1. Introduction

Silicosis results from prolonged exposure to airborne crystalline silica, which can lead to serious health issues such as lung inflammation, scarring, and breathing difficulties (1). The most common form of silicosis is chronic silicosis, which typically develops after 10 to 30 years of exposure to respirable crystalline silica dust (2). The prevalence of silicosis varies from 3.5% to 54.6%, depending on factors such as the concentration of silica in the workplace, the duration of exposure, and the nature of the job, making it a significant occupational disease that leads to gradual physical disability (1, 3). Professions such as quarrying, mining, glass production (including fiberglass), construction (including cement blasting), agriculture (such as rice milling), and metal manufacturing are associated with increased crystalline silica exposure (3, 4). It should be noted that cigarette smoking damages the respiratory system, resulting in increased susceptibility of smokers to develop silica-associated adverse health effects (5). In recent years, advancements in occupational health regulations have led to a decline in the incidence of pneumoconiosis worldwide. However, in developing nations, including Pakistan, pneumoconiosis, particularly silicosis, continues to be a significant health concern (4). Several challenges in diagnosing and managing these conditions persist, including limited awareness, insufficient resources, and the co-occurrence of tuberculosis (TB), which remains widespread in many developing countries, including Pakistan.

Herein, we report a case of chronic silicosis and active pulmonary TB. The patient had a 30-pack-year history of smoking and a past history of pulmonary TB 4 years ago. He had worked in a stone-crushing factory for the last 35 years. This case report highlights the diagnostic and management challenges of a patient with chronic silicosis and TB, compounded by a history of smoking. It emphasizes the increased risk of TB relapse in individuals with silicosis, particularly in regions with high TB prevalence. The report underscores the importance of early detection, comprehensive treatment strategies, and multidisciplinary care for patients with coexisting silicosis and TB to improve patient outcomes. By focusing on the intricate associations between silicosis, TB, and smoking, the case illustrates the complex interplay of these conditions, especially in individuals with significant occupational exposure to silica. It emphasizes the challenges in diagnosing and managing such coexisting diseases, highlighting the need for timely diagnosis and collaborative care to optimize patient outcomes.

2. Case Presentation

We report the case of a 65-year-old gentleman who presented to the Department of Pulmonology, Bahawal Victoria Hospital, Bahawalpur, with exertional shortness of breath for 6 months. Initially, the patient experienced mild dyspnea during vocational activities, but it had worsened in the last month to the extent that he had dyspnea at rest. This was associated with a productive cough and yellowish sputum for 3 weeks. There was a past history of pulmonary TB 4 years ago, diagnosed via sputum examination, for which the patient had completed a 6-month course of anti-TB therapy comprising isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide, after which he had been declared treated. He was an active smoker with a 30-pack-year history. He had worked in a stone-crushing factory for the last 35 years but was unable to work in the last few months due to his illness. On examination, the trachea was deviated to the right. The left infraclavicular chest area was depressed, showing reduced movements, increased vocal fremitus, bronchial breathing, and increased vocal resonance. Bilateral crepitations were also present.

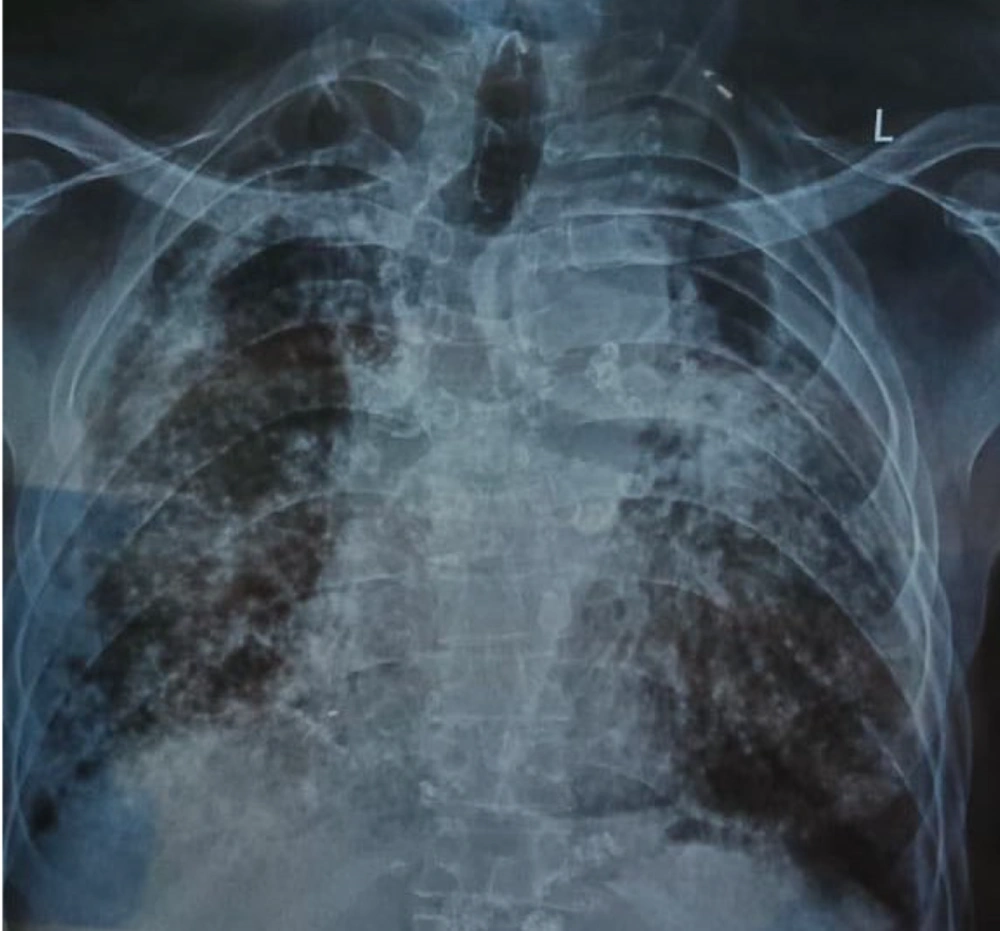

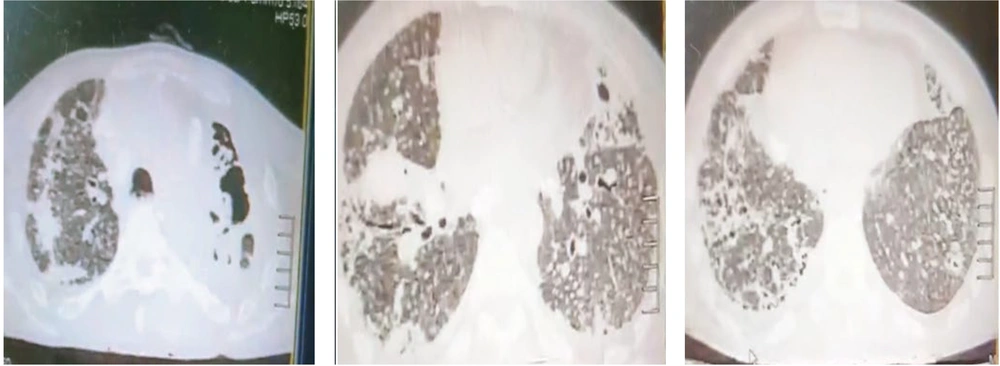

His chest X-ray revealed bilateral reticular shadows and a left-sided apical cavity, as shown in Figure 1. As shown in Figure 2, high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) demonstrated loss of lung volume bilaterally, diffuse nodularity with ground-glass opacifications, bulky hilum, and a left upper lobe fibro-cavitary lesion. Sputum examination was positive for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) stain but negative for Gram stain and pyogenic culture. GeneXpert MTB/RIF PCR confirmed the presence of Mycobacterium TB, but no drug resistance was reported. Based on clinical and radiographic findings, he was diagnosed with active pulmonary TB (relapse) with underlying chronic silicosis by the pulmonology team. For silicosis, supportive therapy and oxygen inhalation therapy were provided. For TB, he was started on category II anti-TB therapy: Streptomycin in addition to isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. Smoking cessation counseling and occupational rehabilitation were also conducted.

3. Discussion

Workers in certain industries face significant exposure to silica and are at an increased risk of developing lung dysfunction and fibrosis. However, large exposures to silica can often go undetected, as it is colorless, odorless, and may not cause immediate symptoms of lung irritation. To diagnose and monitor respiratory health in workers exposed to silica, methods such as chest X-rays, HRCT scans, pulmonary function tests, and health and exposure questionnaires are used, though these approaches may still lead to delayed diagnoses (6, 7). Lung biopsy is considered the diagnostic gold standard, but it is generally avoided unless absolutely necessary due to the risks associated with surgical procedures in silicosis patients (8). There is an elevated risk of pulmonary TB in individuals exposed to silica dust, particularly in those with radiologically confirmed silicosis (9). In areas where TB is endemic, such as South Asia, as many as 25% of silicosis patients also develop TB (10). Additional complications of silicosis can include cor pulmonale and esophageal stress. Silicosis patients have an increased mortality risk from all causes, and the co-presence of TB and smoking is associated with a higher risk (5). Furthermore, silicosis has been reported to increase lung cancer mortality by up to 31% in non-smokers, demonstrating an independent effect of silica on lung cancer risk (5). It should be noted that increased TB risk is seen in active cigarette smokers compared to non-smokers (11). In silicosis patients, a higher mortality due to pulmonary TB has been documented in smokers (5). This greater chance of contracting TB has been linked to the worsening of the host response to infectious agents due to cigarette smoking, in addition to suppression of immune responses due to the direct toxic effects of silica dust and secondary chronic lung inflammation and fibrosis (12).

In this case, a 65-year-old man with a history of occupational silica exposure and smoking developed chronic silicosis and active pulmonary TB. His clinical symptoms, including shortness of breath and productive cough, along with radiographic findings, suggested both conditions. The co-existence of silicosis and TB, compounded by smoking, complicated the diagnosis and management. Smoking likely exacerbated the severity of both conditions, increasing the risk of complications. In the present case, while a lung biopsy could provide definitive confirmation of silicosis, the radiographic findings, including the HRCT scan, were pivotal in suggesting the diagnosis, especially given the patient's prolonged exposure to silica dust. However, due to the overlap in imaging features between silicosis and TB, a consultation with a pulmonologist was essential to confirm the diagnosis and guide appropriate management. Furthermore, in the present case, the patient had a history of pulmonary TB four years ago, for which he was treated and declared TB-negative. However, the patient’s current clinical presentation and positive sputum for AFB and GeneXpert MTB/RIF PCR indicate the presence of active TB, suggesting a relapse despite the past history.

The treatment for silicosis is typically conservative, as the diagnosis is often delayed, and available therapeutic options remain limited. For advanced cases of silicosis, lung transplantation is the primary treatment, as it can extend the survival of patients with severe fibrosis (13, 14). However, lung transplant facilities are not widely accessible in developing countries. Additionally, the procedure is complex, costly, and carries significant risks, including the need for long-term immunosuppressive therapy, with relatively short post-transplant survival rates (14). Other potential treatments being explored for silicosis include large-volume whole lung lavage, pirfenidone, nintedanib, tetrandrine, and some traditional herbal remedies (14). The patient in this case was treated with category II anti-TB therapy, which included streptomycin, isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. Additionally, he received supportive oxygen therapy, smoking cessation counseling, and occupational rehabilitation to manage his chronic silicosis and improve overall lung function. This case underscores the importance of early detection, comprehensive diagnostic evaluation, and multidisciplinary care to improve patient outcomes in individuals with coexisting silicosis and TB, particularly in regions where both are prevalent.

3.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, this case highlights the challenges in diagnosing and managing a patient with coexisting chronic silicosis and active pulmonary TB, particularly in someone with a significant history of smoking and prolonged occupational silica exposure. The patient’s worsening respiratory symptoms and radiographic findings emphasized the need for careful differentiation between silicosis-related complications and a TB relapse. The patient's symptoms and radiographic findings posed diagnostic confusion, as both silicosis and TB share similar clinical and imaging features. Through a comprehensive diagnostic approach, including sputum analysis and HRCT imaging, active TB was confirmed. Early detection and comprehensive management, including both TB treatment and supportive care for silicosis, were crucial in addressing the patient’s complex condition. This case underscores the importance of considering the interplay between silicosis, TB, and smoking in high-risk populations and the need for multidisciplinary care to improve patient outcomes.