1. Background

Children's cancer encompasses a group of malignancies that are more diverse than cancers in adults and is the most common cause of death among children aged 1 to 16 years in Western countries (1). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the number of new cancer cases is estimated to rise to 26 million globally by 2040, leading to an increased global burden of cancer (2), with cancer remaining the third leading cause of death worldwide (3). Additionally, cancer accounts for approximately 4% of deaths in children under 5 years of age and 13% of deaths in children aged 5 to 15 years in the Iranian population (4). The substantial costs of treatment, the desire for earlier discharge (5), and the chronic and debilitating nature of cancer have resulted in a shift toward providing care at home for patients (6).

Caring for cancer patients differs from caring for other chronic patients due to the unpredictable nature of this disease and its progressive course (7). Since caregivers spend most of their time with the patient, they often neglect their own needs, leading to changes in their lives, including the burden of caregiving (8). The caregiving burden refers to the amount of stress experienced by the individual responsible for caring for the patient (9). The term "burden" has both subjective and objective dimensions (10). Subjective burden encompasses caregivers' personal feelings and arises during the act of caregiving, while objective burden is defined as events or activities associated with negative caregiving experiences (11).

The caregiving burden adversely affects caregivers in various ways. Psychologically, caregivers are at risk of stress, anxiety, and depression (12). Physically, conditions such as high blood pressure, heart problems, arthritis, and back pain are common among caregivers (5). Socially, caregivers often experience changes in their roles, decreased effectiveness in fulfilling their roles, and alterations to their job and life plans (13). Abbasnezhad et al. demonstrated a high prevalence of financial problems, anxiety, depression, and low quality of life among family caregivers of cancer patients (5).

If the psychological burden of caregivers remains untreated, it can lead to physical and mental health problems for the caregivers themselves (14). Current therapeutic approaches, including quality-of-life therapy (QOLT), should focus on improving and changing quality of life, expanding capabilities, and fostering life satisfaction (15). Quality-of-life therapy is a new and comprehensive approach based on the principles of positive psychology (16) and emphasizes mental health within the context of daily life (17). This approach incorporates mindfulness, acceptance, and flexibility to enhance well-being and quality of life while prioritizing the cultivation of positive emotions (18).

Quality-of-life therapy was developed by Frisch in 2006 from a combination of Aaron Beck's (1960) psychological approach in the clinical domain, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s Activity Theory (1997), and Seligman's (2002) positive psychology. This therapy aims to facilitate cognitive behavioral change across five main domains: Living conditions, subjective attitudes and perceptions, satisfaction criteria, satisfaction with a specific area of life, and overall satisfaction with life (19). These five factors are collectively known as the CASIO model, which was developed based on the perspectives of Kimweli and Stilwell (20).

The QOLT approach encourages individuals to view their psychological well-being as a crucial aspect of mental health and to understand that mental health is not merely the absence of mental illness; rather, individuals should always strive to enhance their life satisfaction (17). The goal of QOLT is to promote self-care, prevent burnout, and bridge the gap between what a person desires and their current situation. This approach fosters satisfaction by examining key areas of life, including physical health, self-esteem, goals and values, work, finances, leisure, learning, creativity, helping others, love, friendships, children, relatives, home and neighbors, community, and partners (21). Previous studies have indicated that the positive effects of QOLT persist for months after the interventions (22) and that it is more effective than traditional supportive therapy interventions (23).

Karimi et al. examined the impact of QOLT counseling on the stress and life satisfaction of 80 family caregivers of individuals with addictions in Zahedan. The findings suggested that QOLT effectively reduces the stress and psychological burden experienced by caregivers of patients with chronic and severe diseases while enhancing the life satisfaction of this vulnerable group (24). Additionally, Abedi and Vostanis evaluated the effects of QOLT on parents of children with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in Iran. This study aimed to assess the short-term impact of QOLT interventions on enhancing the capabilities of families with 40 children and their mothers. The findings indicated that QOLT was associated with a reduction in the severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms and anxiety, as well as an increase in children's satisfaction. Furthermore, the QOLT intervention led to a significant improvement in the quality of life for mothers in the intervention group compared to the control group. The authors concluded that QOLT, similar to cognitive behavioral therapy, can effectively address issues related to patients' families (25).

Given the advances in the diagnosis and treatment of children's cancers, the life expectancy of these children has increased significantly. Consequently, parents spend a considerable amount of time involved in the treatment and care processes, and with the aid of scientific advancements, they have a greater chance of living alongside their children. Caring for a child with a life-threatening disease such as cancer presents serious emotional, physical, social, spiritual, and economic challenges for families and parents. As parents are one of the primary sources of emotional support and care for children with cancer, providing effective psychological support to them can facilitate sound and prompt decision-making while maintaining and improving their physical and psychological health in coping with their child's illness, thereby enabling them to provide more psychological support.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to examine the impact of the QOLT program on the psychological burden of mothers of children with cancer.

3. Methods

This quasi-experimental study, with a pre-test-post-test design, was conducted on mothers of children with cancer who visited the chemotherapy departments of Ali Ibn Abi Talib Hospital in Zahedan in 2023. The inclusion criteria for mothers were willingness to participate in the study, ability to communicate, being at least 20 years old, possessing minimum literacy, absence of diagnosed or known mental disorders, and no experience of recent life crises except for the child’s cancer. The exclusion criteria included absence or non-participation in more than one training session, occurrence of trauma and crisis during the study, and severity or criticality of the child's illness during the study that could affect the mother's psychological state. Additionally, the inclusion criteria for the children were having leukemia, being aged 12 years or younger, receiving at least one course of chemotherapy, absence of metastasis according to the patient's medical records, and living with both parents.

Following a similar study, the sample size was estimated to be 34 individuals per group using the following formula, with an 80% confidence interval and 95% test power (24). However, considering the potential for participant dropout, the sample size was adjusted to 40 individuals per group (80 individuals in total).

z1-α/2 = 1.96, z1-β = 0.85, S1 = 4.36, S2 = 4.93, X1 = 11.50, X2 = 14.67

The instruments used to collect data in this study included a demographic information questionnaire that assessed the child’s age and sex, the mother’s age, education, and occupation, the duration and grade of the disease, and the number of children in the family, as well as the 22-item Zarit Burden interview (ZBI). This interview is the most frequently used tool for measuring the perceived psychological burden experienced by family caregivers. The instrument contains 22 items that measure four dimensions of psychological burden, including personal, social, emotional, and economic burdens on the patient's caregiver. Each item is answered as never (0), rarely (1), sometimes (2), often (3), and always (4). The total score obtained by caregivers ranges from 0 to 88. The reliability of the original version of the instrument was confirmed by its developer, with a test-retest value of 0.71, and its internal consistency was confirmed with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.91 (26). The instrument was translated by Navidian and Bahari for use in Iran, and its reliability was confirmed with a test-retest value of 0.94. In addition to its content validity, the validity of the instrument was confirmed with a strong positive correlation with the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (r = +0.89) and the Beck Depression inventory (BDI) (r = +0.67) (27). The reliability of this tool in the present study was confirmed with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.92.

After receiving permission from the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, the researcher went to Ali Ibn Abi Talib Hospital in Zahedan and made the necessary arrangements with the hospital officials to conduct the study. After identifying children with cancer in the chemotherapy department, the mothers who met the inclusion criteria were selected as participants through convenience sampling. The researcher provided information about the objectives of the study, the safety of the intervention, the confidentiality of the participants’ data, and their freedom to withdraw from the study at any stage. Informed consent was then obtained from the participants.

Subsequently, the participants were divided into intervention and control groups using a random allocation method. To do this, a total of 80 colored cards representing group membership (red for the intervention group and white for the control group) were prepared. Each participant was assigned to either the intervention or control group by randomly drawing a card. The Zarit Burden Interview was completed as a pre-test by the participants in both groups. After making the required arrangements, the participants in the intervention group attended eight QOLT training sessions in small groups of 4 to 6 people every other day (three sessions per week). Each session lasted 60 to 90 minutes. The intervention sessions were held in a room in the hospital by a senior psychiatric nursing expert with clinical experience, under the supervision of a subject-matter expert with a Ph.D. in counseling. Eight weeks after the completion of the intervention, the items in the Zarit Burden Interview were completed again as a post-test by the participants in both groups. The content of the QOLT intervention has been used and confirmed in several studies in Iran. To comply with ethical protocols, the content of the educational booklet was also provided to the participants in the control group. Table 1 shows the content of the intervention program.

| Sessions | Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Introducing group members, defining the role of quality of life in a person's life, presenting quality-of-life therapy and new treatment approaches in psychology, outlining the content of the therapy sessions, reaching an agreement on the important areas from the 16 identified in the quality-of-life therapy, and examining the role of relevant variables in people's mental health while receiving feedback from group members. |

| 2 | Reviewing the content of the previous session, introducing the CASIO model, starting with the C domain as the first strategy and its application in enhancing people's quality of life. |

| 3 | Reviewing the content of the previous session, discussing the CASIO model, and introducing the A domain as the second strategy along with its application in improving people's quality of life. |

| 4 | Reviewing the content of the previous session, discussing the CASIO model, introducing the SIO domains as the third, fourth, and fifth strategies for improving life satisfaction, and teaching the principles of quality-of-life therapy. |

| 5 | Reviewing the content of the previous session, discussing the principles of quality-of-life therapy and their applications for improving life satisfaction. |

| 6 | Reviewing the content of the previous session, discussing the principles of quality-of-life therapy, their relationships, and applications in everyday life. |

| 7 | Generalizing the principles of CASIO to different life situations, applying the principles of quality-of-life therapy, and administering the post-test. |

| 8 | Reviewing the CASIO model and assignments, recapping the content of previous sessions, discussing the self-administered quality-of-life therapy exercise, and additional assignments. |

3.1. Ethical Considerations

The protocol for this study was approved under the code of ethics IR.ZAUMS.REC.1402.369 by the ethics committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences. Informed consent was obtained from the participants, who were assured of the confidentiality of their information and their right to withdraw from the study at any stage if they wished.

3.2. Data Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS 27 software with both descriptive and inferential statistics. The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Initially, the data were summarized using descriptive statistics, which included mean, standard deviation, frequency, percentage, minimum, and maximum values. The mean scores of the two groups were compared using the independent samples t-test, while the mean scores within each group were compared using the paired samples t-test. Additionally, the frequency of the research variables was examined using the chi-square test. The analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention program while controlling for the influence of the pre-test and other variables that differed significantly between the two groups (maternal age, number of children, and duration of illness). All statistical procedures were performed at a significance level of less than 0.05 (P < 0.05).

4. Results

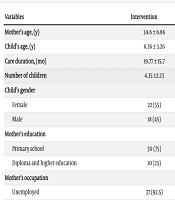

No participants from either the intervention or control groups withdrew from the study, resulting in a total of 80 participants being analyzed. An assessment of the participants’ demographic characteristics (Table 2) indicated that the mean age of the mothers in the intervention and control groups was 34.60 ± 6.86 and 31.23 ± 6.08 years, respectively, revealing a significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.02). Additionally, the average number of children for mothers in the intervention group (4.35 ± 2.23) was significantly higher than that of the control group (2.88 ± 1.36) (P = 0.001). The duration of the disease in the intervention group (19.77 ± 15.7) was also significantly longer compared to the control group (11.28 ± 11.42) (P = 0.007). As shown in Table 2, no significant differences were found between the two groups regarding other demographic variables, such as children's age, mothers' occupational and educational status, and children's gender (P < 0.05).

| Variables | Intervention | Control | P-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age, (y) | 34.6 ± 6.86 | 31.23 ± 6.08 | 0.02 |

| Child’s age, (y) | 6.36 ± 3.26 | 5.93 ± 3.44 | 0.57 |

| Care duration, (mo) | 19.77 ± 15.7 | 11.28 ± 11.42 | 0.0078 |

| Number of children | 4.35 ±2.23 | 2.88 ± 1.36 | 0.001 |

| Child’s gender | 0.82 | ||

| Female | 22 (55) | 23 (57.5) | |

| Male | 18 (45) | 17 (42.5) | |

| Mother’s education | 0.061 | ||

| Primary school | 30 (75) | 22 (55) | |

| Diploma and higher education | 10 (25) | 18 (45) | |

| Mother’s occupation | 0.99 c | ||

| Unemployed | 37 (92.5) | 36 (90) | |

| Employed | 3 (7.5) | 4 (10) |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

b Independent samples t-test.

c Fisher’s exact test.

The data presented in Table 3 indicate that the mean score of psychological burden experienced by mothers in the intervention group decreased significantly from 36.95 ± 12.21 to 27.22 ± 12.82 (P = 0.0001), while it increased significantly in the control group from 37.02 ± 11.11 to 41.20 ± 11.50 (P = 0.001). The independent samples t-test results revealed that the mean score of psychological burden experienced by mothers in both groups did not differ significantly before the implementation of the QOLT training program (P = 0.97); however, this difference became significant after the completion of the intervention (P = 0.0001). After confirming the necessary assumptions, the results of the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) (Table 4), controlling for the effects of the pre-test scores, mothers' age, number of children in the family, and duration of the disease, indicated that the mean score of psychological burden for mothers of children with cancer in the two groups was significantly different following the QOLT intervention (P = 0.0001).

| Group | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | Mean Difference | Paired Samples t-Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 36.95 ± 12.21 | 27.22 ± 12.82 | 9.72 ± 7.79 | 0.0001 |

| Control | 37.02 ± 11.11 | 41.20 ± 11.50 | 4.17 ± 7.34 | 0.001 |

| Independent samples t-test | 0.97 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

| Source of Changes | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Squares | F | Sig. | Effect Size | Test Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | 6958.56 | 1 | 6958.56 | 127.61 | 0.0001 | 0.63 | 1 |

| Maternal age | 78.10 | 1 | 78.10 | 1.43 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.21 |

| Number of children | 4.24 | 1 | 4.24 | 0.07 | 0.78 | 0.001 | 0.59 |

| Duration of illness | 180.61 | 1 | 180.61 | 3.41 | 0.068 | 0.04 | 0.44 |

| Group | 3096.68 | 1 | 3096.68 | 56.79 | 0.0001 | 0.43 | 1 |

| Error | 4089.45 | 75 | 54.52 | ||||

| Total | 109123 | 80 |

5. Discussion

This study investigated the effect of the QOLT intervention on the psychological burden of mothers of children with cancer. The findings indicated that the intensity of the psychological burden for the mothers in the intervention group was significantly reduced compared to the control group after the implementation of the intervention, demonstrating the positive effect of QOLT on alleviating the psychological burden of mothers of children with leukemia. In line with these findings, Karimi et al. reported that QOLT training and counseling reduce the stress and psychological burden of caregivers for patients with chronic and severe diseases and improve the life satisfaction of this vulnerable group (24).

The QOLT approach is a form of meaning therapy that helps caregivers identify the most meaningful aspects of life that are effective and beneficial for their health at the moment. Accordingly, Hughes showed that individuals who find meaning in challenging and stressful situations typically experience lower levels of negative emotions and stress (28). Since spirituality is an important component of QOLT, enhancing spirituality in individuals contributes to improved mental health and reduced stress. Kajbaf and Hoseini evaluated the effectiveness of QOLT and spiritual therapy in patients with tension headaches and concluded that both interventions significantly impact stress tolerance in patients during the post-intervention and follow-up phases (29).

Quality-of-life therapy, which combines the cognitive approach with activity theory, aims to teach caregivers that coping with unpleasant situations involves reducing stressors, thereby assisting them in managing their circumstances and effectively utilizing opportunities. These abilities and skills enable family caregivers to control and respond to challenges when faced with stressful situations by considering all aspects. Therefore, active participation in mastering the surrounding environment is regarded as a vital element of positive psychological action, indicating effective coping with stress (30).

The present study also demonstrated that QOLT has a positive and significant effect on the effective reduction of psychological burden. Similarly, Navidian et al. found that group interventions aimed at reducing psychological burden were effective in a sample of home caregivers of patients, and this type of intervention can indirectly improve the quality of life for both patients and caregivers (31). Moreover, Magliano et al. stated that combining family psychological training interventions with routine mental healthcare significantly reduces the psychological burden on family caregivers (32).

A clinical trial by Araghian et al. compared the effects of QOLT and compassion-based therapy on the quality of interpersonal relationships and distress tolerance in women facing marital conflicts. The findings suggested that both interventions positively impacted family mental health, including psychological distress tolerance and interpersonal relationship quality. However, QOLT was found to have a greater effect on the quality of interpersonal relationships compared to compassion-based therapy (33).

Intervention programs similar to the one conducted in this study for other chronic diseases, such as mental disorders, cancer, and diabetes, have shown reductions in caregiver burden and improvements in caregivers' quality of life. Etemadifar et al. noted that group support for caregivers of heart patients not only reduces care burden but also enhances the ability and self-confidence of family members to provide care at home (34). Additionally, Navidian et al. suggested that empowering family members as a group can improve patient care quality and enhance their physical and mental health, in addition to reducing caregiver burden (35).

Psychological interventions have proven effective for caregivers of patients with physical conditions, including those admitted to intensive care units, patients with autism, and patients with OCD (25, 35), as well as for individuals without any diseases (36). Toghyani et al. demonstrated that QOLT interventions improve positive emotions, well-being, and quality of life in students and adolescents (37).

Overall, it can be argued that QOLT training can improve psychological burden in individuals by encouraging frequent practice. Symptoms of psychological burden include feelings of rejection, anger, hatred, impatience, worthlessness, and trouble. Accordingly, QOLT focuses on examining individuals' schemas and cognitive errors, aiming to change attitudes and correct irrational beliefs and cognitive distortions. Thus, it reduces conflicts and significantly impacts relationships. This suggests that individuals can cope with their issues and problems by changing their attitudes and adopting a structured approach. The goal of QOLT is to increase skills and knowledge, allowing clients to reinforce their resolve regarding aspects of satisfaction that can be changed. Consequently, they achieve greater happiness and success. This approach aims to help clients identify, pursue, and fulfill their needs, goals, and aspirations in valuable areas of life.

Individuals equipped with a set of skills and capabilities are more successful in facing problems because the use of effective coping responses helps them overcome physical and mental challenges, enhance interpersonal and social relationships, and resolve conflicts. As a result, these individuals experience an improved quality of life and mental health.

The data in the present study also indicated that the mean score of psychological burden for the mothers of children with cancer in the control group significantly increased in the post-intervention phase compared to the pre-intervention phase. This finding can be attributed to the relatively long time interval between the pre-test and post-test, which lasted nearly two months, leading to an increase in psychological burden for the mothers in the control group. During this period, the mothers received no supportive interventions. Additionally, the prolonged chemotherapy process, frequent hospital visits, and increased stress associated with caring for a child with cancer contributed to the significant rise in psychological burden experienced by the participants.

The development and implementation of an 8-session psychological intervention aimed at the psychological well-being of mothers, in contrast to intensive and short-term training focused on cancer-related issues, may be considered one of the strengths of the present study. Some limitations of this study included the diversity of cancer types, the relatively small sample size in each group, and the ethnic and religious beliefs surrounding the concept of disease and cancer, which restricted the generalizability of the findings. Thus, future studies should focus on patients with different types of cancers in various socio-cultural contexts and include a larger sample size. Further research can also examine patients’ life satisfaction by conducting online intervention sessions.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of the present study indicate that the QOLT intervention has a positive and significant effect on reducing the psychological burden of mothers of children with cancer. The techniques and methods used in this intervention, including psychological training, teach mothers about the goals, values, and principles related to satisfaction that foster happiness. Given the broad range of applications of this therapy, especially for non-patients experiencing stress and psychological burden, the QOLT intervention for mothers of children with cancer, combined with advanced treatments for their children, can be utilized by medical staff, particularly nurses. Reducing the psychological burden and enhancing the mental health of mothers will undoubtedly help improve the quality of care for children with cancer.