1. Background

Substance dependence is characterized by a maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as indicated by one (or more) of the following symptoms occurring within a 12-month period (such as time of use, craving, inability to work, seeking substances, neglecting important activities, using substances in risky situations, using substances despite known risks, developing tolerance, and experiencing withdrawal symptoms that alleviate with further substance use) (1). According to Iran’s Drug Control Headquarters (DCHQ), the prevalence of drug use in Iran is reported to be 5.4% among individuals aged 15 to 64 (2), although some studies have reported even higher rates, up to 11.9% (3). Addiction is a complex phenomenon that impacts various aspects of an individual's life, including biological, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions (4, 5). Additionally, addiction often coexists with chronic pain (6), with substance use associated with increased pain symptoms (opioids: P < 0.026; OR = 1.52) (7). Approximately 27% to 87% of individuals with substance use disorder (SUD) also experience chronic pain, and they are 1.5 times more likely to have chronic pain, while those with chronic pain are 2 to 3 times more likely to develop SUD (8).

Chronic pain is defined as pain that persists or recurs for more than three months and results in daily functional impairment (9). Untreated chronic pain can become more complex pathophysiologically than pain arising from the initial condition, potentially leading to structural and functional changes in the nervous system. Consequently, pain transitions from being a symptom of the primary condition to becoming a distinct disorder (10). Chronic pain can have both physical and psychological repercussions for patients, as well as significant healthcare and economic burdens and diminished productivity (11). Patients with chronic pain often face an increased risk of developing complications, including alterations in cognitive processes such as memory and attention (12), changes in brain chemistry and neocortical gray matter (13), and challenges in accurately perceiving chronic pain and related behavioral aspects (14) Chronic pain is linked to elevated rates of major depressive disorder in American adults (15), suicidal ideation and attempts (16), sleep disturbances (17), sexual dysfunction (18), and conditions like hypertension (19). Despite these challenges, maintaining functional abilities despite chronic pain is a key goal of various treatment interventions. Moreover, not all individuals with chronic pain become disabled; some are able to continue fulfilling their responsibilities and engaging in activities despite experiencing pain (20).

Failure to manage pain can result in health and social challenges, including mental health issues and substance misuse (21). Chronic pain, coupled with diminished positive emotional responses to natural rewards, may exacerbate restlessness, reinforcing cravings for opioids and the likelihood of relapse (7). Therefore, behavioral therapies aimed at alleviating chronic pain and enhancing positive affect may complement pharmacological treatments effectively (22). Generally, adherence to and desire for treatment can be considered as evaluations of drug abusers' readiness to change (23). Researchers have yet to identify a single key variable that determines treatment adherence (24). Studies have validated the influence of various factors on non-adherence, such as demographic factors, incentives, attitudes, and psychological variables (e.g., denial, depression, dementia, cultural considerations, and substance abuse), as well as the significance of social support in treatment adherence (25). Investigations into behavioral interventions related to substance abuse, smoking cessation, and chronic pain have reported comparable relapse rates post-treatment (26). These findings underscore the continual need to understand the factors affecting treatment, adherence, and recurrence in individuals with chronic pain, affirming the importance of cognitive behavioral interventions (27). Researchers have noted that Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT)-based interventions, categorized as third-wave therapies, effectively reduce consumption and craving levels in patients, contributing to improved psychological symptoms and reduced relapse rates in substance dependence (28, 29).

2. Objectives

This study aimed to address chronic pain and other factors influencing dependence and treatment adherence by employing a combination of three approaches: (1) Acceptance and commitment therapy, which focuses on enhancing psychological flexibility through awareness, acceptance, and behavior change strategies (30); (2) dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), rooted in behaviorism and dialectical philosophy to regulate emotions and bolster distress tolerance (31); and (3) exercise for chronic pain management, aiming for optimal oxygen absorption (32). The effectiveness of these interventions was compared in terms of enhancing health-related quality of life, improving physical fitness, alleviating symptoms of depression and anxiety, and managing psychiatric conditions (33, 34).

3. Methods

This quasi-experimental study employed a pre-test-post-test design with a two-month follow-up, including a control group. Following Stevens , the sample size was estimated at 15 individuals per group, totaling 75 participants across five groups, considering a minimum test power of 75%, an error probability of 0.05, and an average effect size of 0.50 (35). The participants, all male, were selected via convenience sampling from patients undergoing addiction treatment at Taban, Hayate Pak, and Omid addiction treatment centers in Zahedan between April 20, 2021, and June 19, 2021. They were then randomly assigned to the ACT with exercise, ACT without exercise, DBT with exercise, DBT without exercise, and control groups. Inclusion criteria comprised confirmation of chronic pain by a physician, absence of chronic pain due to clear issues such as infection or bone fracture, absence of serious psychiatric disorders, no concurrent participation in other psychotherapy interventions or narcotics anonymous (NA) meetings, no use of psychoactive drugs during the study period, and literacy in reading and writing to respond to questionnaires. Exclusion criteria included patient unwillingness to continue treatment, missing more than two sessions or discontinuing addiction treatment, and experiencing physical issues during interventions requiring hospitalization.

After obtaining permission from the Zahedan Welfare Department, the researcher visited addiction treatment centers to provide information about the study objectives. Based on the inclusion criteria, a total of 75 patients (30 from Hayate Dobare Center, 30 from Taban Center, and 15 from Omid Center) completed the questionnaire items (36). Participants in all intervention groups attended eight sessions, one per week, while those in the ACT with exercise and DBT with exercise groups also participated in 24 one-hour aerobic exercise sessions, three times per week. Conversely, the control group did not receive any therapy or exercise interventions.

3.1. Instruments

Data collection in this study utilized a demographic information form (including age, education, marital status, and occupation), the Pain Outcomes questionnaire-VA (POQ-VA), and the Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness scale (SOCRATES).

Pain Outcomes questionnaire-VA (POQ-VA): This concise 20-item tool was developed by Clark, Gironda, and Clark et al. It employs a 10-point Likert scale to assess various aspects of pain outcomes, such as pain intensity, mobility, activities of daily living, vitality, negative affect, and fear of pain. The total score is derived by summing up individual item scores. A factor analysis study demonstrated significant correlations (P < 0.01), accounting for 72% of total variance. The coefficients of the entire questionnaire were deemed acceptable, exceeding 0.75 (37). Haghighat confirmed its construct validity through factor analysis and verified its reliability with an internal consistency of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.80 (38). Navidzade also affirmed its reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92 (39). In our study, the scale's reliability was confirmed with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.90.

Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness scale (SOCRATES): Developed by Miller and Tonigan (1996), this scale assesses the readiness of substance abusers to change. It comprises 19 items gauging treatment desire on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5), categorized into three subscales: Ambivalence about change, recognition of substance-related problems, and taking steps. The scale's construct validity and internal consistency were reported as 0.78 and 0.89, respectively. Additionally, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.89 confirmed its internal consistency and psychometric properties (23). Monfared et al. demonstrated the effectiveness of a treatment desire model based on addiction memory and desire to use mediated by self-control for individuals seeking to overcome drug dependence (40). In our study, the instrument's reliability was affirmed with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89.

Following completion of pre-test questionnaires, ACT-based interventions were implemented according to the protocol devised by Dahl et al. for adults with chronic pain. This protocol emphasizes acceptance, defusion, self as context, here and now, values, and committed action, as outlined in Table 1 (41).

| Session | Focus | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Pretest | Familiarizing with the group members, gaining the participants’ trust, filling out the questionnaires. |

| 1 | Pain response | Introducing the therapist and group members, establishing the therapeutic relationship, introducing ACT, its goals, and core processes, explaining the intervention rules and protocols, discussing chronic pain and its categories. |

| 2 | Creative helplessness and valuation | Inducing creative helplessness, discussing positive and negative reactions to pain, values and negative reactions to pain, summarizing the discussions, and assigning homework. |

| 3 | Objectifying values | Defining acceptance and failure, despair, denial, resistance, challenges, and problems rejected or accepted, actions that make a person close to or distant from values, and assigning homework. |

| 4 | Controlling the problem | Performing exercise, assignment, and behavioral commitment, conceptualized fusion and defusion, cognitive defusion techniques, intervening in problematic linguistic and metaphorical cycles, weakening self-alliance with thoughts and emotions. |

| 5 | Cognitive defusion and acceptance | How to accept some negative experiences in favor of valuable actions, focusing on one’s activities (e.g., breathing, walking, etc.), and being aware of oneself at the present moment |

| 6 | Encounter (in theory) | Using the ladder of painful situations by classifying such situations, using mindfulness techniques with a focus on the present moment, wrapping up the discussions, reviewing the assignment for the next session, and presenting homework |

| 7 | Encounter (in practice) | Specifying the most important values and goals fitting these values, behaviors done to fulfill the intended goals, determining risks, and focusing on outcomes |

| 8 | Summarizing and conclusion | Identifying behavioral schemas fitting values, creating commitment to the values, discussing relapse and how to cope with it, and reminding that sometimes we have to act against committed values. |

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Protocol for Treating Chronic Pain

Dialectical behavior therapy-based interventions for treating chronic pain followed Linton’s protocol (42), which was translated and standardized for use in Iran by Amini-Fasakhoudi et al. The protocol consisted of eight 90-minute sessions focusing on intervention goals, content, and exercises performed both in-session and outside (see Table 2) (42, 43).

| Session | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Welcoming and introducing group members, stating the intervention goals and rules, providing some information about the causes and factors aggravating the disease, and providing some instructions about the DBT intervention |

| 2 | Providing instructions on how to regulate emotions and take less painkillers and sedatives, tolerating distress such as returning attention, doing enjoyable activities, visualizing a safe place, and conscious breathing |

| 3 | Discussing basic mindfulness techniques such as focusing on one object in 1 minute, cognitive defusion in 5 minutes, and light control in 10 minutes, and doing daily tasks with mindfulness such as eating with mindfulness |

| 4 | Introducing mindfulness techniques such as observation of thoughts, pure acceptance with the help of developing a non-judgmental view, and the technique of filling emotion regulation sheets by identifying and recording emotions and the relationship between emotions, thoughts, and behavior. |

| 5 | Introducing encounter as a behavioral therapy technique for activities that the patient avoids due to fear, discussing the hierarchy of fear and avoidance, and designing emotional encounter exercises to replace effective responses. |

| 6 | Introducing behavior analysis techniques by identifying the antecedents and consequences reinforcing behavior and manipulating the factors that maintain ineffective behavior and then replacing them with efficient behavior. |

| 7 | A review of the introduced techniques (tolerating distress, mindfulness, and emotion regulation) |

| 8 | Encouraging the patient to continue the treatment program by doing homework to prevent relapse |

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), Interventions

Additionally, 24 group aerobic exercise sessions, each lasting one hour per week, were held from 9 - 10 a.m. at the addiction treatment camps for patients in the ACT and DBT groups with exercise. These exercise sessions were scheduled on days separate from the ACT and DBT intervention days. Following the interventions, post-tests were administered to participants in all groups. Furthermore, two months after completing the interventions, questionnaires were readministered to patients in all groups. Social workers in the treatment centers invited patients for questionnaire completion during the follow-up stage.

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS-26 software, employing repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni’s post-hoc test at a significance level below 0.05 (P < 0.05). Additionally, Box's M test was utilized to assess homogeneity of variance-covariance matrices. The Shapiro-Wilk test confirmed normal distribution of variables, as the estimated values for the variables exceeded 0.05, meeting the assumption of normal distribution of scores. To adhere to ethical protocols, the ACT intervention was offered to control group patients interested in the intervention program content, conducted two weeks after the follow-up phase.

4. Results

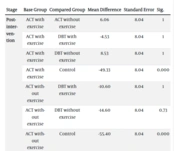

The findings indicated homogeneity among the control and intervention groups concerning demographic factors such as age, education, marital status, and occupation, with no statistically significant difference observed across the five groups (Table 3). Data from repeated measures ANOVA revealed significance for the intragroup effect (time) across three evaluation stages for both ACT and DBT interventions with and without exercise concerning the pain outcome variable (P = 0.01). Moreover, significant group-time interaction effects (P = 0.003) and group effects (P = 0.001) were noted. Significant group-time effects were also observed across the three evaluation stages (P = 0.004), along with significant intergroup differences (P = 0.001) (Table 4). Additionally, Bonferroni’s post-hoc test results demonstrated significant effectiveness of ACT and DBT interventions with and without exercise in controlling pain outcomes and enhancing the desire for treatment compared to the control group at the post-intervention stage. However, in the follow-up stage, only ACT interventions with and without exercise exhibited significant impacts on these variables compared to the control group (Table 5). Moreover, ACT intervention with exercise showed superior efficacy in controlling pain outcomes compared to other interventions (Table 6).

Regarding the desire for treatment, repeated measures ANOVA results across the three measurement occasions indicated significant intragroup effects (time) for ACT and DBT interventions with and without exercise (P = 0.004; P = 0.001). Significant group-time interactions were also noted for the desire for treatment (P = 0.001). Furthermore, analysis of the group effect across the three evaluation stages revealed significant intergroup differences in the desire for treatment for ACT and DBT interventions with and without exercise (P = 0.001; P = 0.01) (Table 7). Bonferroni’s post-hoc test showed that ACT and DBT interventions with and without exercise significantly impacted the research variables at the post-intervention stage (P = 0.001) compared to the control group. Similarly, in the follow-up stage, ACT interventions with and without exercise and DBT without exercise demonstrated significant effectiveness on the research variables compared to the control group (P = 0.001) (Table 8). Finally, ACT intervention with exercise proved significantly more effective in enhancing the desire for treatment compared to the control group (P = 0.01) and DBT intervention with exercise (P = 0.001). Similarly, ACT intervention without exercise was significantly more effective in improving the desire for treatment compared to DBT with exercise and the control group (P = 0.01; P = 0.001) (Table 9).

| Variables and Categories | No, (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT Intervention | DBT Intervention | Control Group | |||

| With Exercise | Without Exercise | With Exercise | Without Exercise | ||

| Age (y) | |||||

| 19 - 30 | 8 (53.3) | 9 (60) | 7 (46.7) | 9 (60) | 7 (46.7) |

| 31 - 42 | 5 (33.3) | 5 (33.3) | 6 (40) | 4 (26.7) | 6 (40) |

| 43 - 54 | 2 (13.3) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (13.3) | 2 (13.3) | 2 (13.3) |

| Education | |||||

| Illiterate | 2 (13.3) | 3 (20) | 2 (13.3) | 2 (13.3) | 2 (13.3) |

| Primary school | 4 (26.7) | 3(33.3) | 3(20) | 2 (13.3) | 5 (33.3) |

| Middle school | 8 (53.3) | 6 (40) | 5 (33.3) | 4 (26.7) | 7 (46.7) |

| Diploma and higher education | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.7) | 5 (33.4) | 7 (46.6) | 1 (6.7) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 7 (46.7) | 9 (60) | 8 (53.3) | 10 (66.7) | 8 (53.3) |

| Married | 8 (53.3) | 6 (40) | 7 (46.7) | 5 (33.3) | 7 (46.7) |

| Employment | |||||

| Unemployed | 4 (26.7) | 4 (26.7) | 3 (20) | 4 (26.7) | 4 (26.7) |

| Self-employed | 11 (73.3) | 11 (73.3) | 12 (80) | 11 (73.3) | 11 (73.3) |

Participants’ Demographic Data

| Groups | Variables | Index | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Squares | F | Sig. | Effect Size | Test Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT and DBT with exercise | Intragroup changes | Time | 1384.54 | 1 | 1384.54 | 6.78 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.72 |

| Group-time | 2744.02 | 2 | 1372.01 | 6.72 | 0.003 | 0.24 | 0.89 | ||

| Error | 8669.93 | 42 | 204.04 | ||||||

| Intergroup changes | Group | 49246.50 | 2 | 24623.25 | 12.05 | 0.001 | 0.39 | 0.99 | |

| Error | 58759.15 | 42 | 2041.88 | ||||||

| ACT and DBT without exercise | Intragroup changes | Time | 376.17 | 1 | 376.17 | 4.67 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.56 |

| Group-time | 1041.75 | 2 | 520.87 | 6.47 | 0.004 | 0.23 | 0.88 | ||

| Error | 3381.06 | 42 | 80.50 | ||||||

| Intergroup changes | Group | 58801.71 | 2 | 29404.35 | 13.01 | 0.001 | 0.38 | 0.99 | |

| Error | 94878.88 | 42 | 2259.02 |

ANOVA Results for Pain Outcomes in the Intervention Groups

| Stage | Base Group | Compared Group | Mean Difference | Standard Error | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-intervention | ACT with exercise | ACT without exercise | 6.06 | 8.04 | 1 |

| ACT with exercise | DBT with exercise | -4.53 | 8.04 | 1 | |

| ACT with exercise | DBT without exercise | 8.53 | 8.04 | 1 | |

| ACT with exercise | Control | -49.33 | 8.04 | 0.000 | |

| ACT without exercise | DBT with exercise | -10.60 | 8.04 | 1 | |

| ACT without exercise | DBT without exercise | -14.60 | 8.04 | 0.73 | |

| ACT without exercise | Control | -55.40 | 8.04 | 0.000 | |

| DBT with exercise | DBT without exercise | -4 | 8.04 | 1 | |

| DBT with exercise | Control | -44.80 | 8.04 | 0.000 | |

| DBT without exercise | Control | -40.80 | 8.04 | 0.000 | |

| Follow-up | ACT with exercise | ACT without exercise | 7.40 | 8.89 | 1 |

| ACT with exercise | DBT with exercise | -6.26 | 8.89 | 1 | |

| ACT with exercise | DBT without exercise | -9.66 | 8.89 | 1 | |

| ACT with exercise | Control | -51.26 | 8.89 | 0.000 | |

| ACT without exercise | DBT with exercise | -13.66 | 8.89 | 1 | |

| ACT without exercise | DBT without exercise | -17.06 | 8.89 | 0.59 | |

| ACT without exercise | Control | -58.66 | 8.89 | 0.000 | |

| DBT with exercise | DBT without exercise | 6.26 | 8.89 | 1 | |

| DBT without exercise | Control | -3.40 | 8.89 | 1 |

Bonferroni’s Post-hoc Test for Pain Outcomes in the Control and Intervention Groups

| Stage | Base Group | Compared Group | Mean Difference | Standard Error | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-intervention | ACT with exercise | DBT with exercise | 43.73 | 9.52 | 0.001 |

| ACT with exercise | Control | 41.73 | 9.52 | 0.001 | |

| DBT with exercise | Control | 39.17 | 9.52 | 0.001 | |

| Follow-up | ACT with exercise | DBT with exercise | 42.70 | 9.52 | 0.001 |

| ACT with exercise | Control | 41.73 | 9.52 | 0.001 | |

| DBT with exercise | Control | 39.17 | 9.52 | 0.001 | |

| Post-intervention | ACT without exercise | DBT without exercise | 35.17 | 10.02 | 0.001 |

| ACT without exercise | Control | 50.08 | 10.02 | 0.001 | |

| DBT without exercise | Control | -33.91 | 10.02 | 0.001 | |

| Follow-up | ACT without exercise | DBT with exercise | 28.75 | 10.02 | 0.001 |

| ACT without exercise | Control | 50.08 | 10.02 | 0.001 |

Pairwise Comparisons of Chronic Pain in the Intervention Groups in the Post-intervention and Follow-up Phases

| Groups | Variables | Index | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Squares | F | Sig. | Effect Size | Test Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT and DBT with exercise | Intragroup changes | Time | 214.67 | 1 | 214.67 | 9.22 | 0.004 | 0.18 | 0.84 |

| Group-time | 9229.62 | 2 | 4614.81 | 198.34 | 0.001 | 0.90 | 1 | ||

| Error | 977.20 | 42 | 23.26 | ||||||

| Intergroup changes | Group | 10007.65 | 2 | 5003.83 | 18.90 | 0.001 | 0.47 | 1 | |

| Error | 11114.08 | 42 | 246.62 | ||||||

| ACT and DBT without exercise | Intragroup changes | Time | 306.17 | 1 | 306.17 | 13.49 | 0.001 | 0.24 | 0.95 |

| Group-time | 3765.95 | 2 | 1882.97 | 85.78 | 0.001 | 0.80 | 1 | ||

| Error | 921.86 | 42 | 21.94 | ||||||

| Intergroup changes | Group | 2665.88 | 2 | 1332.94 | 5.10 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.79 | |

| Error | 10957.64 | 42 | 260.89 |

ANOVA Results for the Desire for Treatment in the Intervention Groups

| Stage | Base Group | Compared Group | Mean Difference | Standard Error | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-intervention | ACT with exercise | ACT without exercise | 5.26 | 3.66 | 0.1 |

| ACT with exercise | DBT with exercise | 9 | 3.66 | 0.1 | |

| ACT with exercise | DBT without exercise | 10.73 | 3.66 | 0.04 | |

| ACT with exercise | Control | 34.66 | 3.66 | 0.000 | |

| ACT without exercise | DBT with exercise | 3.73 | 3.66 | 1 | |

| ACT without exercise | DBT without exercise | 5.46 | 3.66 | 1 | |

| ACT without exercise | Control | 29.40 | 3.66 | 0.000 | |

| DBT with exercise | DBT without exercise | 1.73 | 3.66 | 1 | |

| DBT with exercise | Control | -25.66 | 3.66 | 0.000 | |

| DBT without exercise | Control | -23.93 | 3.66 | 0.000 | |

| Follow-up | ACT with exercise | ACT without exercise | 5.93 | 3.74 | 1 |

| ACT with exercise | DBT with exercise | 9.40 | 3.74 | 0.14 | |

| ACT with exercise | DBT without exercise | 11.60 | 3.74 | 0.02 | |

| ACT with exercise | Control | -36.73 | 3.74 | 0.000 | |

| ACT without exercise | DBT with exercise | 3.46 | 3.74 | 1 | |

| ACT without exercise | DBT without exercise | 5.66 | 3.74 | 1 | |

| ACT without exercise | Control | -30.80 | 3.74 | 0.000 | |

| DBT with exercise | DBT without exercise | 2.20 | 3.74 | 1 | |

| DBT without exercise | Control | -25.13 | 3.74 | 0.000 |

Bonferroni’s Post-hoc Test for the Desire for Treatment in the Control and Intervention Groups

| Stage | Base group | Compared Group | Mean Difference | Standard Error | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-intervention | ACT with exercise | DBT with exercise | -18.60 | 6.89 | 0.03 |

| ACT with exercise | Control | 21.46 | 6.89 | 0.01 | |

| DBT with exercise | Control | 12.25 | 6.89 | 0.04 | |

| Follow-up | ACT with exercise | DBT with exercise | -13.86 | 6.89 | 0.001 |

| ACT with exercise | Control | 21.46 | 6.89 | 0.01 | |

| DBT with exercise | Control | 15.25 | 6.89 | 0.04 | |

| Post-intervention | ACT without exercise | DBT without exercise | 15.40 | 5.06 | 0.01 |

| ACT without exercise | Control | -29.84 | 5.06 | 0.001 | |

| DBT without exercise | Control | -14.44 | 5.06 | 0.02 | |

| Follow-up | ACT without exercise | DBT with exercise | 15.40 | 5.06 | 0.01 |

| ACT without exercise | Control | -29.84 | 5.06 | 0.001 | |

| DBT without exercise | Control | -14.44 | 5.06 | 0.02 |

Pairwise Comparisons of the Desire for Treatment in the Intervention Groups in the Post-intervention and Follow-up Phases

5. Discussion

The current study investigated the impact of ACT and DBT-based interventions, with and without exercise, on pain outcomes and the desire for treatment in substance-dependent men with chronic pain. Participants in both the control and intervention groups showed no statistically significant differences in demographic characteristics. Additionally, pre-intervention scores for pain outcomes and the desire for treatment did not differ significantly between intervention and control groups. However, following the interventions, participants in the intervention groups exhibited significantly higher scores compared to those in the control group. Overall, the results underscored the significant effectiveness of ACT and DBT-based interventions in managing pain outcomes and enhancing the desire for treatment. Furthermore, scores for these variables during the post-intervention and follow-up phases significantly differed from pre-intervention scores and those of the control group across intervention and follow-up stages.

While distress tolerance in DBT refers to short-term interventions, emotion regulation in the same approach pertains to long-term lifestyle changes promoting healthier emotional states (35). The findings of this study suggested that following intervention completion, DBT (with and without exercise) had a notable effect on improving chronic pain outcomes. This aligns with previous research demonstrating DBT's efficacy in enhancing sleep quality and pain management among patients with multiple sclerosis (44) and addressing emotional regulation changes due to pain in individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD) (45).

Moreover, numerous studies have affirmed ACT's significant effectiveness compared to other treatments in improving chronic pain outcomes (46). A meta-analysis also provided ample evidence supporting ACT's efficacy in treating chronic pain and managing its outcomes (47). Acceptance and commitment therapy-based interventions have shown promise in reducing pain intensity in individuals with epilepsy (48) and ameliorating anxiety and depression in those with chronic pain (49). While some studies have reported ACT-based interventions' efficacy in enhancing treatment adherence among individuals with substance abuse (50) issues, there is limited research on the effectiveness of ACT combined with exercise on chronic pain in individuals with drug addiction.

Data from our study indicated that ACT, alongside aerobic exercise, significantly and effectively improved pain outcome scores among drug-dependent individuals, with this improvement sustained post-intervention and during the follow-up phase. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and DBT-based interventions enhance individuals' flexibility in confronting behavioral consequences in the present and enable them to live in alignment with their values (51). ACT-based interventions encourage clients to distance themselves from their "conceptualized self" and explore the "self as context," enabling them to reevaluate problems from past experiences and existing knowledge, thus aiding individuals with chronic pain in coping with their condition (52).

The improvement in pain outcomes is expected to influence the desire for addiction treatment and control relapse. Craving for drugs can be induced by active non-acceptance of pain in drug-dependent patients (53). Increasing adherence and desire for treatment are behaviors associated with the disease that predict successful treatment or reduce its severity (54). Research findings have confirmed non-adherence to treatment to vary from 15 to 93% (55). Psychological training and psychotherapy focused on adherence have been shown to be effective in improving treatment adherence (56). A meta-analysis of more than 70 studies found that behavioral and multicomponent interventions are effective in promoting treatment adherence among youth with chronic illnesses (54). Since emotions and behaviors can influence the treatment process, ACT and DBT interventions, along with exercises, help control chronic pain and prevent recurrence by affecting the regulation of emotions. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and DBT-based interventions are a new generation of cognitive behavioral therapies that increase psychological flexibility in people (57). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, as an approach, focuses on behavior (58), while DBT focuses on emotion regulation, greatly contributing to improving the desire for treatment (59). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy focuses on strategies based on awareness and acceptance along with commitment and behavior change strategies to increase psychological flexibility, and DBT seeks to help improve people's performance through mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotion regulation, and effective interpersonal relationships (57). It has also been shown that physical activity and exercise, such as aerobics, help in pain management by increasing the level of mood-enhancing chemicals, stimulating the pleasure/reward circuits, reducing the degree of pain perception, improving the quality of life, and controlling the anxiety caused by pain (60).

The present study showed that DBT is effective in controlling relapse by improving the desire for treatment and promoting treatment adherence (59, 61). Likewise, a study of 48 people who visited a psychosocial health center indicated that DBT skills may be a useful mechanism for reducing people's desire to use alcohol and other substances (61). Another study examined a 3-month dialectical behavioral therapy skills training (DBT-ST) program for the treatment of alcohol use disorder (AUD) and concurrent substance use disorders (CO-SUDs) and found significant and moderate to large improvements in the number of consecutive days of abstinence (CDA), alcohol use disorder (AUD), concurrent substance use (CO-SUDs), and difficulties in emotion regulation (DER) (62). However, ACT intervention with exercise had the greatest effect on the desire for treatment and was significantly effective in desire for treatment and relapse control compared to DBT and control groups. Although no study has addressed the combined effectiveness of ACT and exercise in the treatment of addiction, our findings were consistent with some aspects of previous studies (58, 63). Previous studies have confirmed the effectiveness of ACT in inpatients (n = 85) and outpatients (n = 85) (58). Besides, in recent years, ACT has been reported as a promising and empirically supported approach for the treatment of addiction (63).

5.1. Conclusions

The success of treatment and prevention of relapse, as a basic strategy for addiction treatment, requires the adoption of strategies that help empower addicted patients. Thus, controlling the consequences of chronic pain, as one of the factors that trigger and perpetuate addiction, and improving the desire for and adherence to treatment using ACT protocols combined with exercise are among the effective strategies that can aid the addiction treatment process.