glass of tea until now ... my poor husband comes in the evening, tired and exhausted ... he cooks dinner and does anything he can ..." (Participant No. 3).

4.2. Effect of the Disease on Sexual Relations

Gynecological cancer had caused a gradual deterioration in sexual relations between patients and their husbands, and it had become a major concern for the patients. One of the examples of marital communication disorders in these patients and their spouses was the deterioration of marital intimacy.

Men also avoided expressing intimacy when the patients needed more intimacy from their spouses. In this regard, one of the patients stated:

"Ever since I got sick, his behavior has changed in every way I feel that he is no longer interested in me... He has left me ‘I do not care at all ... I do not care about my condition’ . It seems that he likes me not to be at home at all ... now that I prefer to be with him, he stays away from me ... he has become unfeeling " (Participant No. 9).

Participants also reported feeling sexually assaulted because they were forced to have sex without desire. Some participants stated that this behavior of their spouses in forcing them to have sex will never be forgotten and will always remain in their memory as a bitter experience.

In this regard, one of the participants stated:

"I have to answer my husband’s sexual needs. but I have no feelings, I hate it as if a stranger wants to have sex with me … I hate it and I feel tormented " (Participant No. 15).

Concern about the possibility of divorce and separation

Concern about the possibility of divorce was gradually increased among these women, because as mentioned before, the patients could not do their routine roles and responsibilities as a wife and mother. Furthermore, some husbands complained about the situation. In this regard, some patients felt that they had lost sight of their husbands in such a way that they felt overwhelmed and useless in life.

In this regard, one of the patients stated:

“. Believe me or not, I feel like an extra sick person who needs her husband and children ... I'm so upset I cannot cook dinner and lunch for them ...” (Participant No. 5).

The participants also reported a gradual decrease in financial and emotional support from their spouses. In fact, the level of tolerance of the spouses regarding this situation by had reduced, leading to decrease in their financial and psychological support; thus, the patients felt unhappy about this situation. In this regard, one of the patients stated:

“My husband has changed a lot ... It's not like the first time he comes with me for my treatment ... now he says I'm getting a taxi for you ... he means go and do not return ...” (crying) (participant No. 2).

"We were angry with each other... The situation is very obvious ... My husband started a small fight and went to his friend's house. He slept there one night... Well, one night I went to my father's house ... Whatever he said ... I said nothing ... " (Participant No. 5).

5. Discussion

The aim of this study was to explain women's experience of the challenges of gynecological cancers. The first theme of this study was "concerns about losing their position in marital life (forcing to stop sexual intercourse, increasing the burden of life on the spouse and reducing the patient's presence in marital life)." Abadi et al., who studied women's experiences of sexual intercourse after hysterectomy in Iran, also reported women’s concerns about the possibility of remarriage of their husbands due to their inability to meet their sexual needs (24).

Another concern of these patients was regarding their reduced presence in life. Studies have shown that suffering from the disease, worries about the future of family members, and fear of death can lead cancer patients to be depressed (15, 25). Thus, depression gradually prevents them from any constructive activity, especially performing the marital and the motherhood responsibilities (16). Subsequently, decrease in their daily activities at home was perceived and challenged by family members in a very tangible way.

The second theme that emerged in this study was "Effect of the disease on sexual relations (deterioration of intimacy, unpleasant experiences during sexual intercourse and the occurrence of gradual sexual frigidity)." The decline of marital intimacy is one of the important findings in this regard. In fact, as the illness worsened, women thought that their husbands did not have deep intimate feelings toward them as they had before . In a study that examined the relationship between women with gynecological cancers and their husbands, the reasons for the decrease in marital intimacy by husbands of these women were the presence of mental and physical stress, chronic fatigue, and high levels of anxiety and unpleasant feelings in them (17).

Unpleasant experiences during sexual intercourse was another issue raised by the participants. Anxiety during sex was one of them. Due to the side effects of treatment, in many cases, vaginal intercourse was not possible for the spouses of these patients during sexual intercourse due to excessive vaginal tightness and contraction. Therefore, sexual intercourse was stopped and the husbands of these patients began to complain about the situation. This challenge was repeated in subsequent sexual intercourses, and thus became a factor in creating anxiety and stress for patients during intercourse.

Feeling sexually abused was another important finding of this study. The participants stated that their spouses were not willing to give up sexual intercourse in any way and forced them to have sex without considering the patients' physical and mental conditions and their readiness and satisfaction. In this case, the patients felt like having sex with a stranger. Forcing women into having sex has been also reported in some other studies (26-29). In some patients, hysterectomy was a factor in reducing their husbands' sense of femininity. Many participants stated that their spouses were reluctant to have sex with them after a hysterectomy and felt that their spouses had lost their sexual desire and that sex was not pleasurable. In a study examining women's sexual experiences after hysterectomy, a reduction in marital intimacy by the husband was also reported due to not having a uterus (24).

Another finding of this study was patients' attempts to shy away from intercourse and intimacy with their spouses. One of the cases was the violent reaction of patients to their spouses' offer to have sex. Also, some patients scared their spouses from having sex. Shirin Kam et al., who studied sexual intercourse in women after hysterectomy, also reported patients escaping from sexual intercourse with their husbands (30).

Another study in Morocco found that women with gynecological cancer sought excuses and ways to avoid having sex with their husbands (31). It seems that the attempt to escape from intimacy in patients in the present study was on the one hand due to fear of recurrence of the disease in case of vaginal intercourse, and on the other hand, owing to the reluctance of these patients to re-experience the tragic events during intimacy that were mentioned earlier.

The third category of the results of this study was "concerns about the possibility of divorce and separation (being out of favor with husband and marital conflicts)." Studies have shown that patients with cancer face numerous challenges in their marital life such as divorce, and in fact their illness has a more negative impact on their marital life than they expected (32, 33). On the other hand, it has been found that women are more likely to get divorced when diagnosed with cancer than men (34).

In this regard, a study in Sweden, which was conducted among cancer patients, showed that women with breast cancer were at a greater risk to get divorced, while men with prostate cancer were less likely to do so (35). In the present study, reduced closeness of patients' husbands to them was one of the possible causes of divorce. Various studies that have examined the effect of cancer on women and its relationship with marital relationships have reported the negative effect of increasing emotional and financial burden of cancer on couples (32, 36, 37).

5.1. Conclusion

Women with gynecological cancers face challenges such as worrying about losing their place in marital life deterioration of intimacy, and the possibility of divorce and separation. These women need more support and education in these regards, and it seems that in addition to informing healthcare providers about the problems and challenges of these women, holding training courses for these patients and supporting them can be advantageous. Finally, further studies are needed to provide practical solutions to the challenges of women with gynecological cancers to improve their physical and mental health.