1. Background

Neglecting sexual issues and dissatisfaction can have adverse effects on individuals, including depression, anxiety, decreased self-confidence, and isolation, and can lead to problems in family and marital relationships, which might ultimately result in emotional or legal divorce (1). Therefore, sexual behavior affects the sexual satisfaction of couples and addresses their sexual needs, and sexual performance plays a significant role in the stability of marital relationships (2).

One of the factors influencing individuals' sexual behavior and functioning is their perceptions and feelings about sexual relationships and self-awareness of their sexual aspects (3). Sexual self-concept is a part of individuality or sexual identity and involves a person's understanding of their sexual orientations and desires (4). It refers to an individual's perspective on themselves as sexual beings and encompasses their thoughts and feelings about sexual matters (5). Sexual self-concept is significantly associated with women's sexual performance, and positive and negative aspects of sexual self-concept can be considered predictive variables of women's sexual performance (6).

Females' sexual lives begin long before their first sexual intercourse, and their pre-intercourse sexual experiences play a crucial role in their sexual understanding (7). The initiation of sexual and romantic experiences in relationships, as well as the prominent growth of sexuality during adolescence, turns this period into a key phase for developing a positive sexual self-concept (8). Sexual self-concept changes over time, grows throughout life, and is influenced by and influences experiences (9). Biological, psychological, and social factors can all influence sexual self-perception (10). Various studies have shown that factors such as age (9), gender (11), race (12), marital status (13), sexually transmitted infections (14), and social factors (15) can impact different aspects of sexual self-perception. Potki (2017) (16) categorized the factors affecting sexual self-concept into biological, psychological, and social factors in their systematic study. A history of sexual abuse during childhood might affect the development of a positive sexual self-concept and put individuals at high risk of sexual disorders. Sexual interaction with coercion and abuse can cause negative emotions, such as guilt, shame, anger, sadness, and despair (17).

Women with positive sexual self-concept have higher levels of sexual response and experience increased sexual satisfaction, marital satisfaction, marital compatibility, sexual self-esteem, sexual self-image, sexual self-efficacy, sexual consciousness, sexual self-blame, and better sexual problem management. Nevertheless, women with negative sexual self-perception experience undesirable sexual performance, sexual problems, sexual anxiety, sexual fear, and sexual depression, making them less likely to cope with sexual problems and engage in sexual activities (18).

Sexual self-concept and its determinants can be essential in planning for the physical, emotional, and psychological well-being of individuals. Previous studies have been conducted in the field of sexual self-concept in married women, and no study was identified that examines sexual self-concept in women before marriage who have not yet initiated sexual activity. Therefore, this study aimed to determine sexual self-concept and its predictors in women on the verge of marriage. Probably, by using the results of this study, women's health policymakers can design programs to strengthen positive sexual self-concept, improve physical and mental health, and ultimately strengthen the foundation of the family.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to determine socio-demographic predictors of sexual self-concept and its dimensions in women on the verge of marriage.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This study was a cross-sectional study conducted within April to September 2022 on 130 women attending pre-marital counseling centers in Tabriz, Iran.

3.2. Participants

The participants in this study were 130 women referring to pre-marriage counseling centers in Tabriz who met the conditions to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria for the study included being on the verge of marriage, being 15 years old or older, and not having any mental or psychological illnesses based on self-report. The exclusion criteria included a history of previous marriage and physical disability.

3.3. Scales

The scales used in this study were as follows:

3.3.1. Personal and Social Questionnaire

This questionnaire is a researcher-made questionnaire and includes questions regarding age, education level, employment status, place of residence, spouse's age, spouse's education level, parents' education level, spouse's occupation, income sufficiency, family support, history of sexual abuse, sexual education, educational resources, and familiarity's way and duration of acquaintance with the future spouse. The validity of the personal and social questionnaire was assessed using content and face validity.

3.3.2. Multidimensional Sexual Self-concept Questionnaire (MSSCQ)

This questionnaire, developed by Snell in 1995, assesses 20 aspects related to sexual self-concept. It consists of 18 dimensions with 78 items rated on a Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (completely). The dimensions are categorized as negative sexual self-concept, positive sexual self-concept, and situational sexual self-concept. The maximum scores for positive sexual self-concept, negative sexual self-concept, and situational sexual self-concept are 176, 64, and 72, respectively; however, the minimum score for these dimensions is 0. The Persian version of this questionnaire, validated by Ziaei et al. in Isfahan, Iran, in 2013 with a sample size of 352 couples, had a Cronbach's alpha of 0.88 (19). A pilot study was conducted on 20 women with an interval of 2 weeks to measure the test-retest reliability of MSSCQ. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and Cronbach’s alpha were calculated at 0.91 and 0.87, respectively.

3.4. Sample Size

The sample size in this study was calculated by G-power software based on the results of Mohammadi Nik et al.’s study (20) regarding the positive self-concept variable and considering the standard deviation of 22.7, d = 0.05 (study accuracy) around the mean (120.73), α = 0.05, and power = 90%. With the consideration of potential dropouts, 130 participants were included in this study.

3.5. Data Collection

In this study, sampling was performed through the convenience sampling method over a period of 6 months after obtaining ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. The researcher visited pre-marital counseling centers in Tabriz and provided a full explanation of the study objectives and methods to women who intended to get married. Women who were willing to participate in the study were assessed for the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and those who met the criteria were selected. After obtaining informed consent, the data were collected using study instruments. The participants received and completed the questionnaires during their visits to pre-marital counseling centers while waiting for test results or before starting educational classes. The personal and social questionnaire and MSSCQ were completed by the researcher through the interview method.

3.6. Data Analysis

After data collection from all study participants, the data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 24; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The normality of quantitative data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies (percentages) and means (standard deviations), were used to describe the participants' demographic and social characteristics and dimensions of sexual self-perception. In order to determine the relationship between different dimensions of sexual self-concept with individual and social characteristics in bivariate analysis, Pearson's correlation tests and one-way analysis of variance were used. Then, to determine the effect of independent variables (personal and social characteristics) on the dependent variable (sexual self-concept) and to control confounding variables, the variables that had a P-value less than 0.2 in the bivariate analysis were entered into the multivariate linear regression test with a backward strategy. Before multivariate analysis, regression assumptions, such as residual normality, residual variance homogeneity, linear outliers, and residual dependence, were studied.

3.7. Ethical Consideration

This study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and relevant guidelines. All participants were given the necessary information about the study, and their informed written consent was obtained. The Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences confirmed the study (ethics code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.386).

4. Results

The mean (standard deviation) age of the women was 24.6 (6.0) years, and the mean (standard deviation) age of their spouses was 28.5 (8.5) years. The majority of women were homemakers, and their spouses were self-employed. In terms of education, most women and their spouses had university degrees; nevertheless, the parents of the participants had secondary education. None of the participants reported a history of childhood sexual abuse. Table 1 shows the demographic and social characteristics of the participants.

| Variables | No. (%) | Correlation with Positive Sexual Self-concept | Correlation with Negative Sexual Self-concept | Correlation with Situational Sexual Self-concept | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | P-Value | Mean (SD) | P-Value | Mean (SD) | P-Value | ||

| Age (y) | 24.7 (6.0) | 0.004 a | < 0.001 a | 0.022 a | |||

| Husband’s age (y) | 28.6 (5.8) | 0. 002 a | 0.004 a | 0.161 a | |||

| Education | 0.039 b | 0.002 b | 0.038 b | ||||

| Guidance school | 33 (25.4) | 112.0 (24.3) | 20.8 (9.2) | 41.8 (11.2) | |||

| High school | 43 (33.1) | 97.6 (17.5) | 12.7 (6.9) | 32.6 (7.9) | |||

| University | 54 (41.5) | 117.4 (16.3) | 13.3 (1.1) | 45.1 (8.2) | |||

| Job | 0.401 b | 0.136 b | 0.128 b | ||||

| Housewife | 73 (56.2) | 118.2 (19.4) | 16.6 (8.0) | 44.2 (10.5) | |||

| Employed | 40 (30.8) | 117.7 (20.8) | 15.5 (7.5) | 44.8 (8.1) | |||

| Student | 17 (13.1) | 114.5 (16.7) | 17.3 (7.0) | 46.2 (8.9) | |||

| Husband’s education | 0.382 b | 0.035 b | 0.789 b | ||||

| Guidance school | 20 (15.4) | 111.3 (21.9) | 19.9 (9.8) | 42.7 (11.5) | |||

| High school | 53 (40.8) | 114.2 (21.1) | 18.2 (9.1) | 43.5 (11.4) | |||

| University | 57 (43.8) | 121.1 (15.2) | 13.8 (5.2) | 46.4 (9.6) | |||

| Husband’s job | 0.164 b | 0.128 b | 0.411 b | ||||

| Unemployed | 9 (6.9) | 111.0 (21.1) | 15.1 (7.0) | 44.0 (8.5) | |||

| Worker | 26 (20.0) | 114.5 (16.9) | 18.2 (9.3) | 44.8 (9.8) | |||

| Employed | 31 (23.8) | 120.7 (16.0) | 13.6 (5.4) | 46.5 (9.1) | |||

| Self‑employed | 64 (49.3) | 118.4 (22.3) | 16.7 (8.0) | 43.8 (9.9) | |||

| Father's education | 0.126 b | < 0.001 b | |||||

| Guidance school | 50 (38.4) | 106.4 (19.7) | 18.2 (9.2) | 42.0 (9.2) | |||

| High school | 37 (28.5) | 119.4 (19.1) | 15.0 (5.0) | 47.0 (9.5) | 0.183 b | ||

| University | 43 (33.1) | 121.6 (19.1) | 13.5 (6.5) | 45.3 (9.4) | |||

| Mother's education | 0.083 b | 0.002 b | 0.301 b | ||||

| Illiterate | 5 (3.8) | 125.0 (23.4) | 24.7 (11.0) | 43.5 (13.5) | |||

| Guidance school | 63 (48.5) | 113.2 (20.6) | 18.2 (8.2) | 43.1 (9.8) | |||

| High school | 41 (31.5) | 120.2 (19.4) | 14.1 (6.1) | 46.8 (9.0) | |||

| University | 21 (16.2) | 124.4 (17.5) | 13.3 (6.5) | 45.4 (9.6) | |||

| Economic situation | 0.019 b | 0.431 b | 0.130 b | ||||

| Favorable | 25 (19.2) | 123.7 (22.7) | 14.9 (7.4) | 43.3 (8.9) | |||

| Relatively favorable | 74 (56.9) | 117.9 (17.7) | 16.4 (7.9) | 45.7 (9.6) | |||

| Unfavorable | 31 (23.8) | 105.0 (25.6) | 18.2 (8.3) | 40.5 (10.8) | |||

| Family support | 0.113 b | 0.026 b | 0.850 b | ||||

| Much | 25 (19.2) | 124.0 (19.4) | 15.0 (8.2) | 45.1 (9.6) | |||

| Medium | 74 (56.9) | 117.5 (19.9) | 15.4 (7.2) | 44.9 (9.0) | |||

| Low | 31 (23.8) | 112.7 (20.3) | 19.6 (8.3) | 43.8 (11.4) | |||

| Source of information on sexual issues | 0.902 b | 0.278 b | 0.637 b | ||||

| No previous sex education | 78 (60.0) | 116.5 (21.0) | 17.0 (8.2) | 43.7 (10.0) | |||

| Parents | 24 (18.5) | 121.3 (23.8) | 17.5 (8.1) | 46.4 (9.3) | |||

| Friends | 8 (6.2) | 116.7 (16.7) | 14.1 (5.2) | 47.1 (7.2) | |||

| Cyberspace | 5 (3.8) | 119.2 (11.9) | 11.4 (3.6) | 42.6 (11.8) | |||

| Training class | 15 (11.5) | 117.4 (12.7) | 14.0 (6.4) | 46.2 (9.6) | |||

| The method of introduction | |||||||

| Traditional marriage | 58 (44.6) | 113.5 (22.1) | 18.7 (8.8) | 43.1 (10.2) | |||

| Family marriage | 14 (10.8) | 117.7 (14.6) | 0.153 b | 17.3 (7.0) | 0.004 b | 44.0 (11.1) | 0.356 b |

| Previous acquaintance | 58 (44.6) | 124.4 (18.8) | 15.7 (3.8) | 46.7 (9.5) | |||

| Duration of acquaintance | 0.004 b | < 0.001 b | 0.073 b | ||||

| No acquaintance | 38 (29.2) | 111.3 (22.8) | 1.0 (8.9) | 43.3 (10.8) | |||

| < 1 year | 66 (50.7) | 121.8 (16.5) | 14.6 (6.9) | 45.1 (8.9) | |||

| 1 - 2 year | 10 (7.7) | 121.6 (22.8) | 12.5 (4.0) | 49.0 (7.1) | |||

| > 2 years | 16 (12.4) | 119.9 (16.5) | 13.2 (5.1) | 46.5 (8.5) | |||

a Pearson correlation test.

b One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

The results of the bivariate analysis showed a significant statistical association between age, spouse's age, education level, economic status, and duration of acquaintance with positive sexual self-concept (P < 0.05). Similarly, there was a significant association between age, spouse's age, education level, spouse's education level, parents' education level, family support, and duration of acquaintance with negative sexual self-concept (P < 0.05). Age and women's education level were also significantly associated with situational sexual self-concept (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

The mean (standard deviation) score for positive sexual self-perception was 117 (20) out of a possible score range of 0 - 176; nevertheless, the mean (standard deviation) score for negative sexual self-perception was 16 (7) out of a possible score range of 4 - 38. The mean (standard deviation) score for situational sexual self-perception was 44 (9) out of a possible score range of 0 - 72.

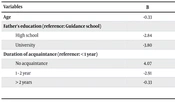

The results of the multiple regression analysis showed that the spouse's age, education level, and mother's education level were predictors of positive sexual self-concept and predicted 12% of the variance of positive sexual self-concept (ADJ. R2 = 0.124) (Table 2). Age, father's education level, and duration of previous acquaintance were predictors of negative sexual self-concept and predicted 21% of the variance of negative sexual self-concept (ADJ. R2 = 0.211) (Table 3), and age was a predictor of situational sexual self-concept and predicted 6% of the variance of situational sexual self-concept (ADJ. R2 = 0.063) (Table 4).

| Variables | Β | SE | Beta | t | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Husband’s age (y) | 0.89 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 2.84 | 0.005 |

| Education (Reference: University) | |||||

| Guidance school | 15.35 | 6.92 | 0.33 | 2.21 | 0.029 |

| High school | 15.72 | 5.30 | 0.36 | 2.96 | 0.004 |

| Mother's education (Reference: Guidance school) | |||||

| Illiterate | 17.21 | 9.90 | 0.14 | 1.73 | 0.085 |

| High school | 13.04 | 5.14 | 0.30 | 2.53 | 0.012 |

| University | 20.20 | 6.88 | 0.37 | 2.93 | 0.004 |

a R = 0.431

b R2 = 0.185

c ADJ.R2 = 0.124

| Variables | Β | SE | Beta | t | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | -0.33 | 0.12 | -0.25 | -2.72 | 0.007 |

| Father's education (reference: Guidance school) | |||||

| High school | -2.84 | 1.65 | -0.16 | -1.71 | 0.089 |

| University | -3.80 | 1.66 | -0.22 | -2.28 | 0.024 |

| Duration of acquaintance (reference: < 1 year) | |||||

| No acquaintance | 4.07 | 1.62 | 0.23 | 2.50 | 0.014 |

| 1 - 2 year | -2.91 | 2.41 | -0.99 | -1.20 | 0.229 |

| > 2 years | -0.33 | 2.00 | -0.01 | -0.16 | 0.866 |

a R = 0.509

b R2 = 0.260

c ADJ.R2 = 0.211

5. Discussion

The present study was conducted with the aim of determining socio-demographic predictors of sexual self-concept in women on the verge of marriage. Based on the results of this study, all three dimensions of sexual self-concept were within the average range. Moreover, the age, education level, parents' education level, and duration of acquaintance with the future spouse were predictors of sexual self-concept in women on the verge of marriage.

According to the results of this study, the mean (standard deviation) scores for positive sexual self-perception, negative sexual self-perception, and situational sexual self-perception in women on the verge of marriage were within the average range for all three dimensions. The aforementioned results are consistent with the results of studies by Doremami et al. (21) and Mohammadi Nik et al. (20) in all three dimensions of sexual self-perception. The results of a study by Potki et al. (16) on 707 married women in Sari, Iran, are also consistent with the results of the present study regarding positive and situational sexual self-concept, although the mean score for negative sexual self-concept was lower in their study, which can be attributed to the fact that their participants were married and had sexual experiences. Additionally, Jaafarpour et al. (22) observed a moderate positive sexual self-concept and a high negative sexual self-perception in married women in their study, which could be related to the lower education level of their sample than the current study.

The results of the present study in the field of individual and social predictors of sexual self-concept indicated that the predictors of positive sexual self-concept were education, spouse's age, and mother's education. Additionally, the predictors of negative sexual self-concept were age, father's education, and duration of acquaintance. Moreover, age was the only individual social predictor of situational sexual self-concept. Hamidi et al. (18), in their study with the aim of reviewing biological-psychological-social factors related to women's sexual self-concept, reviewed 41 articles in this field and stated the factors related to sexual self-concept in three general categories: Biological factors, including age, gender, race, marital status, disability, and diseases, psychological factors, including body image, childhood sexual abuse, and mental health, and social factors, including parents and peers, relationship with spouse, and media.

The present study identified age as a predictor of sexual self-concept among individual factors. Hensel and Deutsch showed that as age and sexual experiences increase, anxiety and concerns about sexual matters decrease, leading to the development of sexual self-concept and influencing individuals' future behavior (5, 9). The education level of parents was another predictor of sexual self-concept. Parents are generally considered the primary sexual educators for their children and one of the most important sources of information on sexual matters (23). Therefore, the high education level and awareness of parents, particularly mothers, are important in shaping positive sexual self-concept in girls.

Hamidi's literature review study highlighted the role of spousal relationships, stating that women with excellent emotional relationships with their spouses scored higher in positive sexual self-concept and lower in negative sexual self-concept. Furthermore, behaviors associated with love, intimacy, and attachment form the core of the sexual self-concept (18). In the present study, the participants were women on the verge of marriage without a history of sexual abuse, and the duration of acquaintance with the future spouse was a predictor of sexual self-concept, with longer acquaintance periods associated with lower negative sexual self-concept.

Sexual self-concept provides an understanding of an individual's sexual aspects. The way individuals feel about themselves as sexual beings will significantly impact their sexual behaviors and experiences (21). Addressing and strengthening the positive aspects of sexual self-concept can prevent risky sexual behaviors in the future and promote women's mental health and well-being (24). Having a history of sexual abuse in childhood is one of the important factors that determine sexual self-concept; it is also influenced by the social and family environment (25). However, none of the women in the present study reported a history of sexual abuse in childhood, which might be due to cultural and religious issues in Iran. Therefore, by planning interventions to enhance positive sexual self-concept for women and their families through psychological, educational, and counseling approaches, it is possible to improve mental and sexual health, ultimately leading to stronger family foundations.

One of the strengths of this study is that it is the first to assess sexual self-concept in women on the verge of marriage. However, the limitations of this study included the assessment of sexual self-concept questionnaires, which might have led participants to withhold true answers due to cultural and social taboos, and the use of the convenience sampling method. It is suggested that future studies employ further extensive quantitative or qualitative studies with a large sample size and a random sampling method to establish better results in assessing the sexual self-concept of women.

5.1. Conclusions

Based on the results of this study, age, education level, parents' education level, and duration of acquaintance with the future spouse were predictors of sexual self-concept in women on the verge of marriage. Considering that sexual self-concept develops during adolescence, policymakers can promote positive sexual self-concept in women by planning interventions, such as education, in order to increase the information of the individuals and their families and to provide conditions for couples to know better each other before marriage, and psychological counseling with sexual health approaches, leading to strengthening family foundations and successful childbearing in the future.