1. Background

Type 1 diabetes is prevalent among children and adolescents, affecting approximately 1.7 per 1,000 individuals under 20 globally, with an annual incidence increase of 2% to 5% (1). Over 60% of cases occur in Asia (2). In Iran, prevalence ranges from 1.5% to 1.8% in men and 7.4% to 10% in women, with approximately 1 in every 1,000 Iranian adolescents affected (3). Children with diabetes face significant risks, including hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, hospitalization, seizures, coma, and death (4), as well as macrovascular complications (e.g., heart attack, stroke, peripheral vascular disease) and microvascular complications (e.g., retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy) (5). Consequently, a diabetes diagnosis in children is highly stressful for parents (6). Stress, a physiological or psychological response to internal or external stressors (7), can disrupt adaptive parent-child interactions (8). Elevated parental stress levels are often associated with inflexible, threatening, and aggressive parenting behaviors (9). Anger is another emotional response experienced by parents of children with diabetes (10). As a transient emotion and inherent aspect of human personality (9), anger significantly influences human communication. Parental anger can hinder parent-child interactions, negatively impacting the child's development (11). Mothers play a vital role in meeting their children's needs, especially during chronic illnesses (12), and their emotional state directly influences both the quality and quantity of child care (13). Therefore, managing maternal stress and anger is essential.

In Iran, cultural and religious beliefs are deeply rooted (14). Spirituality assists individuals in coping with the intense emotions associated with a child's diabetes diagnosis, often through trust in God and the development of spiritual connections (10, 15). Spiritual health — defined as a form of transcendent communication with a higher power (16, 17) — is linked to enhanced quality of life, greater life satisfaction, and healthier living. Spiritual self-care, as an adaptive coping strategy, involves practices that reduce stress and promote well-being (18, 19). Given the limited number of studies on the impact of spiritual self-care on stress and anger among mothers of children with type 1 diabetes, this study is warranted.

2. Objectives

This study aims to determine the effect of spiritual self-care training on the stress and anger experienced by mothers of children with type 1 diabetes.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

A randomized clinical trial (pre-test-post-test design) with a control group was conducted (IRCT20230426058000N1).

3.2. Participants

The study population comprised mothers of children with type 1 diabetes who attended the Diabetes Center at Imam Reza (AS) Specialized Clinic in Zabol, Iran, in 2024. Inclusion criteria were: Being a native resident (urban or rural), over 18 years old, Persian-speaking and literate, without neurological or mental disorders or known chronic diseases, having a child under 14 with type 1 diabetes for more than six months who cannot independently manage their care, not caring for another patient in the family, and not having faced a new stressful event in the past two months. Exclusion criteria included absence from more than one training session, unwillingness to continue participation, and the death of the participant or their diabetic child.

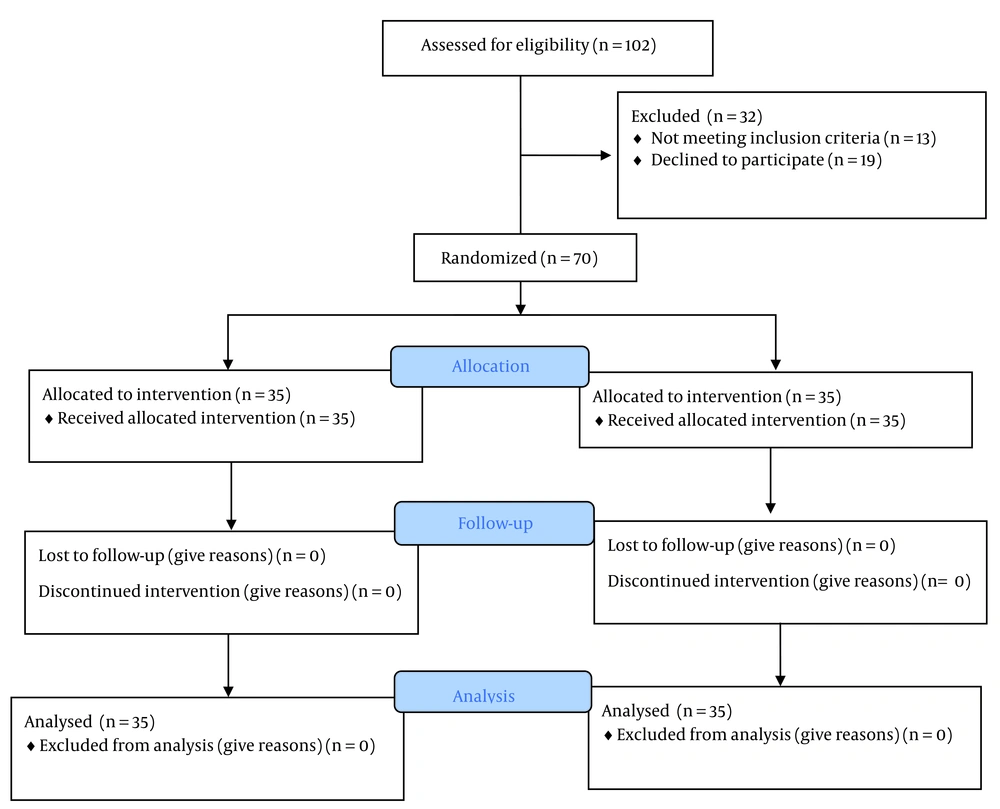

A minimum sample size of 35 participants per group was estimated with 99% confidence and a 15% dropout probability, based on Yazarloo et al.'s study (20). Seventy mothers meeting the inclusion criteria were randomly allocated to intervention (n = 35) and control (n = 35) groups using a lottery method (Figure 1).

3.3. Scale

Data collection tools included:

1. A demographic questionnaire covering age, education level, number of children, occupation, spouse's occupation, economic status, place of residence, religion, child's diabetes background, and participation in entertainment and religious activities.

2. The short form of the Parenting Stress Index, developed by Abidin in 1983, consisting of 36 items across three subscales: Parental disturbance, dysfunctional parent-child interaction, and child-related problems. Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 36 to 180. Validity and reliability have been confirmed (4).

3. The Spielberger Anger Expression Scale, comprising 57 items divided into three sections: State anger, trait anger (with subscales of angry mood and angry reaction), and anger control (with subscales of external anger occurrence, internal anger occurrence, external anger control, and internal anger control). Scoring is based on a 4-point Likert scale, with total scores ranging from 57 to 228. Validity and reliability have been confirmed (21).

3.4. Intervention

The intervention group, in addition to routine care, participated in six 60-minute spirituality-based self-care training sessions (1, 5, 7, 11, 12, 15, 16, 18,20-25) conducted every other day by the researcher (a graduate student) and a professor with a doctorate in theology and Islamic studies. At the end of the sixth session, participants received an educational package containing a booklet and an educational CD (Table 1). The control group received only routine care. During the three-month follow-up, the intervention group received weekly phone calls from the researcher for support and to answer questions. To uphold ethical considerations, the control group was provided with the training package after data collection.

| Session | Content |

|---|---|

| First | Introduction to the work process and goals of the study; Understanding to establish mutual trust and communication between the researcher and the mothers. Distribution and collection of questionnaires to both the experiment and control groups; Question and Answer about their major problems, and exchange experiences |

| Second | Familiarization with spiritual self-care methods, focusing on topics such as trust, patience, altruism, and the afterlife |

| Third | Familiarization with the concepts of spirituality, spiritual methods, and their effects |

| Fourth | Introduction to spiritual methods such as writing memories, talking, reading books, and listening to music |

| Fifth | Introduction to physical methods such as walking and yoga |

| Sixth | Completion of questionnaires three months after the intervention by both the experimental and control groups |

3.5. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS version 23. The Shapiro-Wilk test assessed the normality of quantitative data. Chi-Square or Fisher's Exact test analyzed categorical data, while independent t-tests compared quantitative data. Levene's test assessed the homogeneity of variances.

3.6. Ethical Considerations

Participants received clear explanations about the study's objectives and methods, with assurances of confidentiality and the freedom to withdraw at any stage. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zabol University of Medical Sciences (IR.ZBMU.REC.1402.031).

4. Results

Table 2 shows 70 mothers participated in the study. The average age of mothers in the experimental and control groups was 34.71 and 36.61 years, respectively (P = 0.353). The average duration of the child's diabetes differed significantly between the experimental and control groups (2.63 vs. 3.77 years; P = 0.015). No significant differences were observed between groups regarding the number of children (P = 0.649) or other demographic variables, except for education level (P = 0.013). The Shapiro-Wilk test confirmed the normal distribution of stress and anger scores in both groups before and after the intervention (P > 0.05).

| Variables | Experiment (n = 35) | Control (n = 35) | Z-Score | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | 0.23 | 0.652 b | ||

| City | 19 (54.28) | 21 (60) | ||

| Rural | 16 (45.72) | 14 (40) | ||

| Religion | 0.28 | 0.597 b | ||

| Shiaa | 26 (74.28) | 24 (68.57) | ||

| Sunny | 9 (25.72) | 11 (31.43) | ||

| Education level | 8.75 | 0.013 b | ||

| Primary | 7 (20) | 7 (20) | ||

| Diploma | 25 (71.42) | 15 (42.85) | ||

| Higher education | 3 (8.58) | 13 (37.15) | ||

| Job | 0.068 | 0.0794 b | ||

| Employee | 10 (28.57) | 11 (31.43) | ||

| Housewife | 25 (71.43) | 24 (68.57) | ||

| Spouse job | 0.34 | 0.555 b | ||

| Unemployed | 2 (5.72) | 1 (2.86) | ||

| Worker | 10 (28.57) | 9 (25.72) | ||

| Employee | 8 (22.86) | 6 (17.14) | ||

| Free | 15 (42.85) | 19 (54.28) | ||

| Economic status | 3.29 | 0.224 c | ||

| Weak | 3 (8.57) | 3 (8.57) | ||

| Medium | 28 (80) | 22 (62.85) | ||

| Strong | 4 (11.43) | 10 (28.57) | ||

| Religious activities | 4.01 | 0.127 c | ||

| Low | 22 (62.9) | 29 (82.86) | ||

| Medium | 12 (34.3) | 5 (14.28) | ||

| High | 1 (2.86) | 1 (2.86) | ||

| Entertainment activities | 1.2 | 1 c | ||

| Low | 32 (91.43) | 32 (91.43) | ||

| Medium | 2 (5.71) | 3 (8.57) | ||

| High | 1 (2.86) | 0 |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Chi-Square test.

c Fisher Exact test.

Table 3 shows no significant difference in pre-test stress scores between groups (P = 0.220). Post-intervention stress scores also showed no significant difference (102.25 ± 6.22 vs. 99.25 ± 8.77; P = 0.104). Independent t-tests revealed no significant difference in total stress scores post-intervention (P = 0.104). However, there was a significant difference in the subscale of the characteristics of the problematic child before (P < 0.001) and after the intervention (P = 0.006).

| Variables | Experiment | Control | t-Score | 95% CI Difference | P-Value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental distress | |||||

| Before | 38.71 ± 3.44 | 37.60 ± 3.52 | -1.33 | -2.77,0.54 | 0.185 |

| After | 24.42 ± 3.27 | 27.65 ± 3.86 | 0.05 | -2.87,3.04 | 0.954 |

| Parent-child dysfunction interaction | |||||

| Before | 39.80 ± 3.67 | 39.65 ± 3.67 | -0.16 | -1.89,1.61 | 0.871 |

| After | 32.80 ± 3.40 | 32.31 ± 3.90 | -0.55 | -2.23,1.26 | 0.581 |

| Characteristics of a problematic child | |||||

| Before | 24.42 ± 3.27 | 27.65 ± 3.86 | 3.77 | 1.51,4.93 | < 0.001 |

| After | 31.45 ± 3.89 | 28.88 ± 3.68 | -2.86 | -440,-0.79 | 0.006 |

| Total stress score | |||||

| Before | 102.94 ± 6.940 | 104.91 ± 6.90 | -1.23 | -1.20,5.14 | 0.220 |

| After | 102.25 ± 6.22 | 99.25 ± 8.77 | -1.64 | -6.62,0.63 | 0.104 |

at-independent test.

Table 4 shows that pre-test anger scores were not significantly different (P = 0.880); however, post-intervention anger scores differed significantly between groups (121.28 ± 5.97 vs. 134.20 ± 7.05; P < 0.001). Significant differences were also observed in all anger subscales (P < 0.05), except for external anger control (P = 0.361).

| Variables | Intervention (95% CI) | Control (95% CI) | t-Score | 95% CI Difference | P-Value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angry feeling | |||||

| Before | 9.31 ± 3.25 | 10.02 ± 3.36 | 0.90 | -0.86,2.29 | 0.37 |

| After | 8.11 ± 1.71 | 11.45 ± 1.73 | 8.10 | 2.52,4.16 | < 0.001 |

| Angry mood | |||||

| Before | 10.31 ± 5.48 | 9.94 ± 2.66 | -0.36 | -2.42,1.68 | 0.720 |

| After | 7.74 ± 1.52 | 10.22 ± 1.94 | 5.96 | 1.65,3.31 | < 0.001 |

| Angry reaction | |||||

| Before | 19.51 ± 1.73 | 19.17 ± 1.59 | -0.85 | -1.13,0.45 | 0.394 |

| After | 15.11 ± 2.20 | 16.82 ± 2.12 | 3.31 | 0.68,2.74 | 0.001 |

| Verbal anger | |||||

| Before | 11.97 ± 4.06 | 11.88 ± 3.40 | -0.09 | -1.87,1.70 | 0.924 |

| After | 6.80 ± 1.36 | 9.02 ± 1.50 | 6.48 | 1.54,2.91 | < 0.001 |

| Physical anger | |||||

| Before | 9.11 ± 3.09 | 9.05 ± 3.43 | -0.07 | -1.61,1.5 | 0.942 |

| After | 7.31 ± 1.52 | 9.91 ± 1.86 | 6.36 | 1.78,3.41 | < 0.001 |

| Expressing inner anger | |||||

| Before | 21.54 ± 2.82 | 21.05 ± 2.87 | -0.71 | -1.84,0.87 | 0.478 |

| After | 16.20 ± 2.26 | 18.51 ± 3.24 | 3.27 | 0.89,3.73 | 0.02 |

| Expressing external anger | |||||

| Before | 19.82 ± 2.75 | 20.77 ± 3.47 | 1.25 | -0.55,2.43 | 0.213 |

| After | 15.28 ± 2.23 | 18.62 ± 2.63 | 5.74 | 2.18,4.50 | < 0.001 |

| Inner anger control | |||||

| Before | 20.25 ± 2.59 | 19.88 ± 1.82 | -0.69 | -1.44,0.69 | 0.491 |

| After | 24.94 ± 3.11 | 20.34 ± 2.55 | -6.75 | -5.94,-3.24 | < 0.001 |

| External anger control | |||||

| Before | 19.57 ± 2.29 | 19.17 ± 3.12 | -0.6 | -1.70,0.90 | 0.543 |

| After | 19.77 ± 2.28 | 19.25 ± 2.39 | -0.91 | -1.63,0.60 | 0.361 |

| Total anger score | |||||

| Before | 141.42 ± 11.08 | 140.97 ± 14.02 | -0.15 | -6.48,5.57 | 0.880 |

| After | 121.28 ± 5.97 | 134.20 ± 7.05 | 8.26 | 9.79,16.03 | < 0.001 |

at-independent test.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to examine the effect of spiritual self-care training on stress and anger among mothers of children with type 1 diabetes. The findings revealed that these mothers experienced elevated levels of anger, which is a common psychological reaction to the chronic illness of a child. Such emotional responses are frequently observed among family members of children with diabetes (22). Given that mothers typically assume primary responsibility for diabetes management — including insulin administration, blood glucose monitoring, and dietary regulation — these caregiving duties impose substantial psychological burdens, including stress, anxiety, and anger (2, 7, 8, 23, 26).

The results indicated that spiritual self-care training significantly reduced anger levels in the intervention group. This effect may be attributed to the role of spirituality in fostering inner peace and emotional regulation. Previous studies have also identified spirituality and religious coping as effective strategies for managing psychological distress in families of children with chronic or life-threatening conditions (6, 27). Furthermore, spirituality has been associated with enhanced hope and self-transcendence in mothers of premature infants, highlighting its potential as a tool for emotional resilience and adaptation (28).

Conversely, spiritual self-care did not significantly impact stress levels among participants in this study. While some literature suggests that spiritual health can alleviate psychological disorders — such as stress, anxiety, and fear — in mothers of children with intellectual disabilities (29-31), mothers of premature infants (25), and those with children hospitalized in intensive care units (32), our findings differ. These inconsistencies may be due to variations in study design, cultural context, sample characteristics, or the content and delivery of interventions. It appears that spiritual self-care, as implemented in this study, may not sufficiently address the multifactorial nature of maternal stress, suggesting a need for integrated interventions that combine spiritual, psychological, and practical support.

A key limitation of this study was the potential influence of uncontrolled external sources of spiritual education — such as religious broadcasts, community sermons, or informal media content — which may have affected participants’ spiritual engagement independently of the intervention.

5.1. Conclusions

Spiritual self-care training was effective in reducing anger among mothers of children with type 1 diabetes in this Iranian sample. These findings support the integration of spirituality-based educational programs into the healthcare system and nursing practice. However, the intervention alone was insufficient to reduce stress levels, indicating that additional or alternative support mechanisms are necessary. Future research should explore comprehensive, multimodal approaches to address the complex emotional needs of this population.