1. Background

Communication in nursing is a vital element in all areas, including prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation, education, and health promotion (1). Communication with nurses is among the most significant concerns of hospitalized cancer patients. On the other hand, the maintenance of the patient’s peace is the best care that is achieved in the first place by winning the patient’s trust by the nurse. This goal also requires proper communication, imparting beneficial information to patients, showing affection, and nurturing hope in patients by converting their negative emotions and moods to positive and promising ones (2).

Establishing good relationships with patients, especially cancer patients, is critically essential for nurses and health care providers (3). Particularly, nurses have a more important role in creating appropriate relationships with patients and their families than have other members of the medical team. Neglecting communication principles, the lack of empathy skills, poor inter-professional communication, low skills in providing palliative care, ignoring patients’ cultural backgrounds, and the lack of organizational support will lead to unilateral communications and solely the provision of routine nursing care (4-6). Therefore, considering the critical prominence of the interaction between oncology nurses and patients and their families, oncology nurses must be equipped with proper communication skills to be able to deliver effective care services (6). An appropriate relationship increases the trust and satisfaction of patients and their families, improving treatment outcomes (7). As cancer patients are repeatedly hospitalized during the disease course, nurses have greater opportunities for building a relationship and gain the trust of patients by supporting them and their families. Nurses also play crucial roles in the psychosocial support and care of cancer patients (8). Proper communication with cancer patients is indispensable for involving them during the decision-making process regarding care provision and preventing the adverse effects of cancer treatment (9).

Despite the numerous advantages that an effective relationship between nurses and patients can have, oncology nurses report countless challenges during building such a relationship in practice. In a study by Lotfi et al., the challenges of dealing with aggressive patients and those who had concerns and worries about death were reported as common barriers by oncology nurses (3). Another study by Norouzinia et al. indicated that nurses and other health care workers had insufficient skills in properly communicating with patients (10). Lotfi et al. also reported poor communication between nurses and patients (3). Nurses’ communication behaviors can vary in different contexts (11). McCormarck believes that the nature of the nurse relationship largely depends on the context of the nursing care provision environment (12).

Therefore, the novelty of the topic of communication is a function of the context and actually a subjective concept, and there is a need to delve deeper into the subject to determine communication challenges among oncology nurses to better understand the concept and help nurses to recruit advanced communication skills.

2. Objectives

This study was designed to explain the communication challenges of oncology nurses when providing care for cancer patients by employing a qualitative content analysis approach.

3. Methods

This qualitative study was conducted in 2021. Oncology nurses who had rich experiences on the study subject were enrolled. For this purpose, after making the necessary coordination with the respective authorities and obtaining the required permissions, 18 oncology nurses working in hospitals in the east and southeast regions of Iran (i.e., the Iran Mehr Hospital of Birjand and Khatam Al-Anbia and Ali-Ibn-Abi Talib hospitals of Zahedan) were selected via the purposive sampling method. The inclusion criteria were having at least two years of working experience in the Oncology Department and willingness to participate in the study. Those who were not inclined to participate or those who had incomplete interviews were excluded from the study.

In this study, semi-structured interviews were conducted and recorded using two digital audio recorders. Each interview was held in one or two 60 - 90-minute sessions. After obtaining written consent from the participants, interviews were conducted in various shifts (i.e., the morning, evening, and night shifts) in a solitary place in the oncology wards of the selected hospitals. At the beginning of the interviews, the study aims were explained to the participants, and then they were requested to describe their experiences in providing care for cancer patients. After that, according to the study objectives, the nurses were questioned about their concerns and communication challenges encountered when caring for cancer patients. Probing questions such as “Can you explain more?” and “What do you mean by that?” were asked subsequently. In the end, the participants were asked to share anything that they felt was untold. Next, each interview was entirely transcribed verbatim, and to ensure the accuracy of the transcribed text, the recorded audios were listened to again to be simultaneously matched with the written words. The data were simultaneously analyzed by the method proposed by Graneheim and Lundman (13).

According to the Granheim and Landman analytic method, the interviews were initially transcribed and reviewed several times in order to reach a complete understanding of the entire text. Next, the meaning units were extracted and then classified as compressed units. Then, the compressed units were summarized, classified, and labeled with semantic tags. The next step was the sorting of subcategories based on their similarities and differences. Finally, appropriate titles covering all the emerged categories were selected. For better data management, MAXQDA software (2020) was used. After conducting 18 interviews, data saturation reached, after which no new categories and themes emerged.

In order to ensure rigour and trustworthiness, the trustworthiness criteria proposed by Lincoln and Guba were used (14). The credibility of the data was ensured based on the member checking approach, immersion, and the researchers’ prolonged engagement with the data. Peer-checking was employed to ensure the confirmability of the data, during which experts with experience in qualitative research methodologies were asked to assess the interviews, initial codes, and categories extracted, followed by repeating reviews. For the dependability of the data, all the steps of the research were recorded step-by-step and reported as accurately as possible.

All ethical considerations were observed, and the participants were free to discontinue the interviews at any time without worry about any ensuing problem.

4. Results

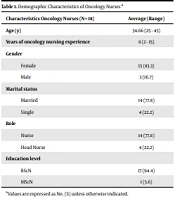

Data analysis revealed 30 subcategories, eight categories, and four themes. The themes included the nurses’ close relationship with cancer patients as a double-edged sword, curvy and sinusoidal professional communication for oncology nurses, relationship with an opposite-gender patient as a missing factor in nursing care, and marginalization of relationships during the coronavirus pandemic. Table 1 displays the demographic characteristics of the participants, and Table 2 demonstrates the categories and themes extracted.

| Characteristics Oncology Nurses (N= 18) | Values |

|---|---|

| Age (y), average (range) | 34.66 (25 - 45) |

| Years of oncology nursing experience, average (range) | 8 (2 - 15) |

| Gender, No. (%) | |

| Female | 15 (83.3) |

| Male | 3 (16.7) |

| Marital status, No. (%) | |

| Married | 14 (77.8) |

| Single | 4 (22.2) |

| Role, No. (%) | |

| Nurse | 14 (77.8) |

| Head Nurse | 4 (22.2) |

| Education level, No. (%) | |

| BScN | 17 (94.4) |

| MScN | 1 (5.6) |

| Themes | Categories |

|---|---|

| Nurses’ close relationship with cancer patients as a double-edged sword | The formation of a close relationship between nurses and patients |

| Behavioral abnormalities in patient-nurse communications | |

| Curvy and sinusoidal professional communication for oncology nurses | Efficient professional communications |

| Professional communication threats | |

| Relationship with an opposite-gender patient as a missing factor in nursing care | Male oncology nurses’ communication challenges |

| Patients’ more trust in the same-gender nurses | |

| Marginalization of relationships during the coronavirus pandemic | Weakening of communications with patients |

| The disheartening of nurse-patient communications during the pandemic |

4.1. Theme No. 1: Nurses’ Close Relationship with Cancer Patients as a Double-edged Sword

Regarding the oncology nurses’ perspectives, most of them admitted the formation of a close relationship between nurses and patients in the Oncology Department and the existence of behavioral abnormalities in patient-nurse communications.

Regarding the formation of a close relationship between nurses and patients, the participants believed that the small environment of the Oncology Ward and the small number of patients are the factors causing nurses to spend extended periods of time with patients. Also, repeated visits and hospitalizations lead to the formation of this relationship by boosting nurses’ acquaintance with patients.

One of the nurses working in the Oncology Ward stated: “...Our patients generally visit the ward repeatedly…our patients have at least six treatment sessions, and some of them are coming for five or six years and sometimes continue to receive palliative care and therapy for the rest of their lives. During specific periods, for example, every 21 days, the patient comes to us to receive medications… I mean we come to know each other pretty well…sometimes leading to a familial form and closer relationships….” Participant No. 6

Another participant said: “... the relationship has been so close during the eight-year period I've been here, I’ve met patients and get acquainted with them so much so that they outnumbered the number of my relatives in my own city... because the environment is small; the number of patients is limited, so respective to big cities, patients, either hospitalized or outpatients, all know each other here….” Participant No. 4

Some participants mentioned some behavioral abnormalities in patient-nurse communications, including patients’ increased expectations because of the close relationship, confrontations and guarding of some cancer patients, patients’ unjustified expectations from nurses, and harms to nurses and patients because of the close relationship. The following is the statements of a nurse working in the Oncology Ward:

“Sometimes because of the bilateral emotional relationship formed with the patient, patients’ and their companions’ expectations grow…but in other hospital wards, for example, a patient comes once or twice, and then nurses and patients do not see each other, but this is not the case here...” Participant No. 6

Another participant acknowledged that “...because some patients visit here repeatedly, and their companions see that we have a close relationship with their patient, they may let themselves to have unjustified expectations and demands…for example, a patient with urinary incontinence expected us to change his diaper…you can’t tell them no...” Participant No. 8

The following are statements by other participants: “…because of this close relationship with the patients, some of them quickly guard against us and behave aggressively...” Participant No. 3 and “... A bond is formed, either way; patients come and go…you see some of them heading towards the end of their lives…so this close relationship sometimes bothers you…” Participant No. 18

4.2. Theme No. 2: Curvy and Sinusoidal Professional Communications for Oncology Nurses

According to the experiences of oncology nurses, nurses did not experience a uniform pattern in professional communication. In fact, the pattern of this relationship was curvy and sinusoidal, which was sometimes experienced as a threatening and sometimes very friendly professional relationship.

Two categories of efficient professional communications and professional communication threats emerged under this theme. Regarding the efficient professional communications category, the subcategories included the nurse’s easy access to the doctor, intimate attitude towards the ward’s doctors, the empathetic relationship between nurses, and friendly behaviors among nurses. The following are excerpts from the participants’ statements in this regard:

“...We are very intimate with our ward’s doctors. I personally have never had a problem with our doctors… and we have not had any problems with them about anything, for example, any explanation about the patient’s care process and treatment....” Participant No. 9

“... Our ward’s doctors, both of whom are female, Dr. S and Dr. R, are very good doctors. I mean… they treat the children with much kindness. For instance, once on a busy day, a patient had come from Baluchestan, and she did not let the patient go without a visit ...she called us to see if there was an empty bed …and we did our best to sort it out…” Participant No. 11

“... Our relationship is very friendly, both the supervisor and our other colleagues all understand each other in some way. This understanding itself makes bearing the problems much easier...” Participant No. 17

“… compared to other wards, colleagues here are much more intimate with each other, we spend time with each other outside the hospital…” Participant No. 10

The category of professional communication threats consisted of the subcategories of challenges in the nurse-doctor relationship, some physicians neglecting nurses while visiting patients, and tensions in the relationship between nurses and supervisors. The following are some of the participants’ statements:

“... Our head nurse gives more attention to some nurses. For example, we have a nurse with 10 years of work experience who has to do many shifts, but a nurse with seven years of work experience, who does fewer shifts… our new supervisor somehow shows discrimination in communication with nurses...” Participant No. 7

“…If I did not have this problem with the hospital’s authorities, I would not like to change my ward at all. I was very satisfied with my job, and I really loved to work in the Oncology Ward, but unfortunately, my superior did not support me and my nurses…” Participant No. 1

4.3. Theme No. 3: Communication with Opposite Gender Patients as a Missing Factor in Nursing

According to the participants’ statements, male nurses working in the Oncology Ward had several communication challenges. It was also stated that patients tended to have more trust in the same-gender nurses. These two categories formed the current theme.

Regarding the communication challenges of male nurses working in the Oncology Ward, the analysis of the participants’ interviews revealed the subcategories of the white coat syndrome disrupting the communication between sick children and male nurses, more willingness of children with cancer for female nurses, some female patients not communicating with male nurses, male nurses’ lack of empathy, and cultural barriers in male nurses’ communications. One of the oncology nurses addressed this issue as: “… To my opinion, the most difficult part for male oncology nurses is to establish a relationship with ill children and female patients. It is hard for me to communicate with children... it is hard; I really can’t do it…” Participant No. 7

Another participant said:” …Men are more rigid in their relationships because all they have is their pride. A man should be strong and proud...” Participant No. 5

Other participants also stated: “... for us, men, it can be said that we are somehow thick-skinned. I believe that the psychological aspect of communication is less important. For example, it is hard for us to empathize with the patient… in close relationships, female nurses are more affected…” Participant No. 7

"…For getting IV lines, well, female patients are much more sensitive ... this is because of their cultural background ... It had happened to me when I intended to puncture a female patient’s vein, but she did not allow me and asked for a female nurse… .” Participant No. 6

Some participants reported the tendency of female patients for female nurses to perform invasive procedures, insisting on receiving care from the same-gender nurses, and patients being more comfortable to establish verbal communication with the same-gender nurses. The following is the statement by one of the participants: “... Female patients are like this, if I want to take a blood sample, they say no, please send a female nurse, they trust in female nurses for vein puncture and other procedures more than in men…” Participant No. 7

“…Well, most of our patients prefer to communicate with the same-gender nurses ... male patients become more accustomed to male nurses, and female patients like to speak to female nurses and prefer communicating with them... Unfortunately, we do not have male nurses at the moment, they have been here before but have left for other wards, and this is a challenge for us….” Participant No. 18

4.4. Theme No. 4: Marginalization of Communications in the Shadow of the Coronavirus Outbreak

As our study was performed during the COVID-19 pandemic, one of the challenges experienced by oncology nurses (the fourth theme) was the marginalization of communications in the shadow of the coronavirus outbreak. Most participants acknowledged the weakening and disheartening of nurse-patient relationships during this time.

The category of the weakening of the nurse-patient relationship during the coronavirus outbreak consisted of the subcategories of avoiding patients during the outbreak, keeping distance from patients, not allowing patients’ companions to enter the ward, and separating patients due to the coronavirus pandemic. The following are excerpts from the participants’ statements in this regard:

“… Well, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been here for a while now, our patients have to remain in their homes…their mental health has been damaged…their communications have been limited…they are not allowed to bring companions to the ward…and they are alone in their rooms…” Participant No. 10, “... It has become hard for us during the coronavirus pandemic … communications are not face-to-face anymore, and our relationships with patients have been reduced ... ..” Participant No. 13, “… A week after I was in contact with a patient, I got the coronavirus disease … afterward, I was becoming distressed when I approached patients … we would give them a series of recommendations to sit apart from each other and advise colleagues to not get too close to patients ...” Participant No. 12

Regarding the patient-nurse relationship becoming disheartened and cold, the subcategories included the shadow of fear in communications and limiting communications to the care provision time. These notions emerged in the participants’ statements as follows: “...Before the COVID-19 pandemic, we used to change the mood of our patients ourselves for example by a small celebration party…we used to throw parties a lot…but during the coronavirus pandemic, there is nothing we can do, not even a small party …” Participant No. 18

“...We had a patient who was hospitalized for a month. Two weeks later, we realized that he tested positive for the COVID-19. Our colleagues did not wear any protective clothes when they sent the patient’s sample. The stress of getting infected by patients exists, so we go to patients’ rooms less frequently since then ...” Participant No. 7

“.... COVID-19 has affected communications to a great extent. We always have to wear a face mask coming in or going out…you cannot see anybody’s face … and should always be alert for observing health instructions ...” Participant No. 14

5. Discussion

The findings of this study revealed four themes, including nurses’ close relationship with cancer patients as a double-edged sword, curvy and sinusoidal professional communication skills of an oncology nurse, relationship with an opposite-gender patient as a missing factor in nursing care, and marginalization of relationships during the coronavirus pandemic.

Regarding the first theme, the analysis of the participants’ views showed that close nurse-patient relationships formed due to more acquaintance with patients because of the small size of the ward, the limited number of patients, and patients’ frequent referrals and hospitalizations. In parallel, Pakpour also explained that small ward environments and the limited number of nursing and medical personnel could lead to a longer and more intimate relationship between members (15). This finding is consistent with the conditions of oncology departments in the studied cities.

According to the participants’ experiences, the category of behavioral abnormalities in the relationship between patients and nurses consisted of the subcategories of patients’ unjustified expectations and increased expectations. In agreement with these observations, Samant et al. revealed that patients hospitalized in oncology wards due to their special mental conditions are more sensitive to non-verbal communications with nurses and have higher expectations than other patients (16). In this regard, the participating nurses emphasized the abnormalities in the relationship due to the patient's factors and characteristics, including the close relationship between the patient and the nurse, and expressed it in various ways.

Among other experiences of the participants was some cancer patients’ defensiveness in their relationships with nurses. Consistent with this finding, Chapman et al. also stated that due to the special condition and emotional and psychological instability of patients and families, as well as pressures from various sources, cancer patients may show aggressive behaviors towards nurses (17). Afriyie also acknowledged that the observance of boundaries and intimacy and preserving privacy and hierarchy in relationships while performing professional duties are pillars in organizational communications (18).

The second theme was curvy and sinusoidal professional communications of oncology nurses, comprising efficient, professional communications and professional communications' threats categories. Under the category of efficient, professional communications, there were the subcategories of the nurse's easy access to the doctor, intimate attitude towards the ward's doctors, empathetic relationships between nurses, and friendly behaviors among nurses. In the same vein, Pakpour et al. also identified that being respectful toward nurses and performing therapeutic procedures as a team would improve communications between personnel (15).

Hitawala et al., in their study, reported nurses' higher satisfaction when physicians adopted respectful methods in communication with them (19), which was in line with the findings of the present study, highlighting the necessity of employing appropriate communication skills by both nurses and physicians. Communication experience from the perspective of nurses participating in this study showed the effectiveness of communication, and this perception was due to the experience of collaborative and team relationships between nurses and physicians.

The category of professional communications’ threats consisted of the subcategories of challenges in the nurse-doctor relationship, some physicians neglecting nurses while visiting patients, and tensions in the relationship between nurses and supervisors. Afriyie (18) and Mahdizadeh et al. (20), who investigated nurses' perceptions regarding intra-professional communications reported that the most critical problem in this area was nurses being subjected to non-respectful behaviors by physicians. Physicians’ lack of knowledge of the nursing profession (21) and holding clinical rounds without the presence of nurses (15) have been reported as the factors compromising the nurse-physician relationship, which were also noted among the experiences of our participants. In this study, although nurses acknowledged threats to inter-professional communication, factors such as the nurse's easy access to the physician and the intimate relationship with ward physicians found empathetic communication between nurses and friendly behaviors between them to be effective in communicating with physicians. This result is one of the unique results of this research.

The third theme in this study included communication with opposite-gender patients as a missing factor in nursing care. One category under this theme was oncology male nurses’ communication challenges, consisting of the subcategories of female patients avoiding male nurses, male nurses’ lack of empathy in their communications, cultural restrictions in male nurses’ relationships with patients, and more attraction of pediatric cancer patients to female nurses. In line with the present study, Buljac-Samardzic et al. believe that men tend to establish clear, quick, and realistic relationships while women prefer to be more deeply involved in discussions and comprehend events in more detail (22). Also, Nakhaee and Nasiri reported a more positive relationship for female nurses than their male counterparts (23) and related this difference to their different attitudes and beliefs.

In line with the present findings, Norouzinia et al. noticed a significant association between gender and the mean score of communication skills, reporting a higher mean score for female nurses compared to male nurses (10). One of the reasons for this finding is the structural differences between men and women in communication.

As illustrated by the nurses, male nurses have more difficulties in communicating with pediatric patients. Likewise, Wittenberg et al. (7), Norouzinia et al. (10), and Banerjee et al. (5) reported that the age difference between the nurse and the patient was another communication barrier. In fact, it seems the generation gap to be a barrier to nurse-patient communications.

In the present study and based on the participants’ experiences, it was revealed that patients had more trust in the same-gender nurses, and female patients were more willing to have female nurses performing invasive procedures and insisted on receiving care from female nurses. Generally, patients were more comfortable verbally communicate with the same-gender nurses. Oxelmark et al. also described that when caregivers and patients were of the same gender, caregivers were more interested to be engaged in discussions about patients’ personal issues (24).

Likewise, in the studies of Wittenberg et al. (7) and Norouzinia et al. (10), patients asserted that the opposite gender of the patient and the nurse was an obstacle to effective communication between them and admitted that this issue was a function of cultural and religious beliefs. This issue is mostly influenced by the cultural and religious conditions of the place.

The last theme in this study was the marginalization of communications in the era of the coronavirus pandemic. This theme consisted of the categories of the weakening of communications with patients and the disheartening of nurse-patient communications during the pandemic. Health care workers are at the frontline of the fight against COVID-19; thus, they are more likely to be exposed to the infection. Studies have shown that the rate of exposure to the infection among health care workers has been 3.8% during the pandemic, the main reason of which has been unprotected contact with infected patients at the beginning of the outbreak (25). Also, nurses have been under double psychological pressure due to the disease. In line with our findings regarding the oncology nurses’ experiences in communicating with patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, Fawaz et al. reported that during the COVID-19 outbreak, nurses were always concerned about their communications with patients and perceived this issue as an essential parameter of their profession to ensure that patients receive appropriate treatments. Nevertheless, nurses have always had concerns regarding their own and their patients’ safety against the coronavirus, believing that social distancing is an essential requirement for providing oncology care during the pandemic (26).

Communicating with cancer patients and providing them with supportive care have been among essential challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Before the pandemic, cancer patients could receive compassionate care and support from the medical team, but this process has been compromised because of the pandemic. Actually, COVID-19 has led people towards unwanted seclusion. In fact, the health protocols that have to be observed and the fear of getting infected with coronavirus have changed the way people empathize with and care for each other, leaving a gap in our communications and depriving us of effective relationships.

One of the strengths of this study was that it divulged oncology nurses’ experiences in their communications during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran, which can help boost our knowledge of the effects of the pandemic on relationships. There was a limitation in our study, as it was performed among oncology nurses from one region of Iran (i.e., east and southeast); therefore, it may not reflect all communication challenges in caring for cancer patients in Iran.

5.1. Conclusions

According to our results, it can be mentioned that communication plays a key role in providing effective nursing care for cancer patients, and communicative challenges of nurses can be reduced by various strategies, including empowering nurses with cognitive empathy. In fact, cognitive empathy is the ability to understand the feelings of others without having a role in their formation and can be educated to oncology nurses as a vital communication skill. Additionally, recommendations and suggestions for future research focusing on communication models such as the Comfort model and its proposed strategies (7) can help improve nurses’ communication skills.