1. Background

Adolescent self-harm behaviors represent a critical and escalating global public health issue, with the potential for fatal outcomes such as suicide (1). Adolescents, who face complex developmental and social pressures, are more vulnerable to these behaviors compared to the general population (2). Typically emerging in early adolescence and peaking in mid-adolescence, these behaviors affect millions annually, necessitating immediate intervention (3). Defined as intentional self-destructive acts, regardless of suicidal intent, self-harm significantly impairs adolescent physical and mental health, posing societal risks (4). Risk factors for self-harm include mood disorders such as depression and low self-esteem (5), with a strong association with borderline personality organization, characterized by identity integration deficits and impaired reality testing (6, 7). According to Kernberg’s theory, individuals with borderline personality organization experience identity diffusion, struggling to integrate positive and negative self-representations, leading to emotional and interpersonal instability (8). This instability often results in self-harm as a maladaptive coping strategy, exacerbated by primitive defenses like splitting, which increase emotional volatility (9). Kernberg’s framework describes personality organization as a dynamic structure of internalized object relations, categorized into neurotic, borderline, and psychotic levels, with severe impairments potentially leading to psychotic ideation (10).

Adolescence is a period marked by increased emotional vulnerability, manifesting in risky behaviors such as problematic cyber activity (11). Cyberbullying, a significant contemporary concern, is linked to mental health issues, aggression, and substance abuse (12). It involves various abusive acts, intentionally inflicting harm regardless of age, facilitated by digital platforms (13). Cyber harassment, a pervasive issue, threatens safety and reputation, surpassing traditional forms of harassment (14). Research indicates a strong correlation between cyberbullying, including both aggression and victimization, and self-harm, as well as emotion regulation challenges (15). This underscores the need for focused interventions to mitigate the adverse impacts of cyberbullying on adolescent well-being.

Difficulty in emotion regulation is a critical risk factor for self-harm, encompassing deficits in emotional awareness, acceptance, and coping (16). It involves maladaptive responses to feelings, impairing behavioral control and the use of emotions as information (17). Such deficits increase susceptibility to mental health disorders like depression and anxiety, impacting daily functioning (18). Research consistently demonstrates associations between emotion regulation difficulties and both personality organization and cyberbullying (19, 20). Furthermore, a strong link exists between emotion regulation deficits and self-harm behaviors (21, 22). These findings underscore the importance of addressing emotion regulation in mental health interventions.

Adolescence is a developmental period marked by heightened vulnerability to both internal and external stressors, making it crucial to understand the factors contributing to self-harm behaviors. Given the increasing prevalence of cyberbullying and the established link between personality organization and psychological distress, it is imperative to investigate how these variables interact to influence self-harm tendencies. Furthermore, the role of emotion regulation, a critical factor in adolescent mental health, warrants examination to elucidate the mechanisms through which personality vulnerabilities and cyberbullying experiences translate into self-harm.

2. Objectives

This research aimed to explore the mediating role of difficulty in emotion regulation in the relationship between personality organization, cyberbullying, and the tendency towards self-harm behaviors in adolescents.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This study utilized a descriptive correlational design, concentrating on the population of secondary school adolescents in Tehran during the 2023 - 2024 academic year.

3.2. Participants

A sample of 356 adolescents was selected using a multi-stage cluster random sampling method to ensure representativeness. The sample size adhered to structural equation modeling (SEM) guidelines, which recommend at least 10 participants per estimated parameter. With approximately 30 parameters (e.g., paths, variances, covariances), a minimum of 300 participants was required; however, 356 were included to account for potential incomplete responses and enhance precision. Districts 2 and 13 in Tehran were randomly chosen, followed by the selection of four secondary schools (two male, two female). Three classrooms per school were randomly selected, and students completed questionnaires. Eligibility required current enrollment, no diagnosed psychological conditions or use of psychotropic medication, and informed consent from participants and guardians. Exclusion criteria included unwillingness to participate or incomplete/illegible questionnaires.

3.3. Scales

3.3.1. The Self-harm Behavior Questionnaire

The Self-harm Behavior Questionnaire (SHBQ), developed by Sansone in 1998, is a 22-item self-report tool designed to assess self-harm history using a dichotomous scale (yes = 1, no = 0) (23). It evaluates direct self-harm acts (e.g., cutting, burning, suicide attempts) that cause immediate tissue damage, as well as indirect behaviors (e.g., substance misuse, reckless driving, high-risk sexual activities). Higher scores, up to a maximum of 22, indicate greater severity and frequency of self-harm. Salimi et al. (24) reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.71, suggesting acceptable reliability. In this study, the SHBQ demonstrated strong reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78, confirming its suitability for research purposes.

3.3.2. The Personality Organization Questionnaire

Personality organization was assessed using the 37-item Personality Organization Questionnaire (POQ), a self-report measure developed by Clarkin in 2001 (25). Utilizing a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), the POQ evaluates three dimensions: Primitive psychological defenses, identity diffusion, and reality testing. Total scores, ranging from 37 to 185, indicate the degree of personality disorganization. Monajem et al. (26) reported acceptable internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.76 for primitive defenses, 0.70 for identity diffusion, and 0.73 for reality testing. In this study, the POQ demonstrated reliable internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.76.

3.3.3. The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-Short Form

Emotion dysregulation was measured using the 16-item Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-Short Form (DERS-SF), developed by Bjureberg in 2016 (27). This self-report instrument assesses five dimensions: Lack of emotional clarity, difficulties in goal-directed behavior, impulse control challenges, limited access to effective emotion regulation strategies, and non-acceptance of emotional responses. Items are rated on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = almost never, 6 = almost always). Fallahi et al. (28) reported good to high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.68 to 0.91 across subscales. In this study, the DERS-SF demonstrated strong reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83.

3.3.4. Cyber-victimization Scale

The Cyber-victimization Scale, an 18-item self-report measure, evaluates issues related to cyberbullying (29). It comprises two subscales — cyber aggression perpetration and cyber victimization — rated on a five-point Likert scale (0 = never, 4 = always). Ebrahimi and Khajevand Ahmadi (30) standardized the scale for the Iranian population, reporting high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93 for the overall scale, 0.89 for cyber aggression, and 0.85 for cyber victimization. In this study, the scale demonstrated strong reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87.

3.4. Data Collection

During the 2023 - 2024 academic year, data were collected from secondary schools in Tehran’s districts 2 and 13 using multi-stage cluster random sampling to identify eligible participants. Trained research assistants administered the SHBQ, POQ, DERS-SF, and Cyber-victimization Scale during regular school hours to minimize disruption. Participants received standardized instructions outlining the study’s purpose, voluntary participation, and confidentiality measures. Questionnaires were completed anonymously to ensure privacy and honest responses. Research assistants clarified questions without influencing answers, ensuring accuracy. Completed questionnaires were collected immediately, with incomplete or illegible responses excluded from the dataset.

3.5. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics and Pearson's correlations were utilized, followed by SEM via AMOS 27.0, to analyze variable distributions and test the hypothesized model.

3.6. Ethical Considerations

This study adhered to recognized ethical guidelines and received approval from the Ethical Committee of Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz Branch, under the reference code IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1403.382.

4. Results

This study included 356 adolescents (232 females, 124 males). Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and correlations for personality organization, cyberbullying, emotion regulation difficulties, and self-harm, revealing significant bivariate correlations. Data normality was confirmed with skewness and kurtosis values within ± 2.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1- Personality organization-primitive psychological defenses | 1 | ||||||||||

| 2- Personality organization-identity diffusion | 0.39 a | 1 | |||||||||

| 3- Personality organization-reality testing | 0.66 a | 0.35 a | 1 | ||||||||

| 4- Cyberbullying-cyber aggression | 0.43 a | 0.11 b | 0.12 b | 1 | |||||||

| 5- Cyberbullying-cyber victimization | 0.36 a | 0.11 b | 0.15 b | 0.63 a | 1 | ||||||

| 6- Difficulties in emotion regulation-lack of clarity | 0.45 a | 0.29 a | 0.55 a | 0.39 a | 0.39 a | 1 | |||||

| 7- Difficulties in emotion regulation-difficulty engaging in goal-directed behaviors | 0.40 a | 0.25 a | 0.46 a | 0.26 a | 0.32 a | 0.51 a | 1 | ||||

| 8- Difficulties in emotion regulation-difficulty controlling impulsive behavior | 0.46 a | 0.23 a | 0.37 a | 0.30 a | 0.24 a | 0.59 a | 0.30 a | 1 | |||

| 9- Difficulties in emotion regulation-limited access to effective emotion regulation strategies | 0.50 a | 0.26 a | 0.44 a | 0.31 a | 0.26 a | 0.44 a | 0.56 a | 0.49 a | 1 | ||

| 10- Difficulties in emotion regulation-non-acceptance of emotional responses | 0.49 a | 0.25 a | 0.52 a | 0.25 a | 0.32 a | 0.37 a | 0.45 a | 0.51 a | 0.57 a | 1 | |

| 11- Self-harm behavior | 0.54 a | 0.29 a | 0.59 a | 0.21 a | 0.37 a | 0.33 a | 0.39 a | 0.34 a | 0.41 a | 0.46 a | 1 |

| Mean ± SD | 24.76 ± 6.33 | 22.92 ± 5.14 | 40.46 ± 9.79 | 15.41 ± 4.10 | 16.96 ± 4.18 | 6.77 ± 2.49 | 10.40 ± 3.46 | 9.82 ± 2.68 | 15.85 ± 3.74 | 9.41 ± 2.92 | 6.06 ± 1.88 |

| Skewness | 0.39 | -0.02 | 0.50 | 0.45 | 0.34 | -0.11 | -0.26 | -0.03 | -0.08 | -0.25 | 0.69 |

| Kurtosis | 0.41 | -0.31 | -0.92 | -0.28 | -1.19 | -0.83 | -0.57 | -0.88 | -0.97 | -0.86 | -0.78 |

Means, Standard Deviations, Skewness, Kurtosis, and Correlation Coefficients of Research Variables

Table 2 reports the goodness-of-fit indices for the proposed structural model, evaluating its alignment with the observed covariance matrix. The chi-square (χ2) value was 108.76 with 39 degrees of freedom, resulting in a χ2/df ratio of 2.79, which is within the acceptable range of 1 - 3, indicating a good fit. The Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI) and Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI) were 0.95 and 0.90, respectively, meeting or exceeding the thresholds of 0.95 and 0.85. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) of 0.98 surpassed the 0.95 criterion, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of 0.07, below the 0.08 cutoff, confirmed a close fit to the population covariance matrix.

| Fit Indicators | χ2 | df | (χ2/df) | GFI | AGFI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 108.76 | 39 | 2.79 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.98 | 0.07 |

| Acceptable range | - | - | 1 to 3 | > 0.95 | > 0.85 | > 0.95 | < 0.08 |

Fit Indicators of the Research Model

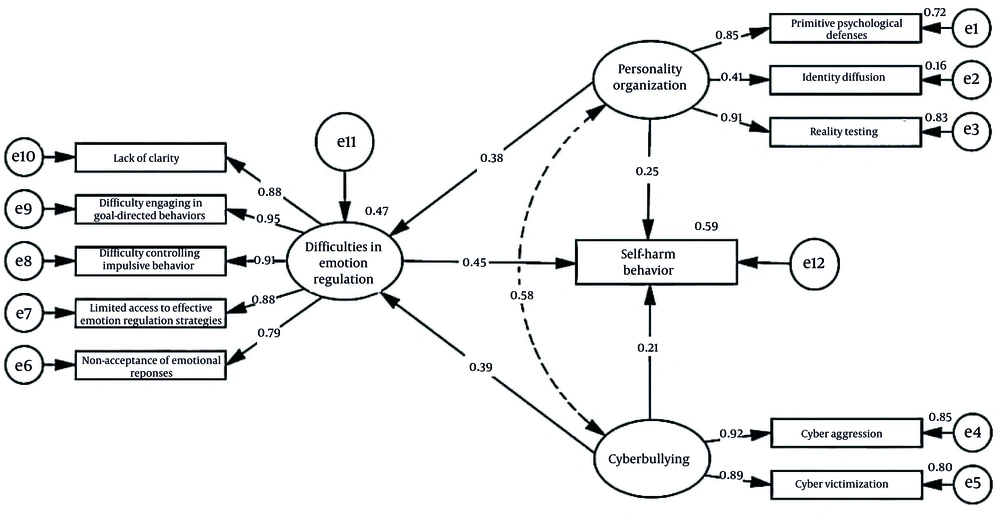

Table 3 and Figure 1 illustrate the direct and indirect pathways in the proposed model of adolescent self-harm. Difficulties in emotion regulation exhibited the strongest direct effect on self-harm (β = 0.45, P < 0.001), indicating that greater dysregulation significantly predicts an increased likelihood of self-harm. Cyberbullying (β = 0.22, P < 0.001) and personality organization (β = 0.25, P < 0.001) also had significant direct effects. Additionally, both cyberbullying (β = 0.39, P < 0.001) and personality organization (β = 0.38, P < 0.001) were associated with emotion regulation difficulties, which mediated their indirect effects on self-harm (β = 0.17, P < 0.001 for both), highlighting their complex interplay.

| Paths | β | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Cyberbullying → difficulties in emotion regulation | 0.39 | 0.001 |

| Personality organization → difficulties in emotion regulation | 0.38 | 0.001 |

| Difficulties in emotion regulation → self-harm behavior | 0.45 | 0.001 |

| Cyberbullying → self-harm behavior | 0.22 | 0.001 |

| Personality organization → self-harm behavior | 0.25 | 0.001 |

| Cyberbullying → self-harm behavior through difficulties in emotion regulation | 0.17 | 0.001 |

| Personality organization → self-harm behavior through difficulties in emotion regulation | 0.17 | 0.001 |

Direct and Indirect Path in the Research Model

5. Discussion

This study investigated the direct and indirect relationships among personality organization, cyberbullying, and adolescent self-harm, with a focus on the mediating role of emotion regulation difficulties. The findings revealed significant positive correlations between cyberbullying, personality organization, and self-harm behaviors. Notably, emotion regulation difficulties significantly mediated the pathways from both personality organization and cyberbullying to self-harm. These results align with previous studies by Anvari and Mansouri (16), Shamsabadi et al. (19), Estevez et al. (20), Clapham and Brausch (21), and Jiang et al. (22).

Research consistently demonstrates a significant positive correlation between cyberbullying and adolescent self-harm, underscoring the detrimental psychological impact of online victimization. Cyberbullying acts as a potent stressor, amplifying emotional distress and promoting maladaptive coping strategies like self-harm (16). Prolonged exposure to hostile online interactions can erode self-esteem and increase social isolation, elevating self-injury risks (20). This is consistent with General Strain Theory, which suggests that negative social experiences trigger emotional strain, leading to maladaptive behaviors. Additionally, Chen et al. (15) found that cyberbullying contributes to self-harm through emotion regulation difficulties, highlighting the critical role of digital environments in adolescent mental health.

The significant positive correlation between personality organization and self-harm behaviors underscores a vital connection between personality structure and maladaptive coping in adolescents. Deficits in personality organization, such as impaired identity integration, interpersonal functioning, or emotional stability, may predispose adolescents to self-injury as a way to cope with internal distress (21). This is consistent with psychodynamic theories that emphasize the role of personality structure in emotional regulation and behavioral outcomes. Reichl and Kaess (6) further support this, noting that borderline personality organization, marked by identity diffusion and emotional instability, strongly predicts self-harm. These findings suggest that underlying vulnerabilities, like impaired self-concept or inconsistent relational patterns, heighten the risk of self-harm under stress.

The significant positive association between emotion regulation difficulties and self-harm behaviors highlights emotional dysregulation as a critical risk factor in adolescent mental health. Adolescents who struggle to identify, modulate, or tolerate emotions are more likely to engage in self-harm as a maladaptive coping strategy to alleviate distress or regain control. This aligns with the experiential avoidance model, which posits that limited emotion regulation skills drive self-injurious behaviors to escape intense emotions (21). Kennedy and Brausch (18) further corroborate this, linking emotion regulation deficits to self-harm and suicidal behaviors in adolescents, emphasizing the role of emotional competencies during this period of heightened emotional reactivity.

Mediation analysis demonstrated that difficulties in emotion regulation significantly mediated the relationships between personality organization, cyberbullying, and self-harm behaviors in adolescents. This suggests emotional dysregulation as a key intermediary mechanism. Deficits in personality organization, such as impaired identity integration or emotional stability, and exposure to cyberbullying may intensify emotional distress, increasing self-harm as a maladaptive coping mechanism (22). This aligns with the diathesis-stress model, where vulnerabilities and stressors interact through emotional dysregulation to drive adverse outcomes. Bansal et al. (13) further support this, showing that emotion regulation difficulties mediate the impact of cyberbullying on mental health. These findings highlight emotion regulation as a vital intervention target to reduce self-harm by enhancing adolescents’ emotional management skills.

While the multi-stage cluster random sampling conducted in Districts 2 and 13 of Tehran was methodologically robust, it imposes constraints on the generalizability of the study’s findings. The focus on urban secondary school students within these specific districts may not adequately reflect the experiences of adolescents across varied socioeconomic, cultural, or rural settings, either within Iran or in other regions.

5.1. Conclusions

This study concludes that personality organization and cyberbullying are significant predictors of adolescent self-harm behaviors. Adolescents with compromised personality organization and those experiencing cyberbullying exhibit increased vulnerability to self-harm. The strong link between difficulty in emotion regulation and self-harm underscores its critical role. Our mediation analysis confirms that emotion regulation difficulties significantly mediate the pathways through which both personality organization and cyberbullying contribute to self-harm tendencies, highlighting the need to address these deficits in interventions.