1. Background

Patients are one of the most vulnerable social groups because a patient, in addition to physical weakness, also suffers from psychological, social, and economic pressures (1, 2). Thus, international human rights organizations pay special attention to the concept of patient rights (3). The American Hospital Association (AHA) Patient’s Bill of Rights, published in 1973, initially listed 13 rights and became a widely used model for American hospitals. In 1991, the British government published the Patient’s Bill of Rights in the form of a booklet outlining patients’ rights to care in national health services (4). In Iran, the Patient’s Bill of Rights was drafted in 2002 and sent to affiliated centers by the Deputy Minister of Health of the Ministry of Health, Treatment, and Medical Education (2). Patients’ rights refer to specific legal privileges related to physical, psychological, spiritual, and social needs that have been reflected in the form of medical standards, rules, and regulations, and the health system and medical staff are responsible for their observance (5). The purpose of the Patient’s Bill of Rights is to defend human rights, preserve their dignity and honor, ensure nondiscrimination based on race, age, sex, and financial status, and protect the body and soul of the patient (6).

In Iran, the Comprehensive Patient’s Bill of Rights was drafted in 5 core sections with insight and value and a final note. The 5 sections of the charter highlight the right to receive desirable services, the right to receive health services, the right to receive information desirably and sufficiently, the right to freely choose and decide on receiving health services, the right to respect patients’ privacy, and the principle of confidentiality, and the right to access an efficient grievance redressal system (7, 8). The Patient’s Bill of Rights improves the quality of health care and communication between patients and health care staff. Although the bill has been widely emphasized by health system policymakers, it is still a vague concept for patients and health care providers (9). Gholami et al. showed that from the patients’ perspective, the rate of the observance of patients’ rights in the Emergency Department of Shiraz Namazi Hospital was 51% (10). Furthermore, Parniyan et al. reported that the mean score of operating room technicians’ knowledge about patients’ rights was 19.54 out of 24 scores with a standard deviation of 3.25, and the score of the observance of patients’ rights in the operating room was 17.75 out of 36 with a standard deviation of 4.69 (11). Vahedian Azimi et al. showed that nurses’ awareness and observance of patients’ rights was excellent in more than 50% of cases (12).

The principle of observing the Patient’s Bill of Rights in any society is one of the most important ethical duties in the field of medical ethics, which has a long history in the medical world (13). The observance of patients’ rights improves the quality of patient care and increases patient satisfaction (14). Noncompliance with patients’ rights and their dissatisfaction with the services slow the recovery and increase hospitalization days, irritability, and treatment costs (15).

The observance of patients’ rights is not solely dependent on the personal wishes and tastes of care providers or instructions and directives; in this regard, monitoring systems must monitor the compliance with each part of these rights on an ongoing basis. Previous studies have suggested that to identify and eliminate the shortcomings in the observance of patients’ rights, the compliance with the content of the Patient’s Bill of Rights by the staff must be constantly monitored (16).

Operating and recovery rooms are among the medical wards of the hospital with the highest level of risk in terms of organizational, educational, environmental, and technological needs (17). Patients in the operating room have special rights because of their anesthesia, unfamiliarity with the treatment procedure, and fear of the unknown, and death. Given the unequal distribution of power and due to the patients’ need for staff in the operating room, the patients cannot express their discomfort. Besides, due to patients’ unawareness of their rights, patients’ anesthesia, and unawareness of all treatment processes, defending patients’ rights is one of the professional duties of operating room nurses (18). For example, Pishgar et al. reported that 56% of staff had a good awareness of patient rights, while compliance with these rights was reported to be satisfactory only in 15% of staff (17). Moreover, Hanani et al. showed that 19.6%, 39.2%, and 41.3% of technologists had a low, moderate, and good awareness of patient rights, respectively (19). In another study, Zandiyeh et al. reported that the observance of patients’ rights was at a moderate level in the operating rooms of teaching hospitals in Hamadan in 2012. They also suggested that patients need to become familiar with members of the treatment group, such as nurses, operating room technicians, and anesthesiologists, besides highlighting the importance of patient privacy and the provision of essential information about surgical and anesthesia procedures (16).

A review of the literature shows that most of the studies conducted in hospital wards have used self-report tools to collect data, and few studies have used checklists to check the observance of patients’ rights by members of the treatment team. Moreover, very limited studies have addressed the extent to which patients’ rights are observed by physicians. On the other hand, checklists are used as a useful tool to improve care methods and reduce morbidity and mortality rates. They are used even as a practical and effective tool for information exchange and team cohesion (20).

2. Objectives

Given the restrictions associated with questionnaires as self-report tools and the feasibility of using checklists to assess the performance of medical staff, the present study aimed to examine the observance of patients’ rights by operating room staff (physicians and technicians) using a checklist.

3. Methods

This descriptive-analytical cross-sectional study was conducted in 2018 on 142 technicians (including operating room technicians and anesthetists with an associate’s degree or above) and physicians specializing in surgery and anesthesia (including professors and senior medical students) working in the operating rooms of hospitals affiliated with Ahvaz University of Medical Sciences. The inclusion criterion was having at least 1 year of clinical work experience in the operating room, and the exclusion criterion was refusal to participate in the study.

Taking the type I probability error level of 5% and the type II probability error level of 2%,

Two participants who were not willing to cooperate were excluded from the study. The participants in 3 hospitals were selected using partially stratified random sampling. To this end, the operating room technicians, anesthetists, and physicians in each hospital were selected in proportion to the total number of technicians and physicians (n = 420) who met the inclusion criteria. Then, the names of all technicians and physicians from each hospital were written on pieces of paper and put in a container, and those whose names were taken randomly out of the container were selected as participants. A total of 98 operating room technicians and anesthetists and 46 physicians were selected as participants. However, since 1 technician and 1 physician left the study, the final sample included 97 technicians and 45 physicians.

The data were collected using a demographic information questionnaire and a researcher-made patient rights observation checklist to assess the observation of patients’ rights in the operating room by physicians and technicians. The checklist was developed based on the Patient’s Bill of Rights and Codes of Ethics for Iranian Nurses and assessed 5 areas of receiving optimal health services, protecting patient privacy and respecting the principle of confidentiality, the right to receive desirable and sufficient information, the right to choose freely to receive services, and the right to access an efficient grievance redressal system. The checklist items were responded with either “yes” or “no.” Items with a “yes” response were scored 1, and those with a “no” response were scored 0. A higher score indicated a higher degree of the observance of patients’ rights by the health care staff. The checklist used for anesthetists and operating room technicians consisted of 26 items with minimum and maximum scores of 0 and 26, respectively. The checklist used for anesthesiologists and surgeons contained 10 items with minimum and maximum scores of 0 and 10, respectively. After calculating the scores for each group of respondents, all scores were expressed as a percentage. A score of less than 50% indicated the poor observance of patients’ rights, a score between 51% and 75% indicated the moderate observance of patients’ rights, and a score of greater than 75% indicated the good observance of patients’ rights.

The validity of the patients’ rights observation checklist was assessed using content validity and a survey of 10 medical ethicists and technicians. The Content Validity Index (CVI) value for the checklist was 0.81. The reliability of the checklist was also verified using the Guttman test in a pilot study, in which the checklist was administered to 10 physicians and 20 technicians separately. The Guttman’s reliability coefficients for the technicians and physicians were 0.79 and 0.71, respectively. Furthermore, to check the reliability of the checklist and the agreement between the 3 raters, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was estimated as 0.971, indicating a very good inter-rater agreement.

After confirming the validity and reliability of the checklist and obtaining the code of ethics (code: IR.TUMS.FNM.REC.1395.994) from the ethics committee, the researcher referred to the operating rooms of the hospitals in the morning and evening shifts and selected those staff who met the inclusion criteria and signed the informed consent form. The selected participants were informed that their behavior would be observed during patient care, but to prevent the effect of recording observations on the observed behavior, an operating room staff member was selected in each hospital as an observer (3 observers in total) to collect the data. Moreover, the participants were not informed of the exact time of data collection. Finally, 142 persons were observed. The collected data were analyzed using SPSS version 20 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill, USA). The relative and absolute frequency, mean, SD, and independent samples t-test were used to describe the data.

4. Results

The mean age of the physicians in this study was 35.2 ± 7.6, with a range of 26 - 55 years. Moreover, the mean age of the technicians was 30.4 ± 6.3, with a range of 20 - 45 years. The data also showed that 72% of the anesthetists and 72.2% of the operating room technicians had a bachelor’s degree, implying that the 2 groups were homogeneous in terms of education. The majority of the physicians were final year students, including 75% of the anesthesiologists and 75.7% of the surgeons. Thus, no significant difference was observed in these 2 groups. In addition, 69.1% of the technicians were female, and 57.8% of the physicians were male. Moreover, 39.2% of the technicians and almost an equal number of physicians (39.3%) attended a workshop on professional ethics. However, 95.6% of the physicians participated in the workshop compared with only 38.1% of the technicians. Most of the physicians (86.7%) and technicians (67%) worked morning shifts. Furthermore, the majority of participants in the 2 groups were married (62.2% of the physicians and 58.8% of the technicians). Both groups of the operating room technicians and anesthetists were homogeneous in terms of background variables. The 2 groups of physicians were also homogeneous in terms of the background variables (Table 1).

| Variables | Anesthetists | Operating Room Technicians | Chi-Square | Anesthesiologists | Surgeons | Chi-Square |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | ||||

| Male | 5 (20) | 15 (20.8) | 7 (58.3) | 19 (57.5) | ||

| Female | 20 (80) | 57 (79.2) | 5 (41.7) | 14 (42.5) | ||

| Total | 25 (100) | 72 (100) | 12 (100) | 33 (100) | ||

| Attending workshops on professional ethics | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | ||||

| Yes | 10 (40) | 28 (39) | 5 (41.6) | 13 (39.4) | ||

| No | 15 (60) | 44 (61) | 7 (58.4) | 20 (60.9) | ||

| Total | 25 (100) | 72 (100) | 12 (100) | 33 (100) | ||

| Attending workshops on patient rights | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | ||||

| Yes | 10 (40) | 29 (40.2) | 11 (91.6) | 30 (90.9) | ||

| No | 15 (60) | 43 (59.8) | 1 (8.4) | 3 (9.1) | ||

| Total | 25 (100) | 72 (100) | 12 (100) | 33 (100) | ||

| Working shifts | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | ||||

| Morning | 16 (64) | 46 (63.8) | 7 (58.3) | 19 (57.7) | ||

| Evening | 2 (8) | 6 (8.3) | 1 (8.4) | 3 (9) | ||

| Morning-evening | 7 (28) | 19 (27.9) | 4 (33.3) | 11 (33.3) | ||

| Total | 25 (100) | 72 (100) | 12 (100) | 33 (100) | ||

| Marital status | P > 0.05 | P > 0.05 | ||||

| Single | 9 (36) | 26 (36.1) | 5 (41.6) | 14 (42.5) | ||

| Married | 16 (64) | 42 (63.9) | 7 (58.4) | 19 (57.5) | ||

| Total | 25 (100) | 72 (100) | 12 (100) | 33 (100) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

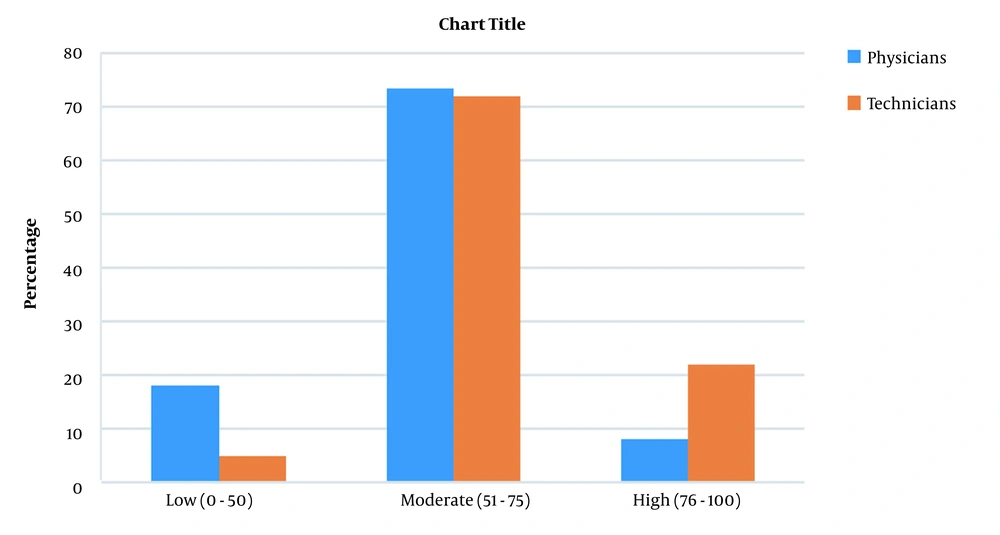

The mean score for the observance of patients’ rights by the technicians was 69.71 ± 10.5, indicating that patients’ rights were moderately observed by the technicians. Furthermore, the corresponding value for the physicians was 57.17 ± 11.7, indicating that patients’ rights were also moderately observed by the physicians (Figure 1). A comparison of the degree to which patients’ rights were observed by the 2 groups of technicians using the independent samples t-test indicated that the degree of the observance of patients’ rights between the 2 groups of anesthetists and operating room technicians was significantly different, and the observance of patients’ rights was higher among the anesthetists (P = 0.001). Furthermore, the anesthesiologists observed patients’ rights significantly more than the surgeons (P = 0.005; Table 2).

| The Observance of Patients’ Rights | No. | Min | Max | Mean ± SD | t-test Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technicians | t = 8.1; df = 95; P = 0.001 | ||||

| Anesthetists | 17 | 65.38 | 92.31 | 84.16 ± 7.31 | |

| Operating room technicians | 80 | 50 | 88.46 | 66.63 ± 8.23 | |

| Total | 97 | 50 | 92.31 | 69.7 ± 10.5 | |

| Physicians | t = 2.99; df = 43; P = 0.005 | ||||

| Anesthesiologists | 12 | 54.55 | 90.91 | 65.15 ± 9.36 | |

| Surgeons | 33 | 27.27 | 72.73 | 54.27 ± 11.24 | |

| Total | 45 | 27.27 | 90.91 | 57.17 ± 11.7 |

5. Discussion

This study examined the observance of patients’ rights in the operating room by physicians and technicians. The results confirmed the moderate observance of patients’ rights by anesthetists and operating room technicians. Since the adoption of the Patient’s Bill of Rights, various studies have addressed the degree of the observance of patients’ rights; however, most of them have addressed the issue by surveying patients using questionnaires. Zandiyeh et al. reported that the observance of patients’ rights by anesthetists and operating room staff was about 50%, while in the present study, it was about 70%. This difference can be attributed to the passage of time and the increasing importance of respect for patients’ rights by the medical staff (16). Moreover, Parniyan et al. conducted a study using a self-reported questionnaire (with a maximum score of 36) and showed that the average level of the observance of patients’ rights was 49.3% from the perspective of Jahrom operating room staff and 66.9% from the patients’ point of view (11). Accordingly, it can be argued that because patients in the operating room are often unconscious or in the recovery phase and do not have a high level of consciousness, their statements cannot be reliable. In line with the findings of the present study, Mohammadi and Rahimi Froshani assessed the observance of patients’ rights in hospitals affiliated with the Tehran University of Medical Sciences and found that the level of the observance of patients’ rights was moderate by the medical staff in these hospitals (22). Furthermore, Mahdiyoun et al. examined the relationship between nurses’ moral sensitivity and their respect for patients’ rights in intensive care units (ICUs) using a self-reported questionnaire. They reported that the level of the observance of patients’ rights in ICUs by nurses was higher than average (23). Nekoei Moghaddam et al. examined the awareness and observance of patients’ rights from the perspective of patients and nurses in surgical centers in Kerman and showed that 67.3% of nurses and 66.9% of patients considered that the observance of patients’ rights was favorable (24). However, some studies have reported very low levels of the observance of patients’ rights. For instance, Kazemnezhad and Hesamzadeh reported a poor or moderate level of compliance with the Patient’s Bill of Rights from the perspective of more than two-thirds of medical and nursing staff in different wards of 4 teaching hospitals of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences in Sari (21). Furthermore, Ghanem et al. examined the observance of patients’ rights from the perspective of physicians and nurses and reported a low level of the observance of patients’ rights, possibly due to the lack of awareness, insight, supervision, and similar issues (25). Younis et al. also examined the observance of patients’ rights in Sudan and highlighted the need for improving the observance of patients’ rights by medical staff (26).

Most studies have reported that the observance of patients’ rights by operating room technicians is moderate and higher, which can be due to the holding of regular training classes in hospitals and the implementation of clinical governance policies in Iranian hospitals (9).

The data in the present study confirmed the moderate observance of patients’ rights by physicians. Sharifi and Mafi reported that the observance of patients’ rights was desirable in 41.6% of the cases in the inpatient wards of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in Tehran (3). The participants in this study were medical students completing their internship courses in different wards of the hospital, and the data were collected through a questionnaire. In another study, Haji Babai et al. examined the relationship between awareness and observance of patients’ rights by assistants and psychiatrists in Ahvaz. They showed that they were well aware of patients’ rights, and 55% of psychiatrists reported a desirable level of the observance of patients’ rights (27). Furthermore, Basiri Moghadam found that despite the knowledge of medical staff about patients’ rights, the compliance with the Patient’s Bill of Rights was not at the desired level, and factors other than awareness affected the compliance with the Patient’s Bill of Rights that need to be taken into account (28).

In line with the present study, Abedi et al. conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of awareness and observance of patients’ rights. They found that the observance of patients’ rights was somewhat satisfactory. They also highlighted the need for measures such as a better description of the Patient’s Bill of Rights and increasing patients’ awareness of their rights (29). They reviewed studies addressing the observance of patients’ rights from the perspective of patients. Thus, patients’ unawareness of their rights could have affected the results of the study. However, in the present study, the observance of patients’ rights was examined by a researcher using a checklist. Furthermore, Sookhak et al. assessed nurses’ awareness and observance of patients’ rights using a cross-sectional descriptive method. The results showed nurses’ low awareness of patients’ rights and the moderate observance of these rights. Thus, they highlighted the need for improving nurses’ awareness and the observance of patients’ rights through in-service training programs (30). Sookhak et al. only surveyed nurses. In contrast, the present study assessed only operating room technicians and physicians. Similar to the data in the present study, Kazemnezhad and Hesamzadeh reported a low level of the observance of patients’ rights by physicians in the whole hospital (21). However, the present study only examined the level of the observance of patients’ rights in the operating room by technicians and physicians.

5.1. Conclusions

The results of the present study confirmed the moderate observance of patients’ rights in the operating room by operating room staff and physicians. Since the observance of patients’ rights leads to the improvement of the quality of care and trust in the medical centers, special measures need to be taken to improve the observance of patients’ rights in clinical settings as much as possible. Thus, it seems necessary to hold refresher courses in medical ethics and patients’ rights for health care and medical staff. Furthermore, more attention should be paid to informing patients about their rights. This helps patients become more aware of this important issue and ask the health care staff to observe it.

5.2. Limitations

One of the limitations of this study is that the participants were selected at a specific time and place, limiting the generalizability of the findings to the entire patient population.