1. Background

COVID-19 is a new, genetically modified, highly contagious virus from the coronavirus family called SARS-CoV-2 (1). It spread rapidly throughout the world and infected almost all countries in a short period (2). This disease may endanger the mental health status of people (3-5) due to superstitions and misinformation about this pandemic, travel bans, and executive instructions for passengers’ quarantine (6, 7). It may considerably affect patients’ quality of life (QoL) (8). Because QoL, with its various dimensions, aids clinicians in determining problems influencing people’s everyday life (9).

Previous studies on patients with COVID-19 in China during the spread of the disease have reported a high prevalence of several psychological disorders, including anxiety, fear, depression, emotional changes, insomnia, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in these patients (10, 11). In patients with COVID-19, PTSD is one of the most important psychological disorders that can damage their mental health (12).

In stressful situations, people use various coping strategies. They can be classified into 8 subscales: confrontive coping, distancing, self-controlling, seeking social support, accepting responsibility, escape-avoidance, planful problem solving, and positive reappraisal subscales (13). Emotion- and problem-focused strategies are the 2 main coping mechanisms in these situations. The emotion-focused strategies attempt to regulate the emotional consequences of a traumatic event by controlling overwhelming emotions. Problem-focused strategies include activities and responses to remove or alter the source of stress, such as applying cognitive and problem-solving skills. Typically, when people can deal with stressful situations, they use problem-oriented coping strategies, and if they cannot change the case, they might cope with emotion-focused responses (13, 14). Studies have demonstrated individual differences in coping with stress and the association of various coping techniques with health and QoL (15). Determining an appropriate coping strategy is essential to better manage COVID-19 and implement necessary interventions and public health policies; accordingly, we performed this study during the COVID-19 pandemic. In a previous study, during the COVID-19 pandemic, financial security and optimism about the disease increase one’s chances of coping well, while having pre-existing medical conditions and sleeping more than before reduces one’s chances of coping well. They recommended considering their results in planning mental health and public health intervention/policy (16). Earlier studies also suggested that the effectiveness of coping strategies was context-specific and could affect health planning (17, 18).

2. Objectives

According to the importance of COVID-19 as a new concept for medical caregivers, its probable consequences on patient’s mental health/QoL, and based on the importance of assessing the use of diverse methods (such as coping strategies), the present study aimed to assess thoroughly the possible relationship between the QoL of patients with COVID-19 and coping strategies adopted by them.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This cross-sectional study was performed at Imam Reza Hospital in Tabriz City for 2 months, from May 2020 to June 2020. As the Imam Reza Educational Hospital is the primary referral center for patients with COVID-19 in East Azerbaijan, it was chosen to conduct this study. A sample of 70 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 was selected by convenience sampling and based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) COVID-19 patients with a consciousness higher than 12 on the Glasgow scale and (2) the definitive diagnosis of COVID-19 based on the patient’s medical history. Patients were excluded from the study if they refused to complete the questionnaires or if their level of consciousness was below 12 on the Glasgow scale.

3.2. Data Collection Tool and Technique

After obtaining informed consent, the World Health Organization Quality of Life Scale Brief Version (WHOQOL-BREF) and the Coping Strategies Questionnaire (CSQ) were completed, and the demographic characteristics were recorded, including age, sex, education, job, and marital status by patients under the supervision of the researcher.

3.2.1. WHOQOL-BREF

WHOQOL-BREF has 26 items. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale where 1 indicates the lowest negative perceptions and 5 reveals the highest positive perceptions. The score ranges from 26 to 130. To describe the result thoroughly, there is a critical value of 60 as the optimal cut-off point for assessing perceived QoL and satisfaction with health. The first question evaluates QoL in general; this question is called the Single Item Score (SIS), and the second question considers health condition satisfaction. The other 24 questions are grouped into 4 dimensions, including psychological (6 items), social (3 items), environmental (8 items), and physical (7 items) questions (19). In Iran, the validity and reliability of this questionnaire were reported by Taghavi et al. (2014). They mentioned the Cronbach alpha values of ≥ 0.7 in all dimensions (20).

3.2.2. CSQ

In its original version, CSQ consists of 66 items assessing patients’ self-rated use of cognitive and behavioral strategies to cope with daily stress. Problem-oriented coping types consist of seeking social support, accepting responsibility, planful problem solving, and positive reappraisal. Emotional-oriented coping types consist of confrontive coping, distancing, self-controlling, and escape avoidance. Each item in the questionnaire is scored from 0 (I did not use it at all) to 3 (I use it a lot) based on a 4-point Likert scale. Each subscale has a maximum score of 36 and a minimum score of 0. Low, moderate, and high coping strategies are dedicated to 0 - 66, 66 - 110, and > 110, respectively (21). In Iran, the validity and reliability of this questionnaire were reported by Rostami et al (2013). The Cronbach alpha ratio ranged from 0.61 to 0.79, and the test-retest reliability for 4 weeks was 0.59 - 0.8 (22).

3.3. Ethical Considerations

Before the commencement of the study, ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti Medical University (code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1399.674). Online informed consent was obtained from all the participants prior to their participation in this study.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

The variables were described according to the type of variables (quantitative or qualitative) using descriptive statistics (mean, SD, frequency, and percentage). The Pearson correlation test analyzed the relationship between QoL dimensions and coping strategies. All analyzes were performed using SPSS version 21 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill, USA). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

4. Results

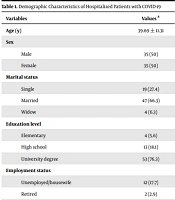

In this study, 70 patients were enrolled, including 35 males and 35 females with a mean age of 39.69 ± 11.31 years (ranging from 20 to 68 years). Among these patients, most of them (66.3%) were married, had a university degree (76.3%), and were employed (80%). Regarding the duration of hospitalization, 54.3% were hospitalized for 0 - 10 days. The detailed demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

| Variables | Values a |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 39.69 ± 11.31 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 35 (50) |

| Female | 35 (50) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 19 (27.4) |

| Married | 47 (66.3) |

| Widow | 4 (6.3) |

| Education level | |

| Elementary | 4 (5.6) |

| High school | 13 (18.1) |

| University degree | 53 (76.3) |

| Employment status | |

| Unemployed/housewife | 12 (17.7) |

| Retired | 2 (2.9) |

| Employed | 56 (80) |

| Duration of hospitalization (days) | |

| 0 - 10 | 38 (54.3) |

| 10 - 20 | 25 (35.7) |

| 20 - 30 | 7 (10) |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD and No. (%).

The results showed that in WHOQOL-BREF, the social dimension had the highest mean score, and the physical dimension had the lowest mean score (65.18 ± 18.99 and 41.40 ± 17.22, respectively). It showed that the social and psychological dimensions had the optimal cut-off point for assessing perceived QoL and satisfaction with health-but the physical, environmental, and general health did not.

In terms of CSQ, the mean scores of problem- and emotional-oriented coping strategies were 87.27 ± 15.45 and 85.05 ± 12.47, respectively. Therefore, patients mostly had higher levels of the problem-oriented coping strategy. The results showed that most participants had moderate problem- and emotional-oriented coping strategies (85.5% and 92.8%, respectively; Table 2).

| Variables | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| QoL dimensions | ||

| Physical | 41.4079 | 17.22972 |

| Psychological | 63.5870 | 15.37010 |

| Social | 65.1882 | 18.99838 |

| Environmental | 53.6305 | 17.72387 |

| General health | 43.5714 | 21.36031 |

| The total score of emotional-oriented coping strategy | 85.0580 | 12.47336 |

| Emotional-oriented coping strategy subscales | ||

| Confrontive coping | 14.5714 | 3.16947 |

| Distancing | 14.0000 | 3.00979 |

| Self-controlling | 18.2714 | 3.30534 |

| Escape-avoidance | 19.0870 | 4.65498 |

| The total score of problem-oriented coping strategy | 87.2754 | 15.45095 |

| Problem-oriented coping strategy | ||

| Accepting responsibility | 10.0429 | 2.71034 |

| Seeking social support | 17.6000 | 3.97602 |

| Panful problem solving | 16.2429 | 3.54039 |

| Positive reappraisal | 19.7714 | 4.31100 |

In addition, there was a direct and significant relationship between physical and general health dimensions of QoL with the problem-oriented coping strategy (r = 0.340, P = 0.005 and r = 0.271, P = 0.025, respectively; Table 3).

aCorrelation is significant at the 0.01 level.

bCorrelation is significant at the 0.05 level.

5. Discussion

This study showed that QoL’s social and physical dimensions had the highest and lowest mean scores, respectively. Besides, most participants had moderate problem- and emotional-oriented coping strategies. It was noted that a higher level of the problem-oriented coping strategy was used than the emotional strategy. It is noteworthy that there was a direct and significant relationship between the score of the physical dimension and the total score of QoL with the problem-oriented coping strategy.

Since assessing QoL is essential due to the long-term lockdown and isolation during the outbreak of COVID-19, recent Chinese investigations have been performed using psychometric instruments (such as Short Form-18(SF-18) (23) and utility instruments (such as EQ-5D-3L) (24). The current study showed that the QoL score was less than 60 out of 100 in 3 main dimensions (possibly due to COVID-19), which was consistent with a previous study (24). Mucci et al. also revealed that the outbreak of COVID-19 had negative impacts on QoL in the general population (25). However, Chen et al., who assessed QoL in China, showed that most of the enterprise workers (93.8%) had a perfect score of 1.000 for EQ-5D during the COVID-19 pandemic (26). These contradictory results may be due to different samples used in these studies. Hospitalized patients were assessed in the current study, but Chen et al. (26) assessed workers during the pandemic.

The current study showed that most of the patients used problem- and emotional-oriented coping strategies moderately, and a high level of using these strategies was noted in limited patients. In a previous study assessing the management of COVID-19-related perceived stress through coping strategies, the results showed that religion (76.3%), instrumental support (51.4%), and active strategies (51.2%) were the most commonly used coping strategies (27). However, a previous investigation on patients with disabilities and chronic diseases mentioned acceptance and self-distracting methods to cope with COVID-19-related perceived stress (28). Also, Altuntaş et al. reported social support as the most frequently used strategy in COVID-19 (29). These different results indicated the importance of considering coping strategies in this pandemic.

5.1. Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, it would be better if the authors could assess a control group from the general population along with hospitalized patients to compare results and show the possible impacts of COVID-19 on QoL and coping strategies. It is noteworthy that comparing the QoL and coping strategies of COVID-19 outpatients with hospitalized one could also be informative. In addition, the authors assessed all hospitalized patients in all age groups. As people’s increased age may affect coping strategies, it is recommended to consider different age groups separately in future studies.

5.2. Conclusions

The current study showed that the QoL score was less than 60 in most of the QoL dimensions in COVID-19. Moreover, most participants used coping strategies moderately, and a high level of using these strategies was noted in limited patients. Therefore, it is recommended to perform further studies to compare the impact of coping strategies on QoL in patients and control groups.