1. Background

Adolescence is a critical stage marked by physiological, psychological, and social changes (1). Teenage girls face physical, cognitive, and identity shifts that significantly impact their mental health (2). Self-acceptance, a key issue in adolescent psychology, involves recognizing and embracing one’s abilities, limitations, and choices while maintaining self-respect (3). High self-acceptance correlates with traits like responsibility, emotional awareness, and self-regulation (4), whereas low self-acceptance leads to goal neglect and susceptibility to external influences (5).

Body image, shaped by societal beauty standards and personal perceptions, is closely tied to self-acceptance (6). Poor body image and perfectionism, characterized by unrealistic standards and critical self-evaluation (7), can undermine self-acceptance and exacerbate body image issues (8). Perfectionism, prevalent among teenage girls, influences body image and mental health, with traits like self-criticism and hypercriticism amplifying negative outcomes (9). This pressure often leads to frustration, dissatisfaction, and reduced mental toughness (10).

Negative body image and perfectionism can reduce mental toughness in teenage girls, leading to difficulties with self-acceptance. Mental toughness is the ability to remain resilient under pressure and overcome challenges, which is crucial for the healthy psychological development of adolescent girls (8). When poor body image and maladaptive perfectionism undermine mental toughness, teenage girls become vulnerable to mental health issues, including social anxiety, eating disorders, and depression (11).

Given the increasing prevalence of mental health challenges among adolescent girls, it is imperative to investigate the underlying psychological mechanisms that influence self-acceptance. While prior research has analyzed these factors separately, an integrated model is lacking. The present study fills this gap by employing structural equation modeling (SEM) to analyze these relationships.

2. Objectives

This study employs SEM to explore the relationships between body image, perfectionism, and mental toughness to propose a model of self-acceptance among adolescent girls (12).

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This study is correlational research that utilizes SEM to examine the relationships between variables. The statistical population consisted of second-year female students at Kahnuj High School during the 2023 - 2024 academic year. The study aimed to investigate the interplay between self-acceptance, mental toughness, body image, and perfectionism among this group.

3.2. Participants

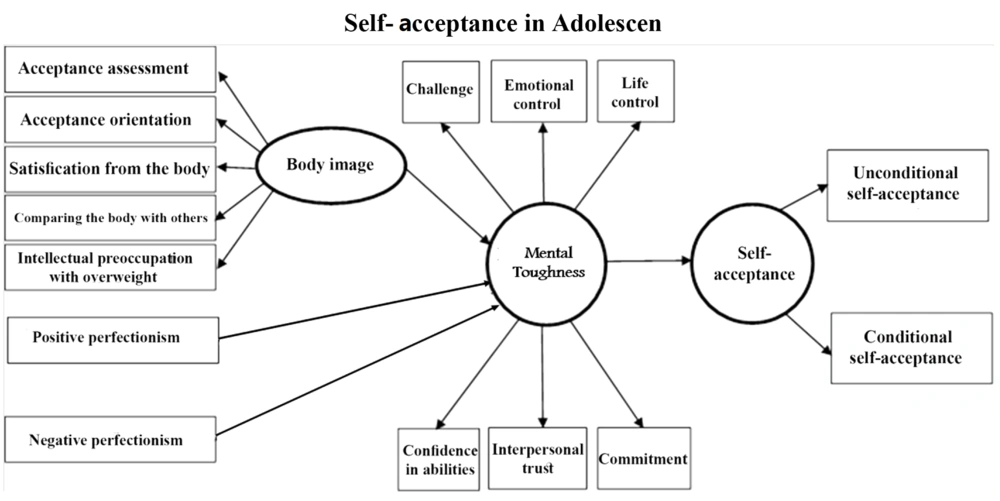

The statistical population for this study comprised second-year female students enrolled in high schools in Kahnuj. All interested female students from girls' secondary schools in Kahnuj who did not report any serious physical or mental illness were eligible to participate. Questionnaires that were returned incomplete were excluded from the final data analysis. Based on the rule that the sample size should be 15 to 30 times the number of observed variables in SEM (13), and considering 16 observed variables (Figure 1), the required sample size was calculated to be 400 students. The samples were selected by a multi-stage cluster sampling method.

3.3. Scales

This study used a 5-part questionnaire to collect data. The reliability of the questionnaire was tested with 20 students outside the sample. Cronbach's alpha value exceeded 0.75, indicating reliability. Content validity was assessed by ten experienced professors.

3.3.1. Demographic Information

This section included age, school name, grade, and study field.

3.3.2. Unconditional Self-acceptance Questionnaire (Chamberlain and Haaga)

This questionnaire includes 20 items scored on a 1-7 Likert scale (from "always false" to "always true") and consists of two subscales (unconditional/conditional). It is suitable for individuals aged 14 and older. Chamberlain and Haaga reported a reliability coefficient of 0.72. In Iran, Shafiabadi and Niknam (14) found an internal consistency of 0.70, while Mazoosaz et al. (15) reported a validity of 0.83. Kalantari (2017) noted a reliability of 0.68. The correlation with Rosenberg's Self-Esteem Questionnaire demonstrated a convergent validity of 0.37 (16). This study found the questionnaire's reliability to be 0.84.

3.3.3. Mental Toughness Questionnaire (Clough, P.J., Earle, K., & Sewell, D., 2012)

This 48-item tool assesses six dimensions (challenge, life control, emotional control, commitment, confidence, interpersonal trust) via a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The questionnaire has shown good reliability, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.87 and a test-retest reliability of 0.90 (17). In Iran, a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93 was reported (18), and factor analysis confirmed construct validity, with all questions having a factor loading above 0.40. In this study, the reliability was found to be 0.87.

3.3.4. Body Image Questionnaire

This is a 56-item self-assessment tool using a 5-point Likert scale (from "very little" to "very much"). It covers five areas: Evaluation of appearance, tendency towards appearance, satisfaction with body parts, comparison with others, and preoccupation with being overweight. Originally developed in 1983 as the Body Shape Questionnaire (BSRQ) with 294 items, its validity was confirmed by Cash et al. in 1990. The reliability coefficient was reported as 0.84 by Cash et al. (19), and 0.89 for Iranian samples. In this study (20), the reliability of the questionnaire was found to be 0.78.

3.3.5. Perfectionism Questionnaire (Short et al., 2010)

This questionnaire includes 40 statements (20 positive, 20 negative perfectionism items) and uses a 5-point Likert scale, where participants rate their agreement from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Previous studies reported Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.81 for positive perfectionism and 0.83 for negative perfectionism (21), with an Iranian study showing a reliability of 0.79 (22). In the current study, the reliability was found to be 0.86.

3.4. Data Collection

Collaborating with the Education Department, schools were divided into four geographic regions, with one school randomly selected per region. Classes were chosen across all fields and grades, yielding 20 classes with 20 students each. Participants provided informed consent and completed anonymous surveys, with data confidentiality assured.

3.5. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SEM with SPSS 25 and Amos 24 software at a significance level of 0.05. Descriptive statistical analysis (mean, standard deviation) and analytical analyses (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, Pearson correlation coefficients, multiple regression, and Sobel test) were performed using SPSS 25. For the chi-square/degrees of Freedom (χ2/df) Fit Index, values less than 5 are considered acceptable, with values closer to zero indicating better model fit. For the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), values of 0.90 or higher are considered indicative of good fit. For the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) Index, values closer to 0.05 indicate good fit, while values above 0.10 suggest that the model may need to be rejected. The conceptual model illustrating the structural relationships between self-acceptance, body image, perfectionism, and the mediating role of mental toughness is shown in Figure 1.

3.6. Ethical Consideration

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Bandar Abbas Branch, under the code IR.IAU.BA.REC.1402.084. The confidentiality of the information of the students participating in the study was assured.

4. Results

A total of 400 students participated in the study: 133 (33.3%) were 16 years old in 10th grade, 169 (42.3%) were 17 in 11th grade, and 98 (24.4%) were 18 in 12th grade (Table 1). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test confirmed that the data followed a normal distribution (P > 0.05).

| Variables | Mean ± SD | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Self-acceptance | ||

| Self-acceptance | 76.91 ± 18.84 | 0.054 |

| Unconditionally self-acceptance | 30.98 ± 10.25 | 0.401 |

| Conditional self-acceptance | 42.07 ± 9.79 | 0.281 |

| Perfectionism | ||

| Perfectionism | 117.39 ± 23.29 | 0.388 |

| Positive perfectionism | 47.23 ± 9.61 | 0.071 |

| Negative perfectionism | 61.78 ± 11.78 | 0.215 |

| Mental toughness | ||

| Mental toughness | 147.81 ± 21.87 | 0.240 |

| Life control | 21.34 ± 4.42 | 0.990 |

| Emotional control | 21.92 ± 4.40 | 0.130 |

| Challenge | 25.02 ± 4.02 | 0.213 |

| Commitment | 3.07 ± 6.31 | 0.063 |

| Confidence in your abilities | 28.31 ± 4.86 | 0.269 |

| Interpersonal trust | 18.15 ± 4.04 | 0.060 |

| Body image | ||

| Body image | 174.74 ± 29.70 | 0.432 |

| Evaluation of appearance | 30.40 ± 4.93 | 0.408 |

| Appearance orientation | 38.01 ± 6.00 | 0.051 |

| Satisfaction from different parts of the body | 62.73 ± 12.18 | 0.071 |

| Comparing the body with others | 12.89 ± 3.23 | 0.066 |

| Intellectual preoccupation with overweight | 36.01 ± 5.27 | 0.110 |

Pearson correlation analysis revealed significant relationships between the research variables (Table 2).

a P < 0.01 correlation at the 99% confidence level.

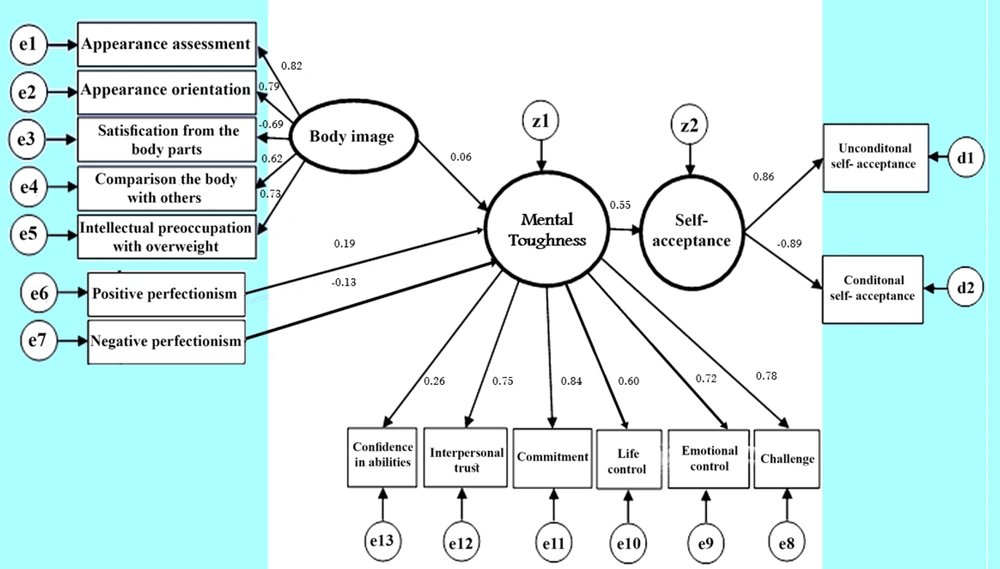

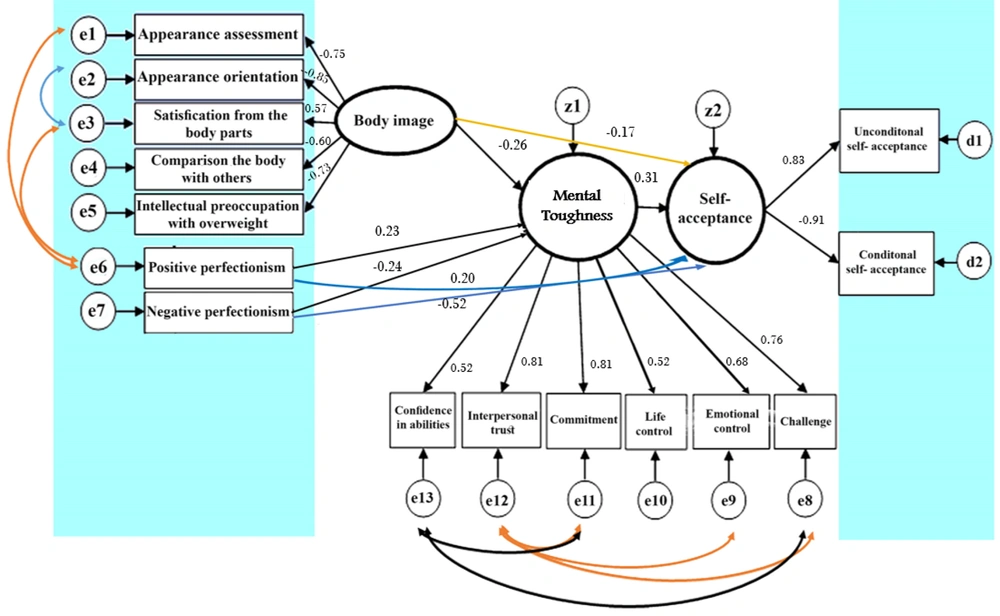

The fit indices for the initial model suggested a poor fit, with high chi-square/degrees of freedom (χ2/df) values and low goodness-of-fit indices (Table 3 and Figure 2). After modifying the model based on the AMOS 24 output and removing non-significant paths, the final model showed significant improvements in model fit, as indicated by the improved fit indices (Table 3 and Figure 3).

| Model Suitability Indices | χ2 | df | χ2/df | NPAR | GFI | IFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developed model | 1307.33 | 88 | 14.86 | 32 | 0.666 | 0.651 | 0.581 | 0.649 | 0.186 |

| Corrected model (final) | 336.26 | 79 | 4.26 | 41 | 0.90 | 0.926 | 0.902 | 0.926 | 0.078 |

| Independence model | 3579.10 | 105 | 34.09 | 15 | 0.344 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.288 |

Abbreviations: df, degree of freedom; NPAR, number of parameters for each model; GFI, Goodness-of-Fit Index; IFI, Incremental Fit Index; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA, Root Mean Square Error Of Approximation.

Regression analysis using the SEM framework revealed significant relationships: Body image was negatively associated with mental toughness (β = -0.26, P = 0.001), while positive perfectionism was positively related to mental toughness (β = 0.23, P = 0.007), and negative perfectionism was also negatively related (β = -0.24, P = 0.004). Furthermore, body image positively influenced self-acceptance (β = 0.17, P = 0.001), as did positive perfectionism (β = 0.20, P = 0.001) and mental toughness (β = 0.31, P = 0.001), whereas negative perfectionism negatively affected self-acceptance (β = -0.52, P = 0.001) (Table 4). Comrey and Lee (1992) established cut-offs for item loadings: 0.32 (poor), 0.45 (fair), 0.55 (good), 0.63 (very good), and 0.71 (excellent). Figure 2 illustrates the initial structural model.

| Path | B | S. E. | β | R2 | t | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body image → mental toughness | -0.053 | 0.019 | -0.26 | 0.068 | -2.80 | 0.001 |

| Positive perfectionism → mental toughness | 0.084 | 0.031 | 0.23 | 0.053 | 2.70 | 0.007 |

| Negative perfectionism → mental toughness | -0.03 | 0.011 | -0.24 | 0.058 | -2.73 | 0.004 |

| Body image → self-acceptance | -0.366 | 0.08 | -0.17 | 0.029 | -4.58 | 0.001 |

| Positive perfectionism → self-acceptance | 0.173 | 0.052 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 3.33 | 0.001 |

| Negative perfectionism → self-acceptance | -0.373 | 0.043 | -0.52 | 0.27 | -8.70 | 0.001 |

| Mental toughness → self-acceptance | 0.751 | 0.101 | 0.31 | 0.096 | 7.49 | 0.001 |

Based on the Sobel test results, mental toughness mediates the relationships between self-acceptance and body image [variance accounted for (VAF) = 0.321] and positive perfectionism (VAF = 0.263), but not negative perfectionism (VAF = 0.126) (Table 5). Figure 3 displays the modified model with improved fit indices following adjustments based on modification indices. The Sobel test confirms that mental toughness significantly mediates the relationships between self-acceptance and both body image and types of perfectionism. According to Hair et al., full mediation occurs when VAF > 80%, partial mediation is indicated by VAF between 20 - 80%, and no mediation is when VAF < 20% (23).

| Variables | a | b | c | Sa | Sb | z | VAF | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body image, mental toughness, self-acceptance | -0.26 | 0.31 | -0.17 | 0.019 | 0.101 | -7.38 | 0.321 | 0.001 |

| Positive perfectionism, mental toughness, self-acceptance | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.031 | 0.101 | 4.85 | 0.263 | 0.001 |

| Negative perfectionism, mental toughness, self-acceptance | -0.24 | 0.31 | -0.52 | 0.011 | 0.101 | -5.08 | 0.126 | 0.001 |

Abbreviation: VAF, variance accounted for.

5. Discussion

This study explored the links between body image, perfectionism, self-acceptance, and mental toughness in adolescent girls. Results showed a significant negative relationship between body image and self-acceptance, aligning with prior research (6, 24, 25). Negative body perception often leads to fixation on perceived flaws, undermining self-confidence and acceptance despite a normal appearance (25). Poor body image weakens self-confidence by fostering obsession over perceived flaws (11). Positive perfectionism correlated with higher self-acceptance, while negative perfectionism related to lower acceptance, aligning with Stoeber et al. (26) and Ferrari et al. (27). Negative perfectionism exacerbates anxiety, shame, and social fear, as individuals set unrealistic goals and react harshly to minor failures (28).

Programs should promote positive body image, self-compassion, and self-esteem. Mental toughness training can enhance self-acceptance, supported by schools and families. The study's limitations include a single-gender focus and lack of socioeconomic analysis. This result is consistent with the findings of Stoeber et al. (26), Cash et al. (24), and Stephenson et al. (25). Due to the higher prevalence of dissatisfaction with body image (29), most previous studies have primarily focused on adolescent girls and adult women. Comparing bodies to societal ideals reduces mental resilience; negative self-image triggers fears of judgment, causing social embarrassment and inadequacy. Judgment fears heighten anxiety, further weakening resilience. Conversely, a positive body image boosts self-worth, optimism, and self-acceptance (13, 30).

In addition, the current study shows that mental toughness mediates the relationship between positive and negative perfectionism and self-acceptance. Positive perfectionism strengthens mental toughness and improves self-acceptance, while negative perfectionism diminishes both (13, 31). These results are consistent with the findings of Stoeber et al. (26) and Ferrari et al. (27), who reported similar relationships between perfectionism, mental toughness, and self-acceptance. Intervention programs should enhance positive body image through media literacy, self-compassion, and self-esteem activities. Mental toughness training can improve self-acceptance, and supportive environments from schools and families are crucial. The study's limitations include a single-gender focus and lack of socioeconomic analysis; future research should address these gaps.

5.1. Conclusions

Positive body image and mental toughness enhance self-acceptance in adolescent girls, while negative perfectionism hinders it. Interventions promoting body positivity, mental resilience, and balanced perfectionism are critical for improving mental health. Schools and families should prioritize programs fostering self-acceptance and well-being, particularly among younger girls from varied backgrounds.