1. Background

Pain is a process of daily burn dressing changes (1). Evidence has shown that burn pain cannot be completely controlled with painkillers (2). Therefore, pain control is considered a primary issue in burn care (3).

Non-pharmacological methods are superior to pharmacological methods due to building confidence, participation of help-seekers, having no side effects, and being pleasant for the patient (4). One of the non-pharmacological measures that play a vital role in preventing and relieving patients’ pain is religious beliefs (5-7). Evidence has shown that the spiritual dimension is critical in caring for and relieving patients’ pain, and medical staff must know the religious aspects of the people of their region to help them with palliative care (8, 9).

One of the religious actions performed individually and in-group that play an essential role in pain relief due to various diseases is prayer and praise (10, 11). As an important type of prayer, the name of Allah plays a role in a human’s closeness to God and flourishing latent human talents. From the Islamic perspective, remembering God’s name calms the heart, heals the heart and pain, polishes the heart, and heals the mind (12). In the Qur’an, God introduces dhikr and his name as greater than anything imaginable for human thought and mind and considers it to be equal to pray, showing the importance of dhikr among other worships (13). Many psychologists and psychiatrists today have found that dhikr and complete attention to God with all organs and senses cause one to turn away from life’s problems and mental occupations, thereby leading to relieving anxiety, concern, and phobia and helping mental relaxation (14). Numerous studies have also indicated the successful effect of dhikr and remembering God’s names on relieving the pain caused by invasive procedures (12, 15-17). The study by Avazeh et al. showed that in patients with burns, the dhikr of “Allah” could effectively decrease pain and anxiety stemming from dressing changes (15).

Assessing and managing pain are essential components of nursing practice. We conducted the current study considering the results of Wiechman Askay and Magyar-Russell’s study indicating the effectiveness of religious beliefs in the recovery of burn patients (18), given the importance of pain relief in burn patients and knowing that common pain relieving methods are costly and have side effects. We found only one similar study on burn patients (15).

2. Objectives

In this trial, we evaluated patients’ religious beliefs and investigated the effect of the praises of Hazrat Fatima (PBUH), one of the well-known and familiar dhikrs in Islam, on pain severity and quality of burn dressing change.

3. Methods

This randomized clinical trial was conducted in 2017 in a ward of Nekouei-Hedayati Hospital, Qom University of Medical Sciences. The sample size included 80 eligible patients admitted to the burn ward who entered the study by simple random allocation. According to the mean and standard deviation of pain severity due to dressing change in patients with burns in Avazeh et al.’s study (15) (7.85 ± 4.1 in the control group and 5.21 ± 3.2 in the experimental group) and considering the formula for comparing the means, α = 0.05, and β = 0.1, the sample size was calculated as 40 individuals in each group.

Inclusion criteria were willingness to participate in the study, having Islam religion (Shia), believing in Islamic dhikr, having a minimum level of literacy and the ability to speak and communicate, having passed the emergency stage, entering the acute stage of burn (that starts from 48 - 72 hours after the burn onset), having a second or third-degree burn, having a burn rate of 20 - 50%, the patient’s wound freshness, and the patient’s alertness and his need for povidone-iodine bandages. Exclusion criteria included the patient’s unwillingness to continue the study.

After obtaining the approval of the Ethics Committee of Qom University of Medical Sciences and the code of the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT20140428017468N5), sampling was done under the ethical considerations of the Helsinki Declaration (19). First, the questionnaire of demographic and clinical characteristics (age, sex, place of residence, marital status, body mass index, belief in Islamic dhikr, ethnicity, length of stay, cause, and agent of burns, burn site, burn percentage, and substance-related disorders) was completed for each patient by a research colleague. Then, participants were selected by convenience sampling and assigned to experimental and control groups using stratified random sampling. First, classes were created for each combination of burn degree (including two classes: First-degree burn and second-degree burn), percentage (including two classes: Two numerical intervals), and agent (including three classes: Thermal, electrical, and chemical). Then, the patients were assigned to the appropriate class of the variables, and a simple random method (lottery) was performed in each category to assign patients to one of the groups.

Patients in both groups received analgesics and sedatives on demand, and their type, dosage, time, and frequency were recorded. Then, 10 minutes before the dressing change in the dressing room, patients were asked to recite the praises of Hazrat Fatima (PBUH), which included repeating God’s name 100 times (34 times “Allah Akbar,” 33 times “Alhamdulillah,” and 33 times “Sobhan Allah”). The control group received only routine care. Patients’ pain severity was measured before and 15, 30, 45, and 60 minutes after the dressing change in both groups. A research colleague administered the modified McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) 15 minutes after starting the dressing change to assess pain quality during the dressing change. In the present study, research unit randomization, data entry, and data analysis were performed by research colleagues.

The Visual Analog Scale for pain consists of a 10-cm-long vertical or horizontal line numbered from zero to 10 (a score of zero indicates a lack of pain, and a score of 10 shows the maximum pain the patient could imagine). The validity of the Visual Analog Scale for pain has been confirmed in several studies (20, 21). The reliability of this scale has also been confirmed using the retest method in Gallagher et al.’s study, with r = 0.99 (20).

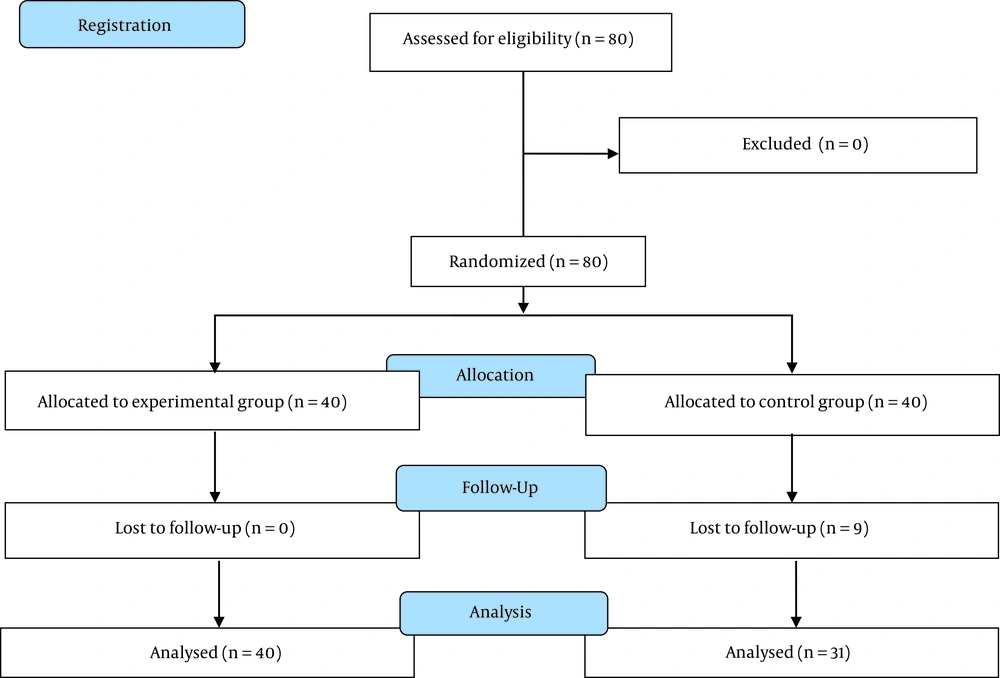

The modified MPQ consists of 12 words to assess pain quality in sensory (nine words) and emotional (three words) dimensions of pain. The response to each word is classified as “at all,” “mild,” “moderate,” and “severe,” and the scores assigned to these answers are “0”, “1”, “2”, and “3”, respectively. A total score of “0” indicates the minimum total score, and a score of “36” indicates the maximum total score. This questionnaire was completed after the dressing change by asking the patient by a research colleague. The patient was asked to report pain quality during the burn dressing change by choosing the appropriate words after the dressing change. For content validity, this questionnaire was first translated and edited by a linguist and then reviewed and approved by Mazlom et al. by five faculty members of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (22). After collecting and coding, the data were entered into the computer. After ensuring the accuracy of data entry, the normal distribution of quantitative data was assessed by the Shapiro test. Descriptive statistics and statistical tests (such as independent t-test, analysis of variance (ANOVA), repeated-measures analysis, chi-square, and Fisher exact test) were used to analyze the data using SPSS software version 22. A 95% confidence interval (α = 5%) was considered for the performed tests. The collected data from nine patients in the study were incomplete. Therefore, statistical analysis was done on the remaining 71 patients (Figure 1).

4. Results

The mean age of patients in the experimental group and control group was in the range of 40 - 50 years. In the present study, 85.0% (n = 34) of the experimental group were male, and 15.0% (n = 6) were female. Also, 80.6% (n = 25) of the patients in the control group were male, and 19.4% (n = 6) were female. In the experimental group, the burn agent was thermal in 77.5% (n = 31) of the patients, electrical in 20% (n = 8), and chemical in other patients. In the control group, the burn agent was thermal in 77.5% (n = 24) of the patients, electrical in 16.1% (n = 5), and chemical in other patients. There was a third-degree burn in 92.5% (n = 37) of the experimental group and 79.4% (n = 24) of the control group. Patients in both groups were homogeneous regarding burn agent, degree, and percentage, as well as sex and age (P > 0.05) (Table 1). Regarding receiving analgesics, all study participants received analgesics (morphine 5 mg once only). For 15% (n = 6) of the experimental group and 16.1% (n = 5) of the control group, a constant amount of 1 mg of midazolam was used only once for sedation. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding receiving sedatives (P = 0.896).

| Variables | Groups | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | ||

| Gender | 0.627 b | ||

| Male | 34 (85.0) | 25 (80.6) | |

| Female | 6 (15.0) | 6 (19.4) | |

| Burn agent | 0.690 c | ||

| Thermal | 32 (79.5) | 24 (77.5) | |

| Electrical | 8 (20.5) | 5 (17.1) | |

| Chemical | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.4) | |

| Burn degree | 0.06 b | ||

| Second-grade | 3 (7.5) | 7 (22.6) | |

| Third-degree | 37 (92.5) | 24 (79.2) | |

| Burn percentage | 31.3 ± 9.8 | 29.8 ± 9 | 0.971 d |

| Age | 42.74 ± 11.4 | 46.02 ± 9.3 | 0.134 d |

Burn Patients’ Characteristics in Experimental and Control Groups a

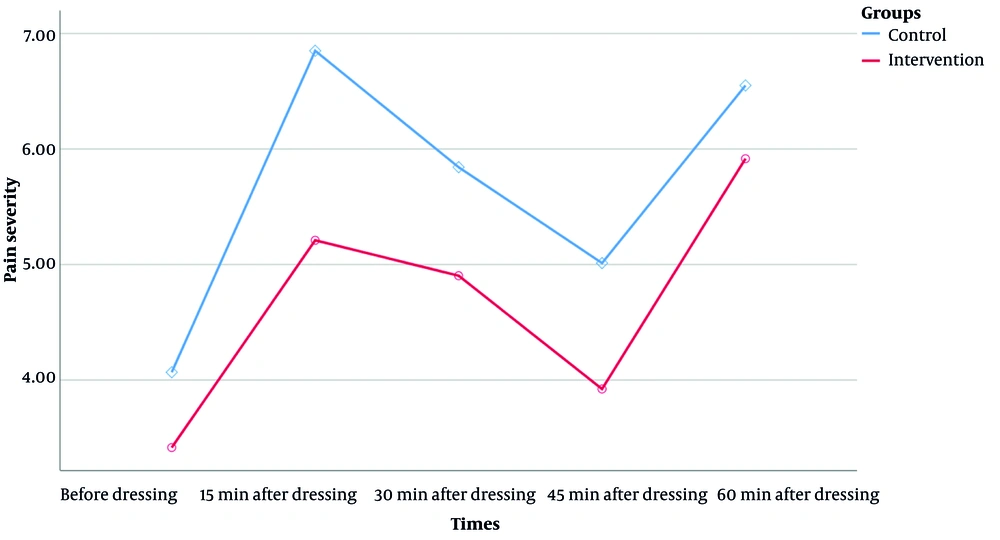

The independent t-test showed no statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups before the dressing change (P > 0.05). However, this test showed a statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of mean pain severity of dressing change 15, 30, and 45 minutes after the dressing change (P < 0.05; Table 2). Based on the repeated-measures analysis, the mean pain severity scores changed statistically significantly across all phases of the study (F = 30.42, P < 0.001; Figure 2). Mauchly’s sphericity test was significant, so we used Greenhouse-Geisser analysis to examine the effects of time, group, and time-group interaction, showing that all these effects were significant (Table 2).

| Pain Severity | Groups | Significance Level | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | ||

| Before | 3.41 ± 1.45 | 4.06 ± 1.69 | 0.092 b |

| 15 min after | 5.20 ± 1.50 | 6.85 ± 2.13 | 0.001 b |

| 30 min after | 4.90 ± 1.83 | 5.84 ± 1.90 | 0.04 b |

| 45 min after | 3.92 ± 1.42 | 5.01 ± 1.76 | 0.007 b |

| 60 min after | 5.91 ± 2.04 | 6.55 ± 1.94 | 0.187 b |

| Effect | |||

| Time | < 0.001 c | ||

| Time-group | 0.008 c | ||

| Group | 0.002 c | ||

The Mean Pain Severity Score Over Five Measurements a

The independent t-test showed a statistically significant difference in the scores of sensory and emotional dimensions and the total score of pain quality between the experimental and control groups (P = 0.007, P = 0.047, and P = 0.003, respectively) (Table 3).

The Mean Scores of Sensory and Emotional Dimensions and the Total Score of Pain Quality of Burn Patients During Burn Dressing Change in the Experimental and Control Groups a

Fisher’s exact test did not show any statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups in the frequency of words of pain severity. However, this test showed a statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups in the pattern during dressing change (Table 4).

| Variables | Groups | Significance Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | Total | ||

| Pain severity during dressing change | 0.615 b | |||

| Painless | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Mild | 8 (20) | 5 (16.1) | 13 (18.3) | |

| Annoying | 12 (30) | 12 (38.7) | 24 (33.8) | |

| Torturous | 9 (22.5) | 8 (25.8) | 17 (23.9) | |

| Terrible | 11 (27.5) | 5 (16.1) | 16 (22.5) | |

| Gethsemane | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Total | 40 (100) | 31 (100) | 71 (100) | |

| Pain pattern | 0.001 b | |||

| Painless | 2 (5.0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.8) | |

| Short | 5 (12.5) | 3 (9.7) | 8 (11.3) | |

| Periodic | 15 (37.5) | 25 (80.6) | 40 (56.3) | |

| Ongoing | 18 (45.0) | 3 (9.7) | 21 (29.6) | |

| Total | 40 (100) | 31 (100) | 71 (100) | |

The Frequency Distribution of Burn Patients in Terms of Pain Severity and Pain Pattern During Burn Dressing Change in Experimental and Control Groups a

5. Discussion

The present study indicated the effect of reciting the praises of Hazrat Fatima (PBUH) on pain severity stemming from patients’ burn dressing changes. According to the results of this study, 15, 30, and 45 minutes after the dressing change, the pain severity was significantly lower in the group that recited the praises of Hazrat Fatima (PBUH) than in the experimental group. Also, reciting the praises of Hazrat Fatima (PBUH) could affect the pain quality stemming from burn dressing change in both sensory and emotional dimensions.

The results of Hoven’s study showed that remembering God’s name could lead to the stabilization of vital signs and, finally, patients’ pain relief (23). Remembering God’s name leads to reduced breath rate and brain wave activities. Similar to medicine, prayer can affect diseases (12).

The results of Avazeh et al.’s study showed that remembering God’s name could affect burn pain, which is consistent with the results of the present study (15). In 2018, Farzin Ara et al. conducted an experimental study to compare the effect of the dhikr of “Allah” to the effect of rhythmic breathing on pain after orthopedic surgery in Mashhad. This study showed that both methods could lead to stimulating higher brain centers, closing gates (gate control theory of pain), and preventing more pain in the patient (24). In 2013, Nasiri et al. did a study investigating the effect of remembering God’s name on pain severity after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Researchers of this study concluded that remembering God’s name was effective in pain relief in patients after coronary artery bypass graft surgery (17).

Therefore, it is recommended that more attention be paid to the religious beliefs of patients with burns in their care programs, and remembering God’s name be used in managing pain at burn dressing change and the resultant anxiety. It is also suggested that future studies investigate the effect of other Islamic dhikrs, such as “LahoawlowalaghovataEllabellahelal-Ali al-'Azim,” on the pain and anxiety stemming from the pain during burn dressing change.

5.1. Limitations

In this study, the possibility of different pain thresholds and individual differences between patients should be mentioned as a limitation. Another limitation of the present study is the Shiite religion of the patients participating in the study, so the research results can only be generalized to this population.

5.2. Conclusions

The present study indicates the favorable effects of reciting the praises of Hazrat Fatima (PBUH) on pain severity and quality stemming from burn dressing change. Therefore, this dhikr can be recommended as a complementary therapy for analgesics.