1. Background

Family caregivers, who are relatives or friends providing unpaid care, play a critical role in supporting patients physically, emotionally, and socially, particularly those with advanced cancer (1). These caregivers are integral throughout the illness and especially at the end of life (2). However, the stress of caring for loved ones during the final stages of life, coupled with the subsequent death, can lead to a significant caregiving burden and long-term emotional distress, even when the caregiving is undertaken voluntarily (3). These caregivers may struggle to meet the expectations of their role, impacting their ability to adjust to the grieving process following the patient's death (4).

With patients with advanced cancer living longer today, the extended period of caregiving can profoundly affect caregivers' responses to the end of their relationship with the patient upon their death (3). Therefore, family caregiving and grieving are interconnected, forming parts of a chronic stressor that includes caregiving, death, and mourning. This stressor can have cumulative effects on the caregiver's well-being (4).

Mourning, the stage following the death of an individual, involves the caregiver adjusting to the new reality of living without the deceased (5). In the case of family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer, the prevalence of psychological complications post-death is notably high. Studies report 66.1% experiencing significant distress, 68.8% at risk of depression, 72.3% at risk of severe anxiety, and 25.9% at risk of complicated grief (6). These statistics highlight the critical need for targeted support and interventions to help caregivers cope with their profound losses and ongoing mental health challenges.

There is a significant gap in knowledge regarding how family caregivers react to the death of a patient and how the caregiving experience impacts their grief (7). Bereavement research often focuses on the grieving experience without examining the influence of pre-death factors (8). The existence of a long, intimate caregiving relationship between a family member and a patient with cancer makes the experience of caring for a dying patient different from that of other diseases (4). Caregivers of patients with advanced cancer endure significant psychological distress during the course of their loved one's illness (9). Research has predominantly concentrated on explaining the experiences of caregivers while the patient is ill, but little attention is given to the psychological aftermath of caregiving following the patient's demise. Bereaved caregivers frequently encounter symptoms of prolonged grief, sleep disruptions, a sense of purposelessness, and physical problems (10-12). Despite the significant impact of caregiving on the psychological well-being of family members, research specifically focused on the experiences of bereaved caregivers is limited (13-15). Therefore, exploring the experience of family caregivers with all its complexities reveals the need to gain a better understanding of their experience after losing a patient with advanced cancer. Such knowledge is crucial to help health professionals identify at-risk caregivers and proactively intervene to support them (16).

Qualitative approaches and methodologies are crucial in examining human experiences because these methods enable a deep and comprehensive understanding of individuals' experiences, attitudes, tendencies, and needs (17). By employing qualitative approaches, researchers can gain in-depth insights into the experiences of family caregivers after the loss of a patient. Qualitative research allows us to view the loss of a patient with advanced cancer from the perspective of family caregivers.

2. Objectives

The purpose of this study was to explore the unique experiences, needs, and challenges faced by family caregivers after the loss of a patient with advanced cancer. By delving into these areas, the study aimed to provide a deeper understanding of the specific challenges and needs of this population. Additionally, the insights gained are intended to inform the development of effective support interventions tailored to assist family caregivers during their bereavement process.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This qualitative study employed conventional content analysis to describe the experiences of family caregivers after losing a patient with advanced cancer (18). Initially, qualitative content analysis focused on the systematic and quantitative description of the manifest content of communication. Over time, however, the approach has evolved to include the interpretation of latent content as well (19).

3.2. Participants and Setting

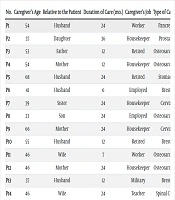

Participants in this study were family caregivers. To ensure a diverse and representative sample, individuals were selected based on purposive sampling, considering various individual characteristics such as age, sex, education, job, and marital status. Fourteen individuals were interviewed, all of whom were willing and able to share their experiences. The inclusion criteria required that participants had no obvious mental or personality disorders and were actively caring for a family member with advanced cancer (Table 1).

| No. | Caregiver’s Age | Relative to the Patient | Duration of Care (mo.) | Caregiver’s Job | Type of Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 54 | Husband | 24 | Worker | Pancreas |

| P2 | 37 | Daughter | 36 | Housekeeper | Prostate |

| P3 | 53 | Father | 12 | Retired | Osteosarcoma |

| P4 | 54 | Mother | 12 | Housekeeper | Osteosarcoma |

| P5 | 68 | Husband | 24 | Retired | Stomach |

| P6 | 41 | Husband | 6 | Employed | Brest |

| P7 | 39 | Sister | 24 | Housekeeper | Cervix |

| P8 | 23 | Son | 24 | Employed | Osteosarcoma |

| P9 | 66 | Mother | 24 | Housekeeper | Cervix |

| P10 | 55 | Husband | 12 | Retired | Brest |

| P11 | 46 | Wife | 7 | Worker | Osteosarcoma |

| P12 | 46 | Mother | 24 | Housekeeper | Osteosarcoma |

| P13 | 37 | Husband | 12 | Military | Brest |

| P14 | 46 | Wife | 24 | Teacher | Spinal Cord |

3.3. Data Collection

Data were collected through face-to-face interviews conducted in a quiet, private setting at Iranmehr Hospital. A total of 14 interviews were carried out, each lasting between 30 and 60 minutes. With the consent of the participants, a voice recorder was used during the interviews to ensure accuracy in data capture. None of the interviewees were excluded from the study for reasons such as unwillingness to participate, providing incorrect information, or lack of proper communication with the researcher.

The primary question posed to participants was, "Please talk about your experience after your cancer patient's death." As the interviews progressed, the type of follow-up questions varied to delve deeper into the responses to the main question. Examples of these follow-up questions included "Can you explain more? What do you mean? Explain a little about this issue." Additionally, participant events and emotional states were recorded as field notes during the interview.

The interview process continued until data saturation was achieved, indicated by the point at which no new information or themes were observed in the data.

3.4. Data Analysis

The researchers employed both manifest and latent content analysis to thoroughly examine the data collected from the interviews. After each interview, the researchers promptly transcribed the discussions verbatim into a Word document. The data was then analyzed using the six steps outlined by Graneheim and Lundman.

3.5. Rigor

To ensure the trustworthiness of the data, the criteria presented by Guba and Lincoln were taken into account. An interview guide based on previous studies and the researcher's experiences was used to increase credibility. Family caregivers with varying levels of experience after losing a patient to advanced cancer were selected. After the initial analysis, the researcher held meetings with the participants to clarify their experiences and reach a common understanding. Peer and member checking were used to assess the conformity of the interviews. Additionally, a person familiar with qualitative research evaluated the text of some interviews to ensure the accuracy of the coding process. To enhance transferability, detailed descriptions of the participants' conditions and background characteristics were provided, allowing for comparison and application in different situations. The study also considered sampling with maximum diversity, which helped enhance transferability. Participants of different ages and cultures were included in the study (18, 19).

3.6. Ethical Considerations

Each participant received both oral and written information about the study, ensuring they were fully informed. Participation was voluntary, and individuals were made aware that they could withdraw from the study at any time without consequence. Confidentiality of all participant information was assured. Additionally, this study was conducted with ethical approval, having obtained the ethical code (IR.BUMS.REC.1401.140) from Birjand University of Medical Sciences.

4. Results

The participants in this study consisted of 9 females and 5 males, with an average age of 39.35 ± 7.52 years. The average duration of care provided by these caregivers was 15.57 ± 7.14 months. From the data collected, three main categories emerged that encapsulate the experiences of family caregivers: Caregiver's Inconsolable Mourning, Unforgettable Experience of Caring for Loved Ones, and Cancer Concerns.

4.1. Caregiver's Inconsolable Mourning

Grief, a constant sorrow for the shared past, and a permanent sense of loss for loved ones are profound for caregivers. They often struggle to come to terms with the death of the patient due to the many shared memories, experiencing more intense grief than other family members. Reflecting on both the good and challenging times with the patient during caregiving becomes a source of torment after the patient's death. Recalling the patient's critical condition, along with the suffering and pain endured during treatment, further intensifies the caregivers' grief. While this feeling may diminish over time, it can be overwhelmingly painful initially. Caregivers often feel as if a fundamental pillar of their life has been removed after the patient's death, accompanied by a deep longing for the patient, which stems from the special bond formed during the caregiving period.

4.2. Unforgettable Experience of Caring for Loved Ones

The category of "Unforgettable Experience of Caring for Loved Ones" includes the subcategories of constant rumination on the caregiving trajectory and the repeated recall of painful memories of loved ones suffering. After the death of the patient, caregivers often reflect on the entire course of the illness, revisiting the decisions made and pondering what else could have been done. This retrospective analysis can exacerbate their grief, particularly when they consider the harsh realities faced by the patient in their final days.

The difficulty caregivers face in accepting the patient's death is often compounded by the traumatic conditions endured by the patient towards the end. Many caregivers are haunted by the belief that their loved one died under the worst possible circumstances, leaving behind memories that are both vivid and painful. This perception makes accepting the death even more challenging, as caregivers struggle with the lingering images of their loved one's suffering and the finality of their loss.

4.3. Constant Mind Involvements

The category of constant mental involvements encompasses subcategories such as regrets in the caregiving process and worries about getting cancer, both of which contribute to persistent sadness and profound contemplation (Table 2).

| Categories | Sub-categories | Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Caregiver's inconsolable mourning | Endless grief | "I don't think I'll ever forget it! Maybe as time passes, I grieve more. Maybe I was a little more patient at first, but as time passes, the pain on my heart feels heavier! His absence bothers me more and more."P10 " The pain hasn't diminished. It's been 10 months now. Only God knows how long it will last."P20 |

| Constant alas for the common past | "You wouldn't believe it, but now every time I want to drink water or tea, I tell myself that my sister couldn't even drink a simple cup of tea."P1 "Yes, I'm in a lot of pain because of these reminders and the repetition of all those memories. It's like my mind can't be free of them for a moment! The smallest thing can remind me of her... I wish I could at least erase the memories of her pain, suffering and crying, so I wouldn't have to suffer so much."P10 | |

| Permanente losing tragedy for loved ones | "The tragedy of losing her was really too heavy for me to bear... Since my wife passed away, the pillar of my life has been completely removed. The foundation of my life is completely ruined. It is a profound sadness."P11 "I really miss her. I miss her so much."P1 | |

| Unforgettable experience of caring for loved ones | Constant rumination of caregiving trajectory | "It's been ten months and we haven't had a good day yet. I mean, remembering those memories has left us with no energy. From the day they passed away until now, there hasn't been a day where I woke up and didn't think about why this happened? Why did it happen that way?"P20 "A long time after they passed away, I decided to go on a trip. I took the kids and went to Mashhad. The whole way there, I was thinking about my wife."P6 |

| Repeated recall of painful memories of loved ones suffering | "To be honest, because I witnessed it all up close, I still struggle with the hardships, as I really saw her pain, moment by moment. It's still hard for me. If my sister had died in a more normal way, I wouldn't be in so much pain."P1 "That's the thing about cancer; you see your loved one wasting away before your eyes, and there's nothing you can do. But if my mom had died in a different way, maybe it would have been a moment of huge shock. On the other hand, the good thing is that I wouldn't have seen her wither away before my eyes."P2 | |

| Constant mind involvements | Regrets in the caregiving process | "I blame myself now. I wish I had realized sooner. I wish I had taken him seriously when he first said his leg hurt. I wish I had done something then!"P22 "At one point during his treatment, they sent us for a liver biopsy. She didn't want to do it. She said that if she went for the biopsy, she might get worse. I told her that the doctor wouldn't know what the mass was made of unless he took a sample. Unfortunately, after the biopsy, the mass grew much faster and he had serious problems. I always tell myself that I wish I hadn't said those things to her. If he had not gone for the biopsy, maybe he would still be alive."P6 |

| Worries about getting cancer | "I always think, 'What would I do if my children get cancer, God forbid?' Because the doctors said that this disease might be hereditary. I always pray, 'God, please don't let my children get this disease anymore. Please let my children be healthy.'"P4 "You have some symptoms and you keep saying, 'I have cancer.' For example, every day when I take a shower, I touch myself and say, 'I have breast cancer. I must have cervical cancer.' I keep thinking about it."P1 |

The first subcategory, regrets, often haunts caregivers with memories and moments from the caregiving journey. These regrets might originate from perceived failures, decisions that could have been better made, or times when caregivers felt they were not providing adequate care. Such reflections can lead caregivers to harbor ongoing remorse about how they managed the caregiving responsibilities.

The second subcategory, worries about getting cancer, involves fears and concerns about the possibility of themselves or other family members developing cancer. This anxiety can stem from the firsthand experience of caring for a patient with cancer, coupled with an understanding of the genetic predispositions to the disease. Such worries often prompt deep reflection on personal and family health, reinforcing the caregivers' ongoing mental engagement with the themes of illness and vulnerability.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to elucidate the experiences of family caregivers following the loss of a patient with advanced cancer. From the data, three main categories emerged that encapsulate the experiences of family caregivers: Caregiver's Inconsolable Mourning, Unforgettable Experience of Caring for Loved Ones, and Constant Mind Involvements.

After navigating numerous challenges while caring for a patient, caregivers begin to mourn the loss once the patient passes away. During this phase, they experience the grieving process differently compared to other family members. According to Hashemi et al., bereaved individuals encounter a wide range of emotions and challenges during mourning, such as feelings of loneliness, sadness, depression, and anger, as well as denial of their loved one’s death, eventually leading to acceptance (20). Furthermore, a study by Alam et al. highlighted that family caregivers are at risk of several adverse outcomes both during the patient's care and afterward, throughout the grieving process. It is suggested that support resources should be routinely provided to them, especially when risk factors for adverse outcomes such as poor social support, pre-loss depression, or lack of preparedness for the patient's death are present (2).

Given the substantial emotional burden and stress associated with witnessing the impending death of a family member, providing psychosocial support during this critical time is crucial to improving their well-being. While family involvement in palliative care at the end-of-life stage is aimed at alleviating psychological symptoms like anticipated grief, the primary focus should also include preventing the development of long-term maladaptive responses, such as complicated grief (21).

Caregivers experience the "Unforgettable Experience of Caring for Loved Ones" following the death of a patient, a phase often marked by significant emotional turmoil. The death of a loved one, or the anticipation of such loss, is recognized as one of the most challenging experiences for families and individuals, frequently leading to severe psychological symptoms such as post-traumatic stress disorder and depression among family members (21). A study by Dumont highlighted that the management of symptoms in patients significantly influences how family members cope with grief. Specifically, the presence of symptoms like confusion, significant behavioral changes, and cachexia can intensify the difficulty of the end-of-life experience for the bereaved family (16).

"Constant Mind Involvements" refers to the ongoing mental and emotional engagement of caregivers after the patient's death. According to Martin et al., caregivers often find themselves overwhelmed with information about treatments, their roles, and what is considered best for them following a terminal illness diagnosis. This can lead to feelings of guilt, fear, and distrust as caregivers reflect on the decisions made throughout the illness (22). Bijnsdorp et al. found that caregivers face several challenges, such as high caregiving intensity, limited time for relaxation, feelings of guilt over placing loved ones in nursing homes, and regrets about not spending enough time with them (23). Carmel et al. noted that 33% of grieving family caregivers of adult cancer patients regretted not having more conversations about death with their loved ones (24). Furthermore, a study by Solberg et al. revealed that family caregivers often feel frustrated and worried about their own health due to inadequate guidance from healthcare personnel and insufficient information, perceiving healthcare services as being primarily patient-focused and not addressing their needs (25).

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of this study reveal that family caregivers undergo distinct experiences following the death of patients with advanced cancer. The development of a strong emotional bond between the patient and the caregiver during the caregiving period often results in caregivers experiencing more intense emotions and feelings compared to other family members after the patient's death. This highlights the undeniable importance of providing support to families who are facing the imminent death of a loved one. Additionally, it underscores the necessity for health systems to identify these individuals during the patient care process and to offer targeted support after the death, recognizing the profound impact that caregiving and loss have on these caregivers.