1. Background

Suicide, defined as an intentional attempt to hurt oneself, is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon which is influenced by individual, familial, social, and cultural factors (1, 2). Suicide consists of a continuum of suicide ideation, planning, and suicide attempts (3). Suicidal ideation and self-harm are considered by the World Health Organization (WHO) as highly important concerns regarding psychological and social health (4, 5). Therefore, identifying the psychological factors associated with suicidal ideation is a priority to prevent individuals from committing suicide (6).

Even though the exact rate of suicide prevalence is not easily attainable, studies have shown that suicide in adolescents is on the rise (7, 8). In 2017, for example, 47000 individuals lost their lives due to suicide, and suicide was ranked as the tenth cause of death (7).

In Iran, the prevalence of suicidal ideation, planning, and attempts have been estimated 12.7%, 6.2%, and 3.3%, respectively. As for the prevalence of given suicidal factors for previous year, they were 5.7, 2.9, and 1%, respectively (9). According to some studies, Iranian adolescents between 15 to 24 - 25 and between 25 to 34 years of age make up a big part of suicide attempt cases (10). In addition, the growing rate of suicide attempts and deaths resulting from it in the past 10 years are indicative of the heightened risk of suicide in Iran (10, 11).

Suicidal behaviors have been identified as important issues by the researchers from all over the world (12, 13), and the prevalence of these behaviors had been increasing (14). Since few people report their suicidal ideation, however, the probability that these statistics underestimate the real rates of suicide is high (15).

Previous studies have shown that adverse childhood experiences are common predictors of future suicidal ideation and behaviors (16, 17). In fact, the unavailibility of parents and a failure to develop a secure attachment have been found to relate to a history of suicidal thoughts or attempts (18). In addition, studies on attachment and individuation have also revealed that students with a history of suicide have the lowest degree of secure attachment and individuation in their ongoing relationship with parents (19).

Parental bonding has recently attracted considerable research attention in the field of attachment (20). Studies have shown that parental affectionless control is related to suicidal behavior (21). In addition, studies have shown that parental bonding (22, 23) has a direct effect on suicide and is also indirectly associated with a number of factors mediating suicidal ideation, namely shame (24) and guilt (25). Shame and guilt are parts of a category of emotions called “self-conscious emotions” (26-28). Shame and guilt have been reported to play central roles for many individuals who committ suicide (29-31). Many commentators believe that shame is formed out of personality development and the individuation of the child from his/her mother or primary caregiver (32).

The above discussion is supported by several studies showing that vulnerabilities to shame and guilt feelings are two emotions that are greatly influenced by attachment style and childhood relationships (33). On the other hand, evidence has suggested that excessive parental control (overprotectiveness) is associated with shame in men and guilt in women (34). The results of a study have indicated that there is a relationship between overprotective parental bonding and manifestations pertaining to difficulties in separation-individuation (35).

Although nemerous studies have investigated suicide, predicting suicide attempt and the death caused by it, both in a scientifically controlled environment and in reality, have been remained a major challenge (36). To date, studies have found the role of different factors in suicidal ideation formation, such as high levels of self-criticism (37), excessive perfectionism (38), anxiety (39), eating disorders (40), parental bonding (41, 42), low self-esteem (43) depression and hopelessness (44), feelings of shame and guilt (29), and separation-individuation problems (45).

However, since it seems that parental bonding can play a more fundamental role than other factors related to mental health (46-50), in addition to the central role of shame and guilt in suicide (30, 51) and the association with other risk factors related to suicide including low self-esteem and depression (52, 53), the present study explores the role of these factors in suicide.

2. Objectives

The current study aimed to investigate the relationship between parents and suicidal thoughts through the mediating role of self-conscious emotion (shame and guilt) and separation-individualism.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

The population of this cross-sectional study conducted during the academic year 2018 - 2019 in Tehran’s public universities were all students. A multi-stage cluster sampling was adopted in order to select this sample. To this end, all public universities located in Tehran city were first identified, and universities of Tehran, Shahid Beheshti, Amir Kabir, and Allameh Tabatabai were selected randomly. Then three faculties from each university, as well as three undergraduate classes, two master's classes, and one doctoral class from each faculty were randomly selected. The inclusion criterion was willingness to participate in the study, and the exclusion criteria was the lack of cooperation in completing the questionnaires. Free Calculators Version 4 was used to calculate the sample size, which determined 602 as the needed sample size by taking into account the number of observed variables (263) and latent (16) in the model; it also predicted the effect size (0.19), statistical power (0.8), and confidence interval (95) (0.05 percent error).

3.2. Tools

The research tools were as follows:

3.2.1. Parental Bonding Instrument (The Mother and Father Form)

The Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) consists of two forms with 25 questions developed by Parker and colleagues (1979) to assess two attributes of care and overprotectiveness of mothers and fathers, as perceived by the child. In this questionnaire, participants are asked to recall the first 16 years of their lives and rank the behaviors and attitudes of their parents during this period based on a 4-point scale. The initial assessments of the test is reliability which is, based on Cronbach’s alpha and acoordint to Parker, a value between 0.62 and 0.63 for the care subscale and between 0.66 and 0.87 for the overprotectiveness scale (54). To determine the questionnaire’s reliability in Iran, Cronbach's alpha was used, and the reliability coefficients for care and overprotectiveness attributes were found to be 0.83 and 0.67, respectively. To determine the validity of the questionnaire, moreover, the correlation of each question with the overall score of the related factor was used. The results of the items’ correlations were 0.56 to 0.72 for the care attribute and 0.52 to 0.63 for the overprotectiveness attribute (55). Cronbach's alpha in the current study had a value of 0.70.

3.2.2. Test of Self-conscious Affect (TOSCA-3)

Tangey and Dearing developed the self-conscious affect scale for adults. This scale includes varied events that may take place in everyday life. The third version of the test of self-conscious affect was developed on a 5-point Likert Scale and included 70 items in the form of 16 scenarios (11 positive scenarios and 5 negative scenarios). The scenarios of this version consist of items that assess proneness to guilt (16 questions), proneness to shame (16 questions), detachment (11 questions), externalization (16 questions), alpha pride (5 questions), and beta pride (5 questions) (56). Tangny and Dearing have reported Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.78 to 0.88 for proneness to shame and Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.70 to 0.83 for proneness to guilt (57). Cronbach's alpha reliability scores for guilt and shame in Iran were reported to be 0.64 and 0.78, respectively, and 0.46 and 0.39 for the same values tested a week later. In addition, the findings from this study regarding the validity of the TOSCA-3 were consistent with results from the study by Woien at al. (34). The results of their study showed that the subscales proneness to shame, proneness to guilt, and externalization had high validity, as well as the subscales detachment, alpha pride, and beta pride had low validity or no validity (58). In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha value for this scale was 0.88.

3.3. Psychological Separation Inventory (PSI)

The Psychological Separation Inventory, developed by Hoffman, assesses individuals perception of seperations from parents. This inventory consists of 124 questions (62 questions about the mother and 62 ones about the father) and is rated on a 5-point Likert scale in which all the items are scored directly. Functional independence, emotional independence, conflictual independence, and attitudinal independence are the subscales that make up this inventory. Alpha coefficient for internal consistency has been found to be between 84% and 92%. In addition, Hoffman used confirmatory factor analysis to examine the questionnaire's construct validity by dividing questions about the mother and father. Factor analysis has reported the goodness of fit for the proposed theoretical framework (59). In Iran, Cronbach’s alpha was estimated 84 - 93% for psychological separation subscales (60). Cronbach's alpha for this subscale in the current study was estimated at 0.95.

3.4. Beck Scale of Suicide Ideation (BSSI)

This scale designed by Beck to evaluate suicide ideation consists of 19 questions. The questions in this scale are rated on a 3-point Likert Scale based on an ordinal scale from 0 - 2, and the total score is between 0 and 38. Beck Scale of Suicide Ideation consists of three factors of preparation for suicide (7 questions), desire to death (5 questions), and actual suicide desire (4 questions). This scale has high validity and reliability. Reliability of this scale obtained by Cronbach’s alpha was 0.9, whereas it was 0.74 when using test-retest reliability. Validity of BSSI were found to be 0.95 and 0.88 by using the alpha method and split-half method, respectively. In addition, the results of the study by Anisi at al. have shown that there is a significant relationship between this scale and Goldberg’s Global Health scale. Therefore, this scale has concurrent validity (61). Cronbach’s alpha value for the current study was 0.89.

After providing the participants with necessary explanations as well as taking into account the study’s inclusion criterion and the attrition, 630 questionnaires were distributed among participants by sharing the link of online questionnaire with them. Written consent was obtained from all participants before handing out the questionnaires. In addition, confidentiality and anonymity of the participants were ensured. During the study period, individuals unwilling to complete the questionnaires were excluded from the study. After the collection and evaluation of questionnaires, 49 questionnaires were excluded from the study due to incomplete submissions, and 581 questionnaires were entered in SPSS version 21.

Finally, Pearson’s correlation and structural equation modeling were used to analyze the relationship between the study’s variables as well as to assess the extent of the fitness of the model respectively. In order to assess the mediating relationship of feelings of guilt, shame, and separation-individuation, moreover, the Bootstrap method was adopted. SPSS version 21 and AMOS version 24 were used for analyzing the data.

4. Results

The study was performed on a sample of 225 male and 348 female students aged 28.90 ± 7.71 years on average. Out of all students, 53.1% (304 ones) were undergraduate students, 39.8% (228 ones) were postgraduate students, and 7.1% (41 ones) were doctoral students. As for the marital status of the participants, 60 percent (344 ones) of the population were single, 37 percent (212 ones) were married, and 3 percent (17 ones) were divorced. The mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis of the research variables as well as their descriptive characteristics are presented in Table 1. The correlation between the research variables are also shown in Table 2.

| Variables | M | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide | 3.84 ± 4.33 | 1.285 | 1.309 |

| Parental bonding with mother | 39.71 ± 6.14 | 0.056 | -0.132 |

| Parental bonding with father | 38.95 ± 7.18 | 0.41 | -0.388 |

| Separation from mother | 100.24 ± 24.36 | 0.239 | 0.055 |

| Separation from father | 94.88 ± 25.80 | 0.075 | 0.119 |

| Shame and guilt | 99.07 ± 19.47 | 0.174 | -0.098 |

As Table 1 shows, the mean and standard deviation of the suicide variable were 3.84 and 4.33, respectively. The research variables' correlation matrix is shown below. Skewness and Kurtosis Statistics were used to examine the normal distribution of the six variables. The results of examining normality and collinearity are shown below.

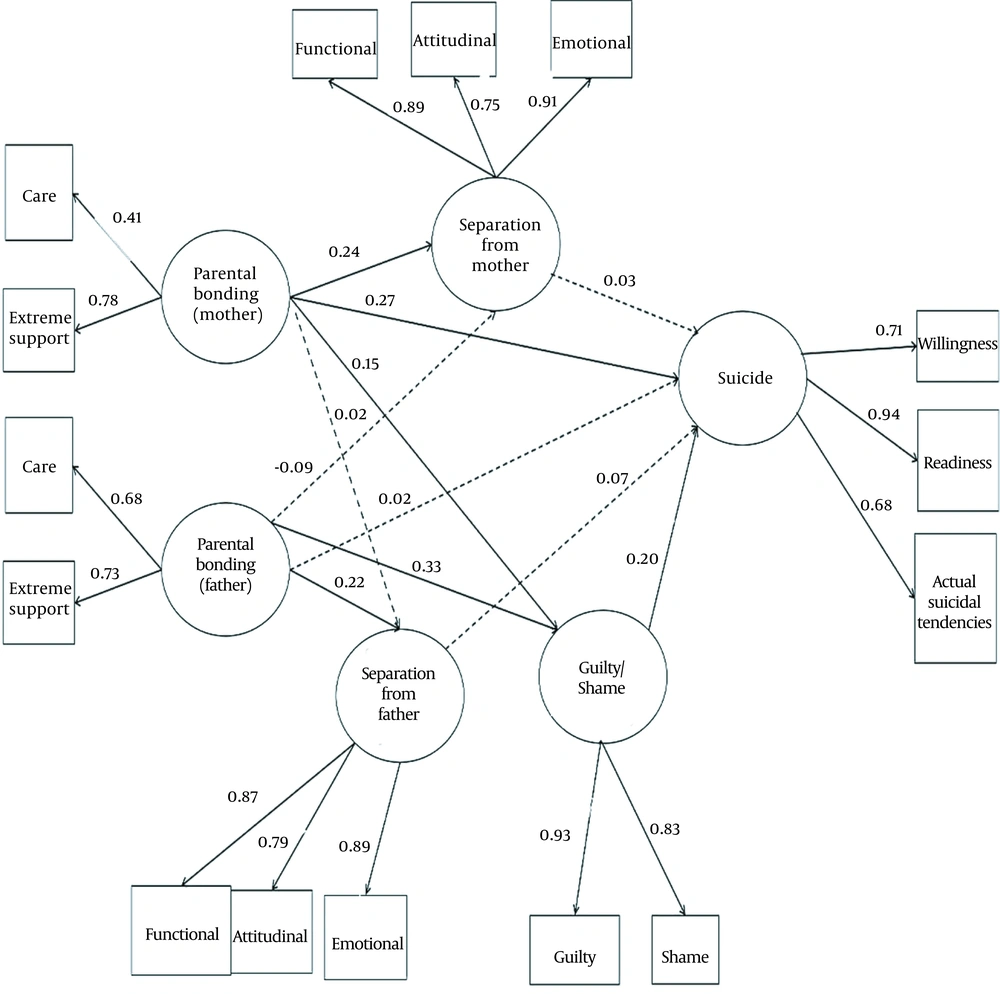

Suicide, parental bonding with mother, parental bonding with Father, separation from mother, separation from father, as well as and shame and guilt were assessed. According to Chou and Bentler, the cut-off points of 3 are suitable for skewness (62). Kurtosis index values above 10 in structural equations modeling are generally problematic (63). The results for the variables' skewness and Kurtosis values show that the distributions are normal. The assumption of collinearity can also be guaranteed because no tolerance index value was less than 0.01, and no variance inflation factor value was greater than 10 when the variance inflation factor (VIF) and Tolerance Indexes were used to test the assumption (64). In the current study, univariate outlier data were identified using a box diagram, and multivariate outlier data were identified by computing mahalanobis distances for each participant. As a result, eight participants were eliminated from the analysis. The results of investigating the direct and mediation effects are shown in Figure 1, after structural equation modeling was used to do so.

The following is the table showing the correlation matrix.

As can be seen in Table 2, there was a significant relationship among all variables investigated in this study, except for the variables of separation from mother and separation from father, which had no significant relationship.

a P < 0.01.

b P < 0.05.

Figure 1 depicts significant paths as continuous lines and non-significant paths as non-continuous lines by using structural equation analysis.

Table 3 displays the structural model fit indices for the entire sample. As shown in the structural structural model fit indices showed a good fit to the model, confirming the research's hypothetical model structure.

| Fit Indices | Acceptable Domain | Statistics |

|---|---|---|

| χ2 | 463/715 | |

| χ2/df | Less than 5 | 5/210 |

| CFI | Greater than 0/90 | 0/920 |

| IFI | Greater than 0/90 | 0/920 |

| GFI | Greater than 0/90 | 0/911 |

| RMSEA | Less than 0/10 | 0/086 |

| SRMR | Less than 0/08 | 0/094 |

According to Table 3, two variables showed significant relationship with each other when T-statistic was out of range (+1.96 and -1.96) or significance level was less than 0.05.

Findings in Table 4 shows the direct and modifying influences of research variables on suicide.

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | Non-standardized Coefficients | Standard Coefficients | T | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental bonding with mother | Suicide | 0.117 | 0.269 | 4.068 | 0.001 |

| Parental bonding with father | Suicide | 0.003 | 0.023 | 0.392 | 0.695 |

| separation from mother | Suicide | 0.002 | 0.027 | 0.449 | 0.653 |

| separation from father | Suicide | 0.004 | 0.072 | 1.224 | 0.221 |

| Shame and guilt | Suicide | 0.013 | 0.203 | 3.963 | 0.001 |

| Parental bonding with mother | Separation from mother | 1.708 | 0.238 | 3.91 | 0.001 |

| Parental bonding with father | Separation from mother | 0.162 | 0.023 | 0.429 | 0.668 |

| Parental bonding with mother | Separation from father | -0.21 | -0.087 | -1.657 | 0.098 |

| Parental bonding with father | Separation from father | 0.521 | 0.224 | 3.989 | 0.001 |

| Parental bonding with mother | Shame and guilt | 1.038 | 0.151 | 2.713 | 0.007 |

| Parental bonding with father | Shame and guilt | 0.755 | 0.329 | 5.504 | 0.001 |

According to Table 4, there was a significant direct relationship between the suicide variable and parental bonding with the mother (β = 0.269, T = 4.068). Significant direct relationships were found between the suicide variable and the shame/guilt variables (β = 0.203, T = 3.963). It was discovered that the parental bonding variable's direct paths with mother to separation from mother variable was significant (β = 0.238, T = 3.910), the direct paths of the variable of parental bonding with father to separation from father variable was significant (β = 0.224, T = 3.989), and the direct paths of the variable of parental bonding with mother to shame and guilt variables were significant (β = 0.151, T = 2.713). It was also detected that the direct paths of the variable of parental bonding with father to shame and guilt variables were significant (β = 0.329, T = 5.504).

To ascertain the indirect effect, the Bootstrap method with a 2000 times sampling process was used. According to Bootstrap mediation analysis, the indirect effect of the latent variable of parental bonding with mother through shame and guilt had a significant impact on the suicide variable (b = 0.013, P < 0.05). Additionally, it was found that the relationship between the latent variable of parental bonding with the father and the suicide variable had a significant indirect effect (b = 0.010, P < 0.05).

5. Discussion

This study mainly aimed to answer the question of whether or not communication with parents and emotions like shame and guilt were associated with suicidal ideation. To the best of our knowledge, our study was the first study that examined the mediating role of shame, guilt, and separation-individuation in the relationship between parental bonding and suicidal ideation. The results showed that the direct path of the maternal bonding variable to the suicidal ideation variable was significant. In previous researches, the relationship between suicidal tendency and maternal bonding had been found to be stronger than this relationship with paternal bonding (65). This finding was consistent with the results of previous studies in terms of the given relationship (21, 66, 67).

This finding may have been explained by the fact that in the first years of a child’s life, it’s basically the mother who takes care of him and exerts greater influence on his personality. Parents who are over protective and over-interfering, or rejecting and punitive, can make the child vulnerable to suicide (67). When adolescents are not able to satisfy their needs related to secure attachment style, they become distrustful of others’ availability and, therefore, their self-worth decreases and they become vulnerable to depression, helplessness, and hopelessness which, in turn, increase the risk of suicidal behaviors (50). The difference between the mother and father’s influence may be associated with the historical role of mothers, compared to fathers, in child-rearing and home environment (65). This discrepancy may have also been attributed to cultural factors. In countries where mothers have the main role in child-rearing, maternal affectionless control perceived by the child may be more significant than paternal bonding (68). Overall, presumably because mothers enter the child’s mental world earlier and more than the father, they tend to have a more direct effect on the child’s mentality.

In addition, the indirect path of the paternal bonding variable to the suicide variable was significant, and this result was indicative of the mediating role of shame and guilt in the relationship between parental bonding and suicidal ideation. This finding was also consistent with the results of previous studies (69, 70). This finding may have also been explained by the fact that the main attributes of parental bonding (control and care) are related to parenting styles. Accordingly, parents who exercise severe control and place restrictions over their children and establish low levels of verbal interaction with them cause the child to feel inadequate which, in turn, can give rise to feelings of shame and guilt (71). Parental overprotection can cause the child to become dependent on others and make him/her more sensitive of what others think of him/her, which can eventually lead to the reinforcement of shame in the child (34). In addition, children raised by over-protective parents tend to view the outside environment as overly threatening and uncontrollable, which in turn raises their anxiety levels. These children tend to depend more on their parents to do essential everyday activities. Therefore, they suffer from a diminished sense of competence to deal with reality, which leads to higher levels of anxiety for them (68). Since anxiety is closely associated with suicidal behaviors (72, 73), over-interference and overprotectiveness of parents can indirectly lead to the rise of self-destructive, suicidal thoughts and attempts in children (74).

Another hypothesis suggests that parents who overly control their children, disregard their needs and abilities, and overly criticize them cause them to internalize the parents as highly aggressive and critical ones as well as develop a superego with extremely high standards. Children with this type of superego usually have unrelenting standards for their own behaviors and want and easily develop feelings of guilt, shame, and self-blame within themselves, which prepare the ground for pathology (75) and suicide (76). Shame is related to failure in achieving one’s ideals, wishes, and goals and can be perceived as a sign of inadequacy and one’s lack of ability to control and understand events (77). Shame triggers feelings of anger, aggression, or humiliated fury (52), which are directed toward the self in suicide (78).

The findings of the current study regarding the non-significance of the separation-individuation variable in the relationship between parental bonding and suicidal ideation were inconsistent with the results from studies by Schimmenti et al. (79) and de Jong (19). According to Wade, the origin of suicide in adolescents lies in the separation-individuation stage, and girls use suicide as a means of regression (type of defense mechanism) to the stage of symbiotic living with the mother (first experience of security) (45). Incomplete psychological separation leads to confusion of the self, and object representations increase suicide vulnerability in the individual (80). For individuals who are psychologically fused with their mothers, suicidal ideation can be experienced as escaping the feeling of maternal engulfment (81). However, the non-significance of this relationship may be due to the nature of the questionnaire’s questions. The items on the PBI mostly assess the emotional bond with the parent. However, the Psychological Separation Inventory items evaluate the conflictual separation, emotional separation, and attitudinal separation. It could be concluded that parental emotional bonding, compared to attitudes, can predict suicidal ideation more accurately.

The study had a number of limitations. First, it was a cross-sectional study and, therefore, unable to analyze behavior over a period of time and determine cause-effect relationships. Second, the study samples were selected only from among students of public universities of Tehran, which restricted the generalizability of the results to individuals with different educational, age, and psychological backgrounds. Therefore, it was suggested that further studies should be conducted on other populations – including clinical samples and suicide attempt cases, in particular – in order to increase the generalizability of the future study findings. In addition, it was recommended that extra research attention should be paid to gender differences and the different mechanisms of shame and guilt in females and males. Clinicians were also encouraged to pay attention to the role of feelings of shame and guilt, especially guilt, as an important treatment outcome when presenting interventions.

5.1. Conclusions

It was concluded that mothers played an unmediated role in the emergence of suicidal ideation. It was also found that low parental bonding increased vulnerability to depression, and that overly controlling, overprotective, and highly critical or demanding parents may have given their children the feelings of inadequacy, shame, and guilt. Shame and guilt were discovered to be effective key factors in the emergence of suicidal ideation. Therefore, perception of parental bonding quality, especially maternal bonding, and the intensity of feelings of shame and guilt may have played important roles in identifying factors related to suicidal ideation. Attention to this issue may positively contribute to developing approprite treatment and prevention strategies.