1. Introduction

Cryoglobulinemia is described by the presence of serum cryoglobulins, which are atypical proteins (mostly immunoglobulins) soluble at 37°C and precipitating at lower temperatures. Type II mixed cryoglobulinemia (MC) is a rare disease of unknown etiology, characterized by a blend of polyclonal immunoglobulin G (IgG) in association with a monoclonal Ig, typically IgM or IgA.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections are involved in approximately 90% of MC cases (1), whereas there is no indication of current or previous exposure to HCV (serum antibodies) in 10% of cases, which are generally associated with a severe course of and suboptimal responses to conventional therapies (2). In some cases, connective tissue diseases (primarily systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren’s syndrome, and systemic sclerosis) and lymphoproliferative disorders (B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma in most cases) (2) are found in an additional 5% of MC cases. Furthermore, cryoglobulinemia without an associated disease is defined essential (EMC) and accounts for 5% of cases.

We managed a rare case of HCV-negative cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis (CG), which developed in correspondence with the recurrence of prostate adenocarcinoma. We also present a comprehensive review of the literature on paraneoplastic MC.

2. Case Presentation

A 79-year-old Caucasian man was admitted to the department of nephrology in July 2016 because of the onset of a nonpalpable purpura at the limbs and abdomen 2 days earlier, without pruritus but with diarrhea and peripheral edema. The patient had been successfully treated in 2007 with intensity-modulated radiation therapy for localized prostate adenocarcinoma. He was regularly followed-up until the beginning of July 2016 when cancer recurrence was diagnosed and radiation therapy was reinitiated. The patient was obese and used olmesartan (80 mg) daily for hypertension and stable mild chronic kidney disease (last serum creatinine level, 1.4 mg/dL in July 2016).

Blood tests performed on admission showed acute renal failure (creatinine, 5.9 mg/dL; blood urea nitrogen [BUN], 250 mg/dL; potassium, 6.5 mEq/L), associated with oliguria and acute inflammation. Additional blood and urine tests (Table 1) indicated positive cryoglobulins and cryocrit of 20% with a substantial amount of urinary proteins. The serum examinations were compatible with a nephritic syndrome, secondary to HCV-negative MC. Cryoprecipitate was analyzed via immunodiffusion and immunofixation electrophoresis to identify the cryoglobulin type. The results showed monoclonal IgM and polyclonal IgG, thus confirming the presence of type II cryoglobulinemia.

| Blood Tests | Normal Values | |

|---|---|---|

| Leukocytes, 103/mm3 | 4.48 | 4.0 - 10.0 |

| Hemoglobin level, g/dL | 9.4 | 13.0 - 18.0 |

| Platelet count, 103/mm3 | 234 | 130 - 400 |

| Sodium level, mEq/L | 148 | 135 - 145 |

| Potassium level, mEq/L | 6.5 | 3.5 - 5.1 |

| Creatinine level, mEq/L | 5.9 | 0.8 - 1.2 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (BUN), mEq/L | 250 | 20 - 40 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, IU/L | 269 | 125 - 243 |

| Rheumatoid factor, UI/mL | 23 | 0 - 30 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 15 | 10 - 30 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 20 | 10 - 30 |

| C3, mg/dL | 164 | 85 - 190 |

| C4, mg/dL | 7 | 10 - 65 |

| IgA, U/L | 362 | 40 - 350 |

| IgG, U/L | 784 | 840 - 1660 |

| IgM, U/L | 87 | 50 - 300 |

| Prostate-specific antigen, ng/mL | 4.19 | 0 - 4.0 |

| HbsAg | Negative | Negative |

| HCV antibody | Negative | Negative |

| HCV RNA | Negative | Negative (real-time PCR) |

| Cryoglobulins | Positive | Negative |

| Cryocrit, % | 20 | Negative |

| Antinuclear anibody | 1:320 | < 1:4 |

| Anti-dsDNA antibody | Negative | < 1:10 |

| Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies | Negative | Negative |

| Albumin level, g/dL | 2.6 | 3.5 - 4.5 |

| Proteinuria, g/24h | 5.7 | 0.005 - 0.015 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 16.93 | 0.1 - 1 |

| α1-globulins, % | 8.4 | 2.9 - 4.9 |

| α2-globulins, % | 16.6 | 7.8 - 11.8 |

The abdominal ultrasound demonstrated the regular size of both kidneys and hyperechogenicity of the renal cortex with a 3-cm cyst on the lower pole of the left kidney. The chest X-ray ruled out pleural effusion, and arterial blood gas examination showed no respiratory or metabolic alterations. Intravenous furosemide was initiated to achieve a urinary output of nearly 1500 cc/day, while renal function test results did not improve. The renal biopsy was performed after 4 days.

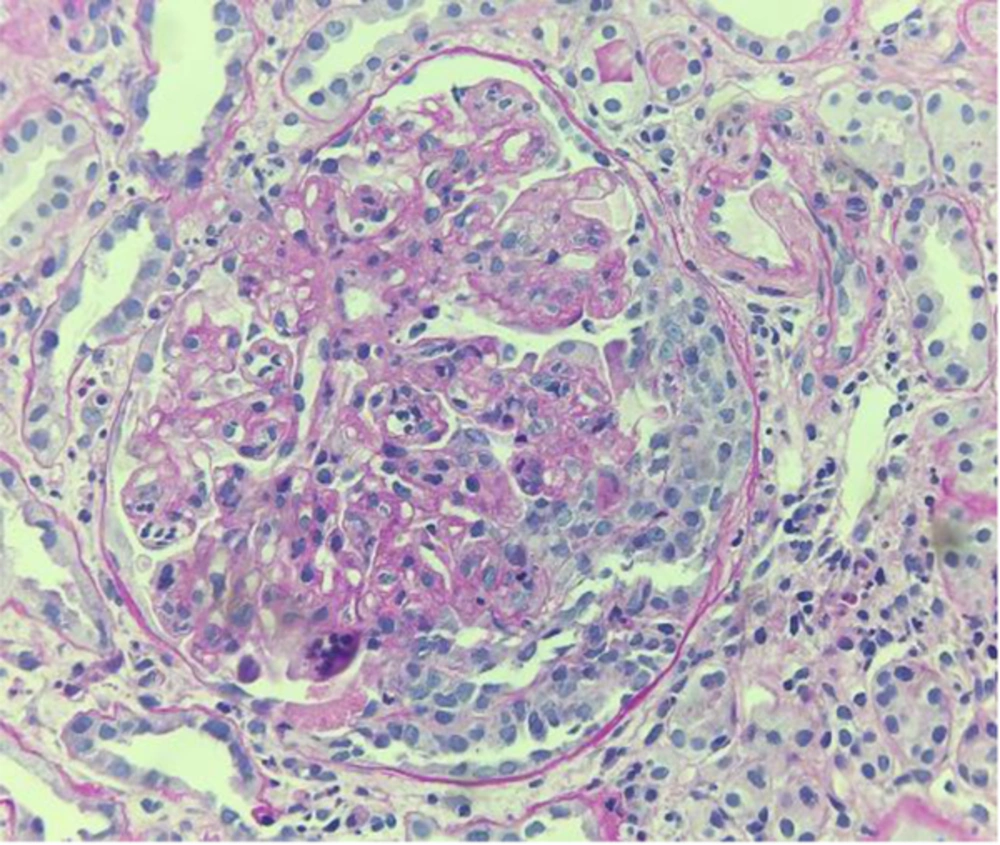

Because of the patient’s severe obesity and poor compliance, a tissue sample suitable for light microscopy was collected, although it was insufficient for immunofluorescence and electron microscopy. Nonetheless, light microscopy revealed a membranoproliferative disease with infiltration of monocytes and capillary duplication with a globular pattern; mesangial proliferation and occasional extracapillary florid proliferation were also observed (Figure 1).

Due to the recent development of prostate cancer in the patient, cyclophosphamide was contraindicated despite its established use for severe CG (3). Therefore, intravenous administration of methylprednisolone (500 mg/pulse) was applied for 3 days, followed by prednisolone (1 mg/kg) daily. After 3 days, the purpura became less evident and disseminated, while renal function failed to recover (serum creatinine, 5.4 mg/dL; azotemia, 210 mg/dL after 10 days). Inevitably, hemodialysis treatment was initiated, using a temporary central venous catheter in the internal jugular vessel. The patient is currently on hemodialysis with a permanent central venous catheter, and his renal function has not shown any improvements despite high-dose steroids and diuretics.

3. Discussion

The majority of CG cases were considered essential until 1993, when Johnson and colleagues reported that cryopositive membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) is associated with chronic HCV infection (4). Today, HCV infection is the cause of nearly 90% of these cases, while the contribution of genetic and environmental factors remains controversial. Approximately 10% of MC cases manifest no evidence of current or previous HCV infection, and 5% have no recognizable associated diseases (1, 2). HCV-negative CG of unknown etiology has been usually reported in areas, such as Northern Europe, where the overall HCV prevalence is almost negligible (5).

In this regard, the French multicenter and transdisciplinary CryoVas survey retrospectively evaluated 242 MC cases without an infectious origin (6) and reported that among secondary MC forms, connective tissue and hematologic diseases were the most frequently identified causes. On the other hand, 117 patients had EMC and were generally older (63 ± 15 vs. 59 ± 15 years), with a more frequent renal involvement (38% vs. 25%), compared to the non-essential forms.

Pertinent to our case, the association between HCV-negative cryoglobulinemia and solid tumors has been rarely reported in the literature (7, 8). Rullier and colleagues provided a single-center inventory of cryoglobulinemia-associated solid cancers in an internal medicine setting (7). The study included 9 patients with HCV-related hepatocellular carcinoma and only 2 HCV-negative cases, chronologically compatible with a paraneoplastic phenomenon; these patients included a woman with treated breast cancer and a man with metastatic bladder and lung cancer with unknown etiology. Furthermore, another case of HCV-negative type II cryoglobulinemia in association with solid cancer was reported in a Caucasian patient (8). In the latter patient, solid cancer was diagnosed as gastric adenocarcinoma, but no other putative risk factors were found (8).

To the best of our knowledge, there is no evidence of an association between HCV-negative CG and solid prostate cancer, as highlighted in the present case. Furthermore, our patient had an atypical and extremely rare presentation of HCV-negative CG with oliguria, associated with the recurrence of prostate adenocarcinoma. Despite evidence on the suboptimal response of HCV-negative EMC to conventional therapies (2, 3, 9), an intravenous steroid treatment was initiated, but it failed to recover renal function and the patient continued hemodialysis.

Considering the reported treatments for HCV-negative cryoglobulinemia, the authors in the French CryoVas survey compared patient responses to corticosteroids alone with rituximab (or alkylating agents) plus corticosteroids in noninfectious mixed cryoglobulinemia (6). The Cox regression model showed that the combination of rituximab with corticosteroids was significantly more effective than corticosteroids alone in achieving a complete clinical response.

In this study, complete response was defined as improvement of all baseline clinical manifestations, including renal function (proteinuria < 0.5 g/day, and/or disappearance of hematuria, and/or improvement of glomerular filtration rate [GFR] > 20% at baseline GFR < 60 ml/min/71.73 m2). On the other hand, combination therapy was significantly associated with severe infections, compared to corticosteroids alone (HR, 9; 95% CI, 3.1-20), especially in patients who received rituximab, along with high doses of corticosteroids (> 50 mg/day). Nevertheless, mortality rate did not differ between the therapeutic regimens (HR, 1.7; 95% CI, 0.5 - 5.8), which may indicate the superiority of combination therapy in HCV-negative CG if compatible with the clinical conditions.

The present case also underlines the importance of detecting CG with a histological pattern of membranoproliferative glomerulopathy, serum cryoglobulin positivity, and features specific to CG on light, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy (10). In light microscopy, typical glomerular lobulation with infiltration of monocytes into the capillary space and large deposits (thrombi) is detected, while immunofluorescence staining for IgM is generally more intense in comparison with IgG in idiopathic MPGN. On the other hand, electron microscopy reveals electron-dense deposits in subendothelial and mesangial regions, which are characterized by thick-walled microtubular or annular structures, measuring 30 nm in diameter.

In the present case, only light microscopy was performed, as the patient’s obesity and limited compliance during the procedure did not allow us to obtain renal tissue samples sufficient for electron microscopy. However, histology was well representative of CG with all its typical features, such as infiltrating leukocytes, membrane basement duplication, and mesangial proliferation. Surprisingly, complement C3 levels may also be normal in MC, as shown in previous reports, possibly due to the acute-phase liver response during infection or inflammation (11-13).

Under the mentioned conditions, the liver is responsible for a large fraction of total complement production, as well as acute-phase proteins. In our case, bioumoral examinations showed an elevated C-reactive protein level of 16.93 mg/dL (normal, 0.1 - 1 mg/dL), serum protein electrophoresis with 8.4% α1-globulins (2.9 - 4.9), and 16.6% α2-globulins (7.1 - 11.8), confirming the acute inflammatory state. CG presents a worse prognosis compared to idiopathic MPGN, regardless of HCV coexistence or other recognizable pathogenic causes (eg, B-cell lymphoma) (9).

In conclusion, the present case suggests the possibility of CG association with solid malignancies, such as prostate adenocarcinoma without evidence of HCV infection. Cryoglobulinemia has been reported in solid tumours, although the pathogenesis remains unclear (14, 15). The stimulus for monoclonal and/or polyclonal cryoglobulin is uncertain and may involve antibodies produced in response to tumour-associated antigens (crossreacting with autologous antigens), antibodies produced by lymphoid elements in cancer, or systemic immunity alterations induced by the tumour in the presence of different antibodies, as illustrated by Lundberg and colleagues. In the present case, cryoglobulins might be attributed to the latter phenomenon, as we also found positive serum antinuclear antibodies, although immunological alterations (eg, an increase in helper T cells or a decrease in suppressor cells) remain to be determined.

Lack of an identifiable putative risk factor, such as HCV, immunological connective diseases, and recurrent prostate cancer, did not allow us to introduce a more comprehensive treatment. Further evidence in the future may bridge the gap and clarify a possible link between solid organ malignances and HCV-negative cryoglobulinemia to determine if it is a paraneoplastic syndrome. In this case, a revised classification of cryoglobulinemia should be encouraged to optimize treatment options.