1. Background

Achieving effective analgesia is a fundamental objective in anesthesia. Over time, anesthesiology has evolved to achieve analgesia through simple, uncomplicated, and cost-effective methods (1). One such method is spinal anesthesia, which involves injecting local anesthetics into the subarachnoid space via the lumbar vertebrae. This results in the reversible blockage of anterior and posterior roots, posterior root ganglia, and parts of the spinal cord, leading to the loss of autonomic, sensory, and motor nervous system functions (2). Local anesthetics of the amide group, including lidocaine, tetracaine, Marcaine, and ropivacaine, are commonly used for spinal anesthesia. These drugs block sensory and motor terminals, providing effective pain control for postpartum and local surgeries. Their mechanism involves blocking sodium channels, raising the stimulation threshold, and slowing nerve depolarization (3). Researchers have explored combinations of Marcaine with other drugs to enhance patient relief (4, 5). Another method used in anesthesia involves the use of opiates within the spinal canal (6). Opiates act on µ-opioid receptors in the gelatinous body of spinal cord. Fentanyl and sufentanil can be administered alongside lidocaine in spinal anesthesia. Fentanyl, a potent narcotic (75 - 125 times stronger than morphine), contributes to analgesia and anesthesia. Injecting varying doses of fentanyl with anesthetics into the subarachnoid space prolongs the duration of analgesia (7). Spinal anesthesia is commonly employed for lower abdominal and lower limb surgeries. Anesthesiologists may opt for spinal anesthesia over general anesthesia for addicted patients based on individual conditions. Individuals with substance addiction often demonstrate reduced pain thresholds and increased resistance to opioids, attributed to altered receptor function or disruptions in endogenous opioid peptide pathways (8). Anesthesiologists indeed encounter the delicate balance of ensuring effective pain control throughout surgery while minimizing adverse effects. Combining narcotics with local anesthetics has become a common strategy to improve spinal block quality and reduce postoperative pain. Previous research has delved into the influence of fentanyl on the duration of sensory and motor blocks, but there remains a need for further investigation (9). Patients addicted to narcotics such as opium may require higher doses of anesthetics because they have a degree of tolerance to anesthetics (10). Also, in these patients, the duration of anesthesia and analgesia is reduced, making it difficult to manage these patients with spinal anesthesia.

2. Objectives

The present study compares the block quality and complications following spinal anesthesia using two different doses of Marcaine and fentanyl in leg fracture surgery among opium abusers.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

The present study was a randomized controlled trial conducted from December 2020 to August 2021 at Vali-Asr Hospital in Birjand.

3.2. Participants

Participants were patients with a history of opium addiction who were candidates for non-emergency leg surgery. Inclusion criteria were age between 15 and 65 years, addiction to opioids, and classification as anesthesia class I or II according to the American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) classification. Exclusion criteria included contraindications for spinal anesthesia, skin infection in the anesthesia area, coagulation problems, surgery duration longer than two hours, change of anesthesia type during the procedure, uncontrolled comorbidity, and known sensitivity to amide anesthetics. The sample size was calculated based on a previous study by Safari et al. (9), with the mean and standard deviation of sedation in the two groups (2.30 ± 2.12 vs. 3.75 ± 2.50), with 95% confidence and 80% power, resulting in 40 subjects in each group using the formula for comparing means in two independent groups. Patients with a history of drug addiction, classified as ASA class I or II, who presented with leg fractures, were selected through convenience sampling. Patients were randomly divided into two groups using block randomization. In this study, the block size was 4, with two participants in each block assigned to group A and two participants to group B.

3.3. Scales

A checklist was designed to include demographic characteristics (age), intervention group, vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate), anesthesia class, level of sensory block, duration of numbness, motor block return time, time of staying in recovery, pain intensity at specific time intervals (1, 2, 3, 4, 8, and 12 hours post-surgery), and complications (nausea, vomiting, headache, itching).

3.4. Intervention

Group A received an intrathecal injection of 3 cc (15 mg) Marcaine and 0.2 cc (10 μg) fentanyl. Group B received an intrathecal injection of 2.5 cc (12.5 mg) Marcaine, 0.5 cc (25 μg) fentanyl, and 0.2 cc distilled water (to equalize the injected volume). Injections were performed in the sitting position with a midline approach using a 25-gauge Quincke-type needle. Spinal anesthesia was administered at the L4-L5 or L5-S1 vertebral levels. Vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate) were monitored regularly. Ephedrine was used for hypotension treatment. Analgesia duration and patient-reported outcomes (nausea, vomiting, headache, itching) were recorded. Pain intensity was measured using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) at specific time intervals (1, 2, 3, 4, 8, and 12 hours post-surgery). Patients with a VAS score ≥ 4 received 30 mg pethidine.

3.5. Data Collection

Checklists were completed by a trained individual. Patients were asked about the presence of complications (e.g., pain intensity, duration of analgesia) up to 12 hours after the operation. This double-blind study ensured that both the surgeon and the patient were unaware of the type of injection administered.

3.6. Data Analysis

The collected data were entered into SPSS software (version 21). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check whether data followed a normal distribution. Data were analyzed using chi-square statistical tests and independent t-tests at a significance level of P = 0.05.

3.7. Ethical Consideration

This research was registered by the ethics committee of Birjand University of Medical Sciences with the code IR.BUMS.REC.1399.167. Informed consent was obtained from all participants

4. Results

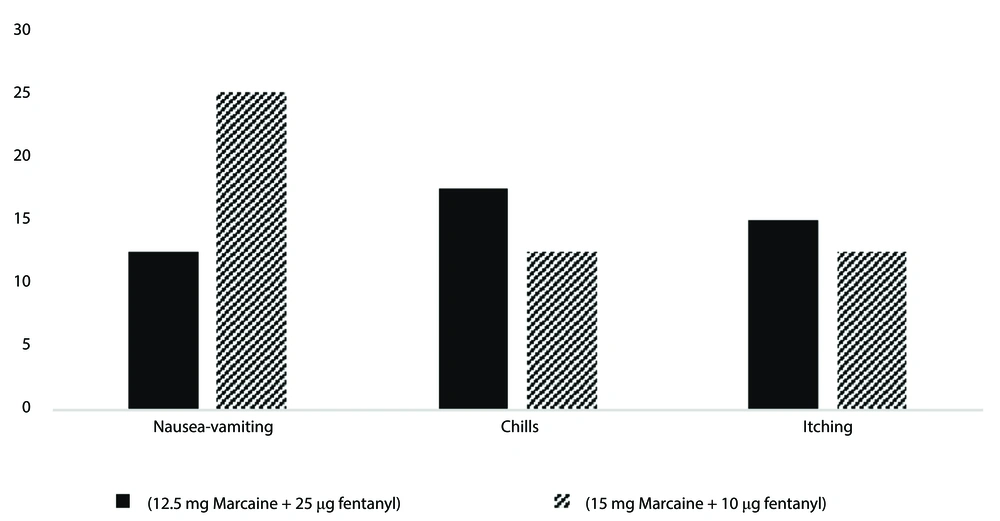

Each group consisted of 40 candidates for leg surgery. The average age of participants was 38.86 ± 13.68 years, with 64 (80%) of participants being male. There were no significant differences in average age, gender, and anesthesia class between the two groups (Table 1). Data analysis with an independent t-test showed that group A (intrathecal injection of 3 cc Marcaine and 0.2 cc fentanyl) had a significantly longer return period of movement block compared to group B (intrathecal injection of 2.5 cc Marcaine, 0.5 cc fentanyl, and 0.2 cc distilled water). Group A also had a significantly longer length of stay in recovery compared to group B (P < 0.001). While group A had a longer anesthesia duration (61.36 ± 20.17 minutes) than group B (54.35 ± 17.18 minutes), the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.67) (Table 1). Group B had a significantly longer analgesia duration (148 ± 27 minutes) compared to group A (90 ± 34 minutes). Group B exhibited significantly lower VAS scores compared to group A (P < 0.001). This difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001) across all examined hours (Table 2). Group A had significantly higher average pethidine consumption compared to group B (Table 2). There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of intraoperative side effects, including nausea and vomiting (P = 0.66), chills (P = 0.65), and itching (P = 0.61), as determined by the chi-square test (Figure 1).

| Characteristics | Group A | Group B | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 40.5 ± 14.24 | 36.55 ± 13.52 | 0.95 b |

| Gender | 0.99 c | ||

| Male | 32 (80) | 32 (80) | |

| Female | 8 (20) | 8 (20) | |

| Class | 0.49 c | ||

| I | 26 (65) | 30 (75) | |

| II | 14 (35) | 10 (25) | |

| Level of sensory block | 0.01 c | ||

| T8 | 9 (22.5) | 1 (2.5) | |

| T6 | 15 (37.5) | 17 (42.5) | |

| T10 | 16 (40) | 22 (55) | |

| Duration of numbness | 61.36 ± 20.17 | 54.35 ± 17.18 | 0.67 b |

| Motor block return time | 115.23 ± 42.71 | 63.35 ± 24.5 | < 0.001 b |

| Time of staying in recovery | 38.24 ± 7.4 | 29.5 ± 7 | < 0.001 b |

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

b Independent t-test.

c Chi-square test.

| Groups | Hour 1 | Hour 2 | Hour 3 | Hour 4 | Hour 8 | Hour 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS | ||||||

| A b | 4.1 ± 0.17 | 3.9 ± 0.15 | 4.1 ± 0.28 | 3.75 ± 0.53 | 3.15 ± 0.23 | 3.3 ± 0.43 |

| B c | 3.2 ± 0.23 | 3.1 ± 0.32 | 3.3 ± 0.54 | 2.48 ± 0.31 | 1.9 ± 0.28 | 0.8 ± 0.33 |

| P-value d | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Petedine dose | ||||||

| A | 15.53 ± 3.57 | 12.41 ± 2.43 | 9.38 ± 2.35 | 5.52 ± 1.90 | 4.25 ± 1.23 | 3.12 ± 0.31 |

| B | 13.30 ± 3.15 | 11.47 ± 3.36 | 8.34 ± 2.22 | 3.11 ± 1.57 | 2.43 ± 0.91 | 1.42 ± 0.84 |

| P-value d | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviation: VAS, Visual Analog Scale.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b 15 mg Marcaine + 10 μg fentanyl.

c 12.5 mg Marcaine + 25 μg fentanyl.

d Independent t-test.

5. Discussion

Combining narcotics with local anesthetics has become a common strategy to improve spinal block quality and reduce postoperative pain. This study compares the block quality and complications after spinal anesthesia using two different doses of Marcaine and fentanyl in leg fracture surgery among opium abusers. Group A (15 mg Marcaine + 10 μg fentanyl) exhibited a significantly longer duration of movement block recovery compared to group B (12.5 mg Marcaine + 25 μg fentanyl). Group B experienced lower pain levels, a reduced need for analgesic drugs, and longer analgesia duration compared to group A. Leo et al. (11) observed that combining narcotics (e.g., morphine) with bupivacaine allows for lower bupivacaine doses while achieving analgesia and preventing complications. Other studies (12-16) also support the effectiveness of bupivacaine for pain reduction after surgery. Adding fentanyl to bupivacaine increases the duration of analgesia, as seen in studies on cesarean section patients (15-17). Other studies also found that the mean duration of anesthesia and analgesia was significantly longer in patients receiving bupivacaine plus fentanyl than in those receiving bupivacaine alone (18). In a study conducted by Ferrarezi et al., the spinal anesthesia technique using 15 µg of fentanyl associated with 10 mg of hyperbaric bupivacaine provided satisfactory analgesia and a very low incidence of adverse effects for patients undergoing cesarean section (17). Safari et al.’s study on addicted patients also highlighted the benefits of combining bupivacaine with fentanyl (3, 9). The duration of motor block return was significantly longer in group A compared to group B (P < 0.05). Ebrie et al. reported that adding fentanyl with a lower dose of bupivacaine in spinal anesthesia for cesarean section could provide comparable anesthesia with a lower risk of hypotension and longer postoperative analgesia (19). Indeed, variations in surgical procedures and drug doses can play a crucial role in the outcomes of different studies. In the present study, there was no difference in nausea and vomiting between the two groups, which is consistent with the findings of Singh et al. and Golmohammadi et al. (20, 21). Akinwale et al. (22) explored intrathecal neostigmine combined with bupivacaine and fentanyl, and similarly reported no significant difference in nausea and vomiting. A meta-analysis by Uppal et al. (23) revealed that adding fentanyl to intrathecal bupivacaine reduced nausea and vomiting during cesarean surgeries. In the study by Shin et al. (24), the incidence of nausea and vomiting during cesarean section was significantly lower in the midazolam-fentanyl group compared to the midazolam-normal saline group. Nausea and vomiting result from a combination of anesthetic and non-anesthetic factors. Blood pressure drop plays a crucial role, but surgical stimuli and increased vagal activity also contribute. To gain more insights, future investigations should explore different fentanyl doses and various surgical scenarios to determine the minimum effective dose for preventing post-surgical complications. In our study, there was no difference between the two groups in terms of shivering and itching. In Sadegh et al.’s study (25), only 10% of patients in the fentanyl group experienced tremors, whereas 75% of patients in the control group had tremors. This suggests that fentanyl may have a protective effect against shivering during spinal anesthesia. Onk et al. (26) found that shivering was significantly less frequent in patients who received morphine and fentanyl compared to the control group. Shivering during anesthesia can result from various factors: Anesthesia affects spinal reflexes, which can lead to shivering; changes in sympathetic nervous system activity may contribute to shivering; adrenal gland function can impact body temperature regulation and shivering. Similar to the present study, Doger et al. (27) did not observe any significant difference in the incidence of side effects between patients receiving bupivacaine alone and those receiving bupivacaine with sufentanil. This suggests that sufentanil, like fentanyl, may not significantly impact shivering or other side effects when combined with bupivacaine. One of the limitations of the study is that due to the small sample size and the specific population (drug addicts), it cannot be generalized to all patients.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings indicate that a higher dose of fentanyl combined with bupivacaine for leg surgery in patients with addiction reduces pain intensity without increasing side effects. Additionally, the need for pethidine was reduced. However, further research is necessary to determine the optimal dosage for anesthesia and narcotics. Future studies could examine the impact of combining various nerve blocks or implementing a wider range of doses.