1. Background

Children are the most valuable assets of humanity and, at the same time, the most vulnerable age group (1). The number of infants admitted to NICUs has increased in the last decade. Previous studies have shown that more than half of the infants admitted are term and of suitable weight. However, even full-term infants can be affected by labor complications and maternal stress. In the first days of life, infants can suffer from pathological problems (premature sepsis, respiratory failure, and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy). Among all of these problems, low weight and being preterm play an important role in admission to NICUs (2).

Every year in the United States, more than 19,000 infants die immediately or shortly after being admitted to the NICU. These statistics confirm the restrictive living conditions in NICUs that lead to infant death (3). More than five million infant deaths occur each year worldwide, 99% of which occur in developing countries. The infant mortality rate is an important indicator of health, which reflects economic and social status. The infant mortality rate is 12 - 15 cases per 1,000 births in Iran and five cases per 1000 births in developed countries (4).

Various studies have described the child's death as the worst parental experience (5) that remains fresh even years after the child died and can cause great harm to parents (6). Parents describe the child's death as the most devastating and difficult experience they have ever encountered, destroying all hopes, aspirations, dreams, and plans they had for their child's future, leading to a feeling of shock, numbness, pain, and sensation similar to losing a part of their body (5). The death of an infant is a great loss that may reduce the quality of life of parents and cause severe psychosocial reactions (7). Parents of children admitted to pediatric and neonatal intensive care units are at increased risk for post-traumatic stress disorder. Thus, palliative care may improve these consequences for parents (8).

Currently, physicians and nurses face a new challenge in neonatology, especially in end-of-life care and palliative care. The goal of end-of-life care is to prevent infant pain and provide support for the parents and involve them in decision-making for infant care. Palliative care decisions should involve physicians, nurses, parents, and the team that should support the family after the infant dies (9).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined palliative care as an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other physical, psychosocial, and spiritual problems (10). Palliative care is a relatively new specialty in medicine, especially in pediatrics. The American Academy of Pediatrics describes the purpose of palliative care as relieving suffering, improving quality of life, facilitating informed decision-making, and helping coordinate care between physicians and other care centers. The American Academy of Pediatrics also recommends that palliative care be available to all children with life-threatening conditions (3). The American Academy of Pediatrics and the National Association of Neonatal Nurses also recommend palliative care as standard care in the neonatal intensive care unit. Furthermore, establishing a multidisciplinary team of palliative care professions can improve outcomes for infants and families of infants admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit with a life-threatening disease (11).

A quantitative study examined Iranian NICU nurses' attitudes toward palliative care and its barriers using the Frommelt Attitude Toward the Care of the Dying Scale (FATCOD) and Palliative Care Attitude Scale (NiPCAS). The results showed that nurses had positive attitudes toward palliative care. A strong obstacle to providing palliative care was the inappropriate use of technology. The organizational culture and professional competence of the nurses were at the moderate level, and the weak barrier to implementing palliative care was the nurses’ personal and social attitudes (12). A review study reported that one of the major barriers to providing palliative care is the lack of a suitable physical environment. The researchers recommended that palliative care in the NICU be provided in an environment that allows for parents’ privacy and comfort. The WHO emphasizes that palliative care is essential for infants and that barriers to palliative care must be removed so that nurses can provide palliative care with the same skills and enthusiasm as other caregivers (13). A qualitative study in Australia examined NICU nurses' perceptions of barriers and facilitators of palliative care. The results showed that staff training, lack of privacy, isolation, staff characteristics, and systemic factors (policies and procedures) affect palliative care delivery. These were considered barriers to providing quality palliative care in the NICU (14). Al-Hajery et al. highlighted cultural and religious limitations, lack of a palliative care team, and insufficient knowledge as the main obstacles to palliative care in the neonatal and pediatric intensive care unit (15). Evidence shows that nurses face many barriers and challenges in providing palliative care. Thus, identifying these barriers is an essential step in providing palliative care (12).

Carter noted the importance of qualitative research in palliative care for infants and toddlers (16) as palliative care in the pediatric and neonatal intensive care units can be different (15). Thus, based on these arguments and given the importance of providing palliative care in NICUs, it is necessary to study palliative care and its barriers in NICUs. Several studies have addressed barriers to palliative care. However, since these barriers can vary in different cultures and nurses are at the forefront of providing palliative care, and following the instructions of the Neonatal Health Department for providing palliative care in NICUs, it is essential to identify barriers to palliative care.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to explore nurses’ experiences of palliative care barriers in NICUs. Furthermore, given that qualitative research is used to less-known phenomena and issues about which there is little information, the barriers to palliative care in NICUs were investigated through a qualitative study.

3. Methods

Since the present study aimed to discover nurses’ experiences of barriers to palliative care in NICUs, the conventional qualitative content analysis method was used. Content analysis is a research approach that aims to provide new knowledge and improve the researcher's understanding of phenomena (17). The research population included all nurses working in NICUs. The research setting was NICUs in Isfahan medical centers.

The participants were selected using purposive sampling. In this method, the researcher selects the participants who have rich information (18, 19). The participants in this study were the nurses who had palliative and end-of-life care experience for infants and families. After obtaining the necessary permits and informed oral consent from the participants, the researcher conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews with the participants in their free time (after the end of the work shift) and places selected by them (usually empty spaces in the ward or hospital). Additional interviews were conducted with two nurses, and no new data were added to the previous data and the data were saturated. Each interview lasted 25 - 50 minutes. Each interview began with a general question (e.g., please tell me about your experience caring for a baby at the end of life) and proceeded with more in-depth questions (e.g., what are your experiences with palliative care for infants? or could you please explain barriers you faced in providing palliative care?).

In this study, at the first step for coding the data, the audio files of the interviews were transcribed word by word using Lyric Maker Software and typed using Microsoft Word and coded. Data were analyzed simultaneously with the data collection process using conventional qualitative content analysis conducted inductively with Graham and Lundman’s approach. The data were analyzed using the following steps: extracting the units of analysis, identifying meaning units, condensing and abstracting the meaning units, extracting the codes, subcategories, and categories, and forming themes (20).

In the first step, the units of analysis were identified. In general, data in content analysis are in written and textual form. Each interview as a whole can be considered a unit of analysis, as was the case in the present study. In the second step, the meaning units or codes were determined. A meaning unit is a textual unit that is to be categorized during analysis. In the present study, the statements in the interviews were selected as meaning units based on the message in the text. In the third step, the meaning units were condensed, and the codes were abstracted. Condensation means reducing the volume and size of the text while maintaining the original concept therein. With the process of reduction and condensation, condensed, meaning units are formed. In the fourth step, the codes were categorized into subcategories. After the codes were formed inductively, the similar codes were merged into some subcategories based on their features, characteristics, and criteria related to the meaning of the codes.

In the fifth step, the categories were extracted from the subcategories. To this end, the subcategories were compared, and those representing a concept were placed in a category. Thus, the main categories were formed by grouping the subcategories based on their similarities and differences. In the sixth step, the themes were extracted from the categories based on the characteristics and dimensions of the categories and subcategories.

In the present study, content analysis was performed inductively. Inductive content analysis is often performed in cases where there are no previous studies on the phenomenon or the time they occur. This type of analysis involves the processes used to extract categories or themes from raw data based on valid inference and interpretation. Therefore, if there is not enough prior knowledge about the new phenomenon or this knowledge is derived using an inductive approach, the categories must be derived from the data using inductive content analysis (17).

Guba and Lincoln’s criteria were used to establish the rigor of the study (21). To ensure the credibility of the findings, the participants were selected with maximum variation in terms of age, work experience, and education. The data were confirmed using member checking and peer checking by the participants and experts. To enhance the dependability (consistency) of the in-depth semi-structured interviews, the procedure taken to collect and analyze the data was recorded and described in detail. Furthermore, to ensure the confirmability of the data, the interviews were recorded, and all the steps taken to conduct the study were reported in full detail so that potential readers can review the research procedure if necessary. Finally, to enhance the transferability of the findings, the data and the results were reviewed by some people with characteristics similar to those of the participants, and they judged and confirmed the results based on their experience. Furthermore, the results of this study were compared with similar studies in the literature.

This study was conducted with full compliance with all ethical principles and considerations, and it was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee with the code of ethics IR.IAU.KHUISF.REC.1398.135. In addition, the researcher obtained informed consent from the participants and got their permission to record the interviews. The participants were told that they could leave the study at any stage if they wished. They were also reassured of their privacy, the confidentiality of their information, their anonymity in data analysis and reporting the results, and receiving advice from a consultant if they faced any mental problem during the study.

4. Results

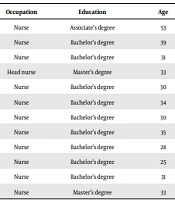

The participants in this study were 12 nurses with a mean age of 33.5 ± 2 years. The descriptive statistics for the participants’ demographic characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

| Participant code | Occupation | Education | Age | Gender | ICU Records (y) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nurse | Associate’s degree | 53 | Female | 20 |

| 2 | Nurse | Bachelor’s degree | 39 | Female | 8 |

| 3 | Nurse | Bachelor’s degree | 31 | Female | 3 |

| 4 | Head nurse | Master’s degree | 33 | Female | 7 |

| 5 | Nurse | Bachelor’s degree | 30 | Female | 4 |

| 6 | Nurse | Bachelor’s degree | 34 | Female | 7 |

| 7 | Nurse | Bachelor’s degree | 30 | Female | 3 |

| 8 | Nurse | Bachelor’s degree | 35 | Female | 6 |

| 9 | Nurse | Bachelor’s degree | 28 | Female | 2 |

| 10 | Nurse | Bachelor’s degree | 25 | Female | 1 |

| 11 | Nurse | Bachelor’s degree | 31 | Female | 5 |

| 12 | Nurse | Master’s degree | 33 | Female | 4 |

The Participants’ Demographic Characteristics

4.1. The Categories Extracted from the Qualitative Step

Using an inductive approach, a total of 350 codes were extracted from 582 primary codes from 12 interviews. The extracted codes were further classified into three main categories, including unfavorable conditions (subcategorized into “unsuitable physical environment” and “shortage of nurses”), nurse's mental problems (with the subcategories of “nurses’ mental problems in providing neonatal care” and “nurses’ mental problems in providing family care”) and the challenges ahead (with the subcategories of "parental presence challenge” and “doctor's instructions challenge”) (Table 2).

| Theme | Categories | Subcategories |

|---|---|---|

| Barriers to palliative care | Unfavorable conditions | Unsuitable physical environment |

| Shortage of nurses | ||

| Nurses’ mental problems | Nurses’ mental problems in neonatal care | |

| Nurses’ mental problems in family care | ||

| Challenges ahead | Parental presence challenge | |

| Doctor’s instructions challenge |

The Categories and Subcategories Extracted from the Qualitative Data

4.2. Unfavorable Conditions

The results showed that unfavorable conditions were categorized into “unsuitable physical environment” and “shortage of nurses”.

4.2.1. Unsuitable Physical Environment

One of the concerns of the participants in this study was the unsuitable physical environment to provide emergency care and palliative care. Most of the nurses stated that the neonatal intensive care unit was very stressful due to the unsuitable physical environment, crowdedness, and a large number of different devices in the NICU. They also pointed out that this congestion could be an obstacle to providing palliative care. One of the nurses stated:

“The unavailability of enough space to separate a critically ill infant is really problematic. To be able to take care of a critically ill infant quickly, sometimes you have to go through couches, nurses, mothers, and even students to do the right thing in this situation” (Participant #6).

Another contributor stated:

“We do not have a separate space to keep and care for dying babies so that the rest of the mothers do not see them. If there was a space for end-of-life care and relief where other mothers could not see it and get disturbed, it would be great. If only we had it” (Participant #1).

4.2.2. Shortage of Nurses

According to the nurses in this study, the shortage of nurses was another problem and difficulty in performing palliative care in the neonatal intensive care unit. One of the nurses said:

“I think when there are more nurses, we can do our job better with less stress. Most of the time, due to the shortage of staff, we have to do the work typically done by several people. Sometimes parents complain about why no one answers their questions and why the nurses do not explain to them what to do ... They are right, but sometimes, we are so busy that we have no time left for families. How should we take time for palliative care with this huge workload and the shortage of staff???” (Participant #5).

4.3. Nurses’ Mental Problems

The nurses’ mental problems were subdivided into “nurses’ mental problems in providing neonatal care” and “nurses’ mental problems in providing family care”.

4.3.1. Nurses’ Mental Problems in Providing Neonatal Care

In this study, a majority of the nurses stated that caring for a baby at the end of life is very difficult and has caused many psychological problems for them. Most of the nurses complained of discomfort when faced with the difficult situation of the infant and parents, and saw it as an obstacle to providing effective palliative care. One of the participants stated:

“We know that most of the babies admitted to the NICU are in critical condition, and there is very little hope for their returning to life, and they probably spend the last hours or minutes of their lives and need palliative care. We also have children, and we suffer a lot psychologically, and it is wrong to think that this situation will become normal for us and we never get used to it” (Participant #8).

Witnessing the death of an infant is one of the psychological traumas that nurses face. Most of the nurses participating in this study pointed to the psychological traumas that they had suffered due to the death of the infant, and it had even affected the lives of the nurses for a long time. According to one of the participants:

“After working in this department for a few years, when such a small baby dies, it affects me so much that I cannot stop thinking about it at all for even a few days and sometimes even a few months. Everything I do and everywhere I go, I remember the scene of that child dying. When I see a baby die before he/she experiences his/her mother’s arms, I really undergo a lot of psychological distress” (Participant #5).

4.3.2. Nurses’ Mental Problems in Providing Family Care

Another important problem in palliative care was the psychological harm experienced by nurses when taking care of infants in the last stage of life and providing palliative care due to the painful reaction of the family, especially the mothers’ reaction to their infants’ death. Pointing to the negative impact of the parents’ reaction, especially the mother of the infant who is in the last stage of life, one of the participants stated:

“The fact that we cannot control ourselves mentally is a factor that does not allow us to help families in this situation. I cannot even imagine being in the place of those parents and I cannot stand it at all. May God help them. Sometimes I wonder how is the feeling of these families in this terrible situation. I think this is the most painful feeling a mother can experience in life. Witnessing this situation every day is very painful and negatively affects us” (Participant #5).

One of the nurses also described the psychological stress caused by parental stress as follows:

“Sometimes I cannot sleep well at night, and I dream about the scenes I saw in the ward during the day and I am stressed all the time. For example, I cannot forget a mother crying or complaining about her life and destiny and scenes like that. It is very hard for me to forget a mother is crying over her baby's dead body, I do not know how I should have helped them” (Participant #3).

One of the main concerns of the participants in this study was facing parents who did not accept infant death or palliative care. One of the nurses described her experience as follows:

“Some parents do not accept their child’s death and shout and break things. In these cases, the nurse must be patient; however, she is very emotionally affected” (Participant #12).

4.4. Challenges Ahead

The challenges faced by the nurses in providing palliative care were the parental presence challenge and the doctor’s instructions challenge, as discussed below:

4.4.1. Parental Presence Challenge

Some nurses referred to the problems caused by the presence of parents in the NICU. One of the nurses described her experience of parental presence as follows:

“Painful medical procedures such as frequent venipuncture and blood sampling, repeated suctions, inserting nasal tubes, etc. for infants disturb the parents’ feelings and they may react differently when seeing these procedures” (Participant #10).

Another participant commented on the impact of family preparation:

“We have to help the parents to see the baby, we have to give them the necessary explanations, and we have to prepare them. It can be very effective if the parents can see the baby and engage in making decisions about him/her. This helps them accept the baby's condition and improves parental adjustment and the provision of palliative care for the baby” (Participant #1).

4.4.2. Doctor's Instructions Challenge

The nurses participating in this study stated that lack of authority and the need to obey a doctor's orders sometimes affect their work. The nurses needed a physician's order to provide palliative care. One of the nurses stated:

“Unfortunately, we do not have much authority in palliative care and we must obey the doctor's instructions. For example, if we are ordered to take blood from a dying baby, we must do it; otherwise, we will be blamed later” (Participant #7).

Another nurse added:

“Because we are nurses, we cannot help much, and we cannot act against the doctor's opinion. Sometimes we can convince the doctor to provide palliative care, but sometimes we cannot. Most of the time, I try to do what I think is right, but the circumstances do not always allow me to do that” (Participant #2).

5. Discussion

The present study showed that the barriers to palliative care were unfavorable conditions, nurses’ mental problems, and the challenges they faced. Most neonatal intensive care units did not have a separate place for palliative care. Furthermore, the shortage of nurses made it a priority for nurses to provide care to infants who were in better condition and hoped to improve.

Barriers to palliative care in the NICU include any disruption to the implementation of a palliative care model. These barriers take different forms and are not the same in different cultures. A cross-sectional study examined barriers to palliative care in Iran and showed 42.63% of the nurses reported inadequate facilities, untrained nurses, and social attitudes as the main barriers. Other barriers were ineffective organizational culture and insufficient nursing skills (22). Other studies have reported failure to provide post-mortem care, parental distress, lack of medical staff, and poor physical environment in the neonatal intensive care unit as barriers to palliative care. The existence of distress and unsuitable environment are other factors mentioned. Several nurses stated their main problem was not knowing when to talk about palliative care with the family of a patient with an unknown prognosis (3). Other studies reported the barriers to palliative care in the neonatal intensive care unit include lack of staff training, lack of preparation, disturbing physical space, language problems, and caregiver emotional distress. Several nurses considered the turbulent physical environment of the neonatal intensive care unit to be a barrier to a quiet death. Nurses and parents stated that the existence of palliative care clinical guides as facilitators of palliative care (23). In Kilcullen’s study, nurses mentioned the lack of up-to-date training in palliative care as one of the barriers to providing palliative care (14). In another study, of 192 neonatal intensive care nurses and physicians, only 21% were trained in end-of-life palliative care (15). The need for further improving the positive attitude of nurses by holding clinical and theoretical training courses as well as paying more attention to eliminating barriers have been mentioned as factors that can enhance the quality of palliative care (12).

In line with the present study, various studies have pointed to unfavorable conditions and the shortage of nurses as the main barriers to palliative care. However, concerning the shortage of nurses, the ratio of nurses to beds was not estimated in this qualitative study. Nevertheless, other qualitative studies highlighted the lack of facilities and insufficient skills of nurses as barriers to palliative care in Iran, but the nurses in the present study complained more about the insufficient number of nurses.

Nurses who are involved in infant and family palliative care experience many psychological problems, and thus, they need to be supported to maintain their health. For palliative care for infants, nurses who are constantly exposed to work-related emotional distress in end-of-life care require more support (9). Employee support can help reduce emotional stress. Nurses and physicians involved in palliative care in the neonatal intensive care unit pointed to shared needs to improve the ability to provide palliative care. These needs include emotional support from staff, organized palliative care, specific guidelines for prescribing palliative care for infants, and further training in this area. Moreover, holding discussion sessions after the baby’s death reduces the burden of the problem and helps as emotional support for adjustment (23). As pointed out above, various studies have emphasized the importance of paying attention to the psychological problems of nurses involved in palliative care and supporting them to perform palliative care in neonatal intensive care units.

The present study showed that one of the challenges for nurses was whether parents should present at the infant bedside during palliative care. Moreover, sometimes the doctor ordered aggressive actions for the dying baby and challenged the nurse. Providing palliative care in the neonatal intensive care unit is challenging because there are uncertain cases in diagnosis and prognosis. It is difficult to ensure that sufficient opportunities are available for the parents both before and after the death of their child (24). Nevertheless, nurses and physicians have a moral obligation to provide palliative care for the child and parents (23). Recently, researchers have recommended that palliative care be considered from the earliest stages of end-of-life care and mourning. The time to start this care should be selected based on the client's needs instead of considering the prognosis while taking into account the obstacles to effective palliative care in the neonatal intensive care unit (25).

In the present study, the nurses reported many challenges they faced in palliative care, including neonatal pain control and physician instructions. Cerratti et al. also found that people involved in palliative care for infants are more likely to experience emotional and moral distress and that their attitudes toward end-of-life care can greatly affect their ability to adapt to this situation. Italian nurses experience many ethical dilemmas regarding palliative care (9). In a qualitative study, ethics, beliefs, and values were found as important factors in providing quality palliative care. Nurses reported the need for critical reflection on their ethics, values, and beliefs when providing quality palliative care (14).

A study on pain control in UK hospitals showed most infants receive palliative care after the stoppage of advanced care. They often received sedatives and painkillers through the central or peripheral arteries. If they did not have a suitable vessel, the drugs were administered intragastrically or subcutaneously (24). In another study, families’ perceptions of end-of-life care were assessed through a questionnaire. The results showed that parents had a conflicting understanding of the performance of care providers. Only less than half of the parents felt that their baby was cared for well (26). In children with a life-threatening illness, the parents may want to move the child home, given all the facilities and 24-hour access may be feasible for some families (24). If a child with a life-threatening illness wishes to be discharged from the ward and cared for at home, the child’s treatment plan must be preplanned with all treatment teams available so that the parents can participate in the treatment plan (24).

As indicated in various studies, palliative care is associated with many challenges. Studies have not addressed the challenge of parental presence, and it has often been believed that parents can be present at the infant bedside and even engage in infant-related decisions, but given the cultural context prevailing neonatal intensive care units in Iran, nurses sometimes did not consider the presence of parents necessary. However, previous studies have identified other challenges, such as caring for a baby at home, that were not addressed in the present study. Having a clear clinical guide can also alleviate the challenge of parental presence and doctor's instructions. By removing the existing barriers to the implementation of palliative care in neonatal intensive care units, it is possible to provide great assistance to families with infants at the end of life and death and to alleviate their pain to some extent. One of the limitations of the present study was its coincidence with the COVID-19 pandemic, making conducting the interviews more difficult and lengthening the duration of the study.

5.1. Conclusion

The results of the present study showed that it is necessary to have suitable physical conditions and sufficient nurses to perform palliative care in neonatal intensive care units. Besides, paying attention to the mental condition of nurses and the problems they face in providing end-of-life and palliative care for infants and families, implementing a free counseling program, and granting incentive leave after palliative care are recommended. Furthermore, there should also be a specific program to address the challenge of parental presence and the doctor’s orders to implement a successful palliative care program in neonatal intensive care units. Thus, the insights from this study need to be taken into account in providing palliative care with a family-centered approach.